Gender & Development

Global Gender Gap Index

The role of…

formal economy

informal economy

banking

micro loans

micro financing

Theories of Development

Rostow’s Stages of Development

Dependency Theory

Wallerstein’s World Systems Theory

commodity dependence

Females account for slightly less than half of the world’s population, yet they account for far less than half of the world’s earnings. Much of their work is not measured because it is unpaid work done for their family, such as raising children and cooking. When women do work in the formal sector, they are often paid less than their male counterparts. This loss of economic potential slows progress toward improving the standard of living. Many countries are trying to expand education for females so they can become fully engaged in economic development.

As countries become more developed economically, the roles open to women often change. In general, higher development and higher status for females are correlated. The Gender Inequality Index (GII) is often used to measure inequality and helps monitor changes in equity over time.

Barriers to Gender Equality

Within countries, urban areas often have higher gender equity than rural areas. Overall, conditions are improving but obstacles to gender equity for women still exist:

- Cultural barriers often inhibit participation in the economy.

- Lack of educational opportunities can reduce employment options.

- Limited access to loans and other resources makes starting or expanding a business difficult.

Wages for women have increased in recent decades, but there still is a global disparity in the wages between men and women, even with comparable work. In the United States, if a man and a woman do the same type of job, a man would typically make a salary that is 17.5 percent higher than a woman.

The Glass Ceiling Another trend reflecting employment discrimination toward women is that women rarely obtain upper-level jobs in companies, the civil service, or in governments, particularly in developing countries. The situation has been improving in recent years in developed countries, but the glass ceiling, as it is often called, remains. If a country reaches a stage where the glass ceiling ceases to exist, the standard of living will rise tremendously for all of its citizens.

In top levels of corporations and in politics, women often must overcome cultural attitudes that cause people to not see them as leaders. Women such as former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris, and General Motors Company CEO Mary Barra are examples of women who became part of the quinary sector.

Increased Opportunities for Women

Women have made progress toward gender equality despite the significant obstacles they face. Governments of many countries, transnational corporations, non-governmental organizations, and international organizations, such as the United Nations, have aided the efforts to reduce gender inequality.

Transnational Corporations

One reason for the expanded employment opportunities for women has been the efforts of transnational corporations. As these businesses have opened more factories in developing countries, they often employed women because they were available and would work for lower wages than men. Another key reason for increased female participation in the labor force is because of very low birth rates. Countries such as Japan and Singapore would face severe labor shortages if women were not accepted as an integral part of the labor force.

Increased educational opportunities for females during the past two decades also prepared more women to work outside their homes. Globally, more than 250 million additional women joined the paid workforce between 2006 and 2015. Many women who previously had low-paying domestic jobs as servants, childcare providers, and store clerks began earning significantly more in manufacturing jobs.

NGOs and Microloans

Several programs enacted by governments and international non-profit agencies, known as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), empower women to find jobs outside the home. One example of how NGOs have helped women is through microcredit, or microfinance programs, to provide loans often to women to start or expand a business. The most well-known of these is the Grameen Bank, founded in Bangladesh in 1983. These programs have been particularly active in South Asia and South America. The repayment rate for these loans has been unusually high—more than 98 percent.

The success of microcredit programs resulted in several changes to societies where the loans are available. The increased financial clout of women gave them more influence in their homes and communities. And as working women have more voice in childbearing decisions, more money to pay for contraceptives, and less need for additional children, birth rates have decreased. Women’s increased wealth also allows for the children to be better nourished, which has helped to reduce child mortality.

Sustainable Development Goals for Women

The United Nations established a series of goals in 2015 to encourage sustainable development. Many targeted areas to improve the lives of females. The creators of these goals recognized that gender equality will lead to economic development.

Theories of Development Inequality

Why have some countries of the world become so much wealthier than others? Geographers and others have proposed several theories of development to answer this question. Underlying it is a more general issue about equality. Can all countries grow equally prosperous, or will the world always include a mix of more- and less-wealthy countries?

Two of the best-known theories explaining these differences were developed by Walt Rostow and Immanuel Wallerstein.

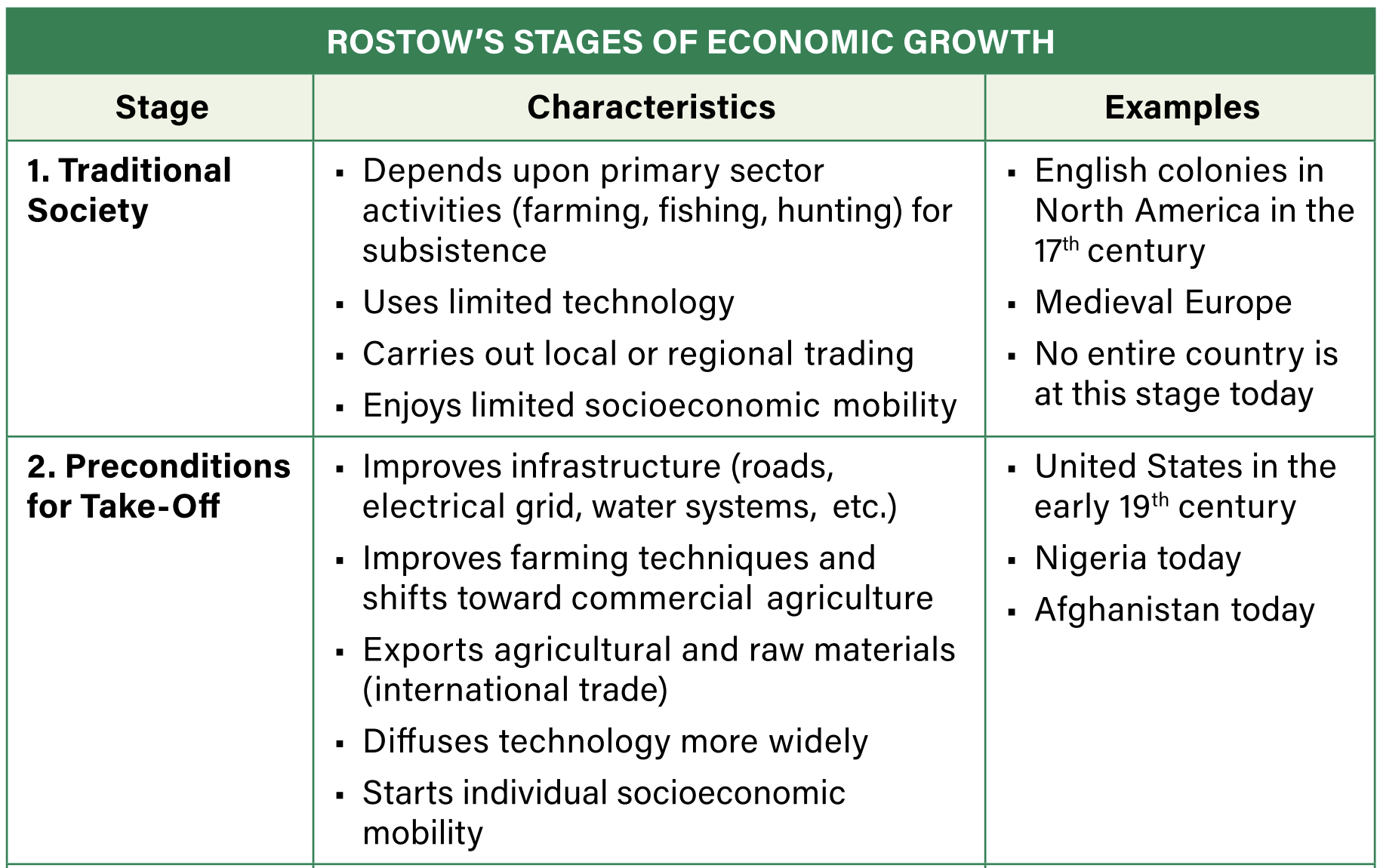

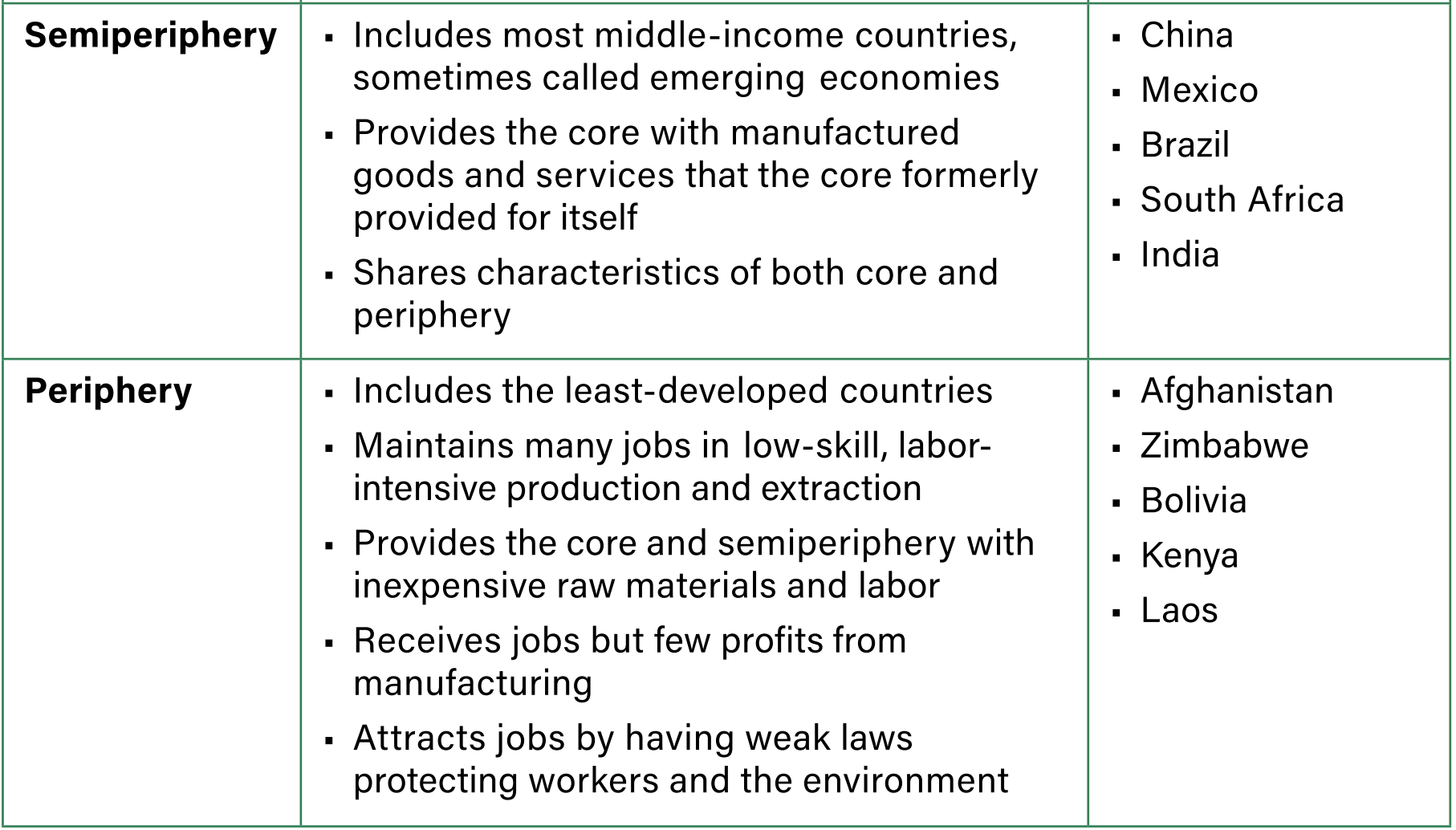

Rostow’s Stages of Economic Growth

In 1960, American economist Walt W. Rostow developed a modernization theory that focuses on the shift from traditional to modern forms of society.

He saw economic development as a linear progression in which countries moved from one stage to the next until they reached the fifth and final stage-high mass consumption.

Like the Demographic Transition Model (DTM), the Stages of Economic Growth theory is a generalization based upon how the United States and western Europe evolved, and both identify distinct stages. However, they differ fundamentally. The DTM is a population model that focuses on changes in the number of people in a country. Rostow’s theory is an economic model that focuses on how people live.

Rostow suggested that different inputs and levels of investment were required to allow countries to move from one stage to the next. The theory suggests a system for development-do this, then this, and eventually the economy of a country will become developed.

Criticisms of Rostow’s Model

In spite of being one of the most influential economic models of the 20th century, some experts have expressed concerns about Rostow’s model. Critics of Stages of Economic Growth model argue it has several weaknesses.

- Limited Examples: The model was based on American and European examples, so it did not fit countries of non-Western cultures or noncapitalist economies.

- Role of Exploitation: Rostow’s model led to poorer countries getting trapped in a state of dependency upon wealthier countries.

- Bias Toward Progress: The model suggested linear change, always in the direction of progress. However, developing countries often need the assistance, money, and technology of developed countries to develop. And in some cases, countries might regress in economic development.

- Lack of Variation: In his model, Rostow suggested all countries have the potential to develop, but there are significant differences among countries, such as physical size, population, natural resources, relative location, political systems, and climate, that affect their ability to develop.

- Lack of Sustainability: The model assumed that everyone could eventually lead a life of high mass consumption but failed to consider sustainable development or the carrying capacity of the earth.

- Need for Poorer Countries: Rostow’s model failed to recognize that most of the countries which reached the stage of high mass consumption did so by exploiting the resources of lesser-developed countries. Countries that were still developing would have difficulty finding other countries to exploit.

- Narrow Focus: The model focused on domestic economies and did not directly address interactions between countries, specifically globalization.

Despite these criticisms, geographers, economists, and others continue to use the model to understand how countries have changed over the past two centuries. It has prompted people to think about economic and social change in a global context and challenged them to provide their own framework.

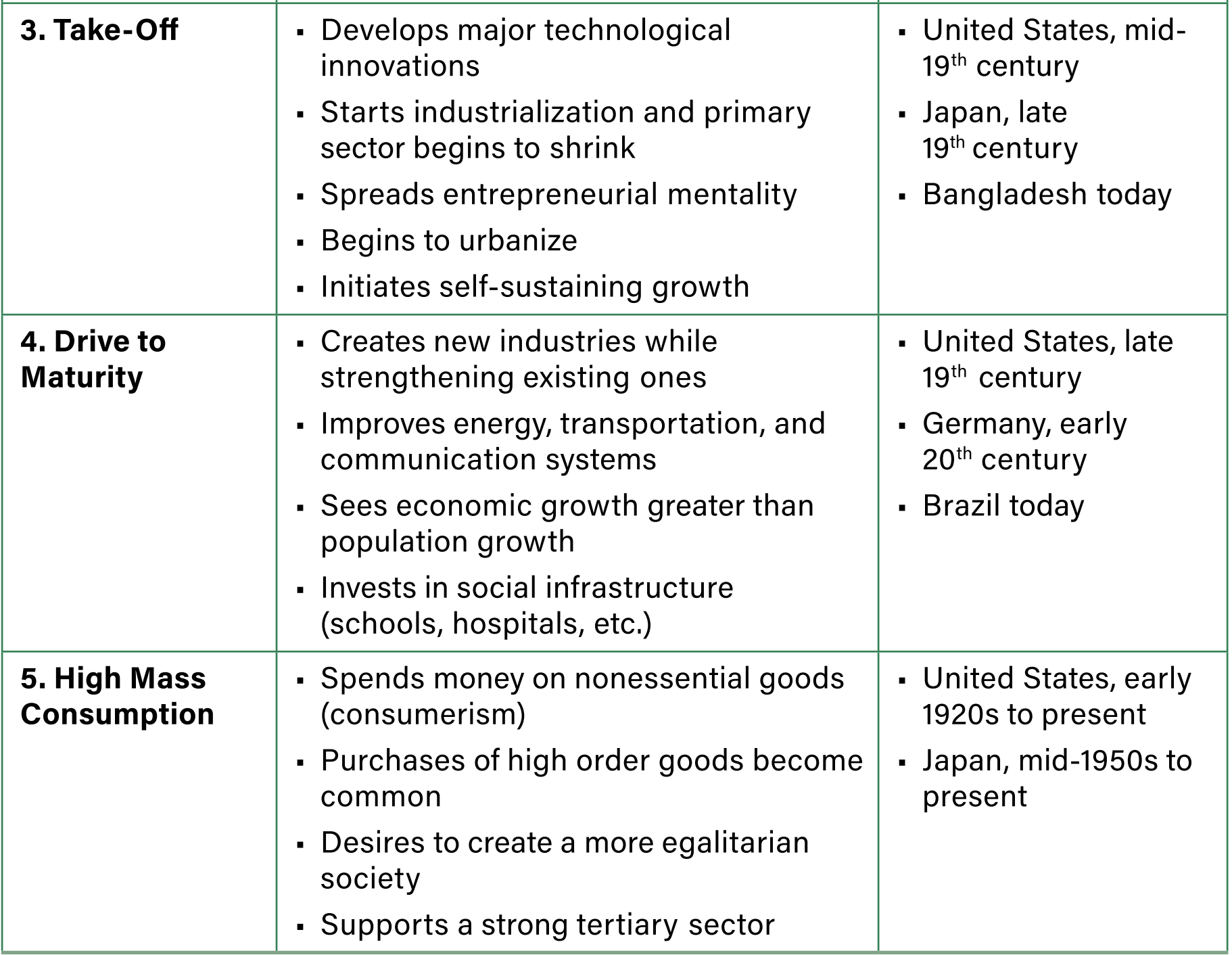

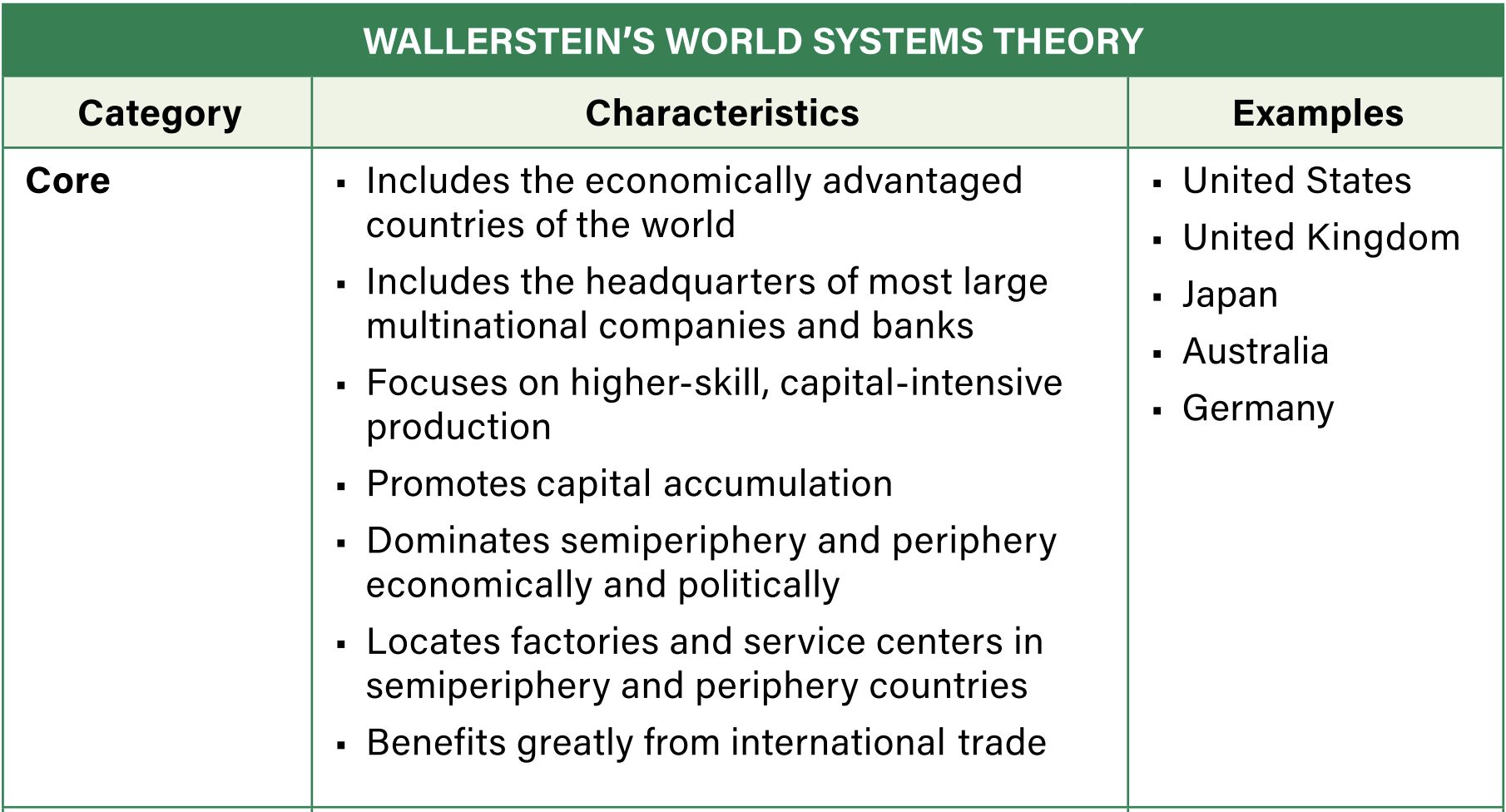

Wallerstein’s World Systems Theory

In the 1970s, historian Immanuel Wallerstein proposed an alternative model to Rostow’s, which he called the World Systems Theory. It is a dependency model, meaning that countries do not exist in isolation but are part of an intertwined world system in which all countries are dependent on each other.

Dependency theory argues that colonialism and neocolonialism are the cause of global inequities. Both Wallerstein and Rostow attempt to explain the inequalities that exist between different countries and regions. World Systems Theory includes both political and economic elements that have significant geographic impacts.

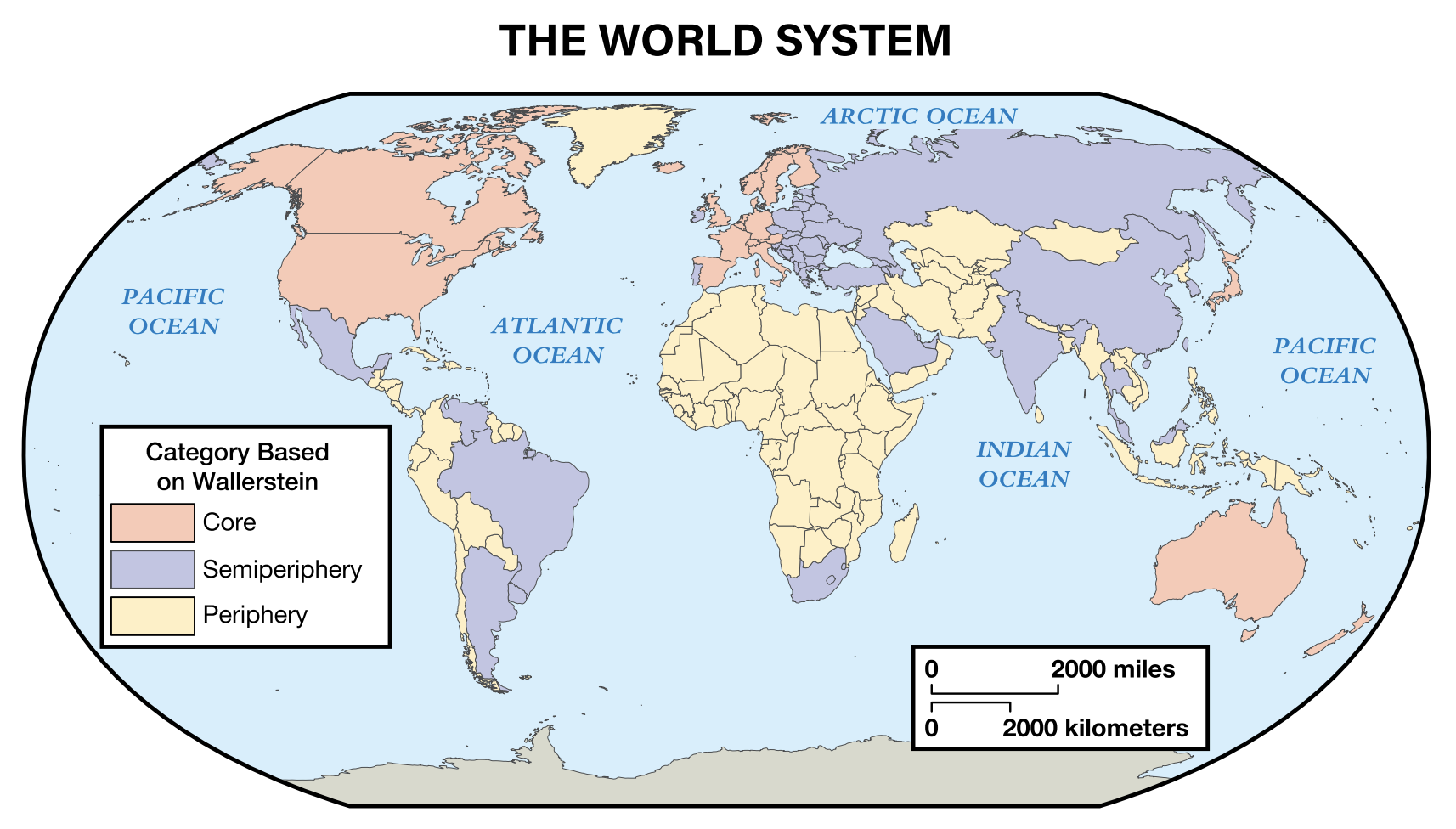

Wallerstein divided countries into three types-core, semiperiphery, and periphery. As a result, his theory is sometimes referred to as the Core-Periphery model.

Core Dominance

Multinational companies, financial institutions, and centers of technology are mostly based in core countries, but they have significantly influenced the economies of semiperiphery and periphery countries. Businesses and governments in non-core countries borrow money to finance large-scale projects and purchase technology from core countries. Both processes increase the dependency of the periphery on the core.

Changing Categories

Unlike Rostow’s model, Wallerstein’s model does not suggest that all countries can reach the highest level of development, nor does it explain how countries can improve their position. In contrast, it indicates that the world system will always include a combination of types of countries. But countries can change categories, moving in or out of the core. For example, in 1950, South Korea and Singapore were part of the periphery. By 2020, they were core countries. In 1900, Argentina was a core country. By 2000, it had become part of the semiperiphery.

Labor Trends

Wallerstein’s model provides a framework for analyzing the international division of labor by sector and location:

- Periphery countries are often where primary sector workers engaged in the extraction of raw materials and agriculture are located.

- Semiperiphery countries are often home to many workers in the secondary sector (such as factory workers) and in the tertiary sector (such as call center staff).

- Core countries include many tertiary sector workers and most quinary and quaternary sector workers.

Systems Theory at the Country Scale

Wallerstein built his model for a global scale. However, geographers also apply it to smaller scales by identifying centers of power and dependency relationships. In the United States the core would be the major cities, such as New York and Chicago. The semiperiphery would be the manufacturing belt in the Midwest and parts of the South. The periphery would be the rural areas of the Great Plains and the West.

Criticisms of World Systems Theory

- Little Emphasis on Culture It focused heavily on economic influence-investments and purchases of raw materials- but it paid little attention to the pervasive influence of culture- movies, music, and television.

- Emphasis on Industry It was based on industrial production, but many countries have postindustrial economies based on providing services.

- Lack of Explanation It is of limited practical use, suggesting that countries can change their status, but it does not explain how.

- Limited Roles It focused too much on the role of countries, governments, and corporations. As a result, it failed to recognize the role of organizations such as UN agencies and private, nonprofit charitable NGOs.

Commodity Dependence

Core countries have diversified export economies that rely on a variety of goods and services. In contrast, some semiperiphery and many periphery countries rely heavily on the export of commodities, raw materials such as coffee, cocoa, and oil, that have not undergone any processing. A country has commodity dependence when more than 60 percent of its exports are raw materials.

Since the value of commodities rise as the degree of processing increases, the businesses and countries exporting unprocessed raw materials receive relatively low returns. As a result, there is a very strong correlation between commodity dependence and low levels of economic development.

More than half of the countries in the world are commodity dependent. They are most common in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean region. Commodity-dependent countries (CDCs) are vulnerable to fluctuating commodity prices. Prices can suddenly drop for many reasons:

- a large, new supply of the commodity becomes available

- manufacturing companies find a less-expensive substitute product

- consumer demand for the product made from the commodity falls

Some commodities, such as oil, are much more valuable than others. Even valuable commodities are vulnerable to wide, rapid price fluctuations. Between 2012 and 2020, the price of a barrel of oil dropped from $109 down to $41, then rose up to $70 before falling to $42.

The countries that have best weathered a downturn in oil prices have been those that have diversified their exports. For example, the United Arab Emirates was very dependent on oil revenues in the 20th century. The country’s leaders recognized the risk in this and began to diversify its economy by expanding its transportation, financial, and tourist sectors, particularly in its major city, Dubai. When oil prices crashed around 2014, the country’s economy was varied enough to withstand the potentially disastrous decline.