Where do prices come from?

supply curve

demand curve

surplus

shortage

equilibrium price/quantity

external factors that affect supply/price

Supply & Demand Vocab

markets

labor market

price signals

Every Saturday morning, a local farmer’s market springs to life. Vendors set up their stalls, offering everything from fresh vegetables to homemade bread. At one stall, ripe tomatoes are priced at $2 per pound, and customers line up eagerly to buy them. But at another stall, a farmer selling the same tomatoes for $4 per pound struggles to attract buyers. By the end of the day, the first farmer has sold out, while the second has unsold produce. Why the difference? It’s not random—it’s the invisible forces of supply and demand at work, shaping the prices of goods right before our eyes.

Just as prices for goods like tomatoes are influenced by these forces, so too are wages in the labor market. Consider a coffee shop looking to hire baristas. If the shop offers too low a wage, few workers will apply, and the positions will remain unfilled. On the other hand, if the shop offers a generous wage, it might attract plenty of applicants but strain its budget. Somewhere in between lies a wage that balances the supply of workers with the business’s ability to pay—a reflection of how markets operate to find equilibrium.

The prices of goods and services, as well as wages for workers, are not random guesses but follow predictable patterns rooted in economic principles. Supply and demand curves interact to determine equilibrium prices, and external factors—such as the weather for farmers or the minimum wage laws for employers—can shift these patterns. Surpluses and shortages emerge when prices deviate from equilibrium, creating adjustments that steer markets back on course.

This chapter will delve into how prices and wages are determined in markets, exploring the roles of supply and demand, the importance of equilibrium, and the impact of external factors. By understanding these dynamics, we can better grasp how the economy functions, from the price of everyday goods to the wages that sustain our livelihoods.

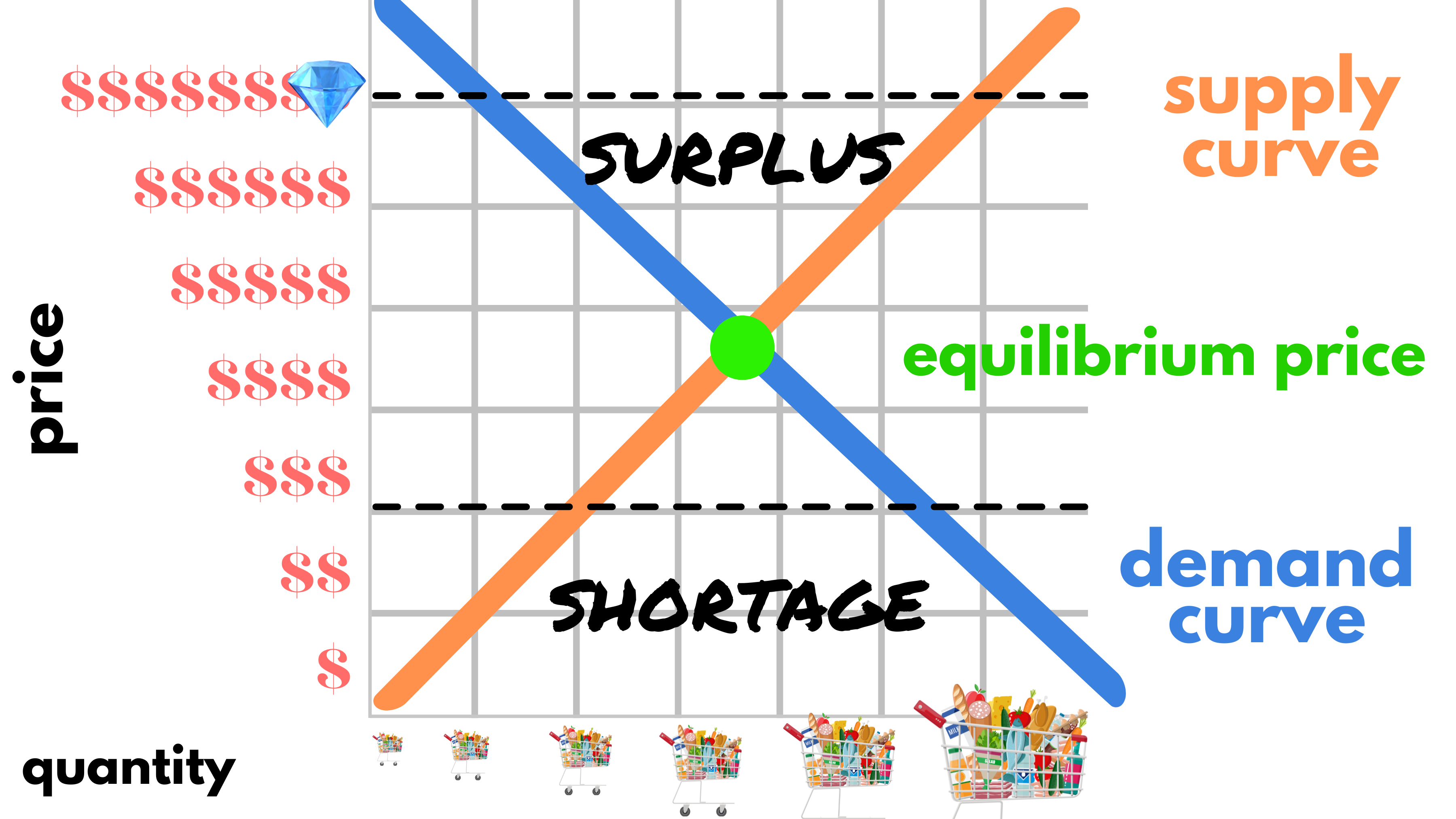

Supply Curve, Demand Curve, Surplus, Shortage, and Price Equilibrium

The prices of goods and services are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, two fundamental concepts in economics that are often visualized using curves on a graph.

The Supply Curve

The supply curve represents the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity that producers are willing and able to sell. Generally, the supply curve slopes upward: as prices increase, producers are more willing to supply more of the good because higher prices lead to higher profits. For example, if the price of apples rises, apple farmers might work harder to harvest more apples or plant more trees in the future to take advantage of the higher profits.

The Demand Curve

The demand curve shows the relationship between the price of a good or service and the quantity that consumers are willing and able to purchase. Unlike the supply curve, the demand curve slopes downward: as prices decrease, consumers are willing to buy more of the good because it becomes more affordable. For instance, if movie tickets drop from $12 to $8, more people may decide to go to the theater because it fits better within their budget.

Surplus and Shortage

When supply and demand are out of balance, the market experiences either a surplus or a shortage. A surplus occurs when the price is too high, causing producers to supply more than consumers are willing to buy. For example, if a bakery charges $5 for a loaf of bread but customers are only willing to pay $3, the bakery might end up with unsold loaves. In contrast, a shortage happens when the price is too low, encouraging more consumers to buy while discouraging producers from supplying enough. If bread were priced at $1, customers might buy out all the loaves quickly, leaving some empty-handed.

Price Equilibrium

The point where the supply curve and demand curve intersect is called the price equilibrium. This is the price at which the quantity of goods producers are willing to supply equals the quantity consumers are willing to buy. At this price, the market is in balance—there is no surplus or shortage. For example, if the equilibrium price for bread is $3, the bakery will produce exactly the amount of bread that customers are willing to buy at that price.

How Prices Adjust

Prices naturally adjust toward equilibrium in response to surpluses or shortages. If a surplus occurs, producers might lower prices to encourage more purchases. Conversely, if a shortage happens, prices tend to rise as consumers compete for the limited goods. This self-correcting mechanism ensures that markets remain functional and efficient over time.

By understanding the interaction between supply and demand curves, surpluses, shortages, and price equilibrium, we can see how prices for goods and services are not arbitrary but are shaped by predictable economic forces that balance the needs of both producers and consumers.

External Factors That Affect Supply, Price, and Demand

While supply and demand largely determine prices for goods and services, external factors often disrupt these patterns. These factors can significantly affect supply chains, alter consumer behavior, and shift prices, sometimes creating challenges and other times opportunities.

Disruptions in Supply Chains

One of the most striking examples of external factors affecting supply was the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, global supply chains faced massive disruptions. Factories shut down, transportation networks were delayed, and raw materials became scarce. This reduction in supply caused the prices of many goods to spike. For example, the shortage of semiconductor chips—a critical component in everything from cars to smartphones—led to higher prices for vehicles and electronics. Even basic goods like toilet paper and cleaning supplies experienced shortages as demand surged while supply struggled to keep up.

Seasonal and Holiday Demand

Holidays like Christmas significantly influence consumer behavior, leading to a surge in demand for certain goods and services. Retailers anticipate higher demand for toys, electronics, and holiday decorations during the Christmas season, often resulting in temporary price increases. For instance, the price of Christmas trees tends to rise in December because of the seasonal spike in demand, even though the supply is relatively fixed. Similarly, products like turkeys around Thanksgiving and chocolates during Valentine’s Day see price changes driven by holiday-specific demand.

Government Policies and Regulations

Government policies can also act as external factors. For example, tariffs or trade restrictions can increase the cost of imported goods, affecting both supply and price. During the pandemic, governments around the world imposed restrictions on exports of medical supplies like masks and gloves, creating supply shortages and driving up prices in international markets. Additionally, changes to minimum wage laws can directly influence the labor costs for businesses, which may then pass on higher costs to consumers in the form of increased prices.

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters such as hurricanes, wildfires, or droughts can disrupt supply chains and reduce the availability of key goods. A drought in California, for example, can lower the supply of fruits and vegetables, driving up prices across the country. Similarly, Hurricane Katrina in 2005 disrupted oil production and refining in the Gulf of Mexico, leading to a spike in gasoline prices nationwide.

Technological Advances

On the flip side, external factors can also reduce costs or increase supply. Technological advancements often improve production efficiency or reduce costs. For example, the development of renewable energy technology has decreased the cost of solar panels over time, making them more affordable for consumers and increasing demand.

Cultural and Social Trends

Trends and consumer preferences can also shift demand. For instance, growing awareness about environmental sustainability has increased demand for electric vehicles and plant-based foods, driving up their prices and encouraging more suppliers to enter these markets.

Unpredictable Shocks

Unexpected events, like a war or geopolitical crisis, can drastically affect supply and demand. For example, the conflict in Ukraine disrupted global wheat and energy supplies, driving up prices for bread and fuel worldwide. These shocks ripple through markets, often in ways that are difficult to predict or control.

How External Factors Shape Markets

External factors, whether seasonal, geopolitical, or natural, remind us that markets are not closed systems. The interplay between predictable forces like supply and demand and unpredictable external shocks creates the dynamic environment that businesses and consumers navigate daily. By understanding these influences, we can better anticipate price changes and adapt to market conditions, whether it’s during a holiday shopping spree or a global crisis.

Price Signals: What Prices Communicate in a Market

Price signals are the messages that prices send to consumers and producers about the relative value of goods and services. They act as indicators of supply and demand, guiding decisions in a market economy without the need for direct communication between buyers and sellers. Price signals play a critical role in efficiently allocating resources and balancing markets.

How Price Signals Work

When the price of a good rises, it signals to producers that the good is in high demand or that its supply is limited. This encourages producers to make more of the good to capitalize on potential profits. On the consumer side, higher prices signal scarcity, prompting buyers to either purchase less of the good or look for substitutes. Conversely, when prices drop, the signal to producers is to slow down production, while consumers are encouraged to buy more because the good is more affordable.

Examples of Price Signals in Action

- The Gasoline Market

When global oil supplies are disrupted by events like geopolitical conflicts or natural disasters, the price of gasoline often rises. This price increase signals to consumers to conserve fuel or seek alternatives, such as public transportation. At the same time, the higher price incentivizes oil companies to ramp up production or explore alternative energy sources. - Holiday Pricing

During the Christmas season, the price of popular toys often increases due to high demand. This price signal encourages manufacturers to produce more toys to meet the seasonal demand. For consumers, the higher prices might lead some to delay purchases or consider alternative gifts. - Housing Market

If home prices in a particular area rise sharply, it signals to developers that there is high demand for housing. This encourages them to build more homes in that area. For buyers, rising prices may push some to look for houses in more affordable locations or rent instead.

The Role of Flexibility in Price Signals

Price signals are most effective in markets where prices can freely adjust based on supply and demand. In some cases, however, external factors like government-imposed price controls (e.g., rent ceilings or minimum wages) can distort price signals. For example, a price cap on gasoline might lead to shortages because the artificially low price discourages producers from supplying enough fuel.

Why Price Signals Matter

Price signals allow markets to self-regulate, coordinating production and consumption without the need for central planning. They ensure that scarce resources are directed toward their most valued uses. For example, if the price of wheat rises due to a poor harvest, farmers are incentivized to plant more wheat, while consumers might shift to alternative grains like rice or barley. This dynamic response helps stabilize the market over time.

In essence, price signals are the economy’s way of communicating critical information. By observing and responding to these signals, producers and consumers make decisions that collectively drive the efficient functioning of markets.

How the Labor Market Operates to Set Wages

The labor market operates much like other markets: wages are determined by the interaction of supply and demand, but instead of goods and services, the “product” being exchanged is labor. Employers represent the demand for labor, while workers represent the supply. Wages are the “price” paid for this labor, and they fluctuate based on various factors within and outside the market.

Demand for Labor

The demand for labor comes from employers who need workers to produce goods or provide services. This demand depends on:

- Productivity: Workers who can produce more or create higher-value output are in greater demand and command higher wages. For example, a software engineer might earn more than a retail cashier because their skills generate more revenue for the company.

- Economic Conditions: During economic growth, businesses often expand and hire more workers, increasing demand for labor. Conversely, during a recession, companies may cut jobs, reducing demand.

- Industry and Skill Requirements: Some industries, like healthcare or technology, have higher demand for specialized skills, often leading to higher wages in those fields.

Supply of Labor

The supply of labor comes from individuals willing and able to work. Factors influencing the supply of labor include:

- Population and Demographics: A larger working-age population increases the labor supply, while an aging population may reduce it.

- Education and Skills: Workers with more education or specialized training are often in shorter supply, which can drive up wages in certain professions.

- Preferences and Incentives: Workers may choose jobs based on wages, working conditions, or personal preferences, affecting the availability of labor in different sectors.

Equilibrium Wage

Wages are determined at the point where the supply of labor matches the demand for labor, called the equilibrium wage. At this wage:

- Employers can hire the number of workers they need without creating a surplus (too many job seekers) or a shortage (too few workers).

- Workers find jobs that match their skills and compensation expectations.

For example, in the fast-food industry, if wages are set too low, the supply of workers may shrink as potential employees seek better-paying jobs elsewhere, leading to unfilled positions. If wages are too high, businesses may hire fewer workers to control costs or replace jobs with automation.

External Factors Affecting Wages

Several external factors can influence the labor market and wages:

- Minimum Wage Laws: Government-mandated minimum wages set a floor below which employers cannot pay workers, ensuring a basic standard of living but potentially creating surpluses if employers reduce hiring.

- Union Bargaining: Unions negotiate collectively for higher wages and better benefits, often raising wages above the equilibrium level in specific industries.

- Globalization: Access to cheaper labor markets abroad can suppress wages in domestic markets as companies outsource jobs or face competition from foreign firms.

- Technology: Advances in technology can increase productivity, raising wages for skilled workers but potentially reducing demand for less-skilled labor.

Why Wages Vary Across Jobs

Wages vary widely across industries, regions, and roles due to differences in demand, supply, and external factors. High-demand jobs with limited supply, such as medical specialists or data scientists, command higher wages. Conversely, jobs with abundant labor supply and lower skill requirements, like entry-level retail positions, typically offer lower wages.

Ultimately, the labor market’s operation ensures that wages reflect the value of labor in specific contexts. When labor markets function efficiently, they allocate workers to roles where their skills and contributions are most valued, benefiting both employers and employees. However, inefficiencies like discrimination, information gaps, or economic shocks can distort this balance, requiring additional policies or interventions to correct them.