Spatial Concepts-Distance

distance decay

time-space compression

flow

Scale

global scale

national scale

regional scale

local scale

Spatial Concepts-location

site

situation

absolute location

relative location

place

sense of place

placelessness

Target Stores & Distance Decay

So much of what you’ll learn this year will be concepts that you interact with in your everyday life, but never realized there was a name for it or analyzed it much. Human geography is everywhere.

I moved to Santa Cruz County in 2009 to attend graduate school at UCSC. The first place I lived was in Felton, which turned out to be a big mistake, but I corrected it a few months later. I rented a bedroom in Aptos, and then, as soon as I received my first paycheck, I found a small apartment in Santa Cruz. I needed plates, silverware, pots and pans, and cooking utensils. I needed bathroom and shower mats, some small pieces of furniture, and all the other small things you need for an apartment. The only Target at that time was in Watsonville, and I would drive to Watsonville on the weekend to shop at Target. I did make one or two trips over the hill to Ikea where I purchased a dresser, a couch, and a bag or two of smaller items, but driving over the hill and dealing with all the freeway traffic isn’t something you do if you just needed a can opener. The same was true for Target since it was a bit of a drive as well.

It is someone’s job at Target to find places where people like me, and others like me exist. They use concepts like distance decay and relative distance to determine if their store placement is maximizing customer spending, and determine if it’s worth spending the money for the corporation to build an additional store and all the costs that go along with that.

In this case, they knew that potential customers living in the central to the northern half of Santa Cruz County probably wouldn’t make a trip to their stores in the hours after people get off work, which is usually the busiest time for grocery stores and stores like Target. That is because the relative distance between Santa Cruz and Watsonville could be well over 1 hour with gridlock traffic. Who the hell wants to sit in traffic for over an hour to buy a can opener? But how many people might buy the can opener if the trip was shorter and easier? By tracking customer zip codes, Target could analyze the flow patterns of where their customers were coming from and what times those customers shopped.

They saw that the distance decay was nearly absolute during the weekday peak shopping times, meaning that shoppers perceived it as too far away because of its relative distance. We now have a Target store in Capitola.

On the other hand, Ikea knows shoppers are willing to travel a longer distance. The range and threshold of an Ikea store, meaning how far customers will travel and how many customer sales are needed to keep a place in business, are different from Target’s. Its range radius is larger, and so is its threshold. There aren’t enough customers in Santa Cruz to keep an Ikea open.

The Time-Space Compression

Technology has the effect of overcoming distance decay. Before the telephone, the common way of communicating across distance was through letter writing. That took some time, weeks or even months, over horseback or sea travel.

A telephone conversation is a heck of a lot quicker than writing letters back and forth. So, it compressed the time it took for communication to travel through space.

As a result of the time-space compression, the flow of ideas, people, and goods increases. It is easier to communicate with someone in New York or travel to Europe than 100 years ago. The result? More people are traveling to Europe, and more people are communicating with people in New York. The increasing flow (of communication, exchange of goods, ideas, and people) leads to new innovations that lead to more exchange of goods and services, and the cycle becomes cyclical. That is the definitional importance of this concept, but I want you to understand its world-changing implications because that’s much more interesting. Understanding this helps us understand why we are living during a period of rapid change.

Let’s look at cell phones as an example. The time-space compression makes what was once impossible possible. I love to imagine what it would be like for someone alive in the year 1500 to come back to life and see this world. In their lifetime, the only products anyone had depended on the resources nearby, and the brainpower and skill of individuals to assemble and build. Trade happened one sailboat at a time, and the idea of communicating with and depending on multiple partners and factories around the globe would be impossible. Which is why change happened so slowly for such a long time.

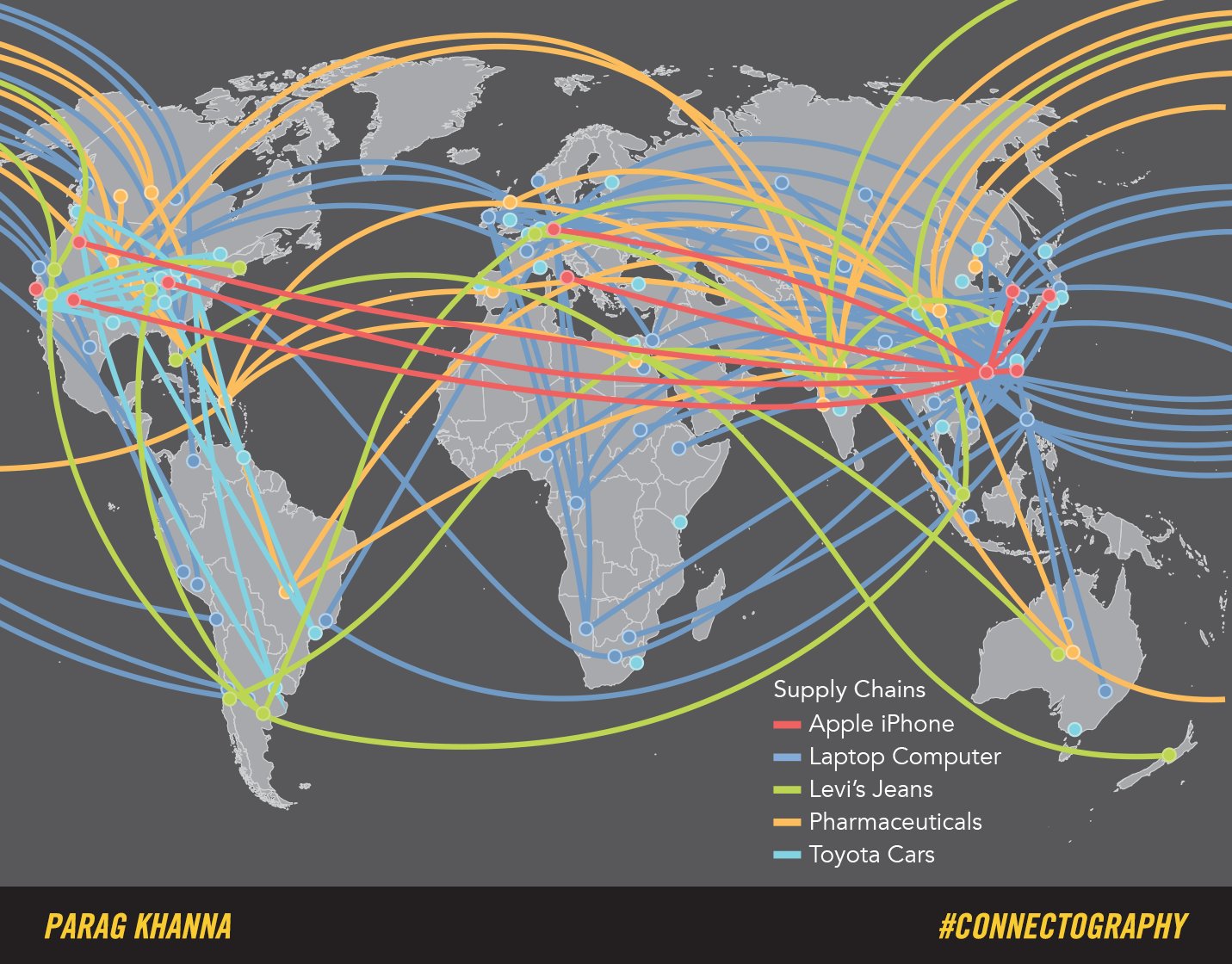

Because of efficient travel, shipping, and communication, we have created a complex global supply chain. We no longer rely on local resources and brainpower; today, we have access on a global scale.

The map above displays supply chains for items most of us depend on. Today, it is more efficient to ship raw resources and individual components around the globe, eventually coming together in an assembly factory, than to build products from scratch in one factory. The laptop I’m using right now portably started in Africa, where minerals and raw resources were collected and shipped to Brazil for battery assembly, India for screen and plastic components, to South Korea for microchips, to Japan for assembly, and then to China for processing and shipping before finally arriving on a giant cargo ship on its way to an Apple Store.

It’s difficult to fully grasp all of the education, research, innovation, and exchange of ideas needed to make something like this possible. I mean, think about the generations of people who would become educated, educate others, and collaborate to take an existing technology and use it to create something entirely new. Each breakthrough opens the doors for a new breakthrough. With each cycle, the pace of change and innovation increases, which is why such rapid and dramatic changes mark our lives today. We are the first humans to walk this Earth and experience this level of rapid change, and recent breakthroughs in AI tech show us that this rate of change is about to increase dramatically.

This is both exciting and a bit scary. These innovations destroy jobs and industries but also create new jobs and new industries. Unfortunately (as we’ll learn in subsequent units), the individuals harmed by the disappearing jobs are usually not the same individuals who benefit from new industries.

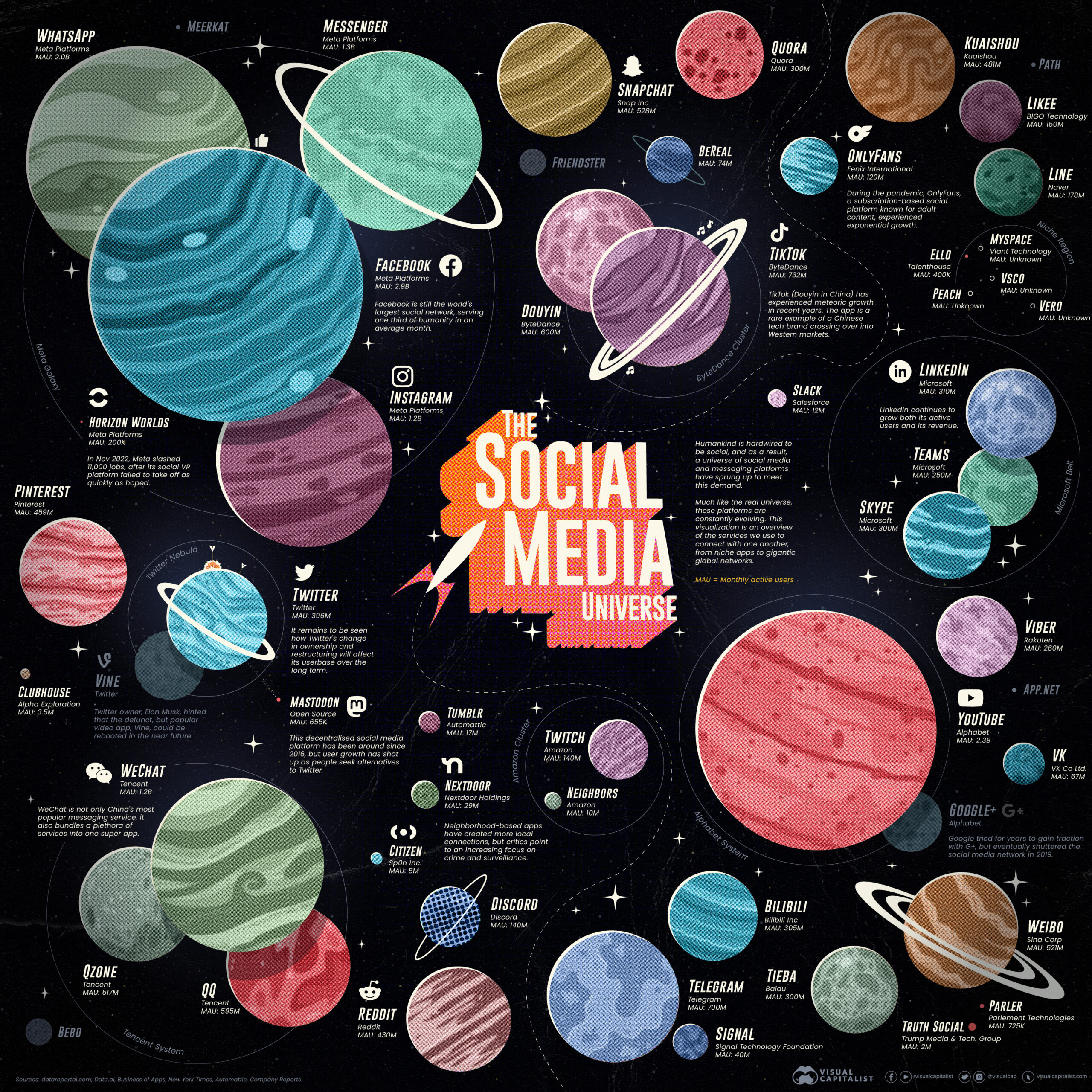

Social media is a good example. It began as a silly thing that college kids used, and because of the system described above, it unfolded into what we see today. Meta, the company that owns Instagram, employs about 70,000 people. But that’s only the people who work directly for the company. Just about every major company has a team of social media marketers who engage with independent influencers to market products. Giant data centers house the servers, creating manufacturing and operations jobs. Then consider all of the people who use social media as part of their work: photographers, music producers, real estate agents, and even teachers!

In 2023 the social media industry was estimated to be worth $90 billion.

Analyzing Spatial Patterns

As I hope you can see now, the human geography lens for understanding the world is very interested in analyzing how different places are connected, the uniqueness of places, how people and places interact and influence one another, and the flow of people, ideas, and goods.

Spatial Distribution

The reason this type of analysis is so important is that it’s a powerful tool that’s easy to use in so many different circumstances. We can think of this tool almost like a math formula:

Spatial Distribution = Density (amount) + Concentration (how it’s spread) + Pattern (its arrangement)

A spatial distribution analysis provides powerful insight into a space’s purpose and use and its reflections about people and what they value. It’s a tool we’ll use in every unit.

Space & Place

Spatial analysis involves examining a place, which is made up of human and physical factors. A place can create a sense of place, which is a unique feeling only associated with a place. Or a lack of a sense of place, which is called placelessness. Let’s use the image collage below for an example.

We can see human factors like language, religion, and the style and architecture of buildings. I’m leaving some out so you can take a closer look and practice. Physical factors like the mountains in the background, the flat topography, the river (and more).

The unique architecture of our historic buildings on Main Street, the plaza and gazebo, and town landmarks like Fox Theatre create a sense of place. The use of space to hold an annual Strawberry Festival is called placemaking, which is how we make a space a place.

We also consider site factors, such as the Pajaro River, the mild climate of an oceanside town, and the valley’s flatness, which is conducive to agricultural production.

Situational factors include our proximity to economic centers (or hubs) like Silicon Valley and transportation networks that place Watsonville between the tourist industry in Santa Cruz and Monterey.

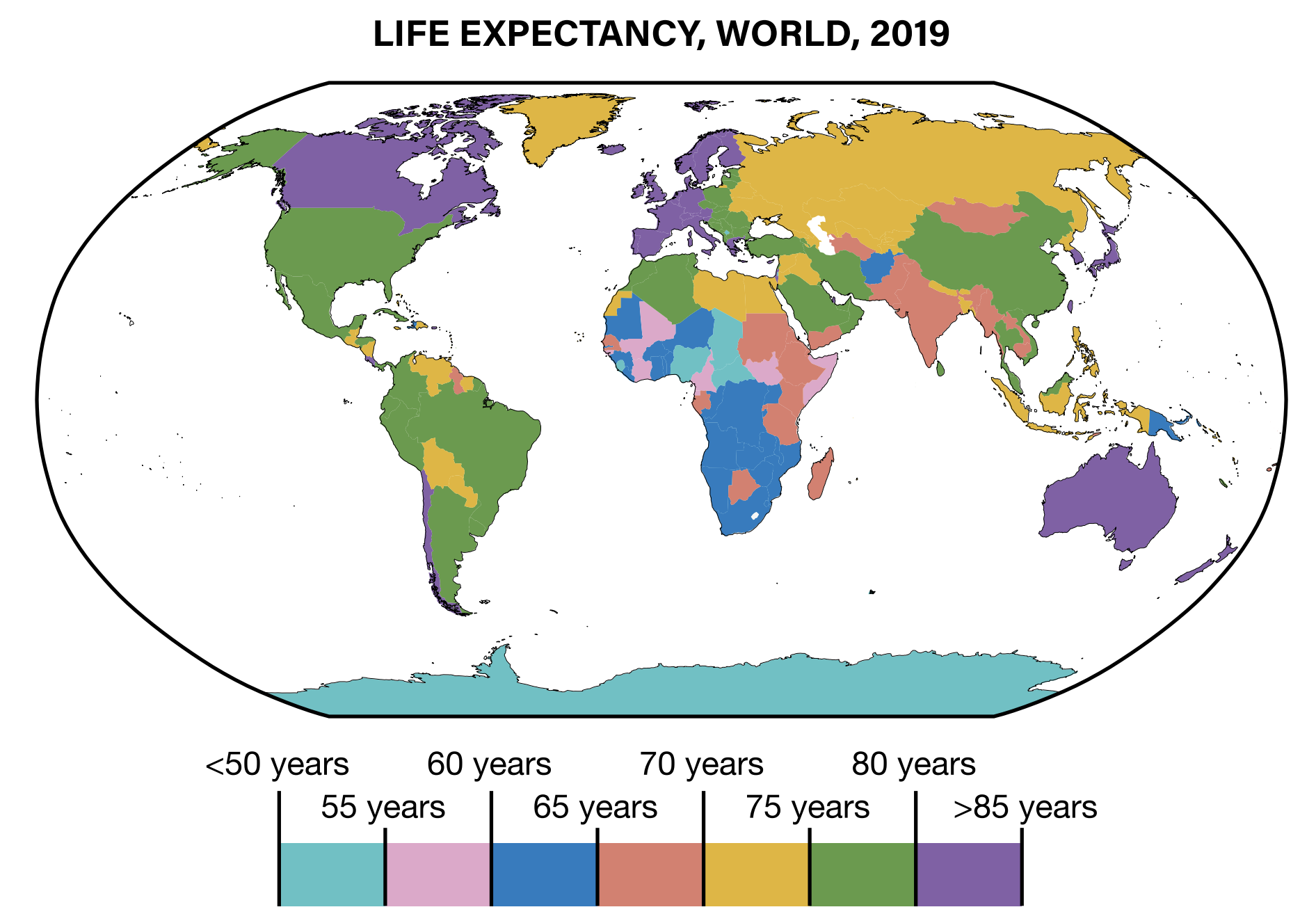

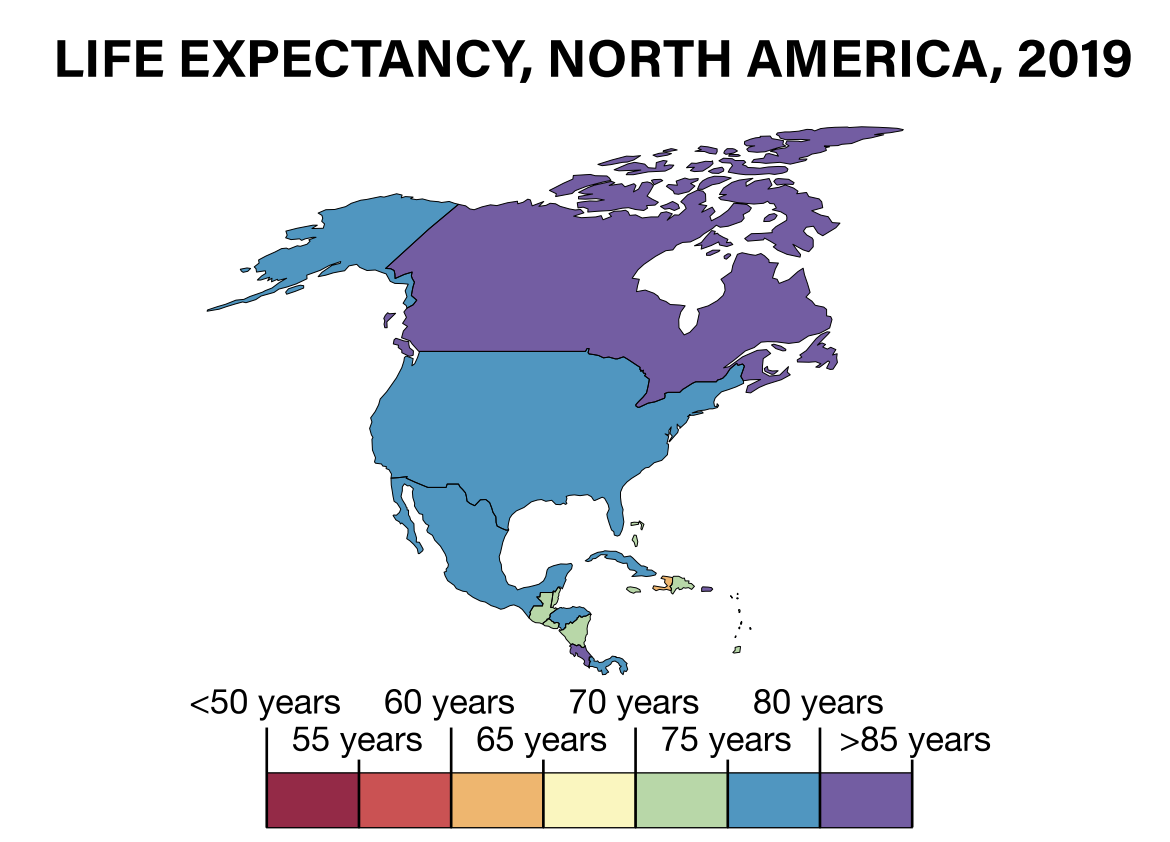

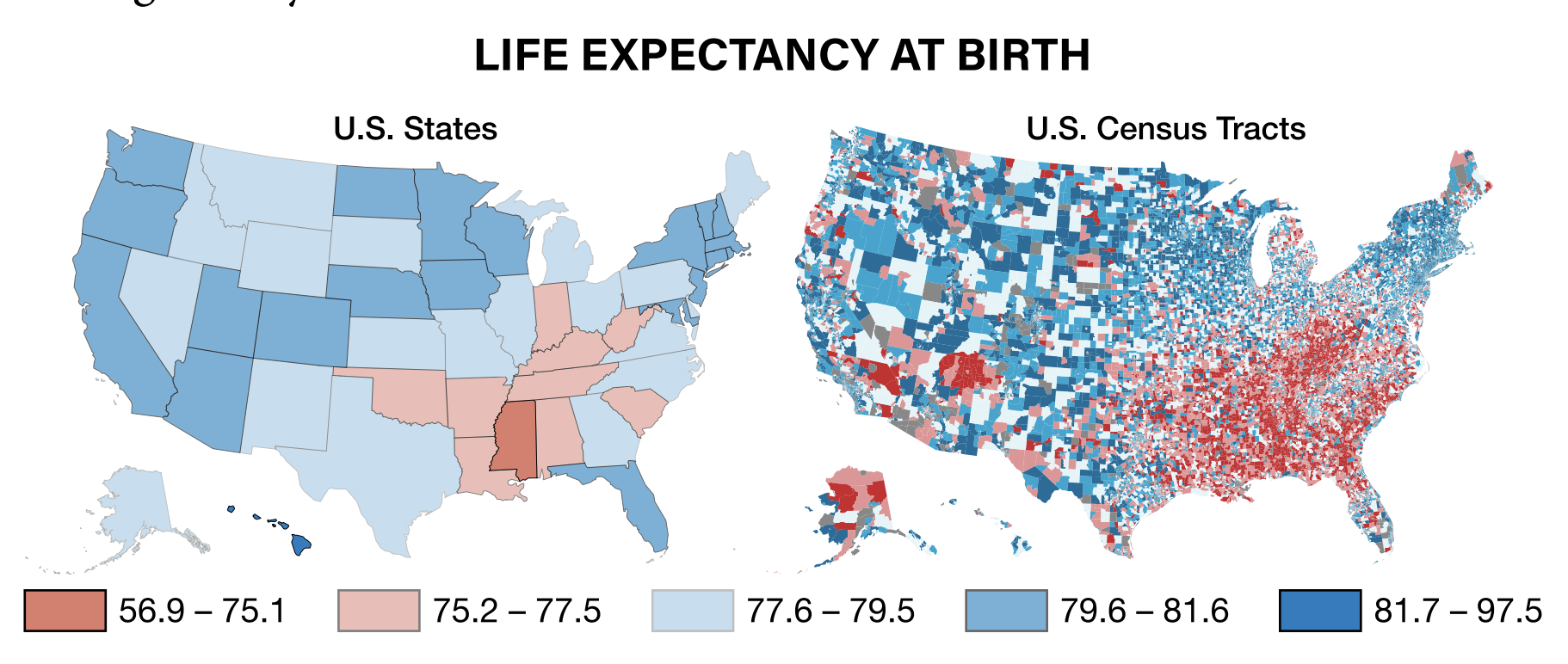

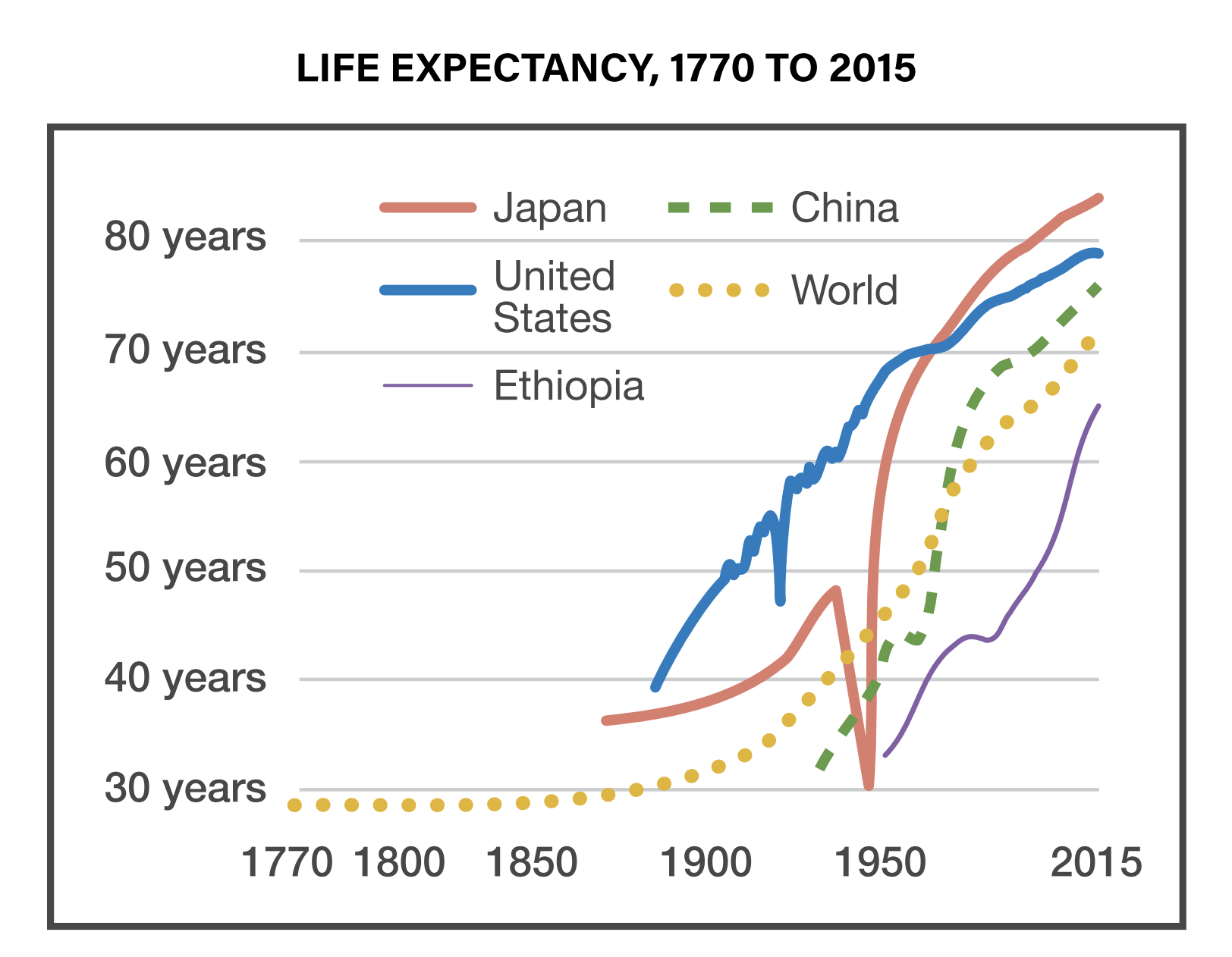

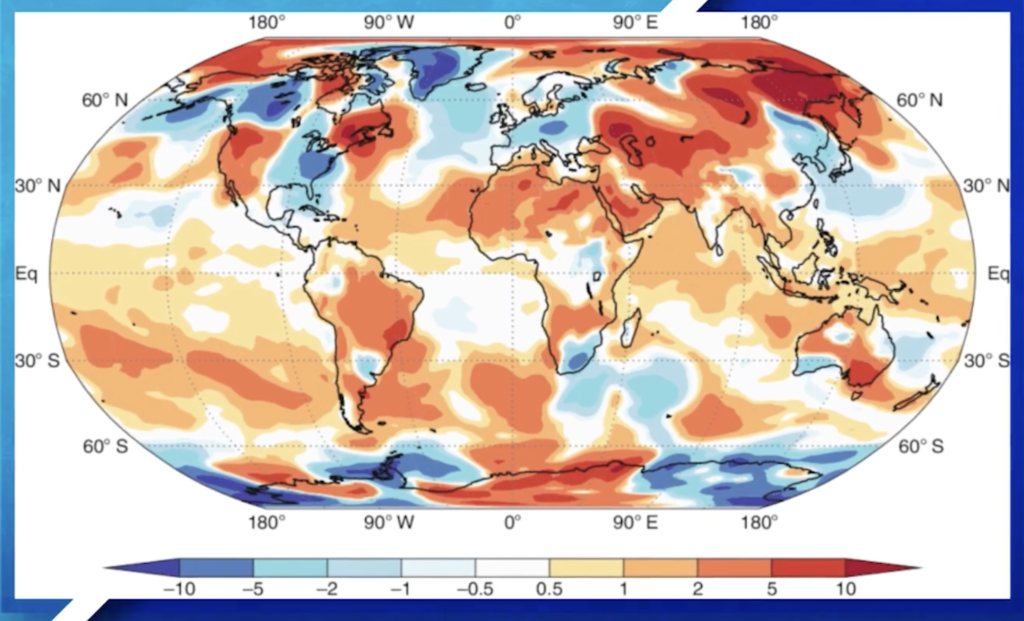

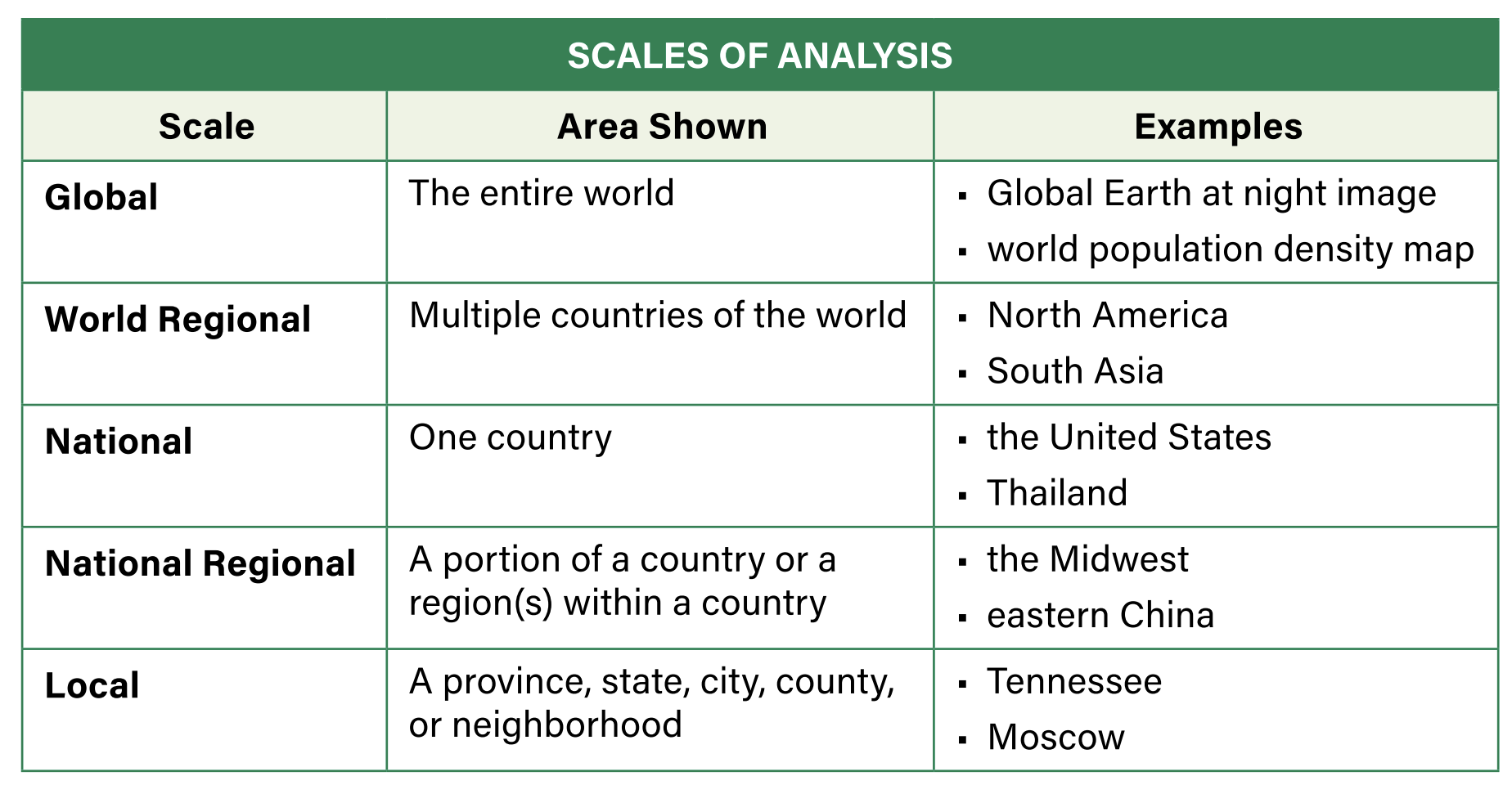

Scale of Analysis

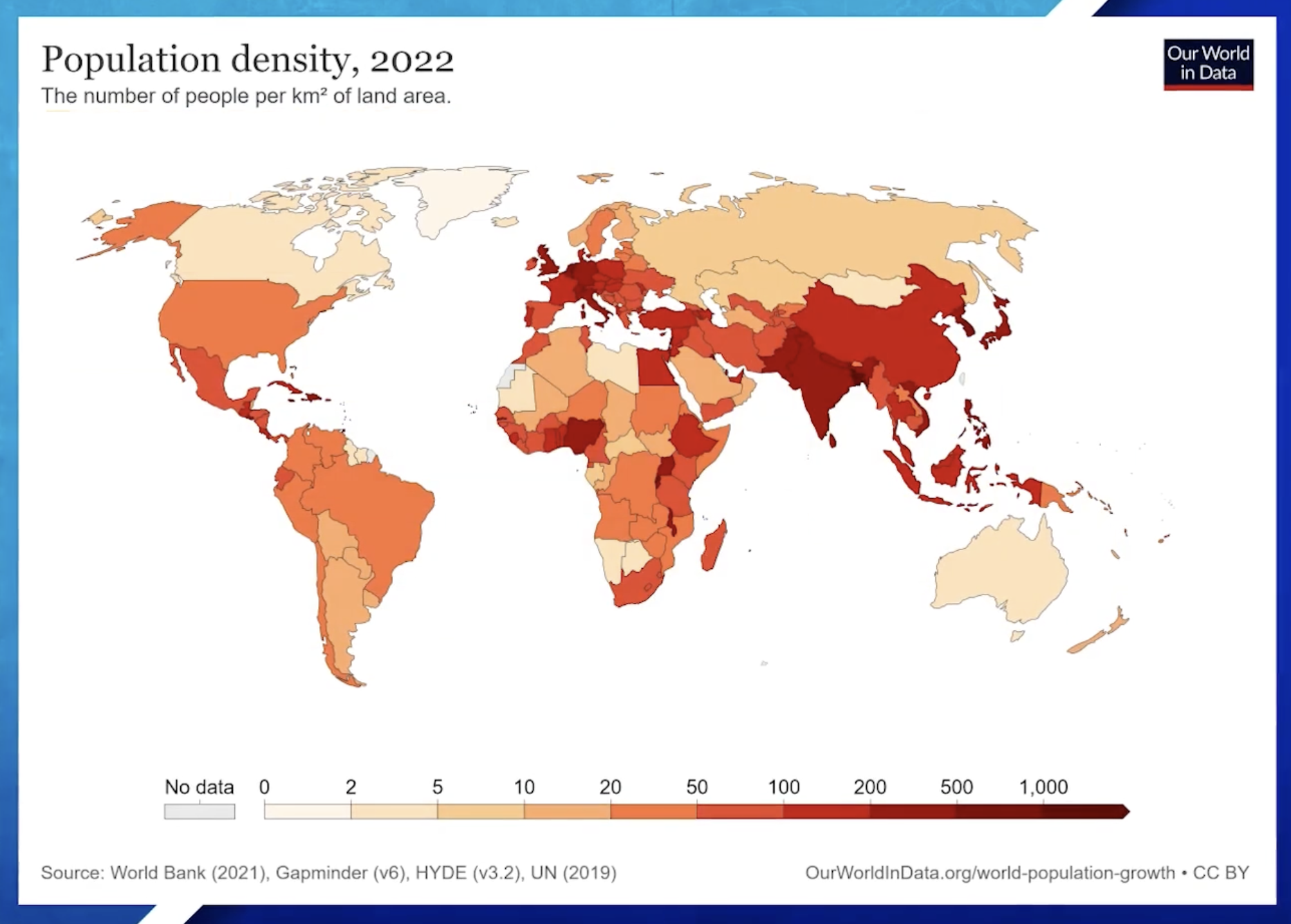

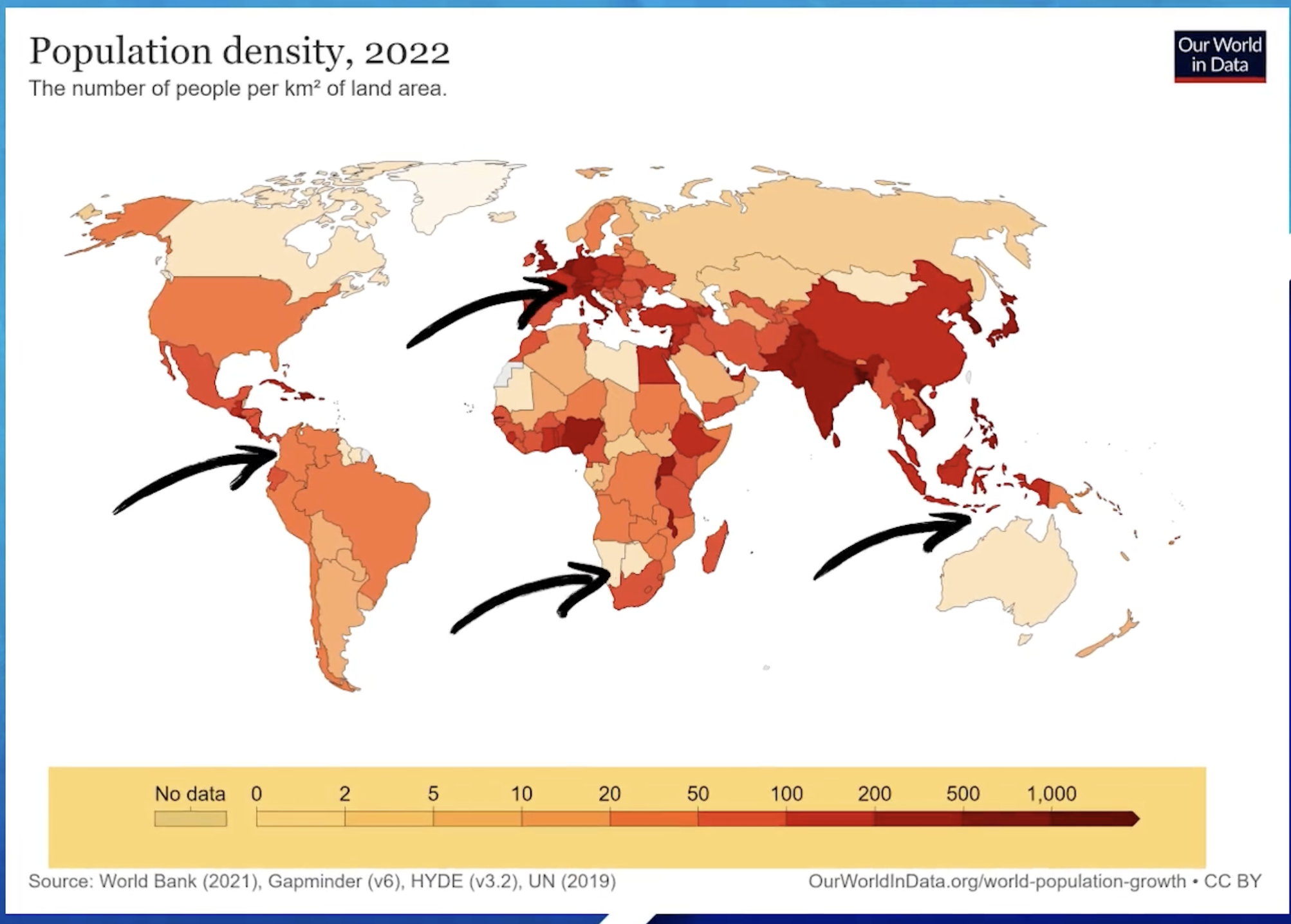

Finally, the last part of this spatial analysis approach includes scale of analysis, which really just refers to different levels of data. For example, we could look at the average household wages for everyone in the United States. That could be useful, but we can learn even more if we change that scale of analysis to see average wages by state, county, city, or even neighborhood.

It’s not that one scale of analysis is better than the other. The important point here is that we can deepen our understanding each time we change our scale of analysis. It’s one of those tools in our human geography toolbox that will help us build the new worldview we’re building this year.

Some more examples below to practice