Historical Innovations

enclosure movement

crop rotation

irrigation

cotton gin

seed plow

grain elevator

Effects

population growth & DTM

rural to urban migration

economic development

Contemporary Innovations

fertilizers

pesticides

herbicides

genetically modified organisms

factory farming

Effects

food supply

hunger & food afforability

environment

Agricultural Innovations Shark Tank

Agricultural Innovation Options:

- The Enclosure Movement & Crop Rotation

- The Steel Plow & The Seed Drill

- The Cotton Gin and Irrigation

- Chemical Pesticides and Herbicides

- Fertilizers

- Genetically Modified Crops

- Industrial-Scale Farming

- Meat Alternatives

General Requirements:

- What is the innovation?

- How does it work/what does it do?

- How does it save labor/increase yields?

- What is it’s impact on population growth and proving Malthus wrong?

Agriculture underwent a wide-ranging overhaul beginning in the mid-18th century, and the changes have not slowed since. Technological advances of the Industrial Revolution benefited farmers with dramatically better yields and productivity. As a result, the world moved out of the First Agricultural Revolution and into a series of new agricultural revolutions based on innovation and science to meet an increased global demand for food:

- The Second Agricultural Revolution, which began in the 1700s, used the advances of the Industrial Revolution to increase food supplies and support population growth. Agriculture benefited from mechanization and improved knowledge of fertilizers, soils, and selective breeding practices for plants and animals.

- The Third Agricultural Revolution, which began in the 1960s, included the Green Revolution and an agribusiness model that controlled the development, planting, processing, and selling of food products.

Impact of the Second Agricultural Revolution

The Second Agricultural Revolution involved the mechanization of agricultural production, advances in transportation, development of large-scale irrigation, and changes to consumption patterns of agricultural goods. Innovations, such as the steel plow and mechanized harvesting, greatly increased food production, particularly in Europe and the United States. The impact of the Second Agricultural Revolution, coupled with discoveries to better preserve food, increased the food supply, especially to countries that participated in global trade networks. The net result was that more people had access to a greater variety of food, which increased life expectancies.

Property Rights and Farming Advances

Paralleling changes in technology were changes in the law. The Enclosure Acts were a series of laws enacted by the British government that enabled landowners to purchase and enclose land for their own use. This land had previously been common land shared by peasant farmers. Similar enclosure movements occurred throughout Europe that allowed for larger farms, more efficient production, and crops sold for profit rather than personal consumption.

However, the enclosures came at a high cost. Many farmers were forced off their land and lost their traditional way of life.

Advances in food production technology in the mid-19th century through the early half of the 20th century led to better diets, longer life expectancies, and increased population. These factors, combined with many displaced farmers due to the Enclosure Acts, led to a larger potential workforce for growing factories.

Mechanized agricultural technology created a shift in employment as fewer farmers and farm laborers were needed to produce more food. With fewer jobs in farming, workers looked to jobs created in the industrial or manufacturing sector of the economy. Since most of these industrial jobs existed in cities and new factory towns, rural-to-urban migration increased dramatically, which changed the cultural landscape and worldwide population distributions.

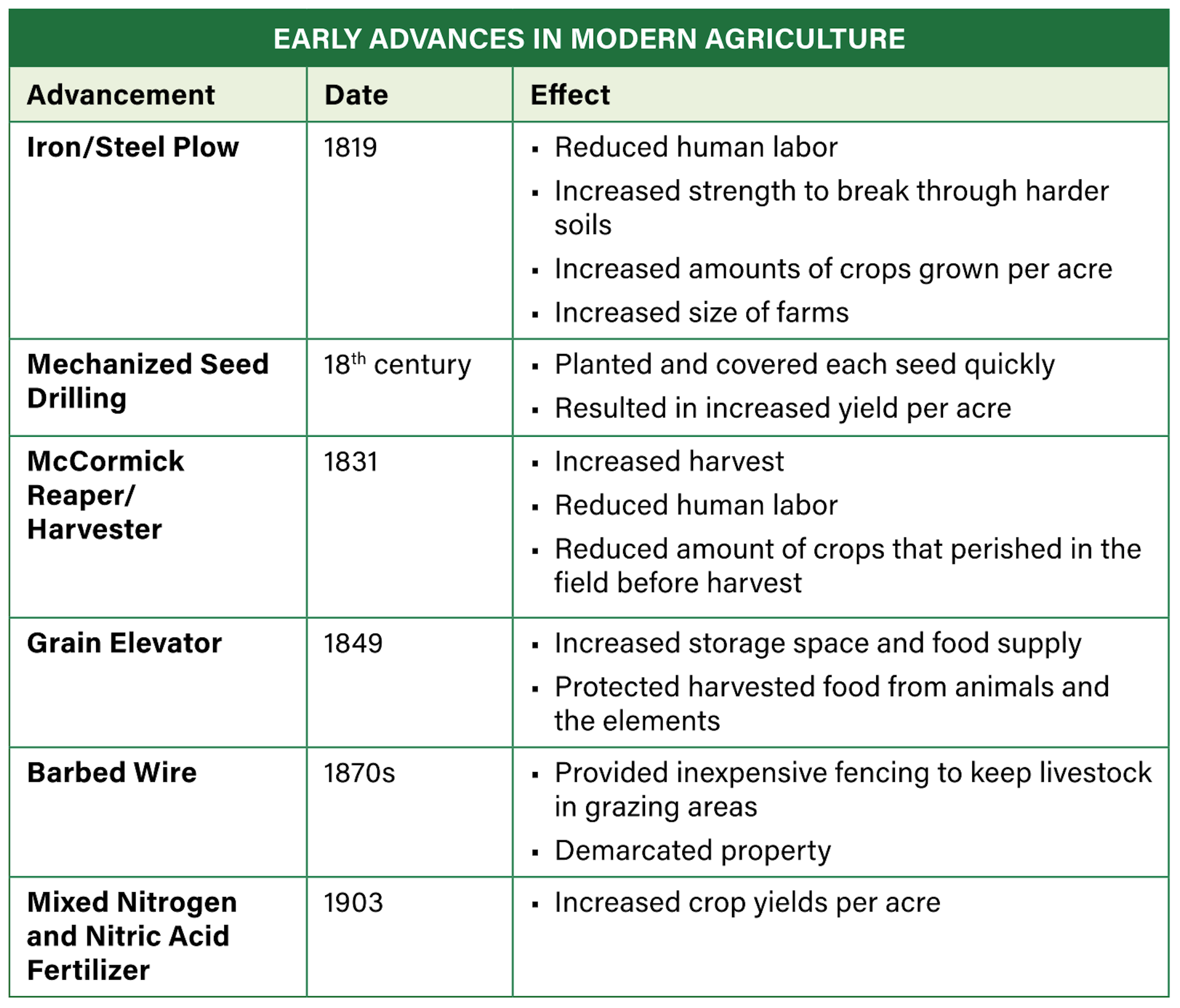

Agricultural advancements in sowing (planting) and reaping (harvesting), storage, irrigation, and transportation were made during the 19th century.

Farming techniques, like crop rotation and irrigation, increased yields and allowed farmers to produce a greater variety of food products. Crop rotation is the technique of planting different crops in a specific sequence on the same plot of land in order to restore nutrients back into the soil. Grains usually extract nitrogen from the soil, while alfalfa puts nitrogen into the soil. A fallow period (ground left unseeded) that allows the land to rest is also a common technique. Farmers significantly developed their understanding of proper soil management during the Second Agricultural Revolution.

Improved irrigation systems provided a stable and controlled water supply, thus increasing yields. Irrigation is the process of applying controlled amounts of water to crops using canals, pipes, sprinkler systems, or other human-made devices, rather than relying solely on rainfall.

During the same time period as the Second Agricultural Revolution, transportation infrastructure in Europe, the United States, and core regions improved dramatically with the greater use of roads, canals, ships, steamboats, and railroads. Additional improvements in the refrigeration of train cars and trucks further increased the distance goods could be transported while reducing the time that it took agricultural products to get to domestic urban markets. These transportation infrastructure improvements laid the foundation of a global trade explosion of the Third Agricultural Revolution.

Agricultural Changes and Shifting Demographics

The Second Agricultural Revolution resulted in fewer, yet larger and much more productive farms. This change caused a decrease in the number of farm owners and an even greater drop-off in the need for agricultural laborers. By the late 19th century, a large number of displaced farm laborers migrated to U.S. urban centers. The 1920 U.S. Census showed, for the first time in the country’s history, that more people lived in urban areas than in rural areas. Only 30 percent of the labor force worked in agriculture, less than half what it was in 1840. Today, only 3.6 percent of the U.S. workforce is involved with farming or related industries.

The Third Agricultural Revolution

In the mid-20th century, the Third Agricultural Revolution was born out of science, research, and technology, and it continues today. This revolution expanded mechanization of farming, developed new global agricultural systems, and used scientific and information technologies to further previous advances in agricultural production.

Researchers in core countries are responsible for most of the technological developments of the third revolution, but the benefits and impacts were global. This is most evident in vastly improved varieties of grain facilitated by crossbreeding seedlings in laboratories. These advances are at the heart of the Green Revolution, which is considered the most important aspect of the Third Agricultural Revolution.

The Green Revolution

The advances in plant biology of the mid-20th century are known as the Green Revolution. Dr. Norman Borlaug, considered the “Father of the Green Revolution,” laid the foundation for scientifically increasing the food supply to meet the demands of an ever-increasing global population. Borlaug’s development of higher-yield, more disease-resistant, and faster-growing varieties of grain are his most important contribution to the revolution. His work set in motion an entire movement that created hybrid wheat, rice, and corn seedlings. Borlaug’s research led to the modern method of plant breeding and eventually earned him a Nobel Peace Prize in 1970.

Borlaug worked specifically on developing a shorter grain of wheat that was both resistant to disease and capable of growing in harsher climates in Mexico. His work was successful in turning Mexico from a wheat-importing country to one that was self-sufficient and even had a wheat surplus. After his success in Mexico, Borlaug worked with governments in South Asia to deal with food shortages in the face of expanding populations.

Borlaug’s work and the resulting transfer of agricultural technology from the United States to Mexico and South Asia would serve as a model for the Green Revolution. Green Revolution scientists also encouraged farmers to double crop, or grow more than one crop in a year in the same field, while increasing the use of fertilizer and pesticides.

However, the benefits of increased food production were accompanied by concerns. The increased use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides led to fears about the unforeseen consequences of their use on farm products. Borlaug argued that the alternative of people dying from famine was not acceptable, and his research and methodology are credited with saving millions of lives.

Hybrid

Seed hybridization is the process of breeding two plants that have desirable characteristics to produce a single seed with both characteristics. For hundreds of years, humans created plant hybrids from local varieties available to them. However, Green Revolution scientists focused their attention on grains. Further, living in an increasingly globalized world, these scientists had a much wider range of plants from which to crossbreed than did local farmers. Scientists used hybridization to create a new strain of rice in the 1960s. They used long-grain rice from Indonesia and dense-grain dwarf rice of Taiwan to produce a rice grain that was both longer and denser. The hybrid of these two strains was introduced to rice-growing countries in East and Southeast Asia.

Machinery

In addition to using hybrids, chemical fertilizers, and pesticides, proponents of the Green Revolution encouraged the transfer of mechanical technology as well. Machinery such as tractors, tillers, broadcast seeders, and grain carts were introduced to countries of the developing world. The introduction of these agricultural technologies assisted in production and challenged traditional labor-intensive farming practices that had been in place for thousands of years.

GMOs

Hybridization differs from the production of a genetically modified organism (GMO), a process by which humans use engineering techniques to change the DNA of a seed. They have been developed to increase yields, resist diseases, and withstand the chemicals used to kill weeds and pests.

Positive Impacts of the Green Revolution

During the Green Revolution, global food production increased dramatically. The introduction of new seed technology, mechanization, pesticides, chemical (human-made) fertilizers, and irrigation led to increased yields. More food led to reduced hunger, lower death rates, and growing populations in many parts of the developing world.

Higher Yields

Increased food production in the developing world has prevented millions from starvation. By the mid-1950s, crop yields had increased without cultivating more land. The increased yields have kept up with global population growth, but experts debate whether agricultural production increases or population increases will be greater in the future.

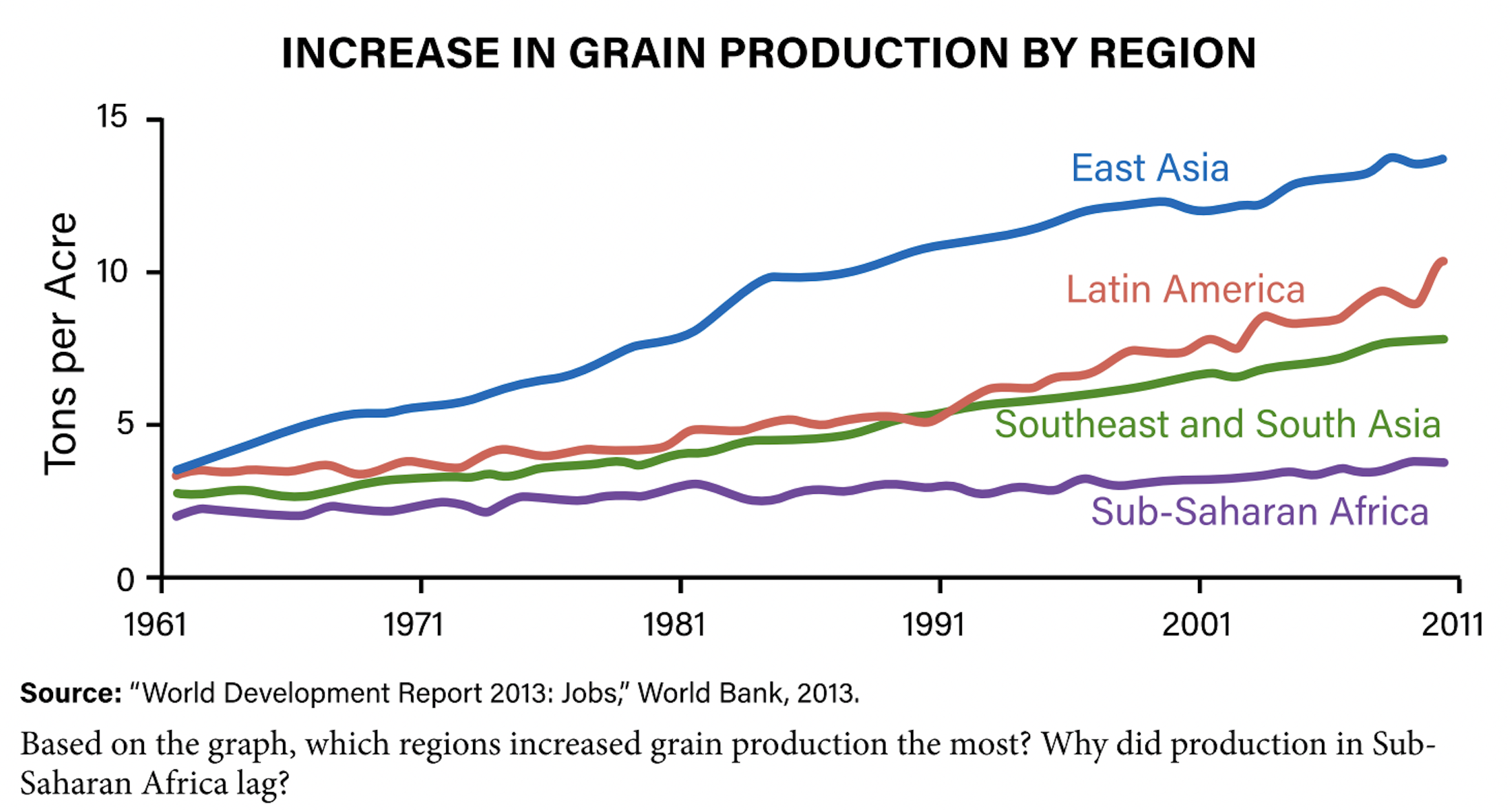

Similar to what occurred in Mexico, India went from being an importer of wheat to harvesting a surplus of wheat within a few decades after World War II. India’s increased wheat output helped curb hunger in South Asia. The Green Revolution was also successful in Latin America, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. The worldwide result of the Green Revolution was higher yields on the same amount of land. Despite rapid population growth in many regions during the mid- to late 20th century, the increased crop output helped to stave off hunger and famine. By the second decade of the 21st century, the World Bank estimated that 80 percent of the developing world’s population had an adequate diet. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome, Italy, reported the following yield increases from 1960 to 2000:

- wheat: 208%

- corn: 157%

- rice: 109%

- potatoes: 78%

Money for Research and Business

The Green Revolution helped to create high rates of investment in both the public and private sectors. Research for seed hybridization, fertilizer, and pesticides was funded by governments and universities in developed countries, led by the United States. This research was then used by for-profit corporations to create and market the products farmers used. While the Green Revolution benefited people in poor regions, it also financially benefited universities and corporations in more prosperous regions.

Food Prices

Higher yields and increased production led to falling real food prices, or prices adjusted for inflation. The supply of certain crops, mainly wheat, corn, and rice, grew through the mid- to late 20th century and led to lower prices. More food at affordable prices helped to ease the economic stress of hunger and famine on governments and economic systems in the developing world. However, starting in 2005, global food prices began to rise which triggered large-scale protests in many countries and increased concerns about food insecurity.

Negative Consequences of the Green Revolution

Like all large and rapid changes, the Green Revolution had some negative consequences. Some of these were environmental damages, gender inequalities, economic obstacles, and failures in Africa.

Much of the success of the Green Revolution hinged on human-manufactured products such as hybrid seeds, chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and fossil-fuel using equipment. While crop yields increased, they often did so at the expense of the natural environment. The intensive use of land and double or triple cropping, combined with more aggressive irrigation, led to soil erosion and increased environmental pollution. Critics of the Green Revolution argued that it was not a sustainable system.

Farming practices during the Green Revolution increasingly drained the soil of its natural nutrients, which led to more use of and dependency on human-made fertilizers. The introduction of these chemicals to the environment resulted in potentially hazardous runoff into streams, rivers, and lakes, which posed serious consequences to the local ecosystems, habitats, and communities. Hazards included polluted drinking water, species extinction, and health issues for the population.

The transfer of technology from developed countries to developing countries included machinery such as tractors, tillers, and harvesters. These new technologies required vast amounts of fossil fuels, which increased air, water, and sound pollution. In order for the Green Revolution to succeed, it needed mechanization to keep up with crop production, thus resulting in further environmental stress.

The Green Revolution’s Impact on Gender Roles

Many countries in the developing world that participated in the Green Revolution had traditional economies. In a traditional economy, subsistence farming is the cornerstone of economic activity. Even though much of the farming labor is performed by women, men usually dominate socially, politically, and economically based on many societies’ traditional beliefs. When the Green Revolution and its technologies were introduced to these countries, it was often men who benefited and were given decision-making powers. Men owned the land, had access to financial resources, and were educated on newer methods of farming, while women were often excluded from these opportunities. This further marginalized women and limited their role within many societies.

Economic Changes

The initial successes of the Green Revolution were a mixture of private and public investments. The transfer of farming technology heavily relied on private investment by corporations and public support by governments. As the amount of research and production increased, so too did the cost. Machinery, seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides became more expensive and the cost was passed on to farmers in the developing world and the organizations that supported them. As profit margins decreased, many corporations began to curtail further investments in the Green Revolution. Without a clear financial incentive, the motivation to invest waned.

In addition, the labor markets of less-developed countries changed. As with the Second Agricultural Revolution, the Green Revolution allowed, or pushed, people from rural areas to move to urban areas in search of industrial and service sector jobs. Demographers predict that migration from rural to urban areas in the developing world will continue. In the future, the percentage of people living in cities will continue to increase.

People in the developing world had unequal access to Green Revolution technology. Income, accessibility, and government policies played a role in which people and regions of a country had access to or could afford the technologies. The wealthy and transportation-connected core areas have advantages over the outlying, isolated, and poor periphery areas of a country, resulting in uneven development.

The Green Revolution’s Struggles in Africa

Unlike Latin America and Asia, Africa benefited very little from the successes of the Green Revolution. The reasons the Green Revolution failed throughout the continent of Africa are environmental, economic, and cultural.

Africa has a greater diversity of climate and soils than other places. Hence, the development of the right fertilizers proved to be very expensive. Africa has many regions with harsh environmental conditions. Insects, plants, and viral strains proved to be extremely challenging to the Green Revolution researchers and their technology. Africa is large and lacks a well-developed transportation infrastructure, so the costs of investment in research, development, and transportation were very high.

Africa’s staple crops such as sorghum, millet, cassava, yams, cowpeas, and peanuts were not always included in research for seed-hybridization programs.

During the Green Revolution, the world’s population more than doubled. Most of this growth was in poor countries on the periphery of the global economy. From the mid-20th into the 21st centuries, Africa had the highest population growth rate of any continent. Since that is where the Green Revolution had the least impact, hunger remains a greater problem there than elsewhere. Today, nearly 30 percent of Africa’s population has been affected by food insecurity.

In response to the ongoing food problems in Africa, private foundations and governments are working together. They hope to develop a new Green Revolution there, using updated technology.