Concepts to Understand

benefits of a global food production system

effects of global production system in less developed countries

advantages of wealthy countries in global food production

Example of Interdependence

Ukraine

grain farming & exports

war with Russia

Globalization has become a firmly entrenched aspect of the economy of most countries, particularly in food production. Part of this has been the spatial expansion of the supply chains, all the steps required to get a product or service to customers. The physical distance from producers to consumers can cover thousands of miles. For example, research and development of new seeds might take place in a laboratory in the United Kingdom. The new seeds could then be sent to Ghana where the crop is grown and harvested. After some minor processing or refining in Ghana the product could be frozen and transported to China where it is manufactured into a finished product. Once packaged, it could be sent to the United States where it is sold to consumers. The level of interdependence, or connections among regions of the world has increased greatly. If one country experiences a problem such as crop failure, damaged infrastructure, or disruptions in trade due to political decisions, the repercussions could be significant for many countries.

Regional Interdependence

The globalization of agriculture has increased interdependence among countries of differing levels of development. Developed countries such as the United States rely on producers in Mexico, other countries with warm climates, and ones in the Southern Hemisphere, for fresh fruits and vegetables year-round.

Food on a Global Scale

Developed countries also sell food to around the world. For example, nearly half of U.S.-grown soybeans are exported. Purchasers of significant amounts of U.S. agricultural products include China, Mexico, and countries in Europe.

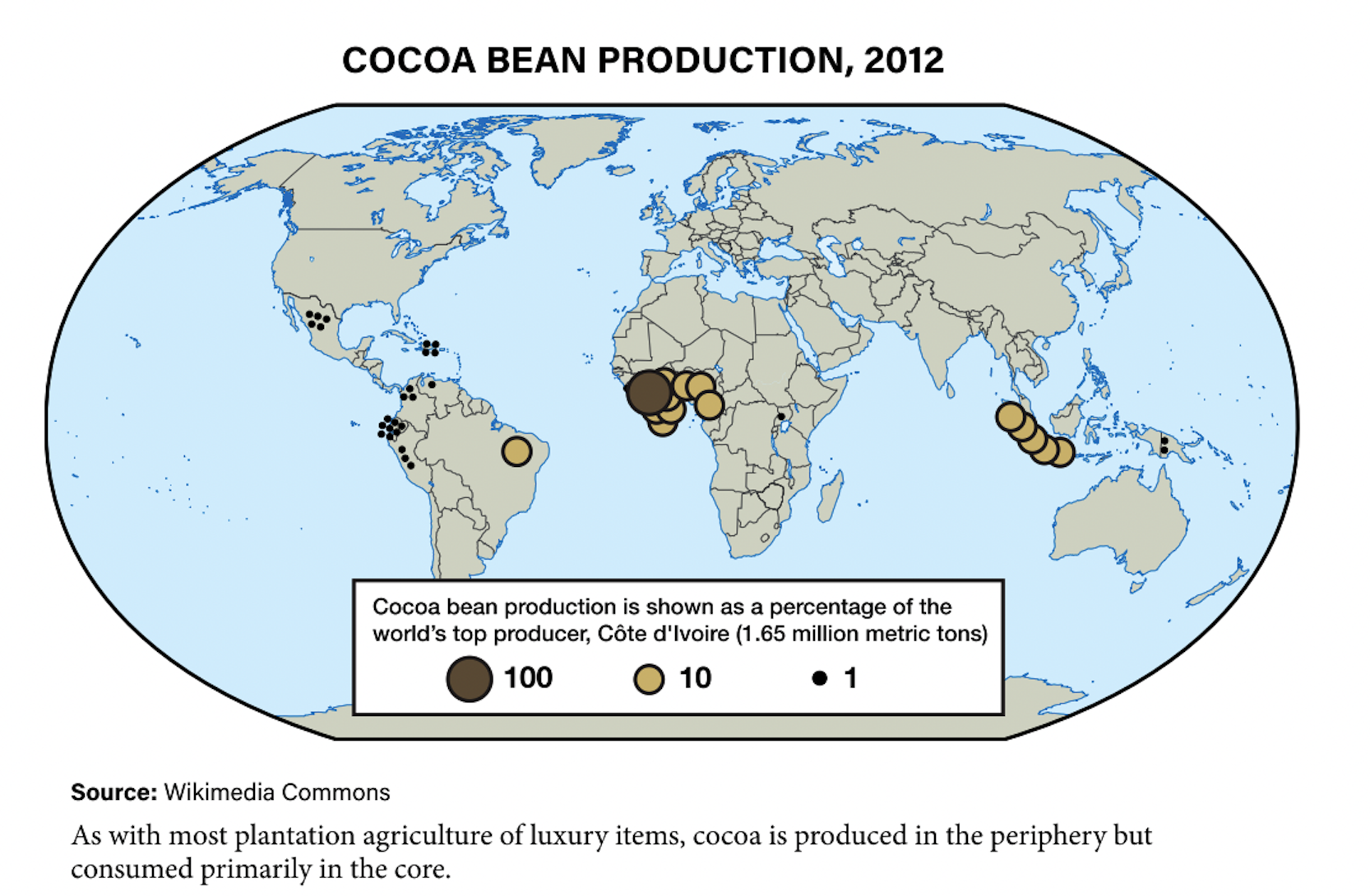

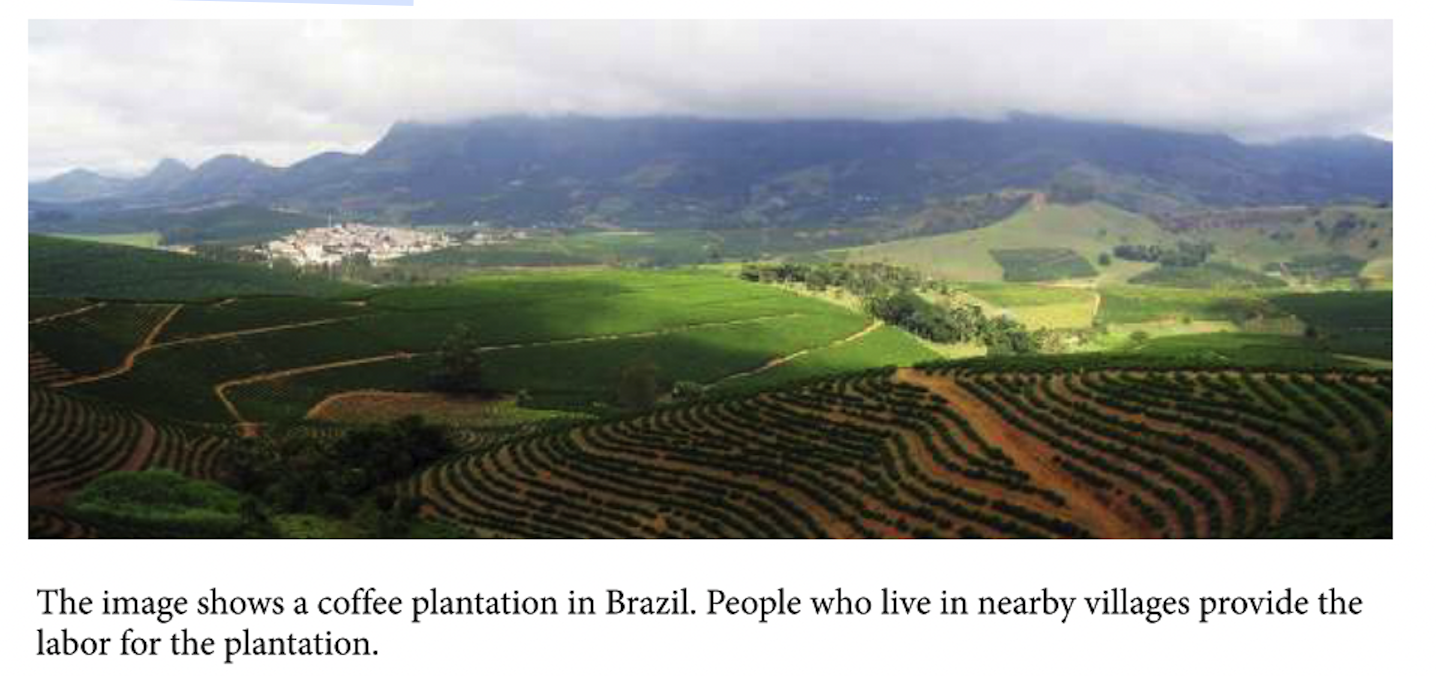

Low-latitude countries with tropical climates produce crops such as coffee, tea, bananas, and pineapples that are desired in core countries. Luxury crops are not essential to human survival but have a high profit margin. These crops including cocoa beans, which are eventually processed into chocolate, are often grown on large plantations commonly controlled by transnational companies. Plantations usually practice monoculture, specializing in only one crop. The transnational companies, which are usually controlled by shareholders in core countries, provide the capital necessary to develop and run the plantations. They take advantage of the opportunity for inexpensive land and labor, and a favorable climate. In some situations, they also take advantage of weak labor and environmental laws, which allow them to reduce costs and increase profits.

For periphery and semiperiphery countries, the globalized commodity chain provides both markets for products and problems:

Farmers who produce luxury crops might not be able to afford to purchase what they produce.

As the supply of locally grown food decreases, prices for local consumers can increase. A farmer in Honduras who grows chili peppers for the global market is not growing corn, beans, or other foods for local consumers.

Countries may become very dependent on one or two export commodities. When global markets shift these countries’ economies become vulnerable and unstable.

Competition to sell products might cause farmers to follow practices that cause soil erosion or chemical pollution, which endanger the long-term use of the land.

Political Systems, Infrastructure, and Trade

The efficient exchange of food around the world depends on effective political systems, strong infrastructure, and supportive trade policies. These conditions have evolved over time to make agricultural trade vital in most countries.

Colonialism and Neocolonialism

Many connections that exist between Europe and the developing world were established through colonization. Although there are very few colonies in the world today, the economic relationship between core countries and periphery and semiperiphery countries resembles certain aspects of colonialism. Neocolonialism, the use of economic, political, and social pressures to control former colonies, can be one way to describe the current state of global food distribution.

For example, while growing and processing coffee beans is expensive, the profit margin in selling brewed coffee drinks is very high. Most of the revenue generated from coffee remains with the transnational corporation based in the wealthy country while very little revenue finds its way back to the coffee growers in developing countries.

Fair Trade

In recent years, many consumers have become more aware of the disparity between the high incomes of those in developed countries, who manage trade, and the low incomes of the producers in the developing world. One result of this awareness is the fair trade movement, which started with the Fair Trade certificates for coffee in 1988. It is an effort to promote higher incomes for producers and more sustainable farming practices. Other fair trade agreements between retailers and producers have been reached for crops grown in the developing world, including bananas, cane sugar, cocoa, and cotton. While these agreements often increased the price for consumers slightly, they provided a bigger share of revenue to producers and growers.

To reduce poverty for farmers and workers in the periphery, the fair trade movement promoted numerous basic principles:

- Direct trade that will eliminate the intermediary. Transactions directly between the producer and the importer ensure more money to the producer.

- Fair price paid promptly to farmers by importers. Also, the producer must pay workers a fair price.

- Decent conditions are provided for laborers, such as a safe working environment and no use of child or forced labor.

- Environmental sustainability that required farmers to use environmentally safe practices and prohibited genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

- Respect for local culture through shared agricultural techniques with farmers.

The fair trade industry has made significant gains since 1988. More than 1.5 million farmers and workers participate in fair trade and their standard of living has improved, particularly for those in the coffee industry. However, the movement faces the challenge that many consumers feel they cannot afford to pay higher prices for fair trade products.

Government Subsidies and Infrastructure

Governments across the world often provide subsidies, or public financial support, to farmers to safeguard food production. Examples of directly subsidized crops include rice in Japan, wheat and corn in the United States, and soybeans in China. The subsidies are designed to achieve these goals the government believes are in the best interest of the public:

- Protect national security by ensuring a dependable food supply.

- Help farmers by increasing agricultural exports.

- Help consumers by reducing food costs.

Transportation infrastructure is critical to move agricultural products locally, nationally, and globally. Infrastructure includes the roads, bridges, tunnels, ports, electrical grids, sewers, telecommunications, etc. of a country. Global systems of agriculture would not be possible without this infrastructure. Governments, communities, and companies pay to build and maintain a quality infrastructure.

For example, the U.S. government indirectly subsidizes the exports of corn, soybeans, and other agricultural products from the Midwest by spending money to make the Mississippi River navigable for barge traffic. Because water transportation is inexpensive compared to land travel, these products enter the global food supply chain with a lower price than they would have without government support. Because of subsidies, consumers in Mexico City can purchase corn more cheaply from the United States than from rural Mexico. These U.S. policies help people in Mexico City, but at the expense of Mexican farmers.

Similarly, Canada protects its dairy farmers from competition with U.S. dairy producers. This helps Canada’s farmers, but raises costs for Canadian consumers.

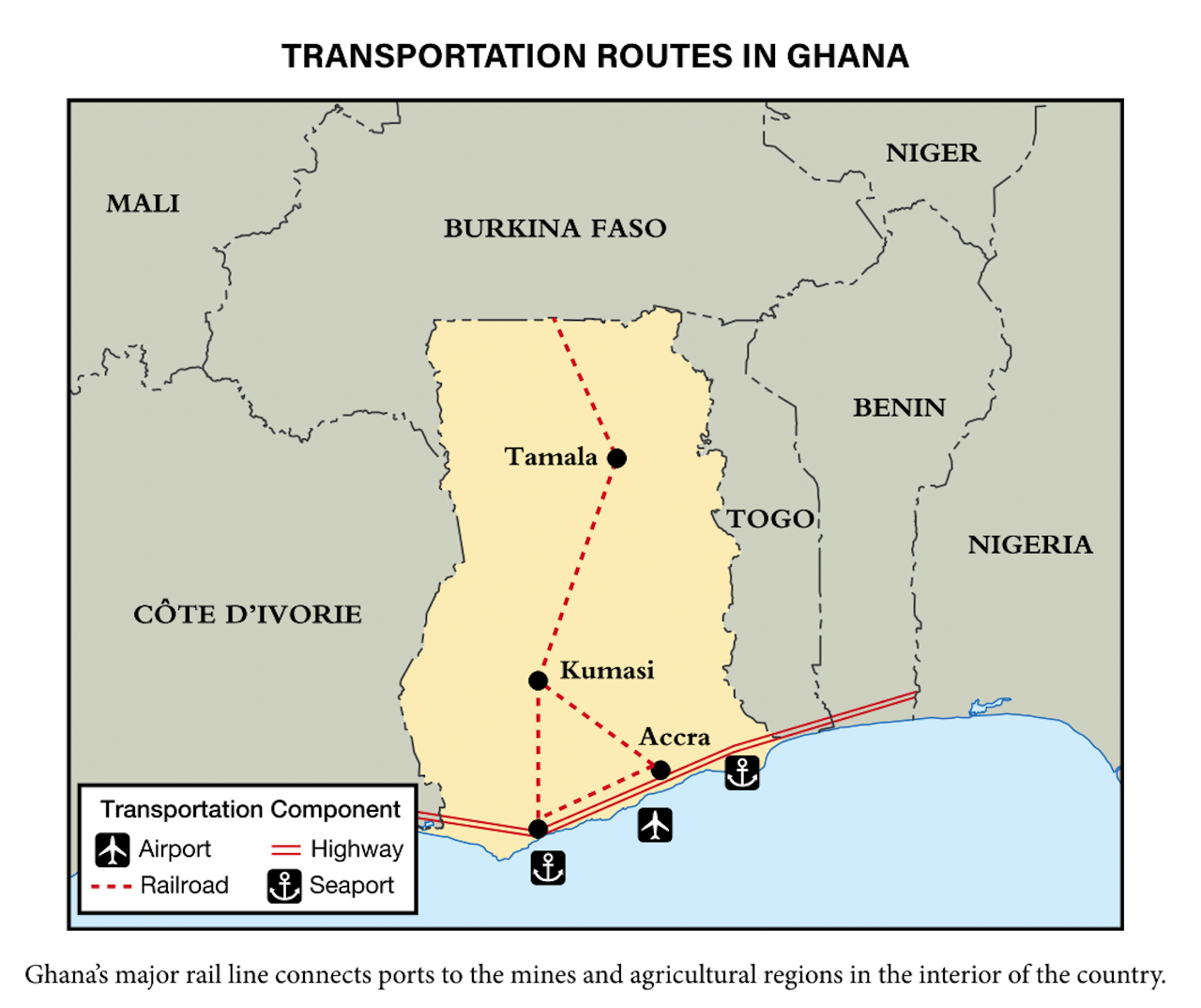

Most infrastructure improvements in developing countries connect resources to ports so goods can be exported. Often, other infrastructure in the country is lacking. As the map of the west African country Ghana on the next page shows, the major rail lines in the country connect the interior, where resources are located, to the ports where they can be exported to the developed world.

Ghana has significant mineral and agricultural resources. However, much of revenue from selling these resources leaves the country. Agricultural products commonly exported from Ghana include cocoa, cotton, coffee, palm oil, and cassava, and gold is the main mineral export. Consequently, there was little money to spend on additional infrastructure, and the population received few benefits from the mineral wealth. See Geographic Perspectives: Ghana as a Case Study in Development (page 327), to learn more about its development strategies.