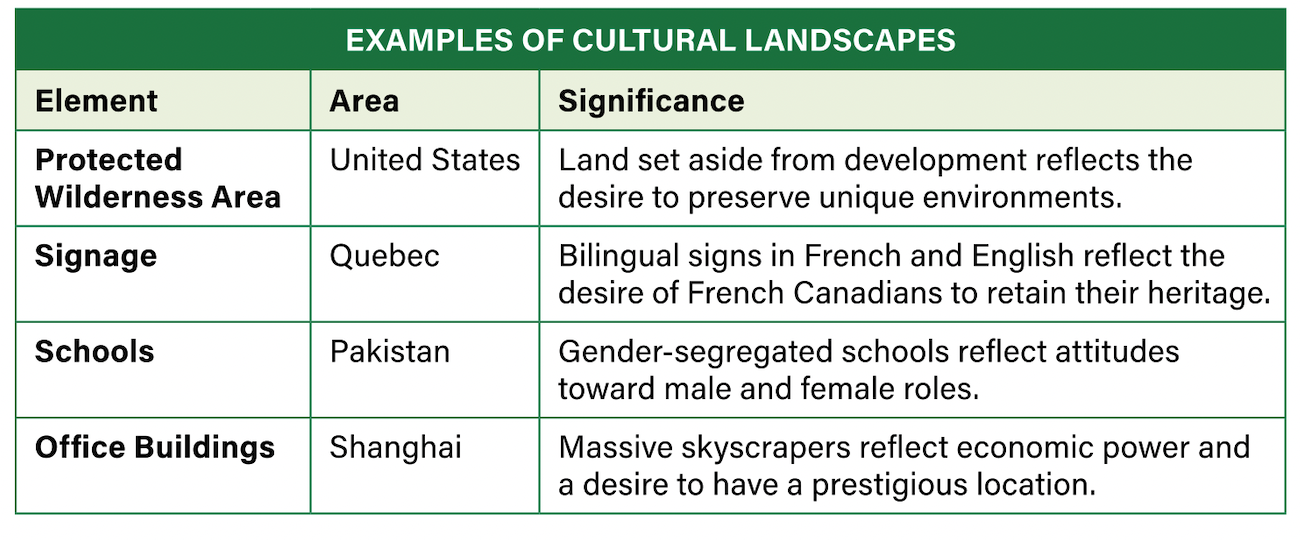

Aspects of Cultural Landscapes

land-use patterns

modern & traditional architecture

religious/linguistic imprints

economic opportunities present

sequent occupancy

gender

Cultural Landscape Concepts

placemaking

sense of place

centripetal forces

centrifugal forces

Across the world, the physical landscape changes with almost immeasurable variability. In the United States, the beaches of Florida, mountains of Colorado, and plains of Oklahoma are only a few of the many landscapes throughout the country. However, condos on the shores in Florida, ski lifts on the slopes in

Colorado, and wheat fields in Oklahoma illustrate the numerous ways humans adjust and adapt to the environment.

While the modern cultural landscape is extremely diverse, it may also exhibit striking similarities from location to location. In the 1986 film Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, the exploits of three teenagers skipping school took place in Chicago, Illinois, and its surrounding suburbs. However, a great deal of the filming took place in California–the suburbs of Long Beach and South Pasadena. Although separated by more than 2,000 miles, the suburbs in Illinois often look remarkably similar to those in California because of comparable incomes, a common American culture, similar architecture, related socioeconomic status, and other related factors. This phenomenon is known as placelessness, in which many modern cultural landscapes exhibit a great deal of homogeneity.

Characteristics of Cultural Landscapes

The boundaries of a region reflect the human imprint on the environment This is called the cultural landscape-the visible reflection of a culture-or the built environment. This concept encompasses any human alteration to the landscape, whether as obvious as a skyscraper or as subtle as a cleared field.

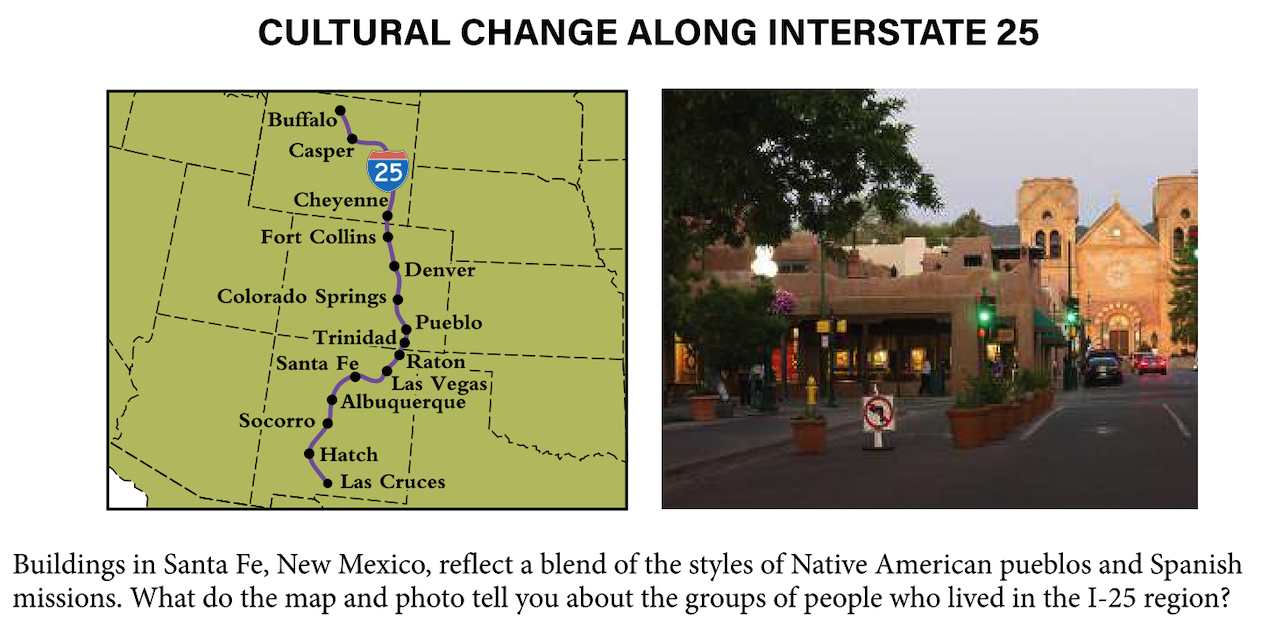

An observant traveler can notice changes in the cultural landscape while driving along a highway. For example, travelers on Interstate 25 going from Wyoming to New Mexico see a definite change, both in toponyms, or place names, and in the built environment. Names change from Anglo words to Spanish names. Wooden buildings are replaced by adobe buildings. Architectural styles shift from looking like those in England to looking like structures in Spain.

The Built Landscape

The word environment is often used in reference to nature. Plants, the air, water, and animals are all part of the natural environment. Human geographers often refer to the built environment, by which they mean the physical artifacts that humans have created and that form part of the landscape. Buildings, roads,

signs, and fences are examples of the built environment.

The architectural style of buildings varies from place to place. Think of typical homes and buildings in China, and then think of homes and buildings in Germany. These differences occur because people with different cultures who live in different physical landscapes construct the buildings, roads, and other elements to create a unique built environment. Anything built by humans is part of the cultural landscape.

Traditional vs. Postmodern Architecture

Traditional architecture style reflects a local cultures history, beliefs, values, and community adaptations to the environment, and typically utilizes locally available materials. Examples would include Spanish adobe (mud) homes common in the southwestern United States or the colonial homes that were wood-constructed with a steep-pitched roof from New England. Many traditional architectural styles have now been adopted by popular culture and are mass produced within many communities, but they are still considered traditional architecture. Traditional architecture is usually built with the utility to people and community as a central focus.

Postmodern architecture developed after the 1960s. It is a movement away from boxy, mostly concrete or brick structures toward high rise structures made from large amounts of steel and glass siding. Most of the skyscapers in the United States today are considered postmodern architectural style. Postmodernism has evolved to also include more use of curves, bright colors, and large glass atriums that bring light into spaces.

During the 21′ century, a new style called contemporary architecture has emerged as an extension of postmodern architecture. This style uses multiple advances to create buildings that rotate, curve, and stretch the limits of size and height. Postmodernism and contemporary downtown skylines reflect businesses and corporations, and the towering height often is considered a reflection of a city’s wealth and power. Both styles of architecture are known for the drama and large-scale beauty of the structures but often are criticized for a lack of an approachable human scale interaction. Both styles can create a steel

and glass canyon feel when viewing from the street level. Postmodern and contemporary architecture are associated with globalized popular culture

Ethnic Enclaves

Ethnicity refers to membership within a group of people who have common experiences and share similar characteristics such as ancestry, language customs, and history. The neighborhood or subregional scale of the cultural landscape might include ethnic enclaves–clusters of people of the same culture-that are often

surrounded by people of the dominant culture in the region. Ethnic enclaves sometimes reflect the desire of people to remain apart from the larger society. Other times, they reflect a dominant cultures desire to segregate a minority culture. Inside these enclaves are often stores and religious institutions that are supported by the ethnic group, signs in their traditional language, and architecture that reflects the group’s place of origin. These enclaves can provide a buffer against discrimination by the dominant culture or a network of people to help with employment and cultural integration. Examples would include “Chinatown” in San Francisco or “Little Mogadishu, a Somali enclave in Minneapolis.

Geography of Gender

The geography of gender has become an increasingly important topic for geographers in recent decades. In folk cultures, people often have clearly defined gender-specific roles. Women usually handle the domestic responsibilities, such as farming, educating children, and caring for family members. Men often

work outside the house earning money and serving as leaders in religion and politics. In popular culture, traditional gender-specific roles are challenged. Women in popular culture tend to have more access to education which leads to more opportunities to work outside of the home. In turn, this gives women more

economic power and opportunities to serve as leaders.

The concept of gendered spaces or gendered landscapes clarifies the importance of cultural values on the distribution of power in societies. Throughout history and in many cultures, certain behaviors have been acceptable for only one gender, and often only in certain spaces. Men have commonly operated more freely than women in public spaces, while certain private spaces have been reserved for women. These differences might appear in the etiquette of visiting someone’s home. The host might welcome men in the

public areas on the main level but feel comfortable only with women visiting the more private rooms on the upper level.

In Iran and India, some restaurants and parks are designated “men only” or “women only”. Many women view these “women only” areas as a safe place to gather and discuss issues, while others view them as discriminatory.

Cultural Regions

Cultural regions are usually determined based on characteristics such as religion, language, and ethnicity. Unless regions are defined by clear features, such as a mountain range, a transition zone often exists. In these zones, two cultures mix and people exhibit traits of both. Cultural regions do not always follow political borders. The border between the United States and Mexico clearly illustrates this pattern. People who live in border communities such as El Paso, Texas, are often fluent in both Spanish and English, and have cultural ties to both Mexico and the United States.

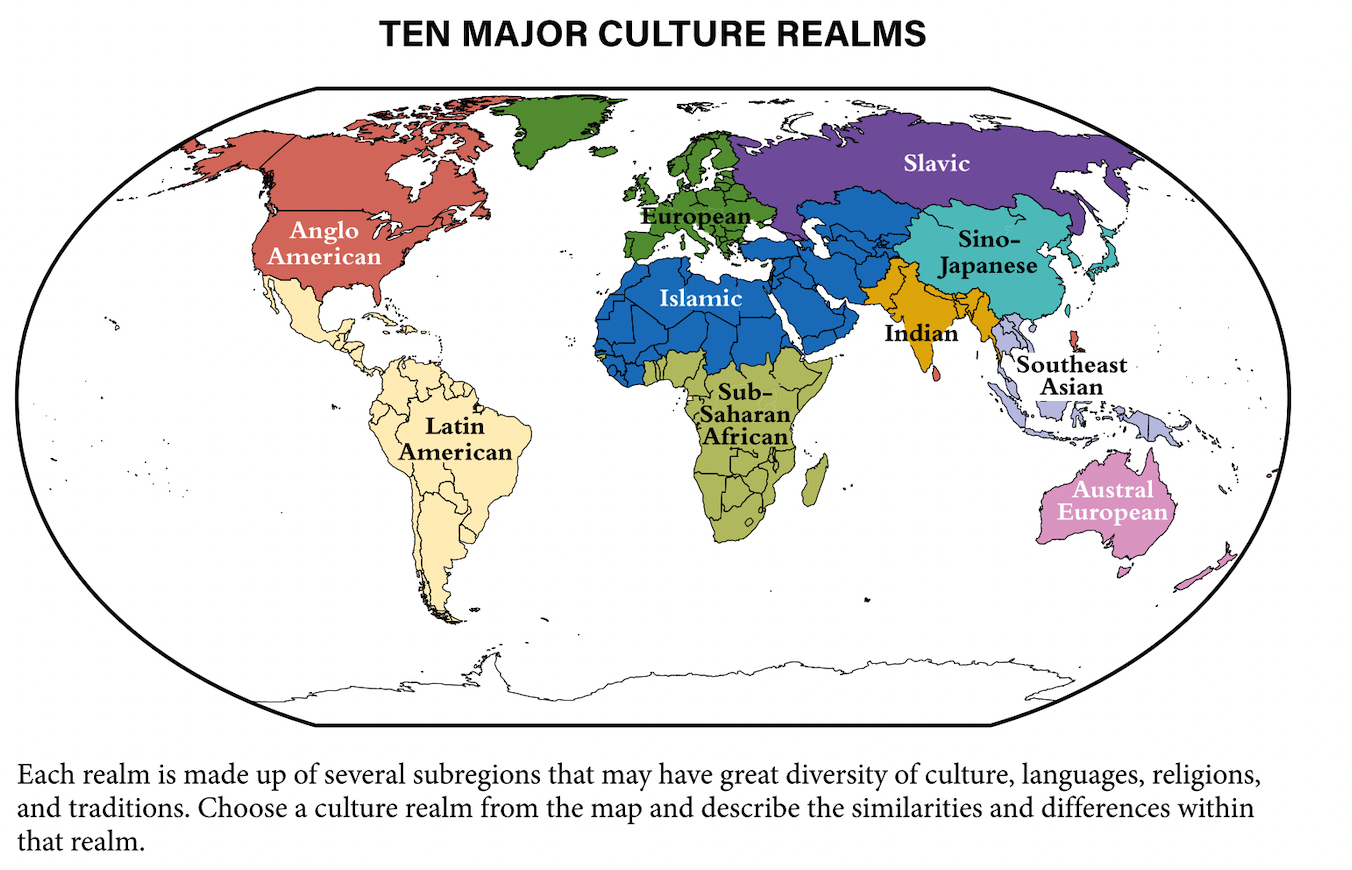

Realms

Geographers also identify larger areas, culture realms, that include several regions. Cultures within a cultural realm have a few traits that they all share, such as language families, religious traditions, food preferences, architecture, or a shared history. Some geographers view realms simply as very large regions.

Religion and the Landscape

Like all human activities, religion influences the organization and use of space. This appears in both how people think about natural features and what people build.

Sacred Space

Many specific places and natural features have religious significance and are known as sacred places or sites. Some sites are sacred spaces where deities dwell. For example, followers of Shinto view certain mountains and rocks as the homes of spirits. Other sacred sites are important for what occurred there.

Mt. Sinai is honored by Jews, Christians, and Muslims because they believe it is where God handed the Ten Commandments to Moses. Some entire cities have special religious meanings, such as Jerusalem (Israel), Mecca (Saudi Arabia), and Lhasa (Tibet).

Religious Cultural Landscapes

Sacred physical features are important, but rare. More commonly, people express their beliefs through the cultural landscapes they create:

- Memorial spaces to the dead, such as cemeteries, are traditionally located

close to worship spaces. - Restaurants and food markets often cater to particular religious groups

by offering religiously approved food. - Signs often are written in the language and sometimes the alphabet that

reflects the ethnic heritage of the group.

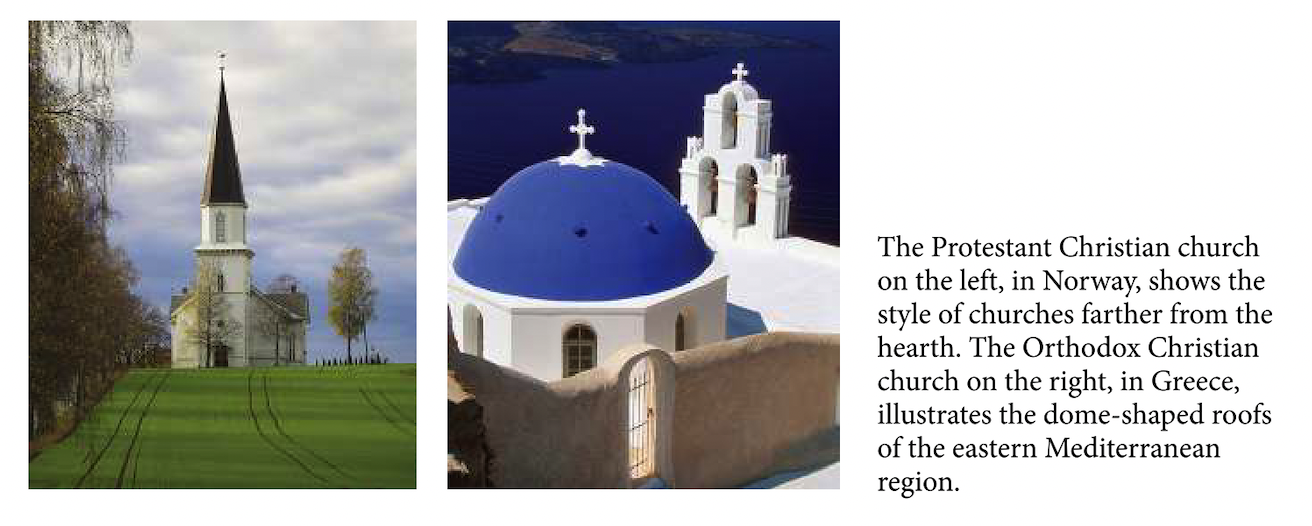

The most obvious example of the cultural landscape shaped by religion is in architecture. Each major faith provides examples of this.

Christianity

Christian churches often feature a tall steeple topped with a cross, as Christians believe Jesus was resurrected after dying on a cross. Churches also demonstrate how the origin of the architectural style was often influenced by the environment. The hearths of that faith are more likely to resemble the original architecture. Christian churches closer to the eastern Mediterranean tend to have dome-shaped roofs that reflect the traditional style of architecture popular with the Romans, while churches in northern Europe have steep-pitched roofs designed for snow to slide off in the winter. This was an environmental adaptation, as the build-up of snow on a flat roof can cause it to cave in. Cultural influences similarly shape the preferred and available materials to build such structures.

One similarity among Christians is in treatment of the deceased. In most parts of the world, Christians bury the dead in cemeteries, although types of cemeteries may vary greatly. Most burials are underground, but in New Orleans, where the water table is high, cemeteries are above ground.

Hinduism

Hindu temples often have elaborately carved exteriors with multiple manifestations of deities or significant characters. Thousands of shrines and temples dot the landscape in India since devout Hindus believe the

construction of these religious structures will reflect well on them. Sacred sites, such as the Ganges River, provide pilgrims a place to bathe for the purpose of purification. Many Hindu shrines and temples are located near rivers and streams for this very purpose.

Hindus practice cremation, the ritual burning of a dead body, as an act of purification as well. However, in some regions, a shortage of wood has made cremation very expensive. The ashes of the deceased are often spread in the Ganges River.

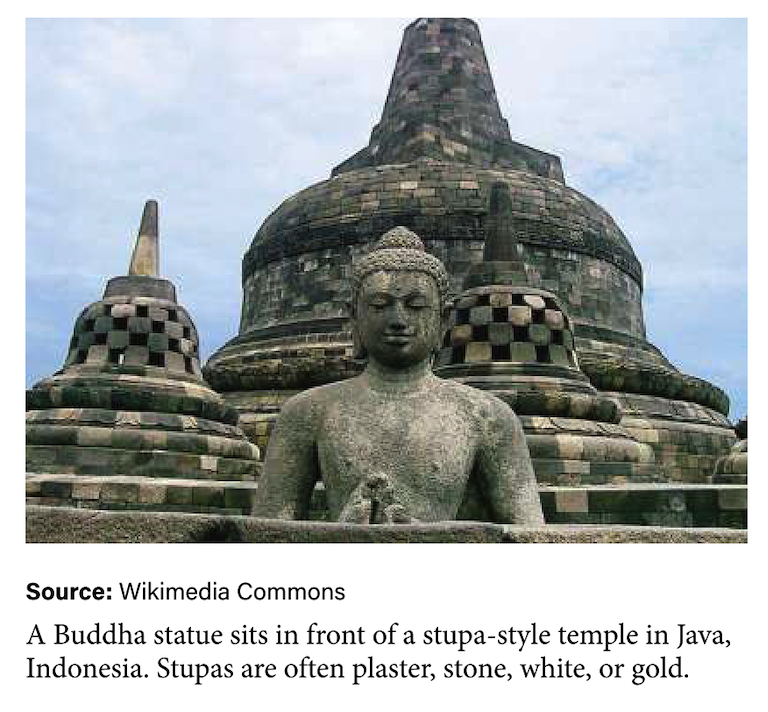

Buddhism

The practice of Buddhism differs widely from place to place and from ethnic group to ethnic group. However, most Buddhists emphasize meditating and living in harmony with nature. These features of

Buddhism are represented in stupas, structures to store important relics and memorialize important events and beliefs. Stupas were often built to symbolize the five aspects of nature-earth, water, fire, air, and space. Pagodas are also a common architectural style that developed from stupas, but unlike stupas, they are used as temples and people can enter into larger pagodas. Believers often meditate near both sacred spaces. Among Buddhists, the decision to cremate or to bury the dead is a personal choice and consequently the imprint on the cultural landscape differs. Burial sites for Buddhists are often marked with memorials of individuals or families and often serve as a sacred quiet space to meditate.

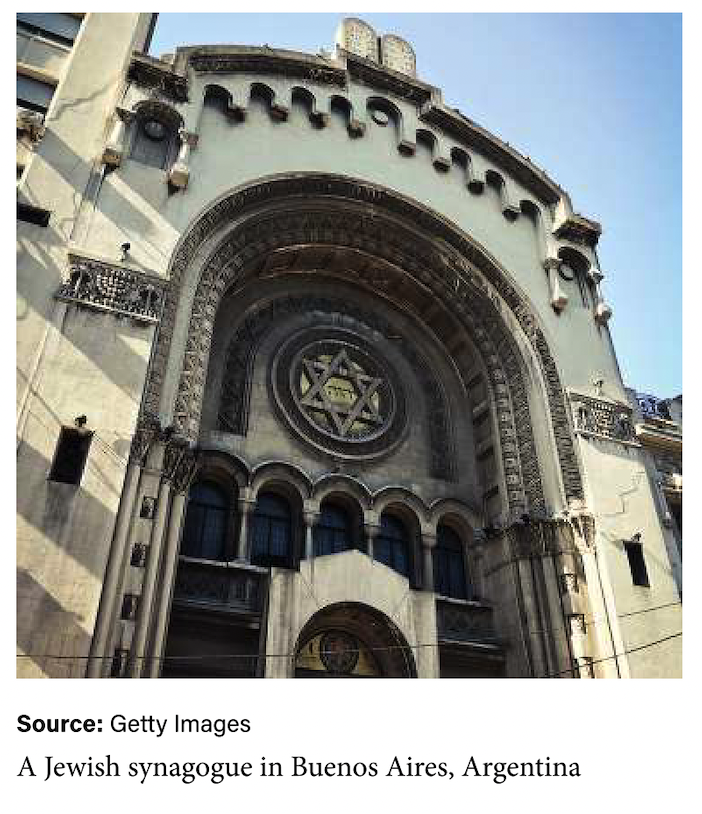

Judaism

Jews worship in synagogues or temples. Once concentrated in the Middle East Jews spread throughout the world because of exile or persecution, or through voluntary migration. This scattering is known as the

Diaspora. A diaspora occurs when one group of people is dispersed to various locations. Synagogues vary in size based on the number of lews in an area. Burial of the dead customarily occurs before sundown on the day following the death.

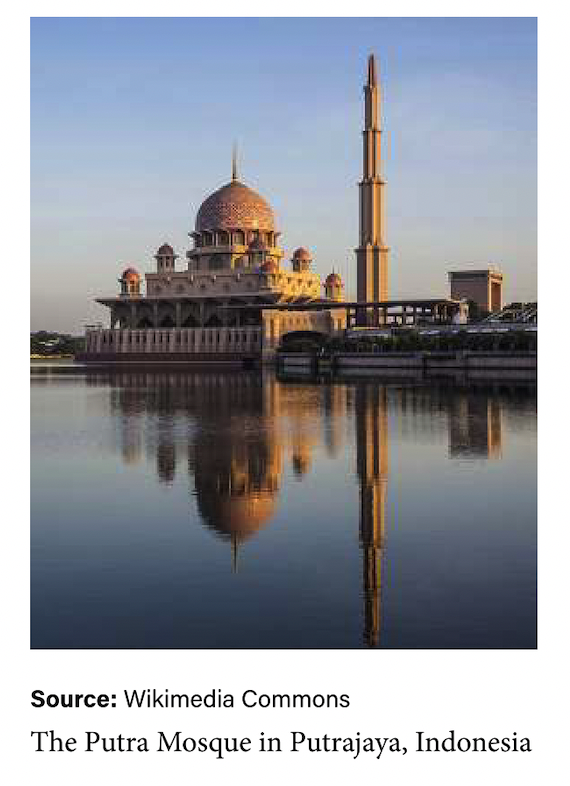

Islam

In places where Islam is widely practiced, the mosque is the most prominent structure on the landscape and is usually located in the center of town. Mosques have domes surrounded by a few minarets (Arabic for beacon) from which daily prayer is called. Burial of the dead is to be done as soon as possible, and burials are in cemeteries.

Shinto

Shinto, whose cultural hearth is Japan, emphasizes honoring one’s ancestors and the relationship between

people and nature. One common landscape feature of Shinto shrines is an impressive gateway, or tori, to mark the transition from the outside world to a sacred space.

How Religion and Ethnicity Shape Space

The first group to establish cultural and religious customs in a space is known as the charter group. Native Americans were the charter group in the Americas Their influence appears in many places, such as in place names from Mt. Denali in Alaska to Miami, Florida. Often, the cultural landscape of charter groups

shows their heritage. For example, English settlements in colonial America resembled the settlements they migrated away from in England, and names such as Plymouth and Jamestown reflect this heritage. The layout of these towns would often have a centrally located church, which also served as a meeting

hall for the community.

Ethnic Landscape

Ethnic groups that arrive after the charter group may choose to bypass the already established cultural location and create a distinctive space with their own customs. In urban areas, these enclaves become ethnic neighborhoods.

Rural Areas

In rural areas, ethnic concentrations form ethnic islands Their cultural imprints revolve around housing types and agricultural dwellings that reflect their heritage. Because ethnic islands are in rural areas and have less interaction with other groups than groups in cities, they maintain a strong and long-lasting sense of cohesion. Today, Germanic ethnic islands of people who fled religious persecution in the past continue to exist in the United States (the Pennsylvania Dutch and the Amish), Canada (Mennonites in Alberta), and in scattered locations in the Balkan region of southeastern Europe.

Urban Ethnic Neighborhoods

Ethnic neighborhoods in urban settings are often occupied by migrants who settle in a charter group’s former space. The charter group has already shaped much of the landscape, but new arrivals create their own influence as well. Dozens of cities around the world-Melbourne, Australia; Gachsaren, Iran; Liverpool, England; San Francisco–have neighborhoods known as “Chinatown. The name tends to live on even if the original occupants have moved out or assimilated, and the neighborhood primarily caters to tourists.

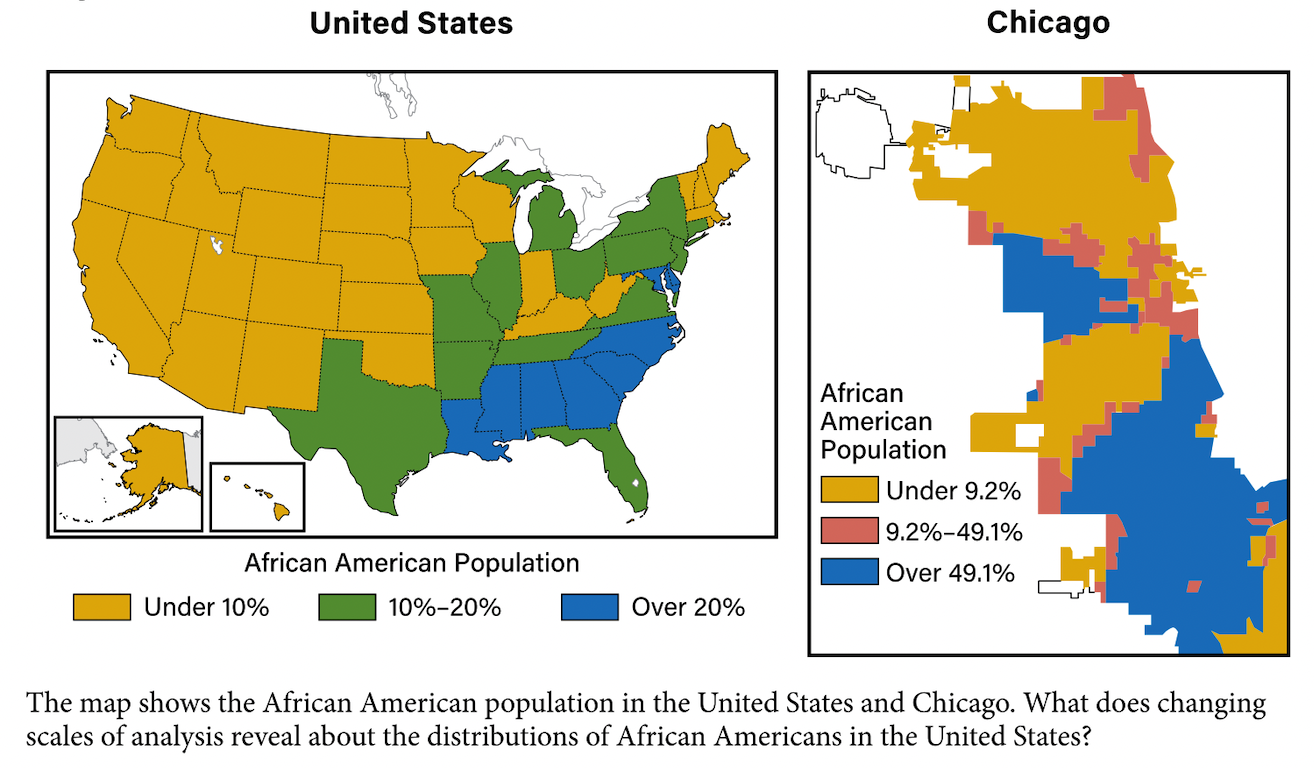

Frequently, members of a particular ethnic group cluster in particular regions. Group members might choose to live close together for cultural reasons. This is often true of immigrants or some religious groups. Some ethnic clusters have specific needs requiring special funding, such as funds to help preserve distinctive architecture or to provide English language training. Discrimination may limit the housing choices for members of a particular group. The most notable example of this were the practices in many cities that limited the neighborhoods where African Americans could live in the United States. As the maps below show, the distribution of African Americans varies based on scale. At the national scale, African Americans are concentrated in the southeast United States. At the state scale, they are often clustered in large cities. And at the city scale, African Americans are often clustered in particular neighborhoods.

New Cultural Influences

Ethnic groups move in and out of neighborhoods and create new cultural imprints on the landscape in a process geographers call sequent occupancy. In Chicago, the Pilsen neighborhood is heavily populated by Hispanics today, but its name recalls a history as a home for German and Czech immigrants. In New

York City, the neighborhood of Harlem has been home to many ethnic groups: Jews from Eastern Europe starting in the late 1800s, African Americans from the southern United States starting in the 1910s, and Puerto Ricans starting in the late 1900s. As a result of sequent occupancy, Harlem’s cultural landscape

includes former Jewish synagogues, public spaces named for African American leaders such as Marcus Garvey Park, and street names honoring Puerto Rican leaders such as Luis Muñoz Marin Boulevard.

Reactions to New Residents When new groups move into a neighborhood the process of change can be well received and result in positive changes.

However, the evolution and changing occupancy of neighborhoods can create cultural, economic and political tension. Tension often increases when the incoming group changes or destroys the cultural landscape without considering the people already living in the space. Conversely, existing residents can exhibit prejudices or resentment toward the group moving in. Assertions of Identity Asa result of global culture and changing occupancy patterns, the ideas, traditions, and history of communities can erode. Sometimes people respond with neolocalism, the process of re-embracing the uniqueness and authenticity of a place. For example, a neighborhood in a large city might hold a festival to honor the cuisine, religion, and history of the migrants who settled the community.

Cultural Patterns

Cultural patterns consist of related sets of cultural traits and complexes that create similar behaviors across space. Geographers are particularly interested in understanding cultural patterns across time and space, specifically, patterns of cultural components such as religions, ethnicities, and nationalities. The

diverse tapestry of cultures creates a rich local and global cultural landscape that enhances placemaking. The effects of these patterns have the power to bring people together or tear them apart. Patterns are powerful.

Religious Patterns and Distributions

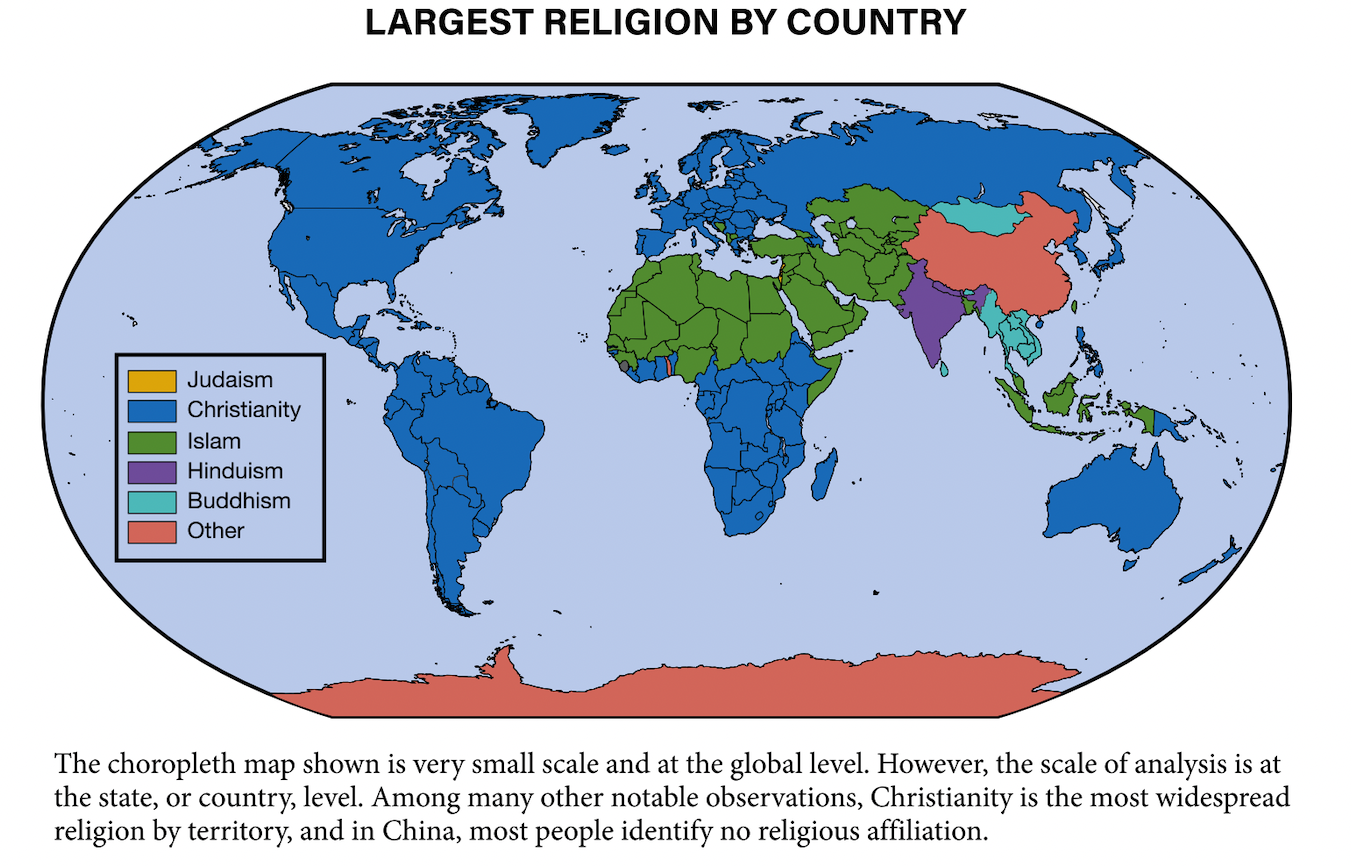

Developing strong mental maps of the origins, diffusion, and distribution of major religions and their divisions is one of the most valuable ways to understand culture. Geographers start by mapping a culture hearth, where a religion or ethnicity began, and then track its movement and predict its future direction. Religions, like other elements of culture, often diffuse outward from their hearths in various ways. The spread of religious settlements, both locally and globally, contributes to the sense of place and of belonging for each religious group and greatly shapes the cultural landscape.

Geographers analyze maps, charts, and other data to understand the growth, decline, movement, and cultural landscapes of the world’s religions. They have traced the geographic patterns of each major world religion, including the religion’s hearth, the geographic spread of the religion, and practices that can

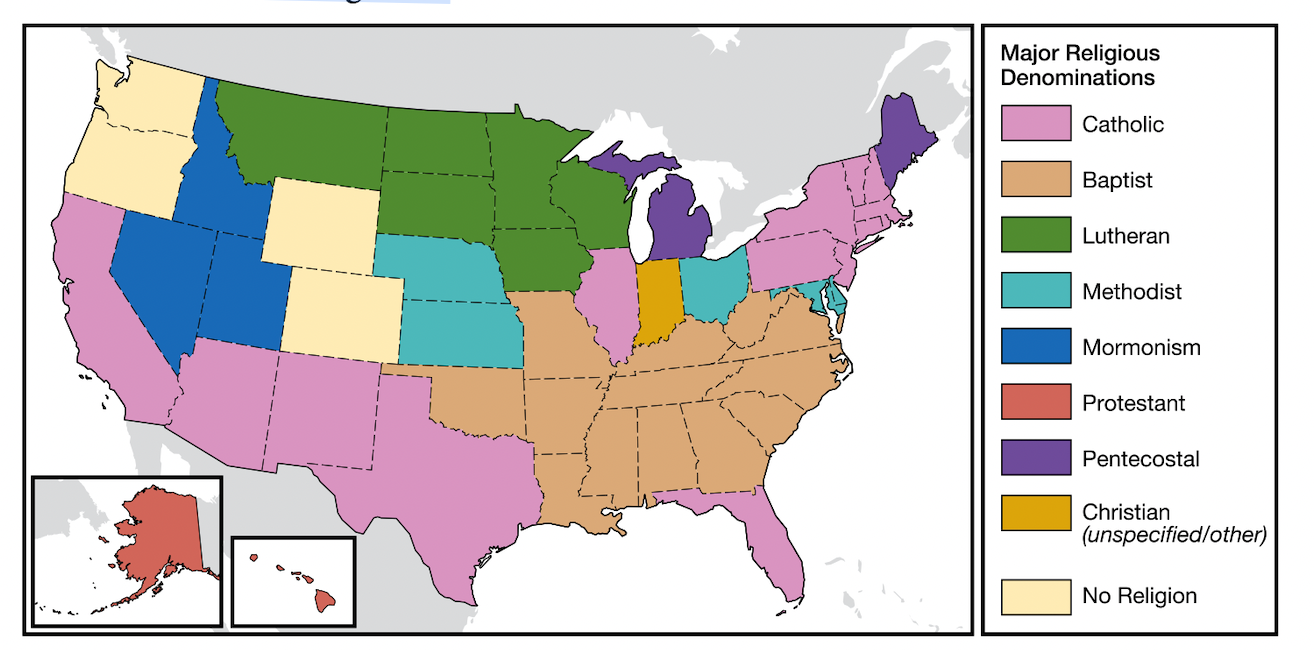

influence both the culture and the cultural landscape. Regional Patterns in U.S. Religion

The distribution of ethnic and religious groups in the United States reflects historical patterns:

- Congregationalists are still strong in New England, where their English

ancestors settled in the 1600s.

Baptists and Methodists are most common in the Southeast, where these

denominations were spread by traveling preachers in the 1800s.

Lutherans live mostly in the Midwest, where their German or

Scandinavian ancestors, who immigrated in the late 1800s, could find

good farmland. - Many Mormons live in or near Utah, where their founders settled in the

mid-1800s after religious persecution drove them out of Missouri and

Illinois.

Roman Catholics are most common in urban areas in the Northeast and

throughout the Southwest. - Jews, Muslims, and Hindus live most often in urban areas, the traditional

home to immigrants.

Cultural Variation by Place and Region

Patterns and landscapes of religious and ethnic groups vary by place and region at different scales. The world map above shows that the United States is mostly Christian; however, the scale of the data hides the fact that the United States has great religious diversity. The map above does show data aggregated by state and can show the breakdown and spatial patterns of other religions. For example, the world map doesn’t show the breakdown of Roman Catholics and Protestant Christians. Additionally, at the regional level within the United States, Baptists are the most common religious group in the Southeast, but this cannot be seen on the world map.

Religion, Ethnicity, and Nationality

Religion is often closely linked to ethnicity, or membership in a group of people who share characteristics such as ancestry, language, customs, history, and common experiences. Most geographers distinguish between nationality based on people’s connection to a particular country-and ethnicity-based upon group cultural traits. For example, Russian Jews make up a different ethnicity than Russians in general Geographers often study ethnic groups as minorities within a greater population. To do so, they focus on mapping and analysis to trace the movement of ethnic groups and investigate their spatial dimensions and cultural landscapes. People often identify with both their ethnicity and nationality but the order of identification is a very personal process. In the United States, many Hispanics identify their nationality as American first, and then ethnically as Hispanic; others reverse the order.

Centripetal and Centrifugal Forces

Understanding cultural patterns requires consideration of centripetal and centrifugal forces. Centripetal forces are those that unify a group of people or a region. These forces may include a common language and religion, a shared heritage and history, ethnic unity and tolerance, a just and fair legal system a charismatic leader, or any other unifying aspect of culture. People tend to gravitate toward other people who share their beliefs, customs, interests, and background.

The United States has great religious and ethnic diversity, but the holiday season from November through December has unified many Americans German and Scandinavian immigrants, among others, enjoyed the camaraderie of shared values and experiences, of holidays like Christmas. The German cultural trait of adorning Christmas trees diffused throughout the United States and has established itself as a part of American culture Today, many people who do not celebrate Christmas as a holy day still consider the Christmas tree as a part of their culture.

Centrifugal forces are those that divide a group of people or a region. These forces can pull apart societies, nations, and states, and are essentially centripetal forces in reverse. Different languages and religions, a separate past, ethnic conflict, racism, unequal application of laws, or dictatorial leadership

are just a few of the many cultural attributes that can sow division within a society.

Centrifugal forces can be especially harmful toward national cohesion in multicultural states, those which possess more than one distinct cultural identity or ethnic group within its borders. Ireland was historically Catholic since the 5th century. However, as England became Anglican-a Protestant denomination- this cultural influence extended into Northern Ireland through invasion and migration. While Catholics and Anglicans are both Christians, the competition over territory, political power, and cultural influence drove the region into repeated violence over centuries.

In Iraq, Islam is dominant. However, there are regional divisions between the Shite majority in the east and the Sunnis in the west. Ethnically, the majority of Iraqis are of Arabic heritage, yet there is a significant concentration of Kurds throughout northern regions of Iraq. (See Topic 4.3.) While cultural differences

may lead to friction between groups, the competition for land, resources, and the desire for greater autonomy has also occasionally erupted into violence.

Religion’s Impact on Laws and Customs

Since religious traditions predate current governments, they are often the source for many present-day laws and punishments by the government. Some religions have strict systems of laws that have been adopted fully by governments. An example of this is Sharia, or the legal framework of a country derived from Islamic edicts taken from their holy book, the Quran. Sharia has been adopted by some fundamentalist religious groups, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan, as the law of the land.

While no highly industrialized countries have fully adopted religious laws, their legal codes often show clear influence of religion. In the United States, many communities have blue laws, laws that restrict certain activities, such as the sale of alcohol, on Sunday. In Colorado and some other states, car dealerships must be closed on Sunday as well.

In most countries, religious beliefs are more influential as guides to personal behavior than as state-sponsored laws. For example, many faiths include guidelines on the choices people make about what clothes they wear and how they cut their hair. Most faiths include some food taboos, prohibitions against eating and drinking certain items. For example, many Hindus do not eat beef, and many Jews and Muslims do not eat pork.

Religion is also the source of many daily, weekly, or annual practices for adherents: Many Muslims pray five times a day, and many Buddhists and Hindus engage in daily meditation. Most religions have weekly religious services for worship or instruction For example, Muslims usually gather on Friday, Jews on Friday evening or Saturday morning, and Christians on Sunday.

- Many people celebrate important religious holy days, such as Holi-

-a festival of light for Hindus–and Vesak- which commemorates the birth

of Buddha. - In addition, many days that people now commonly treat as secularized

holidays have their roots in religious practices. Valentine’s Day, St. Patricks

Day, and Mardi Gras all originated as Christian holy days.

Religious Fundamentalism

The degree of adherence to tradition varies within each religion. Every religion includes followers who practice fundamentalism, an attempt to follow a literal interpretation of a religious faith. Fundamentalists believe that people should live traditional lifestyles similar to those prescribed in the faith’s holy writings. In some traditions, this means that women are likely to leave school at a young age, to live in an arranged marriage, and to avoid working outside the home Fundamentalists are more likely than others in their faith to enforce strict standards of dress and personal behavior, often through laws.

The strength of fundamentalism often diminishes with greater distance from the religious hearth, which is known as distance decay. (See Topic 1.4.) For example, the hearth of Islam is the Arabian Peninsula, and where Islamic fundamentalism has long been strongest. Fundamentalism is less prevalent in Muslim-majority countries farther from the hearth, such as Malaysia and Indonesia. One way to measure fundamentalism in Islam is by the role of Sharia.

In countries where Sharia dominates, there is no separation between religious law and civil law. Sharia is strongest in countries of the Arabian Peninsula such as Saudi Arabia and Yemen. Some fundamentalist countries, such as Iran, are theocracies, countries whose governments are run by religious leaders through the use of religious laws. Iran follows Sharia and the nation’s leader, the Supreme Leadership Authority, is not only the political head of the state, but concurrently its highest religious authority. Fundamentalists often clash, sometimes violently, with those who wish to follow religious traditions more loosely or to live a

more secular lifestyle. All major religions of the world–including Christianity Buddhism, Hinduism, and Judaism- have a history of theocracy and each have some adherents who are fundamentalists.

Cultural Ethnocentrism and Relativism

Most states are multiethnic in that they possess a significant number of people who do not identify with the national majority as their own ethnic group. If people are more ethnocentric, they believe their own cultural group is more important and superior to other cultures. In many cases, they see others by means of generalizations and stereotypes, and often do not seek to understand different customs or cultural norms. While loyalty and pride in one’s own culture is common and understandable, ethnocentric views typically lead to misinterpretations of others and the value they give certain artifacts and mentifacts.

Without consciously pursuing an understanding of other cultures, a “we” versus “them’ mentality can grow. Ethnocentrism may lead to centrifugal forces within a state, such as discrimination, intolerance, violence, and mass killings. The same attitude may lead to issues with other states, including misunderstandings, increased tension, or even war.

A counter to ethnocentric views has been cultural relativism, which is the concept that a person’s or group’s beliefs, values, norms, and practices should be understood from the perspective of the other group’s culture. Groups have developed their identities often through years–if not centuries-of environmental adaptation, interaction with other cultures, changing internal attitudes, and technological innovation. For example, many Americans are disgusted when some cultures eat fried insects. Applying cultural relativism, a geographer would attempt to understand why some communities may eat bugs. They would learn that other sources of protein were not available. This available food source was essential to survival and became ingrained in the community’s culture over time.

Cultural appropriation is the action of adopting traits, icons, or other elements of another culture. The greatest concern is when the trait is adopted by the majority culture from a minority, or oppressed, cultural group. Concern increases if the trait is used out of context (not understanding the meaning of trait) or in an inappropriate or disrespectful way. An example would be naming sports teams after indigenous people or dressing up in costumes that propagate racial or cultural stereotypes.

Understanding other cultures from the inside affords everyone the opportunity to foster communication that leads to empathy and mutual respect. The culture-relativist perspective generally leads to centripetal forces within multiethnic societies and to vastly improved relations between states.