Subsistence Agriculture

intensive & extensive subsistence agricultural practices

Economic Principles

agribusiness

commodity chain

economies of scale

Commercial Agriculture

intensive & extensive commercial agricultural practices

Effects & Trends

more vs less developed countries

family farms

human labor

carrying capacity

sizes of farms

Influence of Economic Forces

Among the many factors that influence farmers’ decisions are available capital and the relative costs of land and labor. Because of these different costs, farmers balance the use of their resources differently. If land is plentiful and costs little, they use it extensively. If land is scarce and expensive, they use it intensely. In reality, not every farm fits perfectly into one of these two categories.

Geographers often refer to the bid-rent theory when discussing land costs for different types of agricultural activities. There is usually a distance-decay relationship between proximity to the urban market and the value of the land, meaning the closer the land is to an urban center, the more valuable it is. The farmer willing to pay the highest price will gain possession of the land. Consequently, the farmer must use intensive agricultural practices to turn a profit on the land closest to the market.

Intensive land-use agriculture involves greater inputs of capital and paid labor relative to the space used. Intensive practices are used in various regions and conditions:

- Paddy rice farming in South Asia, Southeast Asia, and East Asia is very labor-intensive. Commonly used terraced fields make using machinery difficult.

- Truck farming in California, Texas, Florida, and near large cities is sometimes capital-intensive because it uses expensive machinery and other inputs. In addition to being capital-intensive, it is nearly always labor-intensive. These large farms produce very large quantities of vegetables and fruit, often relying on many low-paid migrant workers.

- Factory farming is a capital-intensive livestock operation in which many animals are kept in close quarters, bred, and fed in a controlled environment. The term comes from these operations running like a factory. Instead of cars or computers moving along an assembly line, it is the animals that progress from one end of the “factory” to the other end where they are eventually processed into meat products.

- Aquaculture (aquafarming) is a type of intensive farming where fish, shellfish, or water plants are raised in netted areas in the sea, tanks, or other bodies of water.

Extensive land-use agriculture uses fewer inputs of capital and paid labor relative to the amount of space used. Extensive practices, such as shifting cultivation, nomadic herding, and ranching, can be found throughout the world and across the entire spectrum of economic development.

Increasing Intensity

Regions of the world that traditionally relied on extensive agricultural techniques are under pressure because of local increases in demand for food, regional population growth, and global competition to use land more intensely. These demographic and economic forces have placed more stress on the land because they have pushed farmers to use land continuously, rather than allowing land to lie fallow and recover. This shift increases demand for expensive inputs such as irrigation, chemical fertilizers, and improved seeds.

Those who rely on shifting cultivation have found it more difficult to continue these methods as global demand for tropical cash crops competes for more land use. The timber industry has also put an economic strain on shifting cultivation. For subsistence farmers, increasing population and competition for space to grow timber, rubber, cotton, or products used in industry have resulted in food security issues, most noticeably in Africa.

Methods of Planting

Different methods of planting increase the intensity of land use. Double (or triple) cropping is planting and harvesting a crop two (or three) times per year on the same piece of land. Another technique, intercropping, also known as multicropping, is when farmers grow two or more crops simultaneously on the same field. For example, a farmer might plant a legume crop alongside a cereal crop to add nitrogen to the soil and guard against soil erosion.

The opposite of multicropping is monoculture, in which only one crop is grown or one type of animal is raised per season on a piece of land. Monocropping, or continuous monoculture, is only growing one type of crop or raising one type of animal year after year. As a result, these farmers purchase very specific equipment, irrigation systems, fertilizers, and pesticides designed for their one crop or animal to maximize efficiency.

Large-scale monocropping farms can cover thousands of acres dedicated solely to one crop, such as wheat, corn, rice, coffee, or cacao. While this approach can lead to lower per-unit production costs, higher yields, and increased profits, it also has negative impacts. These include soil depletion, decreased yields over time, increased reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and heightened risk since all of the farmer’s resources are invested in one crop.

The Meat Industry

The economic structure of livestock raising has undergone significant changes in recent decades. Global meat consumption increased by over 50 percent between 1998 and 2018, primarily due to population growth. This growing demand has accelerated the trend toward factory farms and centralized processing centers.

Today, cattle are less likely to graze on large expanses of land. Instead, they are raised in feedlots, also known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), where they have limited movement. This confinement allows the animals to grow bigger in a shorter period, maximizing space use and preparing them for slaughter quickly to maximize profits.

The global expansion of fast-food operations and increased meat demand has led to larger ranching operations in the United States and South America. In the US, competition for space, the desire for larger animals, and reduced raising time have contributed to the increased use of feedlots.

Some agricultural practices combine extensive and intensive phases. For example, raising cattle in Wyoming involves extensive farming where cattle roam and feed on grass in large ranches. As the cattle mature, they are transported to feedlots in northern Colorado for intensive fattening before being processed into meat for the market.

Commercial Agriculture and Agribusiness

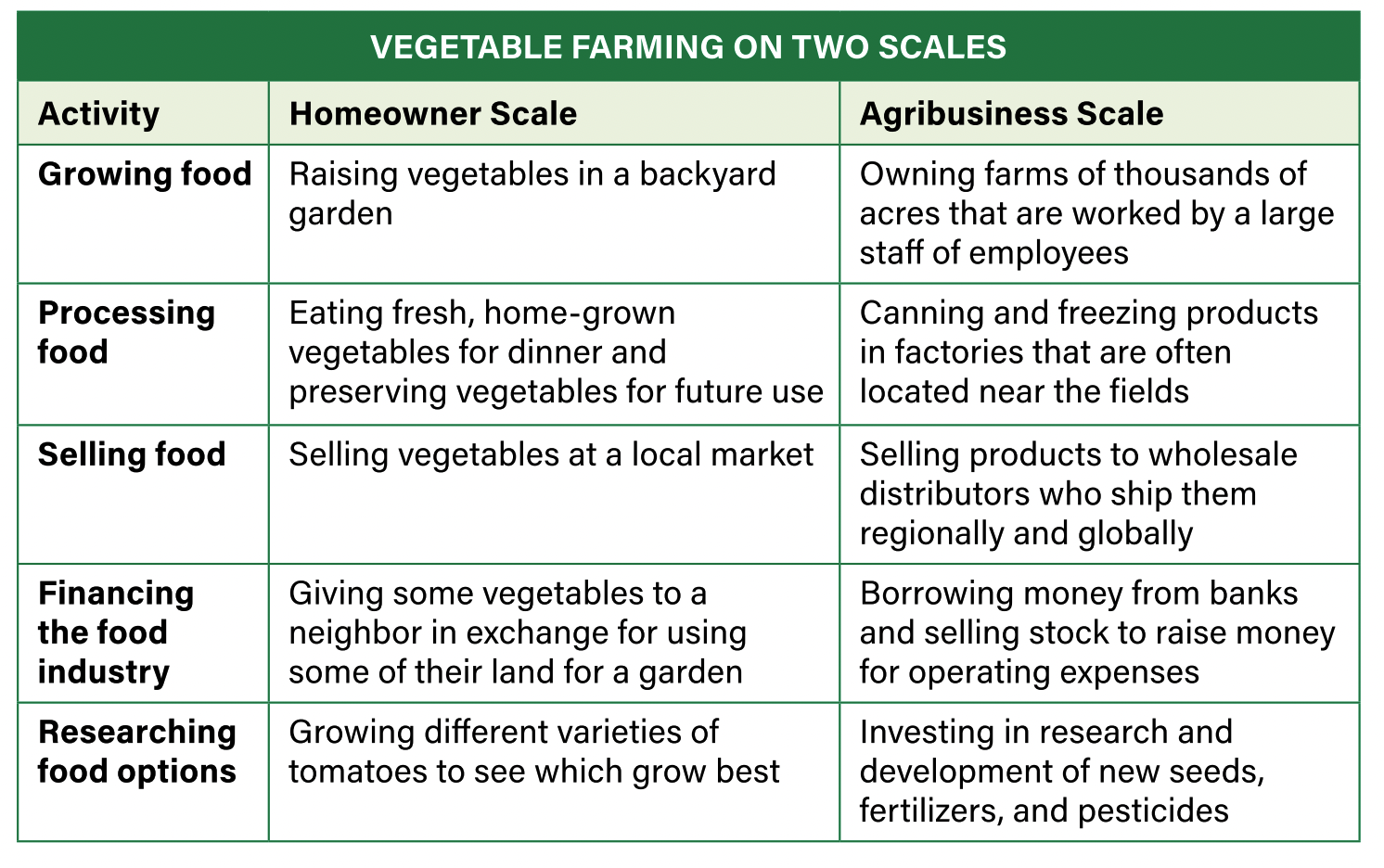

Agribusiness involves the integration of various steps of production in the food-processing industry such as research and development, processing and production, transportation, marketing, and retail of agricultural goods. Given the enormity of this system, the largest agribusinesses are owned by transnational corporations, or those that operate in many countries. These large-scale operations are commercial, highly mechanized, and often use chemicals and biotechnology in raising crops and animals. The following chart compares farming at the scale of a homeowner and an agribusiness.

Impact of Large-Scale Farms

Globalization has accelerated the growth of agribusiness and corporate farms during the latter half of the 20th century. Competition in agricultural products and services encouraged large-scale farms to operate more as a corporation than a family farm. Agribusinesses have often resulted from the consolidation of family farms, thus eliminating many small-scale farm operations. Many of the remaining family-owned farms have shifted to a corporate operating model. Often, large corporate farms practice vertical integration, or the ownership of other businesses involved in the steps of producing a particular good. Owning the contributing businesses gives the large farm more control of the variables and results in greater overall profits. Those businesses might include a research and development company that improves seeds, a trucking firm that transports farm products, a factory that processes the goods, and a wholesaler that distributes the food to stores.

Large-Scale Replacing Small-Scale Farms

Large-scale farms are usually specialized and practice monoculture. As farms become larger, more specialized, and vertically integrated, it becomes easier to take advantage of economies of scale, or an increase in efficiency to lower the per-unit production cost, resulting in greater profits. For example, consider a grain farmer who increases the size of his or her farm by purchasing an additional quarter section (160 acres). By using the existing machinery on the farm more efficiently, the farmer can successfully plant and harvest the additional acreage without the purchase of new equipment. This will increase the owner’s revenues while the expenses will not increase proportionally. As a result, the cost per unit of grain will decrease and profits will increase.

Larger farms can afford the latest technology, such as better seeds or machinery, and are more likely to produce greater profits through economies of scale. Large corporate farms have made it increasingly difficult for family farms to survive since they cannot compete with the significantly cheaper costs per-unit production of large-scale farming operations.

The success and efficiency of large farms has encouraged the World Bank to fund agribusiness ventures in the developing world, often at the expense of family and subsistence farmers. Also, many family farms in the periphery have disappeared because of the rising expenses associated with Green Revolution technology and the need to adopt this technology to survive and compete in an increasingly global market.

Commodity Chains and Consumption

The transformation of agriculture has resulted in a complex system that connected producers and consumers at a global scale. This complex and enormous system enabled someone who lives in a small American town to consume bananas from Ecuador, coffee from Ethiopia, chocolate from Switzerland, and cashews from Vietnam. This transformation may be attributed to advancements in biotechnology, mechanization, transportation, and food preservation.

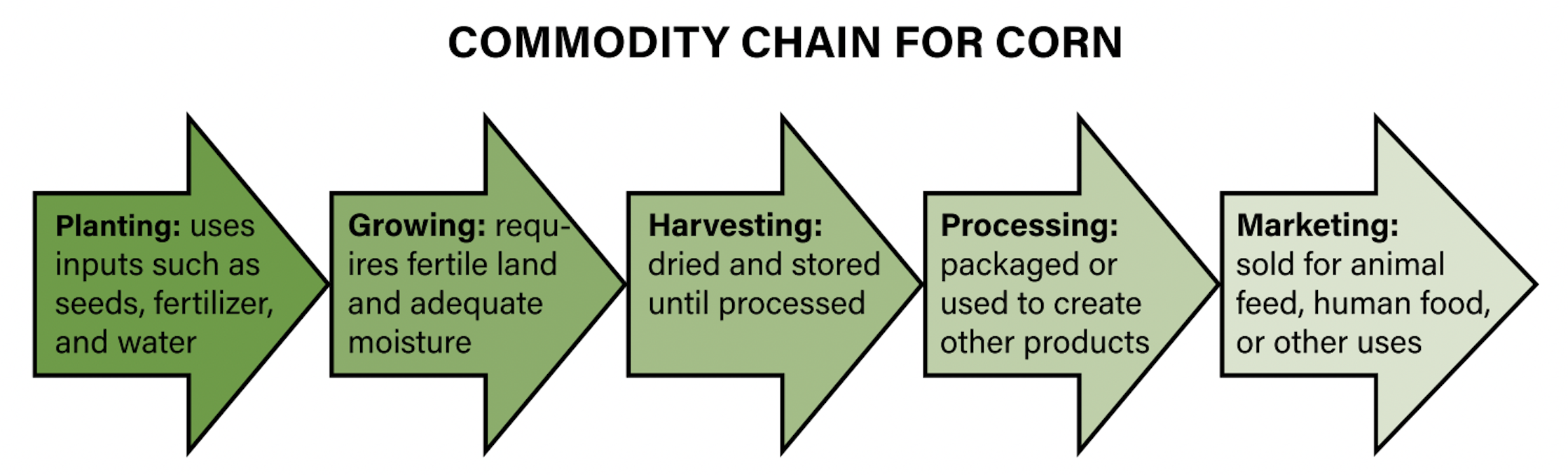

A commodity chain is a process used by corporations to gather resources, transform them into goods, and then transport them to consumers.

Improvements in agricultural technology, advances in transportation, and an increasingly globalized economy enable farmers to raise crops and animals far from their final market and allow consumers to still purchase the final products at low prices. Corn has numerous uses, such as livestock feed, sweetener, or fuel. Thus, the actual commodity chain of corn would be more specialized and complex than the one shown.

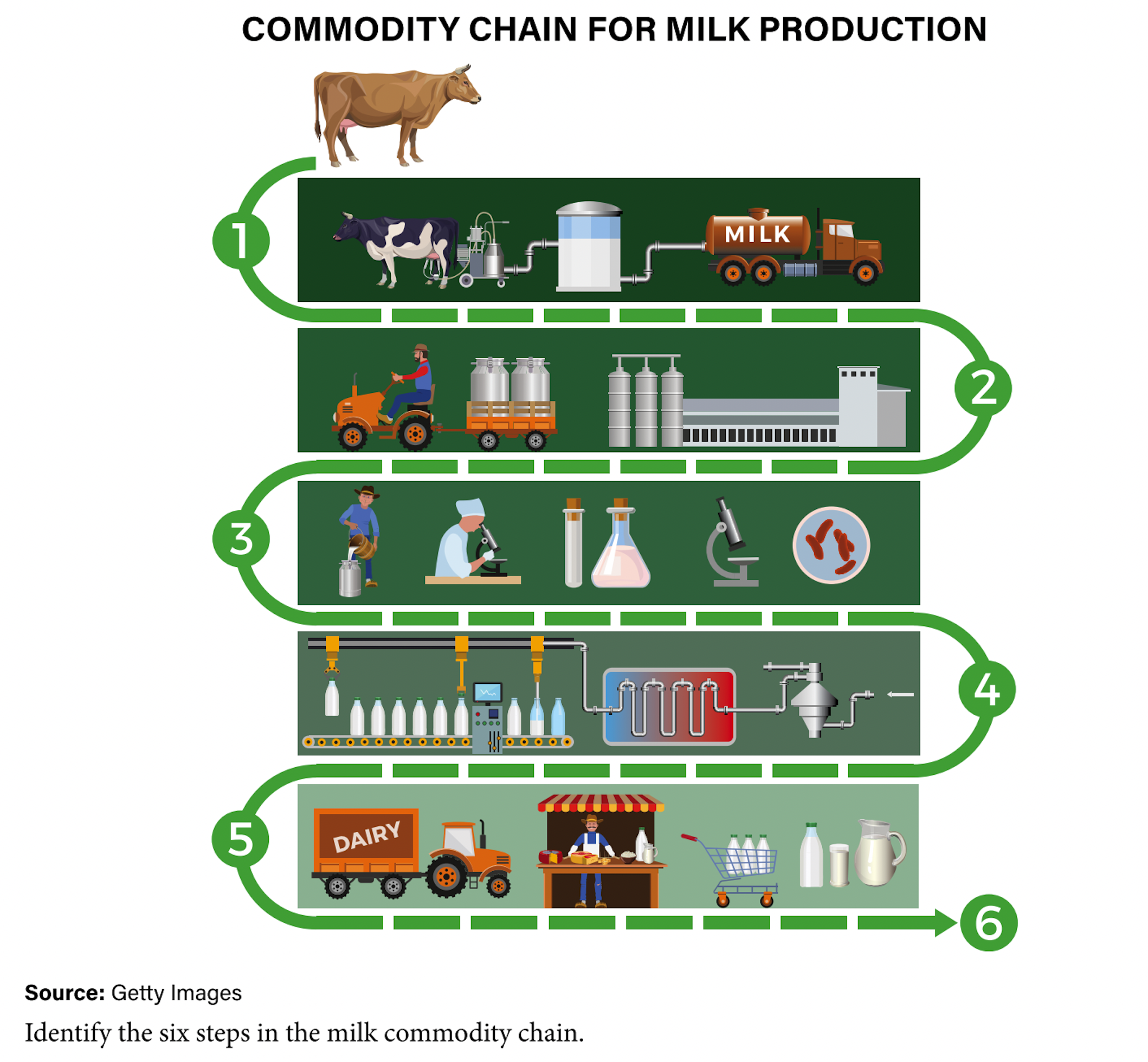

Additional elements of commodity chains that facilitate the process include financial institutions (banks), transportation companies, distributors, and governments. Each plays a key role in getting food from field to store. A detailed commodity chain shows the elements for milk production below.

Technological Improvements

The number of people that U.S. farmers can support given the available resources, or the carrying capacity, has risen tremendously over the past half century. In 1962, an average U.S. farmer fed an average of 26 people. Today, mostly due to technological advances, that figure has risen to 166 people. Farmers in the United States provide enough food to supply the needs of the nation, as well as many people in other parts of the world. Of course, there are other resources that are also necessary for life, such as clean air, water, and fuel.

Benefits Improvement in food production is attributed to technological advancements of the Second and Third Agricultural Revolutions. Improvements in the quality and the use of fertilizers, pesticides, insecticides, herbicides, irrigation, soil management, and farming equipment have all resulted in higher yields. A deeper understanding of the science of plants and animals has led to efficient selective breeding programs, hybrid seeds developed through the Green Revolution, and genetically modified organisms (GMOs) created through biotechnology. These developments have had a tremendous impact on the agricultural output of farmers.

Transportation and storage advances have allowed for the more extensive use of cool chains, which are transportation networks that keep food cool throughout a trip. Fruits and vegetables from the tropics can be delivered fresh to the temperate climates of North America and Europe at relatively low prices for consumers.

Costs Technological advancements have created some environmental damage. The loss of wetlands and large tracts of rainforest cleared to increase farmable land have led to the loss of biodiversity and water resources. Petroleum-based fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides have caused soil, water, and air pollution and threatened ecosystems.