Social & Political Challenges

Racial & Economic Injustice

de-facto segregation

redlining

blockbusting

white flight

Social/Cultural Sustainability

re-vitalization and urban renewal

re-zoning for mixed use

inclusionary zones

brownfield redevelopment

gentrification

Sustainability Challenges

urban sprawl

growth boundary

infill development

Economic Challenges

urban blight

de-industrialization

disamenity zones

informal settlements

Cities around the world are centers of innovation, culture, and economic opportunity, but they also face significant challenges that shape the daily lives of billions of people. As cities grow rapidly, they struggle to balance environmental sustainability with increasing pressures on infrastructure and natural resources. Issues such as air and water pollution, waste management, and maintaining green spaces become urgent priorities as populations expand.

Economic disparities and racial injustices are deeply embedded in many urban areas. Patterns of inequality often result in stark differences in access to quality education, healthcare, employment opportunities, and safe living conditions. Historical and systemic racism has shaped neighborhoods in ways that persist today, leading to segregation, poverty, and cycles of disadvantage that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

Another key challenge in cities is maintaining the affordability and sustainability of neighborhoods. Rising housing costs often push long-time residents out of their communities, triggering processes like gentrification. While gentrification can bring economic growth, it frequently comes at the cost of cultural displacement, loss of community identity, and increased homelessness. The lack of affordable housing solutions intensifies these pressures, creating barriers to stable living environments for many urban dwellers.

Urban sprawl, characterized by uncontrolled outward expansion of cities, creates additional complications. It stretches infrastructure, intensifies reliance on automobiles, and undermines efforts toward sustainable city planning. Sprawl can result in fragmented communities, increased pollution, and inefficient use of land and resources.

Finally, many global cities contain informal settlements and disamenity zones—areas marked by inadequate infrastructure, poor sanitation, limited economic opportunities, and minimal governmental support. Residents of these neighborhoods frequently face severe social and economic exclusion. Understanding the economic, political, and social forces behind these challenges is essential to developing thoughtful policies and sustainable solutions that make cities equitable and livable for all residents.

Social and Political Challenges

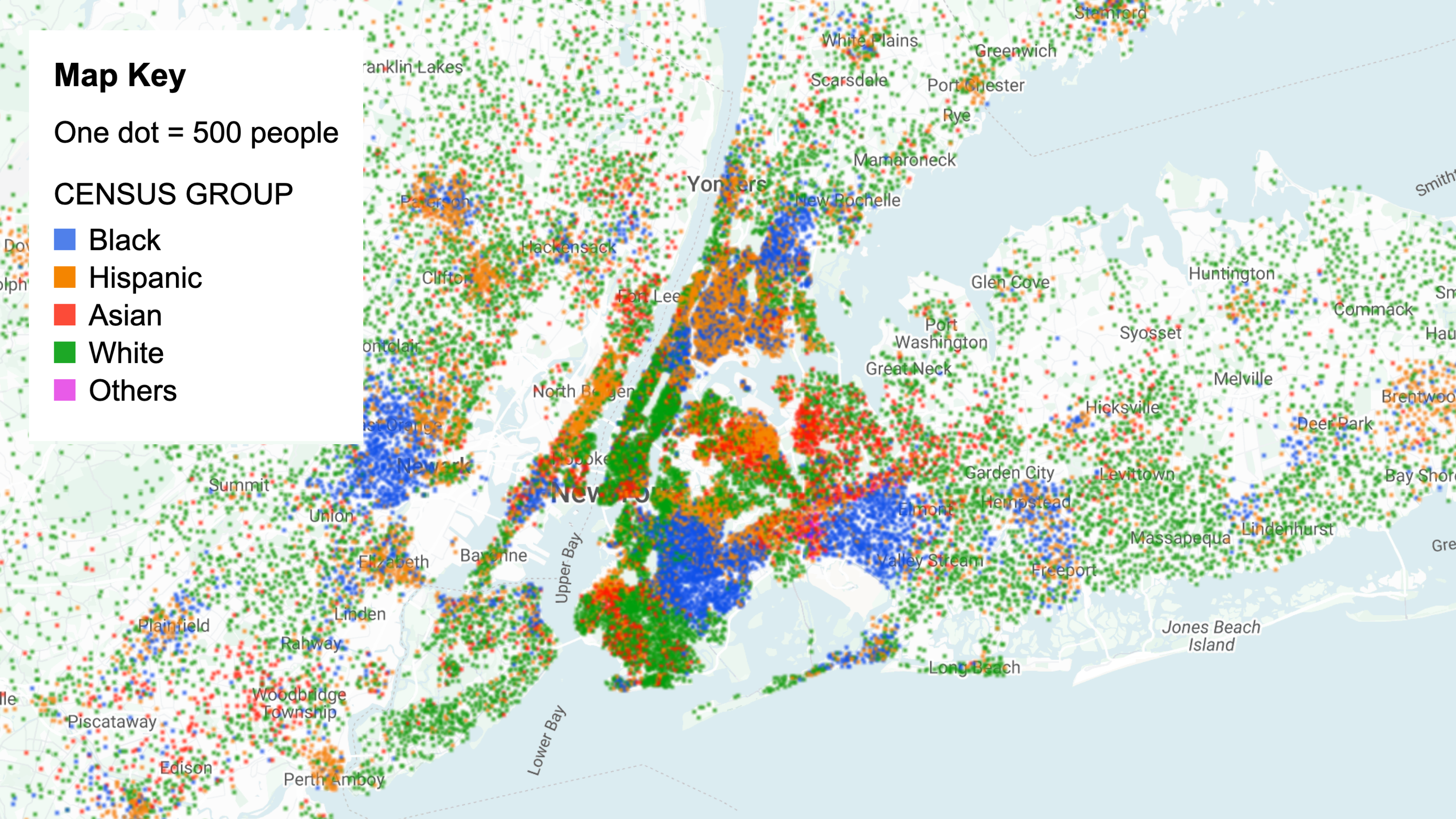

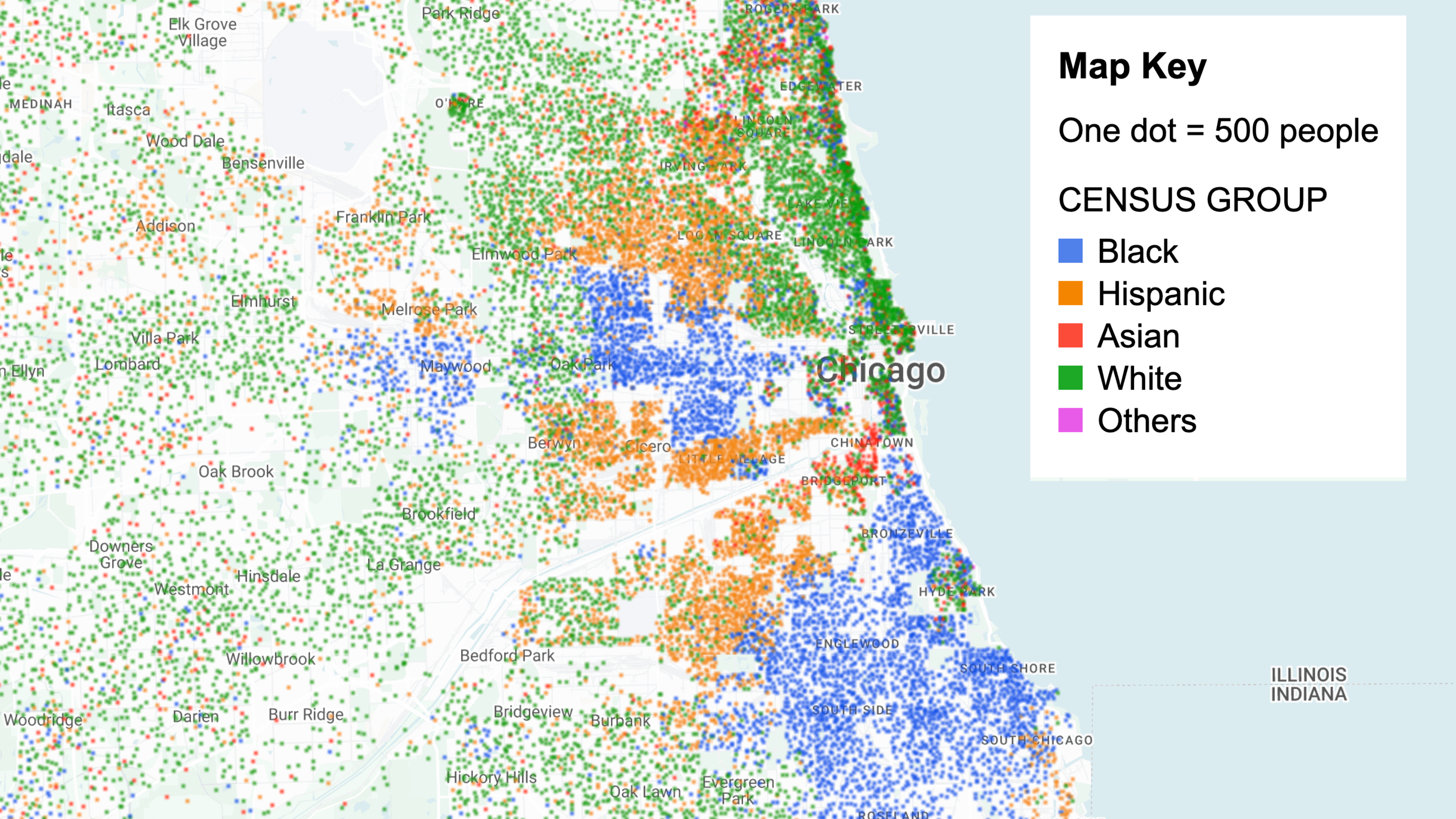

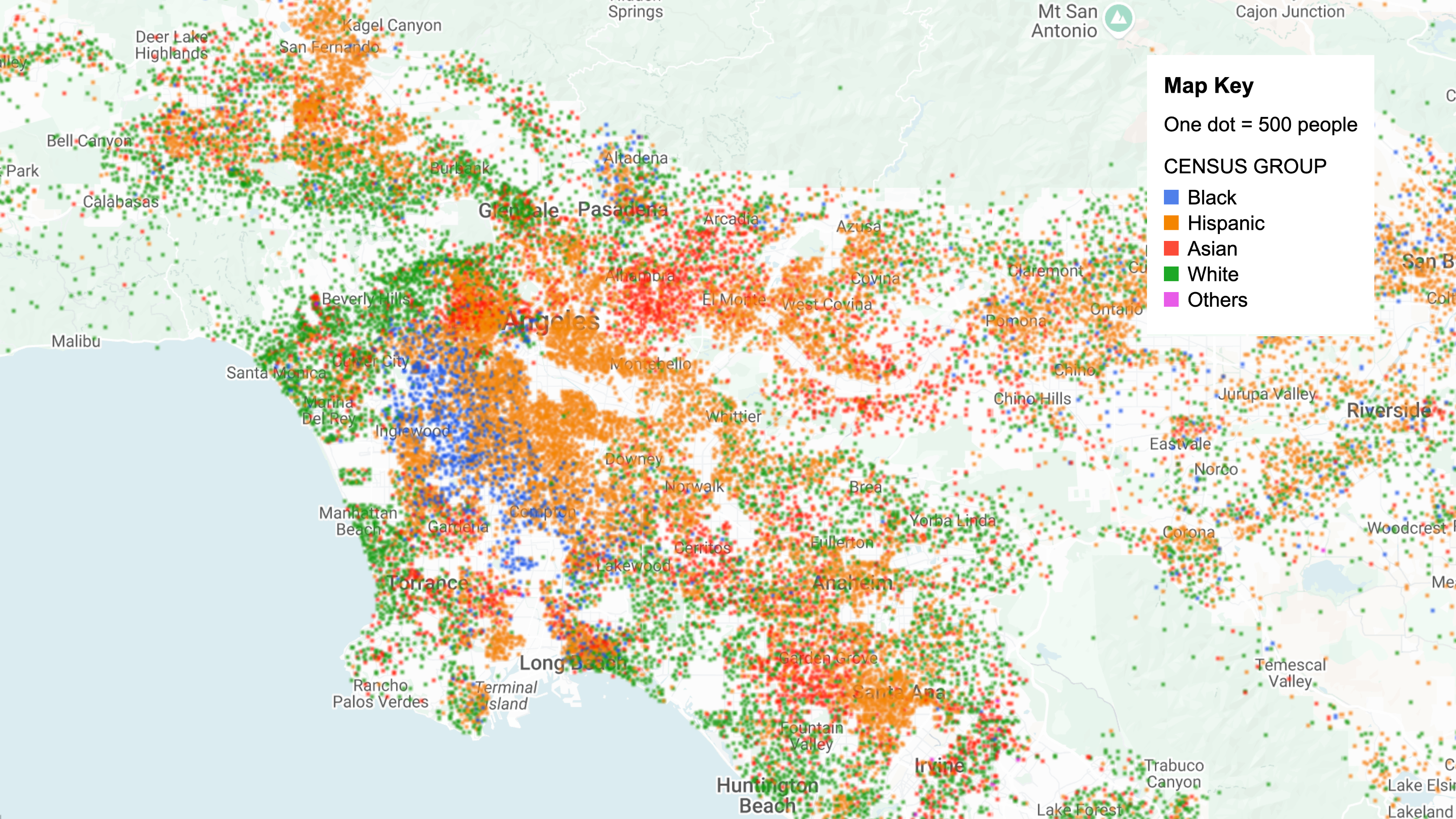

Cities today remain visibly shaped by histories of racial and economic segregation. Major urban centers like Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York provide clear examples where divisions along racial and economic lines persist, often tracing back to discriminatory policies and practices enacted decades ago. Neighborhoods separated by race and wealth reflect a legacy rooted in deliberate social engineering, whose consequences remain deeply embedded in contemporary urban landscapes.

Redlining

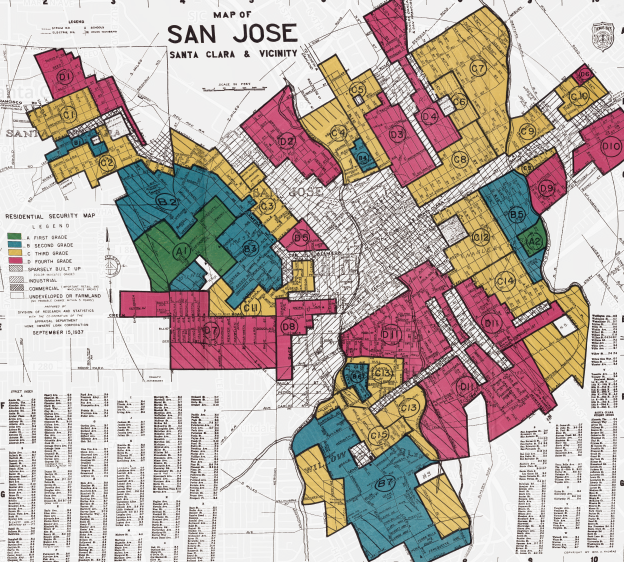

Historically, redlining was a government-sanctioned practice beginning in the 1930s, in which neighborhoods were systematically rated according to perceived financial risk, largely based on racial composition. Neighborhoods with high minority populations were marked in red on government maps, indicating areas considered “hazardous” for investment. Banks and insurance companies subsequently denied loans, mortgages, and other financial services to residents within these redlined communities, disproportionately affecting Black families and other minorities.

Blockbusting

Alongside redlining, real estate practices such as blockbusting further deepened racial divides. Blockbusting occurred when real estate agents intentionally stoked fear among white homeowners by suggesting that racial minorities moving into their neighborhoods would lead to declining property values. White families, driven by this fear, quickly sold their homes at reduced prices, after which these homes were resold to minority buyers at inflated costs. This exploitation accelerated racial turnover in neighborhoods, reinforcing segregation and extracting wealth from minority communities.

These dynamics drove the phenomenon known as white flight—the migration of white families from urban centers to suburban areas. As white residents departed, so did essential resources, investment, and political attention, leaving behind economically disadvantaged neighborhoods. This exodus compounded existing inequalities and concentrated poverty in inner-city communities, limiting opportunities for residents left behind.

The long-term effects of redlining, blockbusting, and white flight remain starkly visible today. Families denied the ability to purchase homes in thriving neighborhoods lost a primary means of accumulating generational wealth. Over generations, this wealth gap widened, resulting in fewer economic opportunities, less access to quality education, and reduced financial security for affected communities. The impact of these practices continues to shape the economic realities faced by many individuals and neighborhoods across America’s urban landscape.

Effects of Deindustrialization

Deindustrialization refers to the widespread loss or decline of industrial activity, especially in manufacturing, within a city or region. This process began in many developed countries, including the United States, during the late 20th century, driven by globalization, technological advancements, and shifts toward service-oriented economies. As factories closed or relocated to countries with lower labor costs, cities once thriving with industry faced severe economic and social disruption.

The effects of deindustrialization can be profound. Economically, the loss of manufacturing jobs often leads to high unemployment rates, reduced incomes, and weakened local economies. Once-vibrant industrial neighborhoods may become economically stagnant, characterized by abandoned factories, vacant buildings, and deteriorating infrastructure. This economic decline frequently leads to a reduced tax base, limiting local governments’ abilities to invest in critical services such as education, public safety, and infrastructure maintenance.

Socially, deindustrialization contributes to higher levels of poverty, population loss, and social instability. As employment opportunities diminish, residents who can afford to leave often do, intensifying a city’s demographic decline and leaving behind marginalized populations with fewer opportunities. This contributes to rising inequality, increased crime rates, deteriorating public health, and diminished overall quality of life.

Today, many cities that experienced deindustrialization—often referred to as “Rust Belt” cities in the United States—continue to face these long-lasting economic and social consequences. Efforts to revitalize these cities through redevelopment, investments in new economic sectors, and improved social services highlight the ongoing struggle to overcome the impacts of industrial decline.

Creation of Disamenity Zones

Deindustrialization often leads to the formation of disamenity zones—areas within cities characterized by inadequate infrastructure, limited public services, and poor living conditions. As industries close and residents lose stable employment, neighborhoods suffer from reduced economic activity and diminished investment. Businesses such as grocery stores, healthcare providers, banks, and public services become scarce or disappear entirely, leaving residents with significantly reduced access to essential goods and services.

Without convenient access to healthy food, healthcare, quality education, and transportation, the residents of disamenity zones face additional barriers to economic stability and upward mobility. This lack of services deepens existing poverty and inequality, creating cycles of disadvantage that are difficult to escape. Limited access to these vital services contributes to poorer health outcomes, lower educational achievement, and fewer job opportunities, which further isolates these neighborhoods from the broader urban economy.

Ultimately, disamenity zones not only reflect the immediate impacts of deindustrialization but also perpetuate and compound the economic and social challenges faced by urban residents, deepening the poverty and inequality within cities.

Urban Renewal Projects

Urban renewal projects are efforts by cities to revitalize areas that have faced economic decline or neglect. One common strategy is rezoning neighborhoods for mixed-use development, which integrates residential, commercial, and recreational spaces into a single area. Mixed-use zoning encourages walkable communities, reduces dependency on cars, and stimulates local economies by attracting diverse businesses and residents.

Redeveloping brownfields—properties previously used for industrial or commercial purposes that have been abandoned due to contamination or environmental hazards—is another significant urban renewal effort. Cleaning up and revitalizing these areas can transform neglected land into valuable community assets, creating jobs, improving environmental conditions, and attracting new investment into urban neighborhoods.

Inclusionary zoning and affordable housing policies are also crucial elements of urban renewal. These policies require developers to include affordable housing units in new residential projects, ensuring that lower-income residents are not displaced by rising housing costs. Inclusionary zoning helps maintain economic diversity within communities and provides stable, affordable housing options, thus counteracting some negative effects of gentrification.

Together, these strategies aim not only to revitalize urban spaces but also to build sustainable, equitable, and thriving communities for all residents.

Gentrification

Urban renewal projects, despite their positive intentions, can also accelerate gentrification—the process where redevelopment attracts wealthier residents into historically lower-income neighborhoods, often leading to displacement of existing residents. As cities rezone areas for mixed-use development or revitalize brownfields, neighborhoods can become more desirable, driving up property values and housing costs.

When property values rise, rent and home prices often follow, making neighborhoods unaffordable for long-term residents. New businesses, amenities, and improvements attract wealthier individuals who can pay higher housing costs, resulting in the displacement of lower-income residents. Over time, this demographic shift can change the neighborhood’s culture, identity, and social fabric, potentially alienating existing communities.

While inclusionary zoning and affordable housing policies aim to counteract these effects, they are not always sufficient to fully protect residents from displacement. Without comprehensive strategies that prioritize equity and community input, urban renewal projects can unintentionally deepen existing inequalities and exacerbate the very issues they seek to address.