Von Thunen Model

market

dairy & horticulture

market/truck farming

forrest

grain

ranching & livestock

Economic Concept

bid-rent theory

It is interesting that an almost 200-year-old economic location model, the von Thünen model, is still considered essential by geographers to explain the spatial pattern of agricultural land use. Over the past two centuries there have been many changes to agriculture, as well as transportation, a key component of von Thünen’s model, yet it is still used by geographers today.

Location theory, a key component of economic geography, deals with why people choose certain locations for various types of economic activity factories, stores, restaurants, or agriculture. The von Thünen model, an economic model that suggested a pattern for the types of products that farmers would produce at different positions relative to the market (community) where they sold their goods, is the start of location theory. Since his original work, numerous other geographers have built on his ideas and developed their own location theories and models.

Von Thünen’s Land Use Model Zones

In 1826, Johann von Thünen, a farm owner in Germany, based his rural land use model, sometimes referred to as the Isolated State model, on numerous assumptions:

farming was an economic activity

- farmers were in business to make a profit

- there was one market where farmers sold their products

there was one transportation system - farmers paid transportation costs, which varied with distance

- the market was situated in the center of an isotopic plain, which means flat and featureless with similar fertility and climate throughout

the area beyond the market and farmland (the Isolated State) was wilderness

The von Thünen model is based on the concept that farmers’ decisions regarding what to produce were based largely upon four factors: transportation costs, land costs, intensity of land use, and perishability of the product. Distance from the market impacts the cost of transportation and land. In essence, the land closest to the market is the most valuable and the land farther away decreases in value. Farmers will use land closer to the market more intensely because it is more valuable. The farther goods are transported, the higher the cost. Perishability relates to how well a product can survive transport without spoiling or breaking.

Zones and the Von Thünen Model

In the zone closest to the market, von Thünen suggested that horticulture, a type of agriculture that includes market gardening/truck farming and dairy farming, would occur. Horticulture produces perishable items, and farmers need to get them to market quickly, especially important before trucks and refrigeration. Growing highly perishable crops, such as tomatoes and strawberries, and dairy farming are considered to be intensive forms of agriculture.

Von Thünen’s second zone included forests. Wood was an extremely important resource in 1826, both as building material and as a source of fuel. Von Thünen thought that wood products would be close to the market because they were not only important but heavy, costly, and difficult to transport. Farther from the market, in the third ring, were crops such as wheat and corn. Though valuable, they did not perish as quickly as vegetables and milk and were not as difficult to transport as wood. In addition, corn can be used to feed livestock located in the second and fourth rings.

The final ring was used for grazing of livestock, such as beef cattle. Livestock could be located farther from the market since they have lower transportation costs because farmers can walk them to market. The extensive nature of grain and livestock farming meant that the farms were larger than those located in the inner ring of the model. While there is more farmland available in the larger outer rings, that was not necessarily the reason for these crops to be located there. Grain and livestock farmers could find adequate space in the innermost ring if they were willing to pay enough to acquire the land.

Land Value

The value of land was influenced by its spatial relationship to the market. Because the land in the inner ring was closest to the market, it was more valuable. Therefore, few farmers could afford large amounts of it. Consequently, only farmers who could use a small amount of land intensely and make a profit from it could be successful in the inner ring. They needed to grow high-value crops there, such as fruits and vegetables, in order to make a living.

Grain and Livestock

Land farther from the market was less valuable. Because grain and livestock are less perishable than the crops in the inner ring, the farmers could locate in the area of cheaper land farther from the market and still transport the product to market successfully. Meat is perishable after it is processed, so farmers could avoid spoilage if they walked their livestock to market and had them slaughtered there. This was the common practice when von Thünen developed his model two centuries ago.

Wheat Farms in North Dakota

Recent studies have shown that the distance to the market still greatly influences land prices, even for farmers who raise the same crop. One example from the 21st century is the value of land for North Dakota wheat farmers. For them, the market is often the nearest grain elevator. The elevator owner purchases the grain from many farmers and then resells it to companies in the food processing business. In one study reported by the United States Department of Agriculture, land within 5 miles of a grain elevator was worth double the amount of land approximately 25 miles away. That disparity in land value grew even larger farther than 25 miles away from a grain elevator.

The Bid-Rent Curve

In the case of von Thünen’s model, the bid-rent theory, which refers to the changing value and demand for land as the distance from the market increases, is used to determine what type of agriculture is located in each zone. A graph known as a bid-price curve or bid-rent curve can be used to determine the starting position for each land use relative to the market, as well as where each land use would end.

Each line on the graph reflects the farmers’ willingness to pay for land at various distances from the market. Farmers are willing to pay more for land near the market than for land farther away. However, how much more varies with the types of activities. In a free-market economy where supply and demand, not government policy, determine the outcome of competition for land, the farmer who will have the greatest profit will pay the most at each location to occupy the land. It is where the uppermost line on the graph intersects with the next uppermost line that represents the end of one zone and the start of another.

For example, where the strawberry line intersects the forest line indicates the end of where strawberries will be grown and the beginning of where forests will be found. Where the forest line intersects the wheat line indicates where the forest zone ends and the wheat zone begins.

Application of Von Thünen’s Model

Von Thünen’s model has been valuable in many ways. It has had application far beyond the topic of agriculture. His recognition of the spatial pattern in how farmers made decisions about using resources was the first economic location model. It provided the basis for the industrial location models of Alfred Weber and others who followed.

In addition, even though von Thünen created his model nearly two centuries ago, it continues to be applicable today. The basic insight of the model is still valuable, but like all models, it needs to be adapted to actual conditions and changes in technology.

Non-Isotropic Plains

Von Thünen’s model assumed that land was an isotropic plain–but real land includes rivers, mountains, and other physical features that make it non-isotropic. Von Thünen considered how various landscape situations would alter the shape of each land-use ring and possible impacts on transportation. For example, if a river flowed through the plain, making transportation easier and cheaper, then the zones would stretch out along the river. In addition, some areas have better climates or soil conditions for certain crops. These areas have a comparative advantage, or naturally occurring beneficial conditions, that would prompt farmers to plant crops differently from those predicted by von Thünen’s model.

Multiple Markets

Von Thünen assumed that a farmer had one primary market, but they often have secondary markets as well. A dairy farmer might primarily sell milk to a local dairy. But the farmer might also make and sell cheese, which does not spoil as quickly as milk, in a distant market.

Changes in Transportation

The development of trains, cars, planes, and storage techniques, such as refrigeration, has allowed food to be transported much longer distances without spoiling compared to 1826. As a result, the rings in the model now are wider than originally created by von Thünen. For example, rapidly perishable goods, such as strawberries and milk, can be produced much farther away from the market than in von Thünen’s time. Strawberries and milk are still produced closer to the market than are grains and livestock. It is the size of the rings that has changed, not necessarily the relative position of the rings.

The cut flower market demonstrates the impact of transportation on the application of von Thünen’s model. Cut flowers are very perishable and have to arrive at the market quickly, so they are similar to horticulture and dairy products that the model predicts will be produced nearby and trucked to market. However, many flowers sold in New York City are grown in the Caribbean and South America and flown to market. While air travel costs from these areas are far higher than truck transport from the outskirts of New York, other costs of flower production are much less. Land, labor, and energy costs are so much lower in the Caribbean and South America than in the outskirts of New York City that the savings outweigh the extra transportation costs. Therefore, producers can grow flowers for New York more profitably in the Caribbean than in nearby locations.

Other Changes in Technology

Changes in technology have modified demand for products. Since 1826, wood has been mostly replaced by oil, natural gas, and electricity as fuel for heating homes, so forests as a source of fuel are not particularly important any longer. Forests were also important for producing lumber required for construction of homes and barns. Today, transport trucks can easily and efficiently bring the necessary lumber to the market from distant forests. As a result of both of these changes, forests are rarely located near communities today. Now, forested land at a city’s edge is probably highly valued as a greenbelt, an area of recreational parks or other undeveloped land, rather than a source of fuel or lumber.

Von Thünen Model at a National Scale

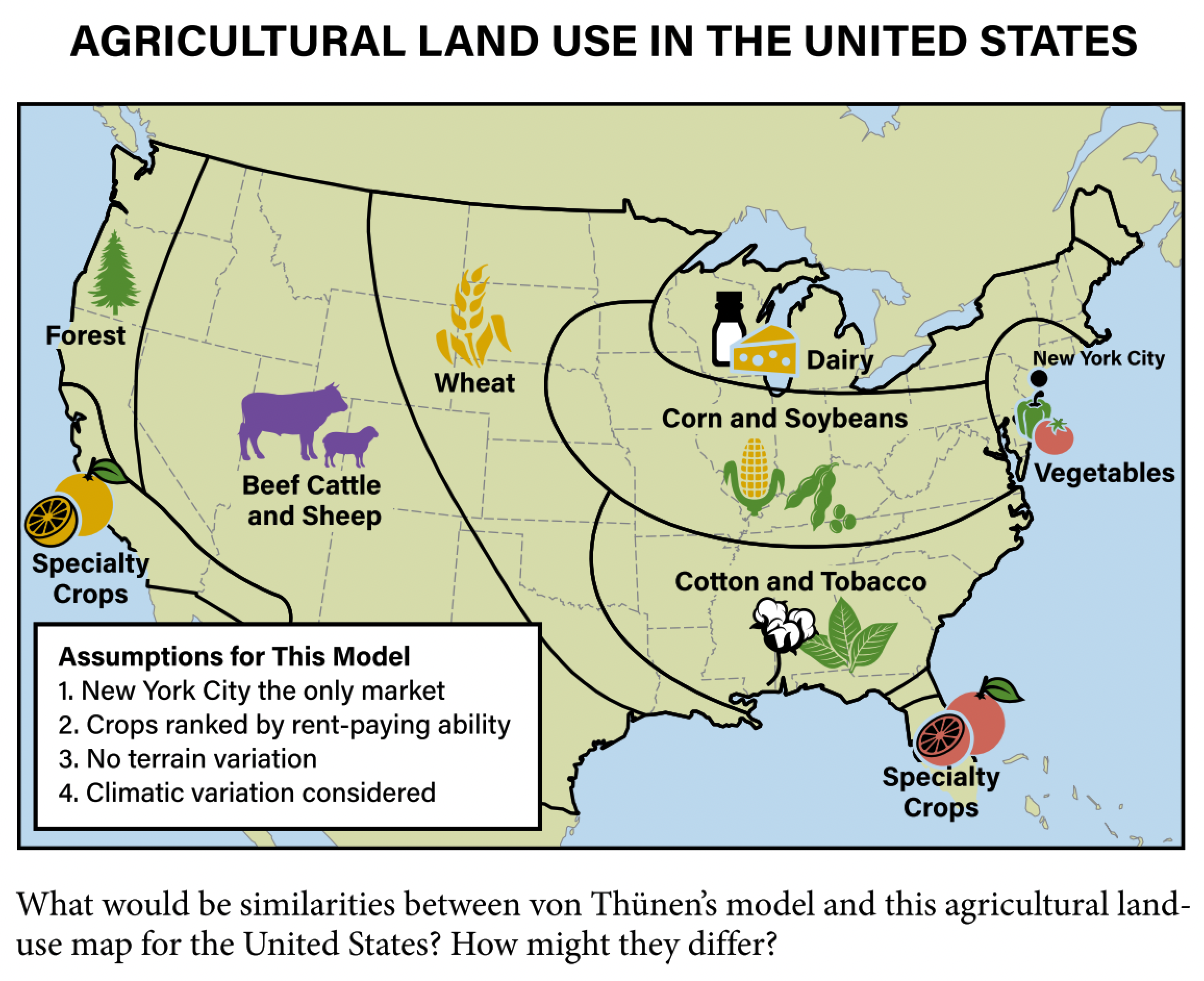

The improved transportation and storage methods have created changes in the use of the von Thünen model today. Since agricultural products are now transported much greater distances to markets, the model can be applied at a much larger scale than von Thünen allowed. The image below illustrates what the general pattern of agricultural land use in the continental United States would look like if the zones were positioned according to the farmer’s rent-paying ability, as suggested by von Thunen. The model assumes that the New York City area is the market, and thus the rings radiate away from there. Also, the map recognizes that there are climatic variations across the country and therefore indicates some pockets of specialty crops as well as distorted rings.

Special Circumstances

No model accounts for every variation that occurs in practice. For example, von Thünen’s model does not fit some areas of specialty farming, such as citrus farming in Florida or the variety of crops grown in the Central Valley of California. Nor does it explain the decisions by developers who speculatively purchase land close to a city and use it for less-intensive agriculture. These developers usually want to invest as little money as possible into the farmland while they wait for the optimal time to build homes, retail space, or commercial structures on it.

Criticisms of Von Thünen’s Model

Many of the criticisms of the model involve the assumptions made by von Thünen.