The costs and rising expectations of parenthood are making young people think hard about having any children at all

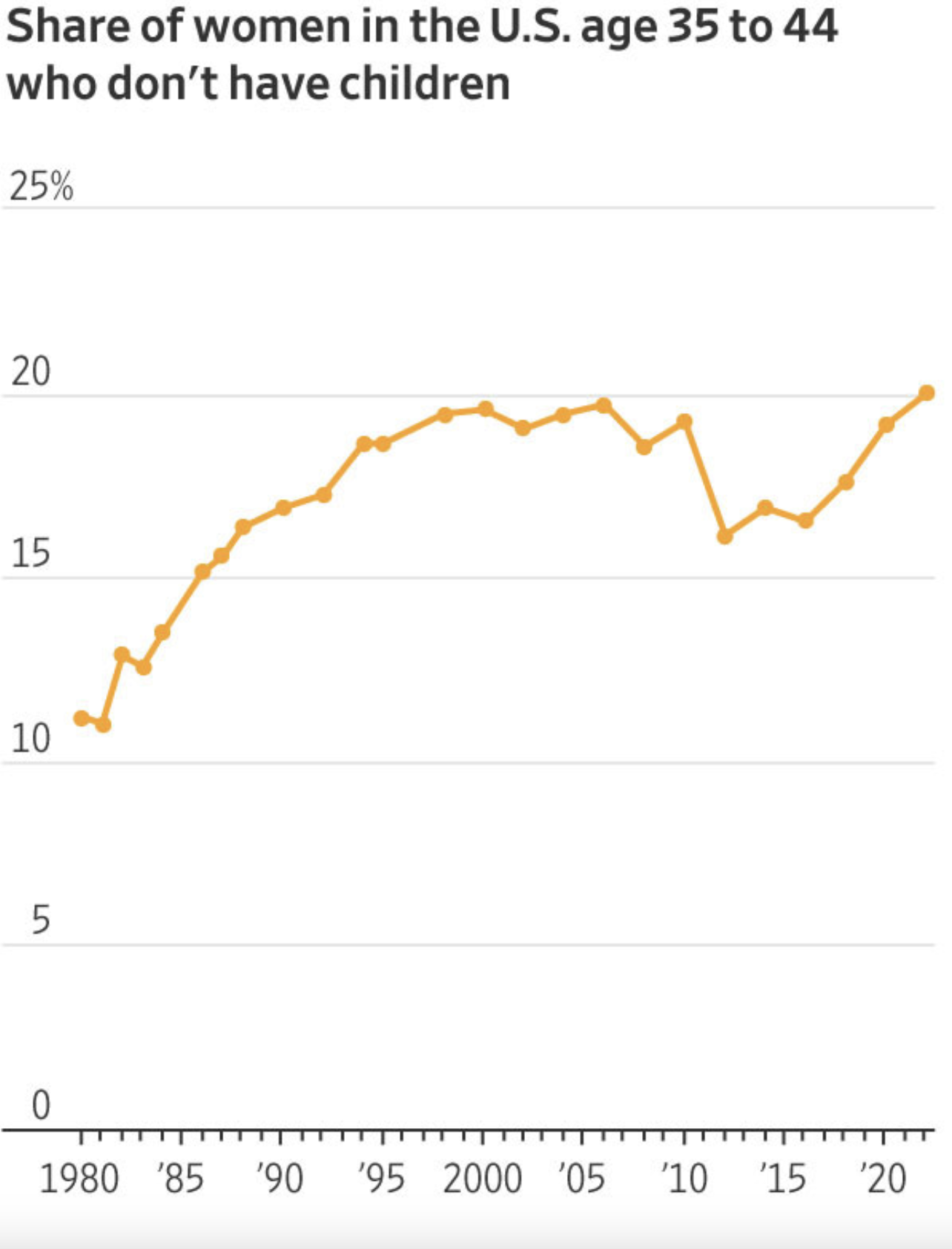

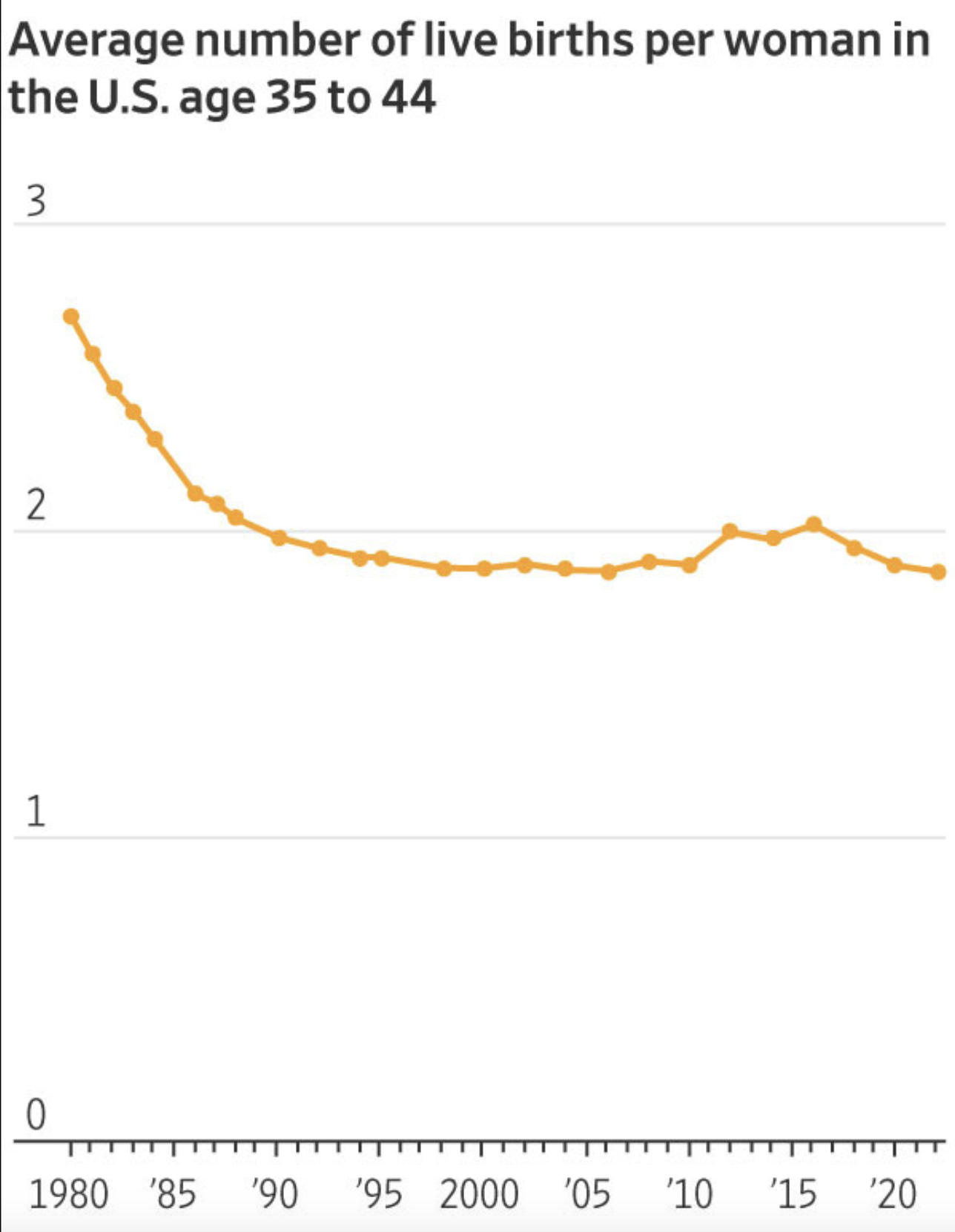

Americans aren’t just waiting longer to have kids and having fewer once they start—they’re less likely to have any at all.

The shift means that childlessness may be emerging as the main driver of the country’s record-low birthrate.

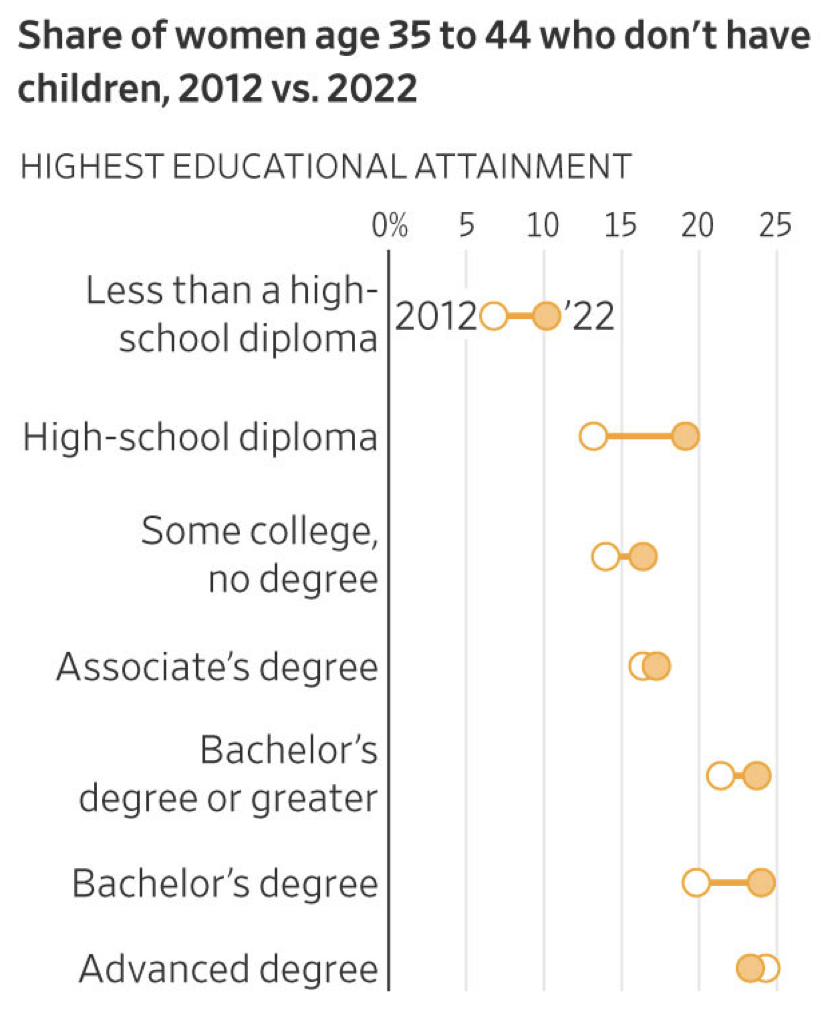

Women without children, rather than those having fewer, are responsible for most of the decline in average births among 35- to 44-year-olds during their lifetimes so far, according to an analysis of the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey data by University of Texas demographer Dean Spears for The Wall Street Journal. Childlessness accounted for over two-thirds of the 6.5% drop in average births between 2012 to 2022.

While more people are becoming parents later in life, 80% of the babies born in 2022 were to women under 35, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Vital Statistics data.

“Some may still have children, but whether it’ll be enough to compensate for the delays that are driving down fertility overall seems unlikely,” says Karen Benjamin Guzzo, director of the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

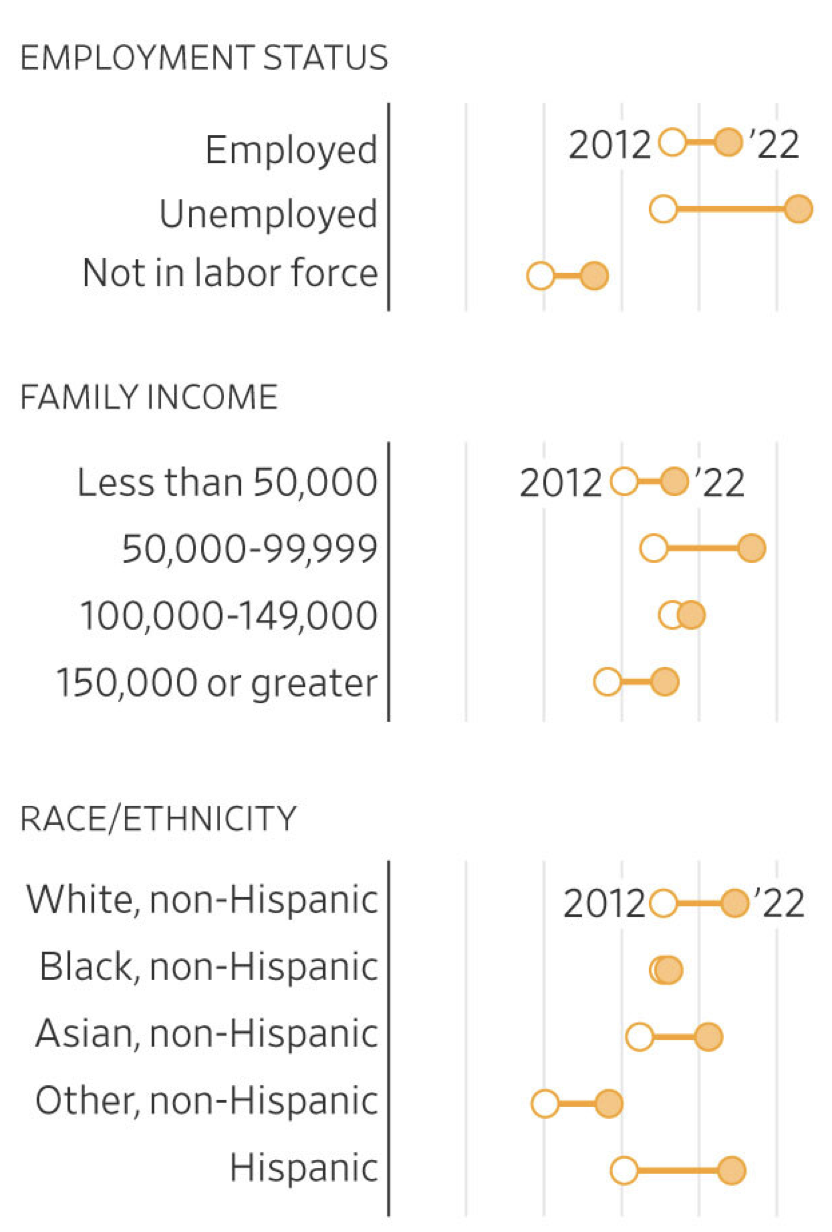

The change is far-reaching. More women in the 35-to-44 age range across all races, income levels, employment statuses, regions and broad education groups aren’t having children, according to research by Luke Pardue at nonprofit policy forum the Aspen Economic Strategy Group.

Birthrates among 35- to 44-year-olds give demographers who study fertility an early look into millennials’ changing approach to parenthood. But these researchers also look closely at women over 40, reasoning that if a woman doesn’t have a child by then, she is more likely to remain childless.

The number of American women over 40 who had no children was declining until 2018, according to Current Population Survey data, when it then began to rise again. Now, some demographers and economists expect the increase in childlessness will be sustained due to shifts in how people think about families.

In New Orleans, 42-year-old Beth Davis epitomizes some millennials’ new views. “I wouldn’t mess up the dynamic in my life right now for anything, especially someone that is 100% dependent on me,” she says.

‘What Are Children For?’

Throughout history, having children was widely accepted as a central goal of adulthood.

Yet when Pew Research Center surveyed 18- to 34-year-olds last year, a little over half said they would like to become parents one day. In a separate 2021 survey, Pew found 44% of childless adults ages 18 to 49 said they were not too likely, or not at all likely, to have children, up from 37% who said the same thing in 2018.

As more women gained access to birth control and entered the workforce in the 1970s, reshaping family life and expectations around gender, Americans began having fewer kids. By 1980, the average number of children per family was 1.8, down from a high of 3.6 during the post-Depression baby boom, according to Gallup.

Now, researchers say, having children at all has begun to feel optional.

“To be a human being, for most people, meant to have children,” says Anastasia Berg, co-author with Rachel Wiseman of the new book “What Are Children For?: On Ambivalence and Choice.”

“You didn’t think about how much it would cost, it was taken for granted,” she says.

But unlike their parents and grandparents, the authors say, younger Americans view kids as one of many elements that can create a meaningful life. Weighed against other personal and professional ambitions, the investments of child-rearing don’t always land in children’s favor.

With less pressure to have kids, economists say, more people feel they need to be in the ideal financial, emotional and social position to begin a family.

Giovanni Perez, 38, has been trying to convince his wife, Mariah Sanchez, 32, that they’re ready to become parents.

“People less well-off than us are having kids and I see it every day, and I’m pretty sure we could do better than most of them,” says Perez, an after-school art teacher in the Bronx, N.Y.

Sanchez isn’t sold.

With a single mom during her early childhood and a brother 15 years her junior, Sanchez grew up helping with diaper changes and bottle feedings. Before she has kids of her own, she wants to move from the couple’s one-bedroom apartment into a bigger place. She also hopes to climb the ranks at the advertising agency where she works, ideally doubling their combined income of $100,000.

“I know what it’s like for a child whose parent wasn’t prepared for them,” says Sanchez. Still, she admits, the amount she thought she needed to earn before having children was far lower a few years ago. “It feels like a moving target,” she says.

Her mom, Michelle Morales, had Sanchez when she was 21. That was late by her Brooklyn community’s standards, she says. (A dramatic drop in teenage births is another factor driving the fertility rate down.)

“There was no planning for kids, you just had them,” says Morales, a 53-year-old college adviser in Naples, Fla.

While she worries she may never be a grandparent—“which I’d like to experience before I leave this Earth”—she respects the intention with which her children are approaching parenthood.

“These kids are a lot smarter in making decisions for themselves,” she says.

How much kids actually cost

Nobody will dispute that kids are expensive. Whether they have become more so in recent years—and the extent to which that is driving down birthrates—is more complicated.

Parents are spending more on their children for basics such as housing, food and education—much of that due to rising prices. Another factor, however, is the drive to provide children with more opportunities and experiences.

Middle-class households with a preschooler more than quadrupled spending on child care alone between 1995 and 2023, according to an analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics and Department of Agriculture data by Scott Winship at think tank the American Enterprise Institute.

Yet only about half of the increase is due to rising prices for the same quality and quantity of care. (Child care prices are up 180% overall since the mid-90s, according to BLS data.)

The remaining half is coming from parents choosing more personalized or accredited care for a given 3- to 5-year-old, or paying for more hours, Winship says.

“People say kids are more expensive, but a lot of this comes from parenting becoming more intensive so people are spending more on their kids,” says Melissa Kearney, an economist at the University of Maryland who researches children and families.

It has always been costly and time-consuming to raise kids, she says, and it has always come into conflict with other priorities. What’s changed is that more people are deciding not to have children at all.

“If it were socially acceptable for people in the past to remain childless, I wonder how many of them would have made the same decision,” Kearney says.

‘My autonomy’

Beth Davis loves her niece and nephew. But she isn’t envious of how much time and money her siblings spend bouncing between volleyball tournaments, baseball games and trips to the mall to replace outgrown clothes.

Davis, who works in marketing, and her husband, Jacob Edenfield, 41, both say they always expected to hit a moment when they, too, wanted to become parents. When that still hadn’t happened by the time they started dating in their mid-30s, they decided to start reorienting their lives.

“People told me when I was younger, ‘Oh, you’ll grow into it, you’ll develop those feelings, you’ll want to start a family,’ and that just did not happen,” says Edenfield, a creative director.

They moved to New Orleans a year ago in search of the city’s joie de vivre—and other childless millennials.

With a combined income of $280,000, the couple is able to put about $4,500 a month toward what they hope will be a mid-50s retirement. Another $2,600 pays rent on a sprawling Creole townhouse. The remaining $8,000 or so—much of which they assume would have been eaten up by child-rearing—goes primarily toward enjoying their lives.

Edenfield takes a class at a holistic wellness center. He is also working on a novel.

The couple often dines at the city’s upscale restaurants (including two recent $700+ dinners), regularly works out at a high-end wellness center and recently paid cash for a BMW. Edenfield meditates for an hour every morning and works on the novel he’s writing at the local corner bar many nights. For companionship, the couple fosters a rotating cast of Bengal cats.

Edenfield’s sibling, Caitlin Hopkins, was inspired in part by her brother and sister-in-law’s lifestyle to also remain childless. While she and her husband, Will, love kids, they say they would rather focus on being the best possible aunt and uncle. “And then I get to still have my autonomy and routine,” says Caitlin, a 35-year-old oyster farmer in Portland, Maine.

Changed expectations

The longer people wait to have kids, research shows, the less likely they are to have them.

O ne reason is biological: Women 35 and older are at increased risk of infertility and pregnancy complications. The other is social. People who already have fully formed adult lives are more reluctant to give up their freedom, says Brown University health economist Emily Oster. “All of a sudden you’ve chosen a different identity,” she says.

Trevor Galko and Keri Ann Meslar, 44 and 42, both grew up in the suburbs assuming kids were in their futures.

“I had never known someone that was 40 and married without kids, that would have been the weirdest thing I had ever heard,” says Galko, who works in software sales from Arlington, Va.

The couple, now engaged, dated for three years in their 20s before spending the next decade in other relationships, thinking kids would happen someday. But when they got back together in 2019, they decided they were too old and too set in their existing lives to start a family of their own.

While they both mourned that other possible path, they say they are content and have no regrets. Much of their disposable income now goes to travel, including recent trips to Greece, Spain and Guatemala in the span of three months.

For Meslar, who works in growth strategy for a CBD company, part of the justification for leaning into her kid-free reality was wanting to avoid making the same sacrifices she saw her parents make.

She says she can’t remember her mom or dad buying anything new for themselves while she was growing up so they could afford for her and her three siblings to join sports leagues and attend out-of-state colleges.

“I don’t think I could really live up to the example they set. Or I think I could, but I don’t think it would bring me the same joy,” she says.

MJ Petroni and Oleg Karpynets both went into their 20s wanting to be dads. Now in their late 30s, the couple no longer sees children in their future.

“ It was almost shocking to me when I realized having a fulfilling life didn’t necessarily include my own kids,” says Petroni, 39, who runs an artificial-intelligence strategy firm from home in Portland, Ore. For 38-year-old Karpynets, who runs a neighborhood library, that has meant going back to school to get his business administration degree, hosting monthly parties sometimes with over 100 people and going out with friends whenever he wants.

An only child, Petroni says continuing the family name and giving his parents grandchildren was “always just kind of a given” during his suburban upbringing on the central coast of California. More recently, however, it’s his parents who have required care. He says he’s spent over $100,000 on their medical and living expenses, as well as travel to visit them, over the past three years.

MJ Petroni and his husband, Oleg Karpynets, in Portland, Ore

“I would like to be able to put more toward that than I’m currently able to,” he says, adding it would be more difficult to do so if the couple decided to have kids.

The other side of that coin, points out Oster, the Brown University researcher, is how an increase in childlessness will play out as millennials age.

“A lot of our social structures kind of assume when people get old the person who is responsible for them is their children,” Oster says.

Climate concerns

When Allie Mills and Connor Laubenthal get married next year, they’ll be flanked on both sides of the altar by friends and family members who they say mostly intend to remain childless.

“With geopolitical issues, climate change, it’s like what are you bringing them into and then dropping them off and saying, ‘good luck!’” says Mills, who is 27 and works for a tech company. “There’s no real confidence that things are going to get better.”

Mills, who was raised in an evangelical Christian household, says her mindset is a radical departure from growing up wanting to be a mother and a homemaker. She struggles with anxiety, and worries how her own mental health would affect a child. And though her email signature proudly displays her status as “dog mom of two,” she says the only form of human parenthood she could picture at this point is fostering.

The couple’s other consideration is financial. Despite both having well-paying jobs, they say they haven’t been able to afford a house in Boston, where they live, amid low supply and high interest rates.

Laubenthal, a 27-year-old asset manager, calculated that they could retire at 55 with the same spending power if they don’t have kids. He then did the math to account for two children, factoring in costs of daycare, college, clothing and other essentials. That pushed their retirement back by 13 years, to age 68.

“That’s a big gap,” he says. His conclusion: Retire early, and skip kids.

Davis and Edenfield foster cats in their spare time, which Davis says would be more difficult if they had kids.