Need to Know:

judicial review

precedent

stare decisis

judicial activism

judicial restraint

ideological makeup of the court

two interpretations of the constitution

Courts:

Warren Court

Burger Court

Rehnquist Court

Roberts Court

Checks on the Court:

Congress

Executive Branch

A Court Dedicated to Individual Liberties

In the post-World War II years, the Court protected and extended individual liberties. It delivered mixed messages on civil liberties up to this point – holding states to First Amendment protections while allowing government infringements in times of national security threats. For example, it upheld FDR’s executive order that placed Japanese Americans in internment camps after the Japanese attack in 1941. After that, however, the Court followed a fairly consistent effort to protect individual liberties and the rights of accused criminals. The trend crested in 1973 when the Court upheld a woman’s right to an abortion in Roe v. Wade.

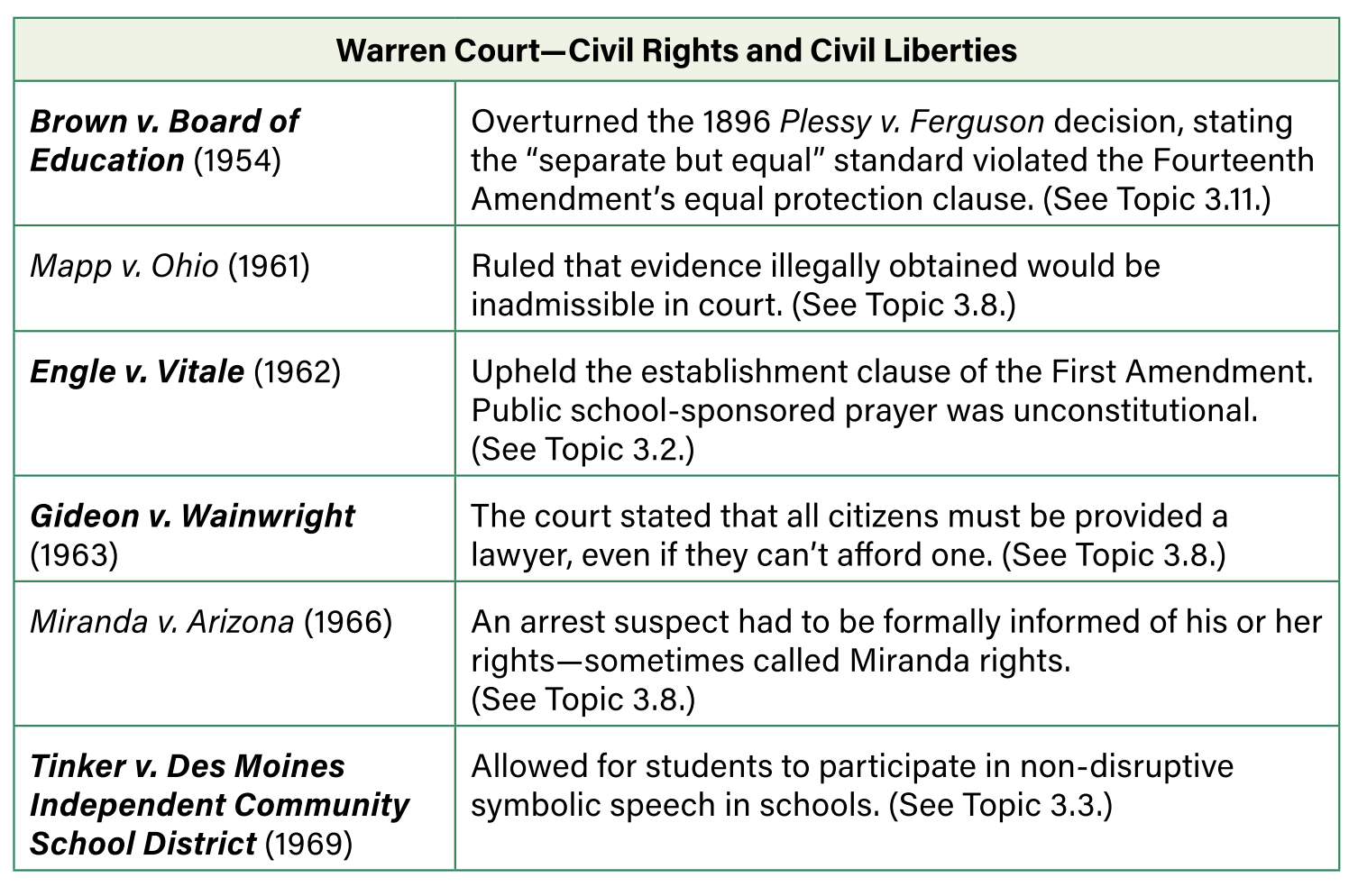

The Warren Court

The Court extended many liberties under Chief Justice Earl Warren after President Dwight Eisenhower appointed him in 1953. As attorney general for California during the war, Warren oversaw the internment of Japanese Americans, and in 1948, he was the Republican vice-presidential nominee. But any expectations that Warren would act as a conservative judge were lost soon after he took the bench.

Warren’s legacy did not please traditionalists because his Court overturned state policies created by democratically elected legislatures. The controversial or unpopular decisions led some people to challenge the Court’s legitimacy. Several Warren Court decisions seemed to insult states’ political cultures and threaten to drain state treasuries. Some argued that Earl Warren should be impeached. The Warren Court had made unpopular decisions, but it had not committed impeachable acts – such as taking bribes or failing to carry out the job – so only justices’ retirements or deaths could change the Court’s makeup.

The Burger Court

President Richard Nixon won the 1968 election, partly by criticizing Warren’s Court as detrimental to law enforcement and local control. When Chief Justice Earl Warren retired, Nixon appointed Warren Burger, a U.S. appeals court justice, as his replacement. Burger, however, did not fully align with Nixon’s conservative goals and struggled with judicial leadership, lacking Warren’s effectiveness in guiding the Court.

In Roe v. Wade, Burger joined six other justices to rule against or modify state anti-abortion laws, asserting a violation of due process and establishing a woman’s unconditional right to abortion during the first trimester of pregnancy. He also authored a unanimous opinion upholding court-ordered school busing to achieve racial integration.

Burger faced challenges in achieving majority opinions, often leaving cases undecided and increasing the Court’s workload to handle up to 150 appeals per year. His tenure was marked by criticism from within and outside the Court, with some describing him as intellectually lacking and alienating his colleagues. By 1986, Burger retired, expressing little sentiment about leaving the Court.

The Rehnquist Court

Upon Burger’s retirement, President Reagan elevated Associate Justice William Rehnquist to Chief Justice. Rehnquist, known for his strict constructionist views, had faced scrutiny during his nomination, accused of racism due to his earlier stance supporting “separate but equal.”

Initially dissenting frequently and dubbed “the Lone Ranger,” Rehnquist’s leadership saw improvements in the Court’s conference procedures and a reduction in its caseload. Both conservative and liberal justices appreciated these changes. During the 1990s, the Rehnquist Court notably upheld states’ rights to impose restrictions on abortion and limited Congress’s authority under the commerce clause, reflecting a broader ideological shift.

Legislating After Unfavorable Decisions

While Supreme Court decisions are generally final, constitutional amendments can alter their impact. For instance, the Eleventh Amendment was ratified in response to the Supreme Court’s decision in Chisolm v. Georgia (1794), which allowed federal courts to hear lawsuits against states. The amendment prohibits federal courts from hearing certain lawsuits against states, shielding them from certain legal challenges.

Similarly, the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified after the Civil War, overturned the Dred Scott decision by ensuring citizenship and equal protection under the law for all individuals born in the United States. Another example is the Sixteenth Amendment (1913), which enabled Congress to levy an income tax, overcoming earlier Supreme Court decisions that had struck down such taxes.

These amendments illustrate how constitutional change can respond to and modify the implications of Supreme Court rulings, shaping American legal and political history.

Amending the Constitution represents the most definitive method to counteract Supreme Court decisions, although it’s a challenging process. Recent movements aimed at amending the Constitution to restrict abortions, prohibit same-sex marriage, and criminalize flag burning have all failed, illustrating the difficulty of achieving such changes through this route. A more practical approach often involves Congress or state legislatures passing revised laws that address the concerns raised by Supreme Court rulings but in a slightly different legal form.

Implementation of Supreme Court decisions involves translating judicial rulings into practical actions. While courts issue orders, decrees, or injunctions to direct specific actions or prevent others, they lack the means to enforce these mandates independently. Instead, enforcement typically requires cooperation from other branches of government such as the executive branch, U.S. marshals, regulatory agencies, or even the military.

Historically, there have been instances where the executive branch has resisted or delayed compliance with Supreme Court rulings. For example, President Andrew Jackson famously opposed a Supreme Court decision regarding Cherokee Indian lands, reportedly stating, “John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it.” Similarly, during the 1950s, federal troops were deployed to enforce the integration of a Little Rock high school following a Supreme Court ruling, illustrating the executive branch’s role in implementing contentious judicial decisions.

Overall, while the Supreme Court holds significant authority in interpreting the law, its decisions rely on cooperation from other branches of government to ensure effective implementation and enforcement across the United States.

Judicial Activism vs. Judicial Restraint

Ever since the Supreme Court first exercised judicial review in Marbury, it has reserved the right to rule on government action in violation of constitutional principles, whether by the legislature or the executive. Judicial review has seemingly placed the Supreme Court, as Brutus predicted, above the other branches, making it the final arbiter on many controversies. On many topics, as Brutus No. I warned, it has made the federal government supreme while defining what states, Congress, and the president can or cannot do. On other topics, it has restrained the federal government.

When judges strike down laws or reverses public policy, they are exercising judicial activism. (To remember this concept, think judges acting to create the law.) Activism can be liberal or conservative, depending on the nature of the law or executive action that is struck down. When the Court threw out the New York maximum-hours law in 1905 in Lochner, it acted conservatively because it rejected an established liberal statute. In Roe v. Wade, the Court acted liberally to remove a conservative anti-abortion policy in Texas. Courts at multiple levels in both the state and federal systems have struck down statutes as well as presidential, departmental, and agency decisions.

The Court’s power to strike down parts of, or entire laws, has encouraged litigation and changes in policy. For example, gun owners and the National Rifle Association (NRA) supported an effort to overturn a ban on handguns in Washington, DC and got a victory in the Heller decision. (See Topics 3.5 and 3.7.) Several state attorneys general who opposed the Affordable Care Act sued to overturn it. In a 5:4 decision, in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012), the Court upheld the key element of the Affordable Care Act, the individual federal mandate that requires all citizens to purchase health insurance or pay a penalty. In striking down limits on when a corporation can advertise during a campaign season, it struck down parts of Congress’s Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (2002) in Citizens United v. FEC (2010).

Critics of judicial activism tend to point out that, in a democracy, elected representative legislatures should create policy. These critics advocate for judicial restraint. Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone first used the term in his 1936 dissent when the majority outlawed a New Deal program. The Court should not, say these critics, decide a dispute in that manner unless there is a concrete injury to be relieved by the decision. Strict constructionist Antonin Scalia once claimed, “A living Constitution judge [is] a happy fellow who comes home at night to his wife and says, “The Constitution means exactly what I think it ought to mean!'” Justices should not declare a law unconstitutional, strict constructionists say today, when it merely violates their own idea of what the Constitution means in a contemporary context, but only when the law clearly and directly contradicts the document. To do otherwise is “legislating from the bench,” say strict constructionists. This ongoing debate about judicial activism and restraint has coincided with discussions about the Court’s role in shaping national policy.

Still other critics argue that judicial policymaking is ineffective as well as undemocratic. Wise judges have a firm understanding of the Constitution and citizens’ rights, but they don’t always study issues over time. Most judges don’t have special expertise on matters of environmental protection, operating schools, or other administrative matters. They don’t have the support systems of lawmakers, such as committee staffers and researchers, to fully engage an issue to find a solution. When courts rule, the outcome is not always practical or manageable for those meant to implement it. Additionally, many such court rulings are just unpopular, and with judges’ life tenures, there’s no recourse for the citizenry.

Presidential Appointments and Senate Confirmation

With hundreds of judgeships in the lower courts, presidents will have a chance to appoint judges to the federal bench over their four or eight years in office. When a vacancy occurs, or when Congress creates a new seat on an overloaded court, the president carefully selects a qualified judge because that person can shape law and will likely do so until late in his or her life.

Senate’s Advice and Consent

The Senate Judiciary Committee reviews the president’s judicial appointments. Sometimes nominees appear before the committee to answer senators’ questions about their experience or their views on the law. Less controversial district judges are confirmed without a hearing based largely on the recommendation of the senators from the nominee’s state.

The more controversial, polarizing Supreme Court nominees will receive greater attention during sometimes contentious and dramatic hearings.

The quick determination of an appointee’s political philosophy has become known as a “litmus test.” Much like quickly testing a solution for its pH in chemistry class, someone trying to determine a judicial nominee’s ideology on the political spectrum will ask a pointed question on a controversial issue or look at one of the nominee’s prior opinions from a lower court. Presidents, senators, or pundits can conduct such a “test.” The very term has a built-in criticism, as a judge’s complex judicial philosophy should not be determined as quickly as a black-and-white scientific measurement.

Senatorial Courtesy

The Senate firmly reserves its right of advice and consent. “In practical terms,” said George W. Bush administration attorney Rachel Brand, “the home state senators are almost as important as—and sometimes more important than—the president in determining who will be nominated to a particular lower-court judgeship.” This practice of senatorial courtesy is especially routine with district judge appointments, as districts are entirely within a given state. When vacancies occur, senators typically recommend judges to the White House.

Senate procedure and tradition give individual senators veto power over nominees located within their respective states. For U.S. district court nominations, each of the two senators receives a blue slip—a blue piece of paper they return to the Judiciary Committee to allow the process to move forward. To derail the process, a senator can return the slip with a negative indication or never return it at all. The committee chair will usually not hold a hearing on the nominee’s confirmation until both senators have consented.

This custom has encouraged presidents to consult with the home-state senators early in the process. All senators embrace this influence. They are the guardians and representatives for their states. The other 98 senators tend to follow the home state senators’ lead, especially if they are in the same party, and vote accordingly.

This custom is somewhat followed with appeals court judges as well.

Confirmation

When a Supreme Court vacancy occurs, a president has a unique opportunity to shape American jurisprudence. Of the 162 nominations to the Supreme Court over U.S. history, 36 were not confirmed. Eleven were rejected by a vote of the full Senate. The others were either never acted on by the Judiciary Committee or withdrawn by the nominee or by the president. Few confirmations brought rancor or public spectacle until the Senate rejected two of President Nixon’s nominees. Since then, the Court’s influence on controversial topics, intense partisanship, the public nature of the contentious confirmation process, and contentious hearings have highlighted the divides between the parties.

Interest Groups

The increasingly publicized confirmation process has also involved interest groups. Confirmation hearings were not public until 1929. In recent years, they have become a spectacle and may include a long list of witnesses testifying about the nominee’s qualifications. The most active and reputable interest group to testify about judicial nominees is the American Bar Association (ABA). Since the 1950s, this association of lawyers has been involved in the process. They rate nominees as “highly qualified,” “qualified,” and “not qualified.” More recently, additional groups weigh in on the process, especially when they see their interests threatened or enhanced. Interest groups also target a senator’s home state with ads urging voters to contact their senators in support of or in opposition to the nominee. Indeed, interest groups sometimes suggest or even draft questions for senators to assist them at the confirmation hearings.

Getting “Borked”

The confirmation process began to focus on ideology during the Reagan administration. President Reagan nominated U.S. Appeals Court Judge Robert Bork for the Supreme Court in 1987. He was an advocate of original intent, or “Originalism,” seeking to uphold the Constitution as the framers intended. He made clear that he despised the rulings of the activist Warren Court. When asked about his nomination, then-Senator Joe Biden, chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, warned the White House that choosing Bork would likely result in a confirmation fight. Senator Edward Kennedy drew a line in the sand at a Senate press conference. “Robert Bork’s America,” Kennedy said, “is a land in which women would be forced into back alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in midnight raids, and schoolchildren could not be taught evolution.” Kennedy’s warning brought attention to Judge Bork’s extreme views that threatened to turn back a generation of civil rights and civil liberties decisions.

After hearings with the committee, the full Senate, which had unanimously confirmed Bork as an appeals court judge in 1981, rejected him by a vote of 58 to 42. The term “to bork” entered the American political lexicon, defined more recently by the New York Times: “to destroy a judicial nominee through a concerted attack on his character, background, and philosophy.”

Clarence Thomas

In 1991, President Bush announced his replacement for retiring Justice Thurgood Marshall, the first African American on the Court. He nominated conservative U.S. Appeals Court judge Clarence Thomas, who, as an African American, reflected the left’s desire for diversity and the right’s desire for a strict constructionist.

Several concerns about Thomas’ appointment arose. Thomas was known for very conservative views, causing liberals to take issue with his ideology. He had served as a district appeals judge for only about a year before his nomination, leading some to question Thomas’ experience.

Then Anita Hill, a former employee of Thomas, came forward with accusations against him of sexual misconduct. The Judiciary Committee invited her to testify. In a highly televised carnival atmosphere, Hill testified for seven hours about the harassing comments Thomas had made and the pornographic films he discussed. Thomas denied all the allegations and called the hearing a “high-tech lynching.” After a tie vote in an all-white male judiciary committee, the full Senate barely confirmed Thomas.

“The Nuclear Option”

During George W. Bush’s first term, Democrats did not allow a vote on 10 of the 52 appeals court nominees that had cleared the Judiciary Committee. Conservative nominees were delayed by Senate procedure. The Democrats, in the minority at the time, invoked the right to filibuster votes on judges. One Bush nominee waited four years.

Bush declared in his State of the Union message, “Every judicial nominee deserves an up or down vote.” Senate Republicans threatened to change the rules to disallow the filibuster, which could be done with a simple majority vote. The threat to the filibuster became known as a drastic “nuclear option.” The nuclear option was averted when a bipartisan group of senators dubbed the “Gang of 14” joined forces to create a compromise that kept the Senate rules the same while confirming most appointees.

Denying Garland

In February 2016, Justice Antonin Scalia died. Republican presidential candidates in the primary race agreed on one thing: the next president should appoint Scalia’s replacement. With Democratic President Obama in his final year on the job, Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell announced that the Senate would not hold a vote on any nominee until the voters elected a new president. A month later, with ten months remaining until a new president would be sworn in, Obama nominated Judge Merrick Garland to replace Scalia. Garland was a judicial selection from the DC Circuit with a unanimous “well-qualified” rating from the ABA. Senator McConnell’s decision was strategic if unusual, and he kept his promise to use “the nuclear option,” to the dismay of many. Vacancies on the Supreme Court do occur, and the Court can operate temporarily with eight members, but to ensure the vacancy for more than ten months was unprecedented.

Constitutionally, nothing mandates a timeline on the Senate’s confirmation process. In the end, Donald Trump won the presidency, Republicans retained control of the Senate, and Trump nominated Tenth Circuit Judge Neil Gorsuch within two weeks of his inauguration. The Senate confirmed Gorsuch by a vote of 54 to 45.