Boundaries & Borders

demarcated

antecedent

subsequent

consequent

superimposed

geometric

relic

natural

Ocean/Sea Boundaries

L:aw of the Sea

territorial waters

contiguous zone

exclusive economic zone (EEZ)

international waters

The most common type of map used is a reference map, in which physical and cultural features are shown and usually identified. One expects a map, at any scale, to include boundaries that have been clearly delimited. Whether at the local, regional, or national scale, boundaries are an integral part of our lives. Some are invisible to the eye and others are clearly demarcated, yet all serve some political or functional purpose. In essence, any contemporary political boundary can be categorized in one of two ways, physical or cultural. Physical geographic boundaries are natural barriers between areas such as oceans, deserts, and mountains. For example, the Missouri River divides Iowa and Nebraska, and the Himalayan Mountains separate India and China.

By contrast, cultural boundaries divide people according to some cultural division, such as language, religion, or ethnicity. A cultural boundary may exist in the midst of a gradual change over space. For example, in China, cuisine was once divided into two regions: wheat-based in the north and rice-based in the south. However, no exact line has ever divided the two regions sharply. A boundary can be classified as possessing both physical and cultural attributes.

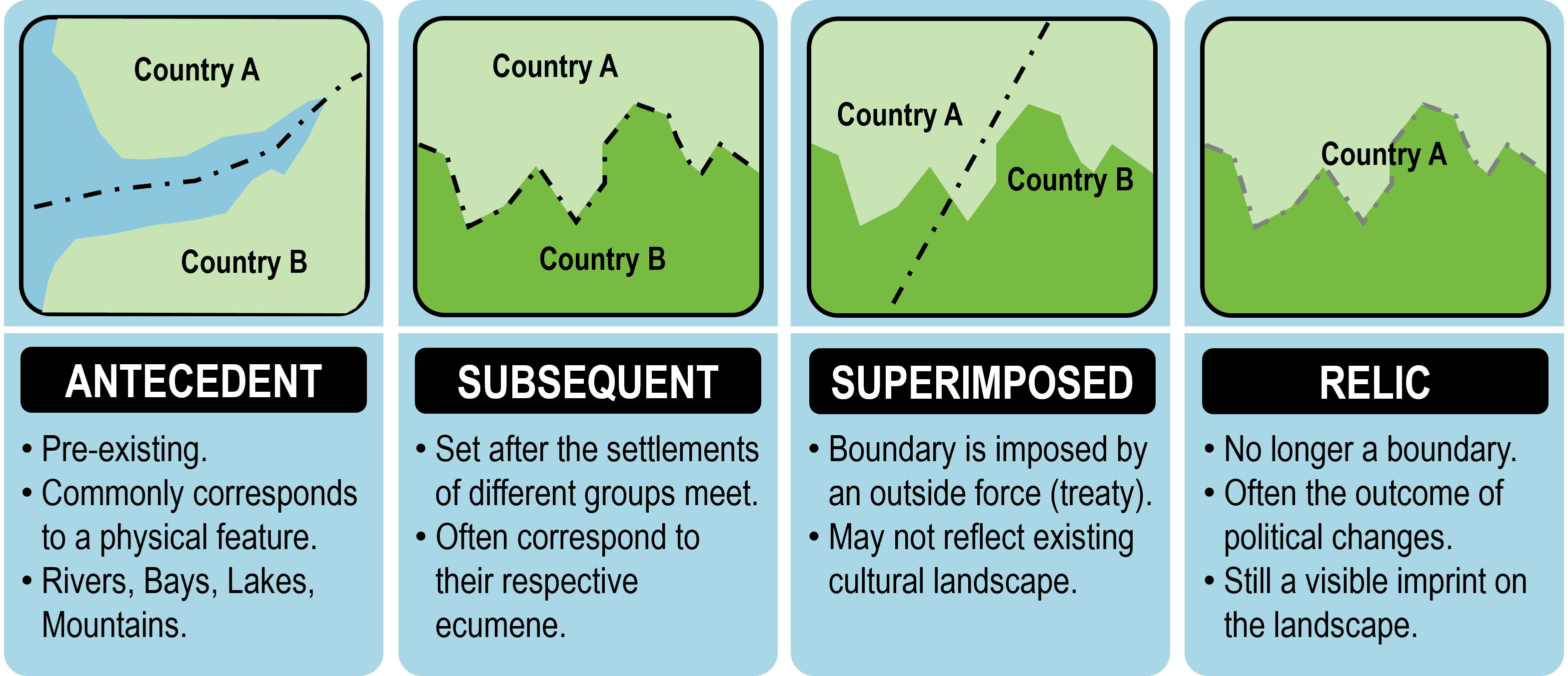

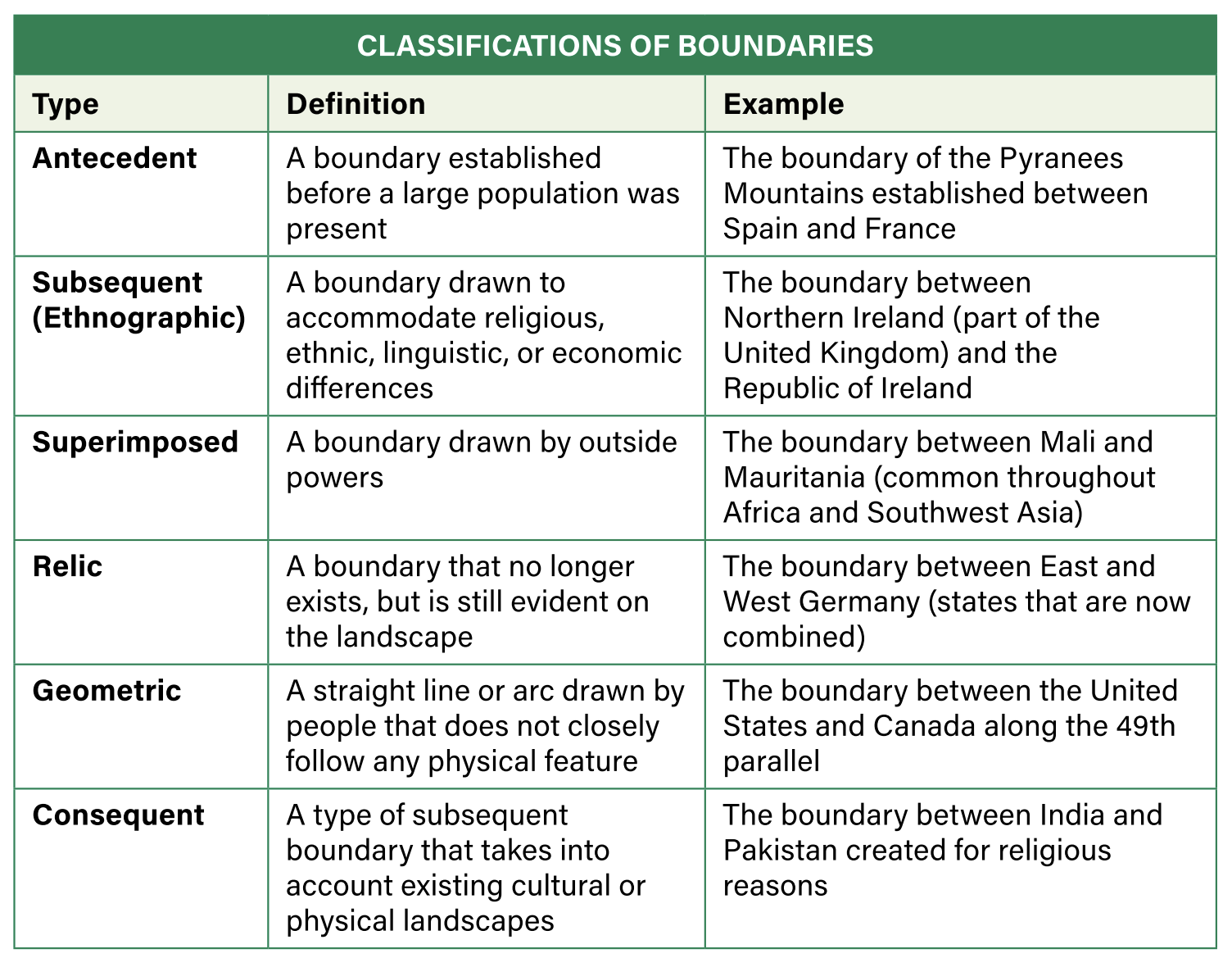

Classifications of Boundaries

While classifying political boundaries as physical or cultural enables us to identify what a border is, geographers have developed a more in-depth classification system that provides greater context on how borders develop over time.

Antecedent Boundary

This type of boundary preceded the development of the cultural landscape. For boundaries, significant physical obstacles-such as oceans or mountains-possess a static aspect in that they feature a relatively unpopulated zone between populated areas. They also possess a kinetic aspect in that they hinder connections and interactions between people in adjacent regions. An example includes the straight-line boundaries for states across the western frontier of the emerging United States. Political boundaries like these were established before a large population was present and remained in place as people increasingly occupied these regions.

Antecedent boundaries are typically based on physical features. Since humans are terrestrial beings and need to live on land for survival, the unpopulated oceans such as the Atlantic and Pacific make for logical antecedent boundaries. The Andes Mountains form the long-reaching eastern boundary of Chile, naturally separating it from Bolivia and Argentina. However, antecedent boundaries that do not present a significant physical obstacle, such as small hills or rivers, tend to make less effective political boundaries. While rivers possess a static benefit in that they maintain an unpopulated zone between populated areas, they tend to facilitate more connections and interactions. Transboundary freshwater sources, such as the Jordan River, have resulted in competing claims among Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine. Just because an antecedent boundary exists, it does not necessarily mean it is effective.

Subsequent Boundary

This boundary is typically created while the cultural landscape is evolving and is subject to change over time. These boundaries are characteristically ethnographic in nature, meaning they are usually related to cultural phenomena. They may be drawn to accommodate ethnic, religious, linguistic, or economic differences among groups. Subsequent boundaries are often altered as a result of non-cultural developments such as governmental negotiations or war. Beginning in the mid-16th century, the monarch of Scotland and England encouraged emigration to Ireland, which was then under English rule. Many Scots and English Protestants settled in the northern region of predominantly Roman Catholic Ireland. Over the years, resentment and violence broke out between the groups over internal borders and political influence in the region. In 1921, Northern Ireland officially became part of the United Kingdom, separating from the southern portion of the island-the Republic of Ireland. A commission was formed to draw the new border based on the religious and political cultural landscape.

Superimposed Boundary

This type of boundary is drawn by outside powers and may have ignored existing cultural patterns. These boundaries often lack conformity to natural features and, therefore, were superimposed on the landscape. Between 1884 and 1885, the Berlin Conference paved the way for colonization of Africa or what Europeans regarded as “effective occupation” of the continent. At the time of the conference, only some coastal areas were colonized by the Europeans and around 80 percent of the continent was under traditional and local control. As a result of the conference, a series of superimposed boundaries were established, initially with little knowledge of the terrain or the cultural borders.

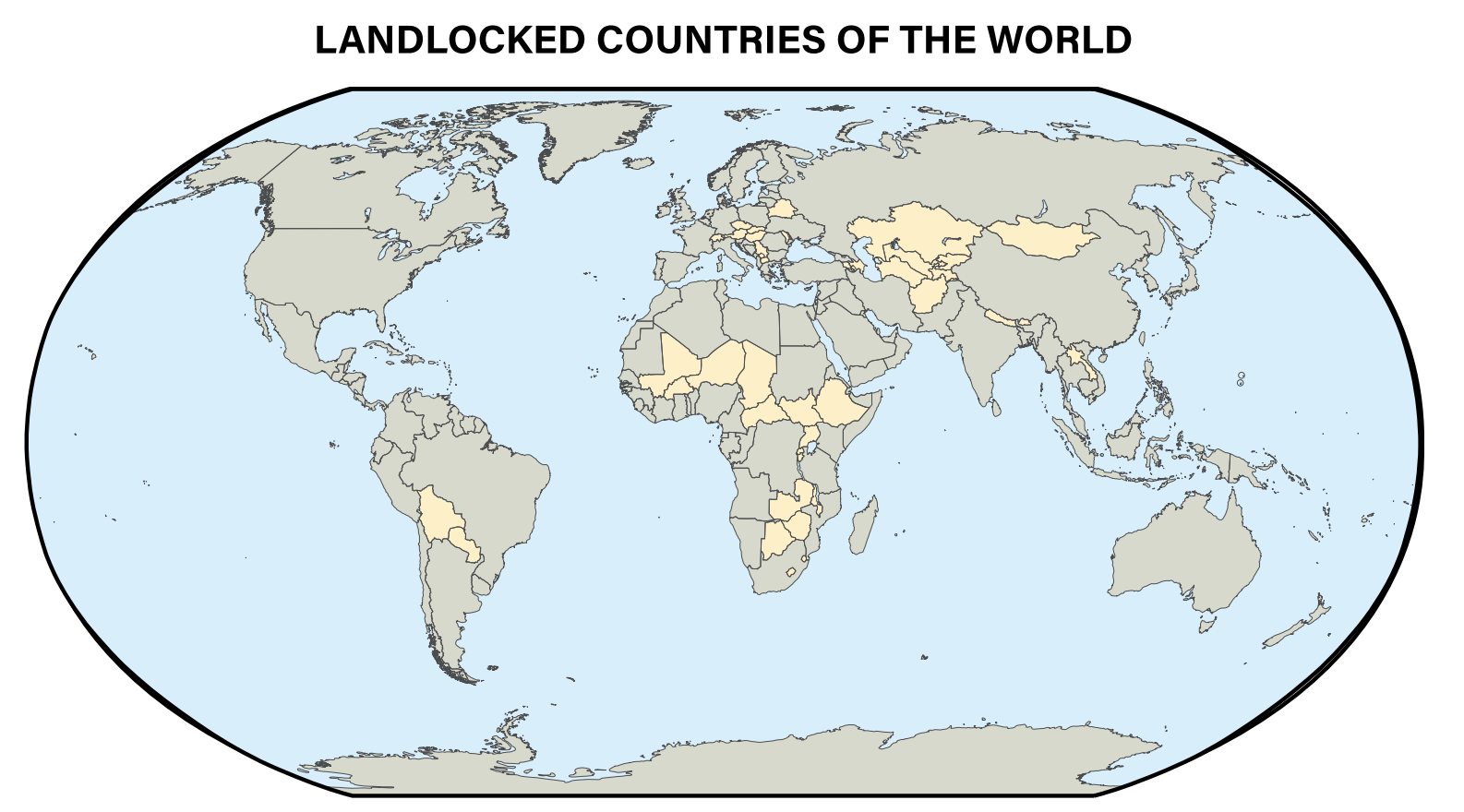

One of the legacies of this “Scramble for Africa” was the creation of around 50 irregularly shaped countries out of the more than 1,000 indigenous cultures that inhabited the continent. Of the 54 current African countries, 17 are landlocked states, or without territory connected to an ocean. The increased cost of importing and exporting goods through neighboring countries presents these states with a perpetual geographic and political disadvantage. Governments of landlocked states are inherently dealing from a weakened position and struggle to effectively negotiate with neighboring countries. While landlocked states, such as Botswana and Rwanda, have recently prospered through effective business growth policies, many landlocked states are among the most impoverished and least-developed countries in the world.

Relic Boundary

This is a boundary that has been abandoned for political purposes, but evidence of it still exists on the landscape. These boundaries are nonfunctional in the political sense but are sometimes preserved for historic purposes. Constructed in 1961, the Berlin Wall that divided East and West Berlin was famously torn down in 1989. Toward the end of the Cold War, East and West Germany reunited, but portions of the Berlin Wall are still upright, maintained as a tourist attraction and symbol of a past age. The Great Wall of China is also a relic boundary, serving no political separation between states, but still very visible on the landscape.

Geometric and Consequent Boundaries

In addition to classifying boundaries by how they were generated, geographers classify boundaries by what they follow. Do they conform to existing cultural boundaries or do they conform to physical features on the landscape?

In contrast to a physical boundary, a geometric boundary is a straight line or arc drawn by people that does not closely follow any physical feature. Historically, many boundaries have fallen upon lines of latitude or longitude, and since the surface of the earth is rounded, extended boundaries may more accurately form arcs. The majority of the boundary between the United States and Canada follows along the 49′ parallel (latitude). After World War II, North and South Korea were divided along the 38″ parallel. Many geometric boundaries are created as internal divisions within a state or territory, such as the political boundaries of Colorado and Wyoming.

A type of subsequent border that takes into account already-existing cultural or physical landscapes is a consequent boundary. A border that is drawn taking into account language, ethnicity, religion, or other cultural traits it is a cultural consequent boundary. Also, these boundaries are created with the cultural landscape as a primary consideration. Political boundaries of this nature would be consequent upon an already-existing cultural phenomenon, such as the partition of the British colony of India in 1947, creating a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan.

Unlike geometric borders, a division that uses already-existing natural features that divide a territory such as rivers, deserts, or mountains is a physical consequent boundary. An example would be the Pyrenees Mountains that run across the northern edge of the Iberian Peninsula, separating Spain from France, and completely surrounding the country of Andorra.

Protection of Boundaries

There are many ways to define boundaries and, furthermore, a single border can possess the attributes of several types. For instance, most superimposed boundaries are geometric. Additionally, there are other border terms that deal with the protective nature of borders and can meet some of the previously discussed classifications.

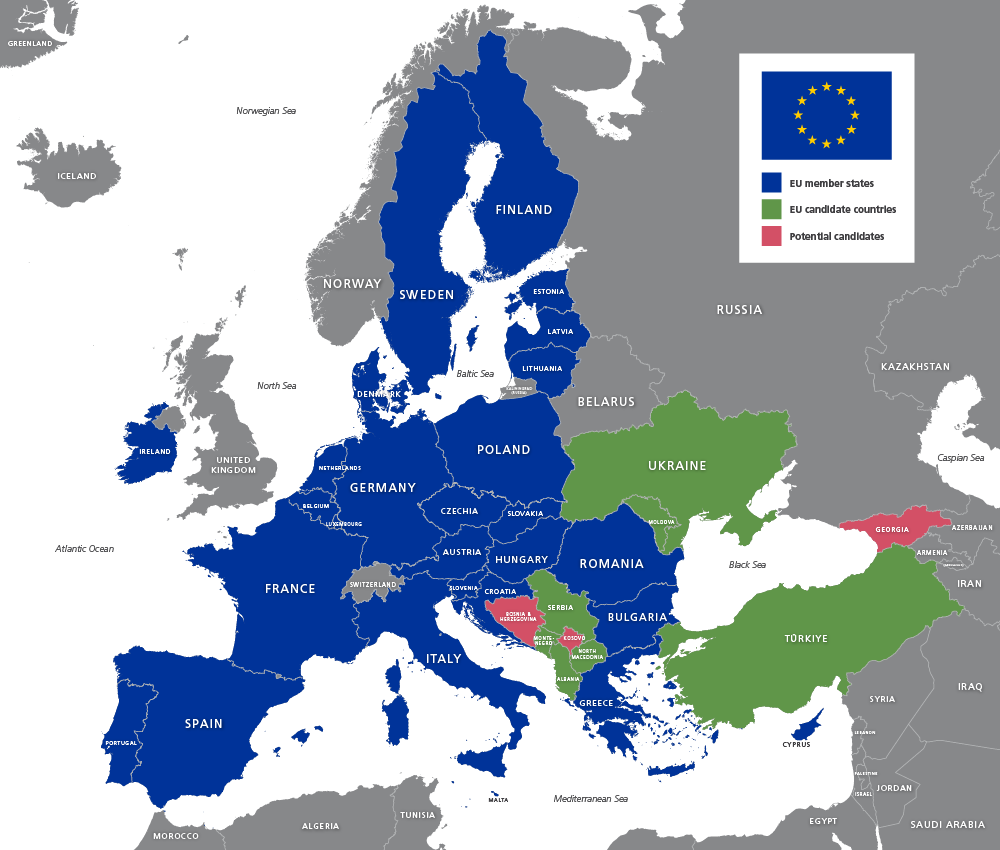

An open boundary is unguarded and people can cross it easily, with little or no political intervention. These borders only occur between countries that have maintained friendly relations with each other over long periods of time. Most states within the European Union (EU) fit this category.

A militarized boundary is one that is heavily guarded and discourages crossing. While many of these borders only have a limited military presence, others are fortified, using a constructed barrier to prevent the flow of people. In 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, there were 15 border walls in the entire world. As of 2020, there were five times that number.

One of the most well-known barriers in the world today is the Korean DMZ (demilitarized zone) that separates North and South Korea. The 160-mile long, 2.5-mile wide strip of land serves as a buffer zone between the rival states. It was established in 1953 after the cease-fire that ended the Korean War. In 2020, the United States had more than 28,000 troops stationed in South Korea along the DMZ, a deterrent to any potential aggression by North Korea. The DMZ almost completely blocks the flow of trade and people.

The Function of Political Boundaries

When most people think of a boundary, they focus on what is represented on the surface of the earth. However, boundaries are actually vertical planes that cut through the subsoil below, rise into the airspace above, and even extend into outer space.

Political borders serve a vital function as dividing lines between countries, states, provinces, territories, counties, cities, towns, villages, and municipalities. Political borders also exist to separate bodies of water, especially those that possess multiple claims to the same areas. To fully comprehend the complex interactions between political entities, an understanding is needed of boundary formations and functions, as well as why disputes erupt around them.

International and Internal Boundaries

In theory, boundaries of all kinds exist to add clarity. Boundaries signal where one political entity begins and another ends. This helps people know what territory is theirs to administer and what belongs to another country. But when neighbors disagree on where the line that separates them should be, boundaries become the subject of conflict. Throughout history, uncertain boundaries have been a frequent cause of bloodshed and war.

Formation of Boundaries

Boundaries represent changes in the use of space from one political entity to another. Crossing a boundary implies that some rules, expectations, or behaviors change. When moving across a formal political boundary, these rules are called laws. Boundaries can be identified in various ways:

- A defined boundary is established by a legal document, such as a treaty, that divides one entity from another (invisible line). The entity could range from a country-in which points of latitude and longitude are specified- to a single plot of real estate- in which points in the landscape are described.

- A delimited boundary is drawn on a map by a cartographer to show the limits of a space.

- A demarcated boundary is one identified by physical objects placed on the landscape. The demarcation may be as simple as a sign or as complex as a set of fences and walls.

Some very influential boundaries are not set formally. Informal boundaries include ones marking the spheres of influence by powerful countries at the regional scale, such as the Monroe Doctrine. In 1821, President James Monroe warned Europeans that the United States would oppose any attempts they made to expand their influence in the Americas. Informal boundaries also exist at the local level, such as those dividing the neighborhoods controlled by various street gangs.

International Boundary Disputes

As the number of states has increased over the last century, so too have international boundary disputes. There are four main categories of boundary disputes: definitional, locational (territorial), operational (function), and allocational (resource).

Definitional Dispute

A definitional boundary dispute occurs when two or more parties disagree over how to interpret the legal documents or maps that identify the boundary. These types of disputes often occur with antecedent boundaries. One example is the boundary between Chile and Argentina. The elevated crests of the Andes Mountains serve as the boundary, but since most of the southern lands were neither settled nor accurately mapped, control of this territory lies in dispute.

Locational Dispute

Boundary disputes that center on where a boundary should be, how it is delimited (mapped), or demarcated are known as locational boundary disputes. These disputes are also called territorial disputes because of the fundamental question of who possesses the land. An example of a locational dispute was the post-World War I boundary between Germany and Poland. Germans disputed the location because it controlled the land prior to the war, but the border drawn after the war left many ethnically German people on the Polish side. This led to irredentism, a type of expansionism when one country seeks to annex territory where it has cultural ties to part of the population or historical claims to the land. Many groups are divided between countries by a border. When this occurs a desire to unify their nation is a common national goal and can lead to irredentist feelings but not always action.

Operational & Functional Dispute

An operational boundary dispute, or functional dispute, centers not on where a boundary is but how it functions. Disagreements can arise related to trade, transportation, or migration. As refugees fled Syria and attempted to enter Europe during the 2011 civil war, Europeans viewed their national boundaries differently. Refugees began migrating from southern Europe to the interior seeking safe haven. Interior countries of Europe often viewed the countries to the south and east as responsible for stopping migrants, while others felt the boundaries should stay open in order to help the refugees. Additional operational boundaries can occur with rivers and choke points that serve as boundaries. Questions related to who controls the transportation and shipping on a river or choke point can cause disagreements.

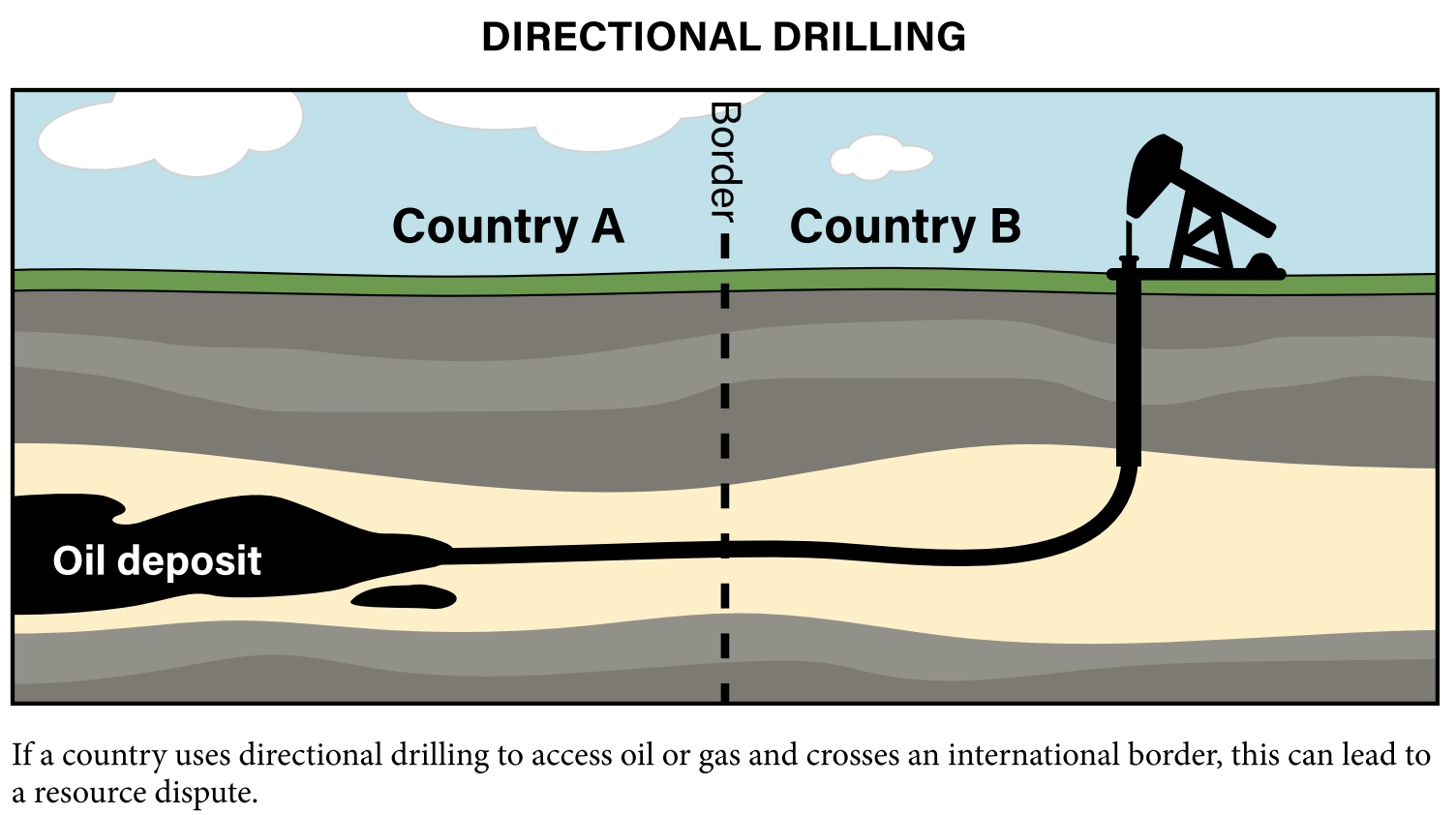

Allocational Dispute

When a boundary separates natural resources that may be used by both countries, it is referred to as an allocational boundary dispute, or resource dispute. When it comes to natural resources, boundaries serve as vertical planes that extend both up into the sky and down into the earth. The extraction of subterranean resources extending on both sides of the boundary may become complicated and lead to conflict. In 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait because it claimed that the Kuwaitis were drilling too many wells using directional drilling, thus breaking the vertical plane and extracting oil on the Iraqi side of the boundary. Other resources that are often at the center of disputes include fresh water, minerals, and fishing rights.

Demarcation and Functions of Boundaries

How a border is labeled on the physical landscape such as with a fence, wall, stones or signs is called demarcation. This process can indicate the type of relationship that exists between countries and be a clue to how the border functions. Many borders in the world are not demarcated at all because they are in vast wilderness areas with no one living there or the relationships between the two states is cordial, open, and peaceful. Additionally, most boundaries are not demarcated as the process tends to be protracted and expensive.

How a boundary will be maintained, how it will function, and what goods and people will be allowed to cross are important aspects of an administered boundary. As relations change between countries, and also between entities within a state, the means by which a boundary is demarcated and administered may change significantly.

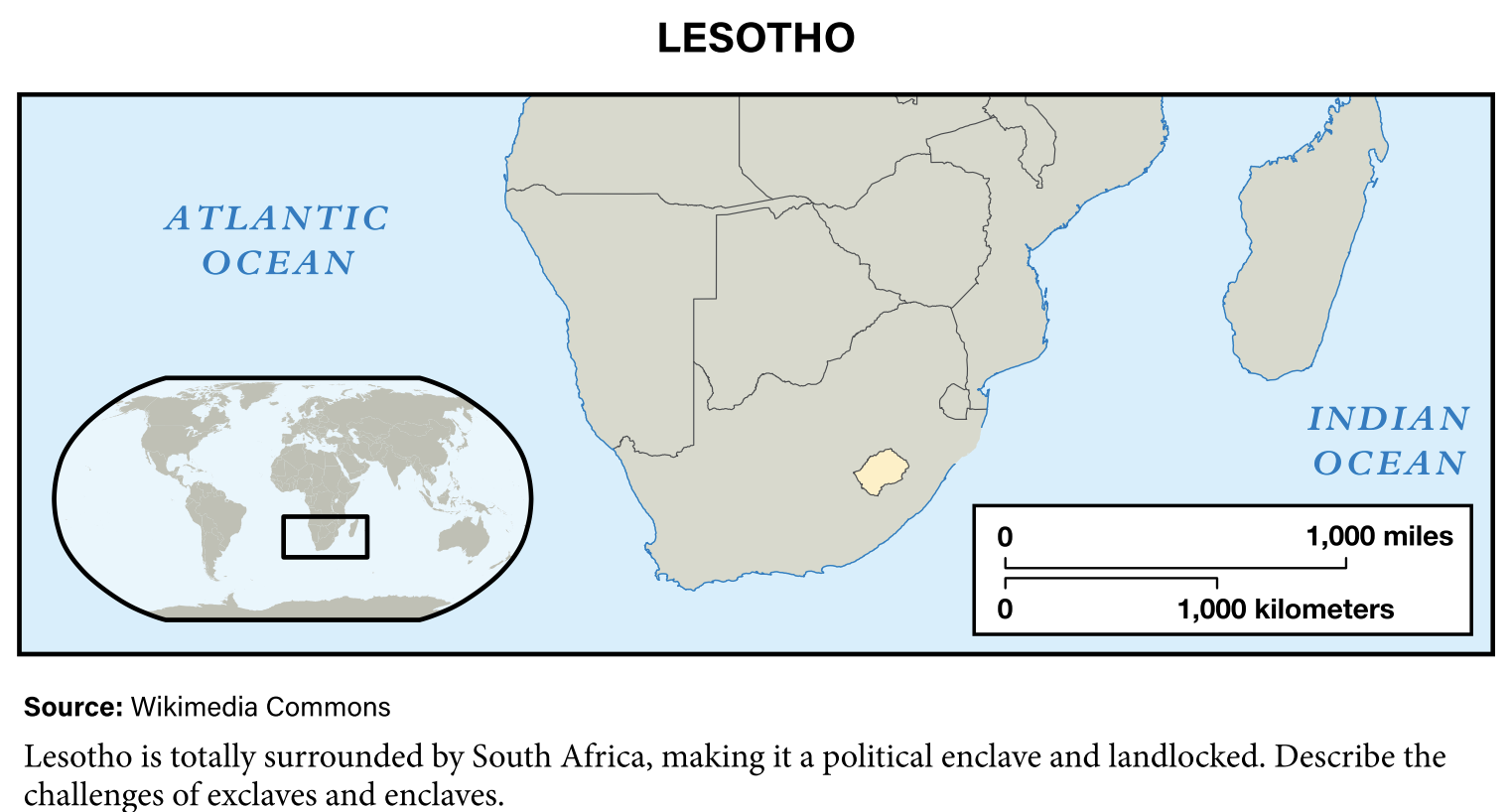

Unique Boundaries: Exclaves and Enclaves

As a result of migration, trade deals, devolution, conflicts, and other reasons, pockets of isolated national groups sometimes find themselves separated from their homeland. Exclaves are territories that are part of a state, yet geographically separated from the main state by one or more countries. For example, Alaska is separated from the lower 48 United States by Canada.

Indian reservations within the United States may be considered enclaves as they possess tribal sovereignty and are recognized as independent nations.

The Law of the Sea

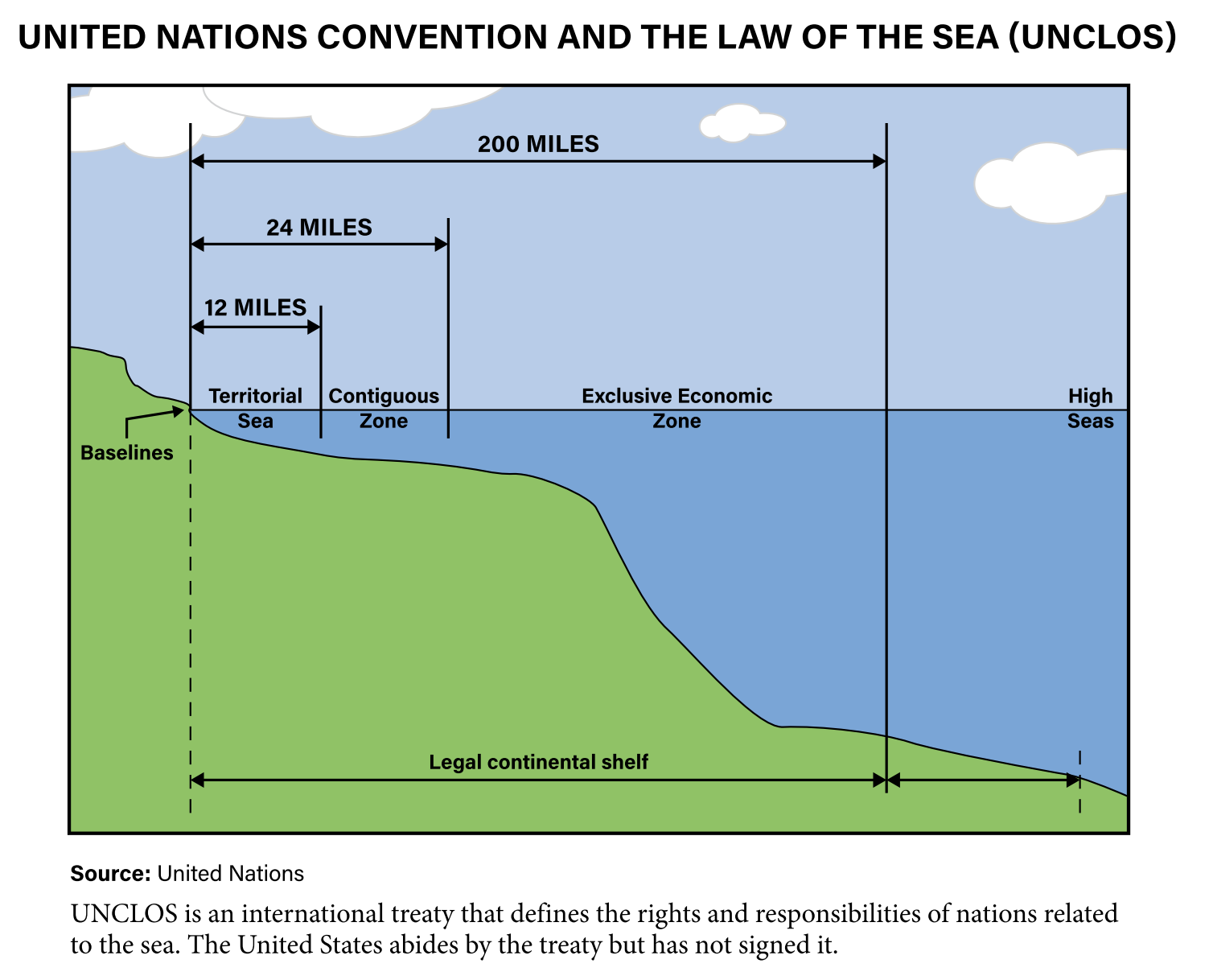

Countries generally agree that a vertical plane extends through borders, defining space above and below the land. However, how far horizontally out into the ocean should a country’s influence spread? Conflicts over the use of the ocean have been common in modern history. Only in the last half of the 20th century were water boundaries addressed systematically. Between 1973 and 1982, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea was signed by more than 150 countries. It defined four zones:

- Territorial sea: This area extends up to 12 nautical miles of sovereignty where commercial vessels may pass, but noncommercial vessels may be challenged. A nautical mile is equal to 1.15 land-measured miles.

- Contiguous zone: Coastal states have limited sovereignty for up to 24 nautical miles where they can enforce laws on customs, immigration, and sanitation.

- Exclusive economic zone (EEZ): Coastal states can explore, extract minerals, and manage natural resources up to 200 nautical miles.

- High seas: Water beyond any country’s EEZ that is open to all states.

If two coastal states share a waterway and are less than 24 nautical miles apart, then the distance between the two coasts is divided by half. For example, if only 20 miles of water separated two countries, then each would be entitled to 10 miles of territorial sea.

The Value of Islands

States that have islands have been granted vast areas of space. For example, if a country’s farthest island extends several hundred miles from the mainland, then the EEZ of that outward island extends that country’s claims by another 200 miles. For example, near Alaska, where islands extend far out in the Bering Sea, the EEZ of the United States is huge.

The United States’ EEZ covers more area than any other country -3.4 million square miles. That is almost as much as the total land area of the United States (3.8 million square miles).

The 200-mile EEZ is very valuable economically to the many small island developing states (SIDS) in the world’s oceans. SIDS control nearly 30 percent of all oceans and seas and their EEZs are much larger than their landmass.

Tuvalu’s EEZ in the South Pacific is 27,000 times the size of its land, but its EEZ contains valuable minerals, natural gas and fishing stocks, and the prospect of tourism. These new economic opportunities based on the ocean for SIDS have been given the term blue economy.

Arctic Opportunities

The Arctic Ocean is a region where challenges are being made related to land, deep water natural resources, and sea passages for ships. As the ice in the Arctic Ocean melts, countries in the region such as Russia, Canada, the United States, Norway, and Denmark see new economic opportunities in the region.

South China Sea

In 2011, a territorial dispute in the South China Sea emerged related to the Spratly Islands, a series of small islands and coral reefs.

The region is a rich fishing ground, important trade route, and a source of potential natural gas and oil reserves. China, Vietnam, and other neighboring countries are in the midst of a tension-filled dispute. China has made claims to large parts of the sea and has built artificial islands on the reef to solidify its territorial claims and expand its 200-mile EEZ.