Need to Know:

selective incorporation

All levels of government adhere to most elements of the Bill of Rights, but that wasn’t always the case. The Bill of Rights was ratified to protect the people from the federal government. The document begins with the First Amendment addressing what the government cannot do. “Congress shall make no law” that violates freedoms of religion, speech, press, and assembly. The document then goes on to address additional liberties Congress cannot take away. Most states had already developed bills of rights with similar provisions, but states did not originally have to follow the national Bill of Rights because it was understood that the federal Constitution referred only to federal laws, not state laws.

Incorporating the Bill of Rights

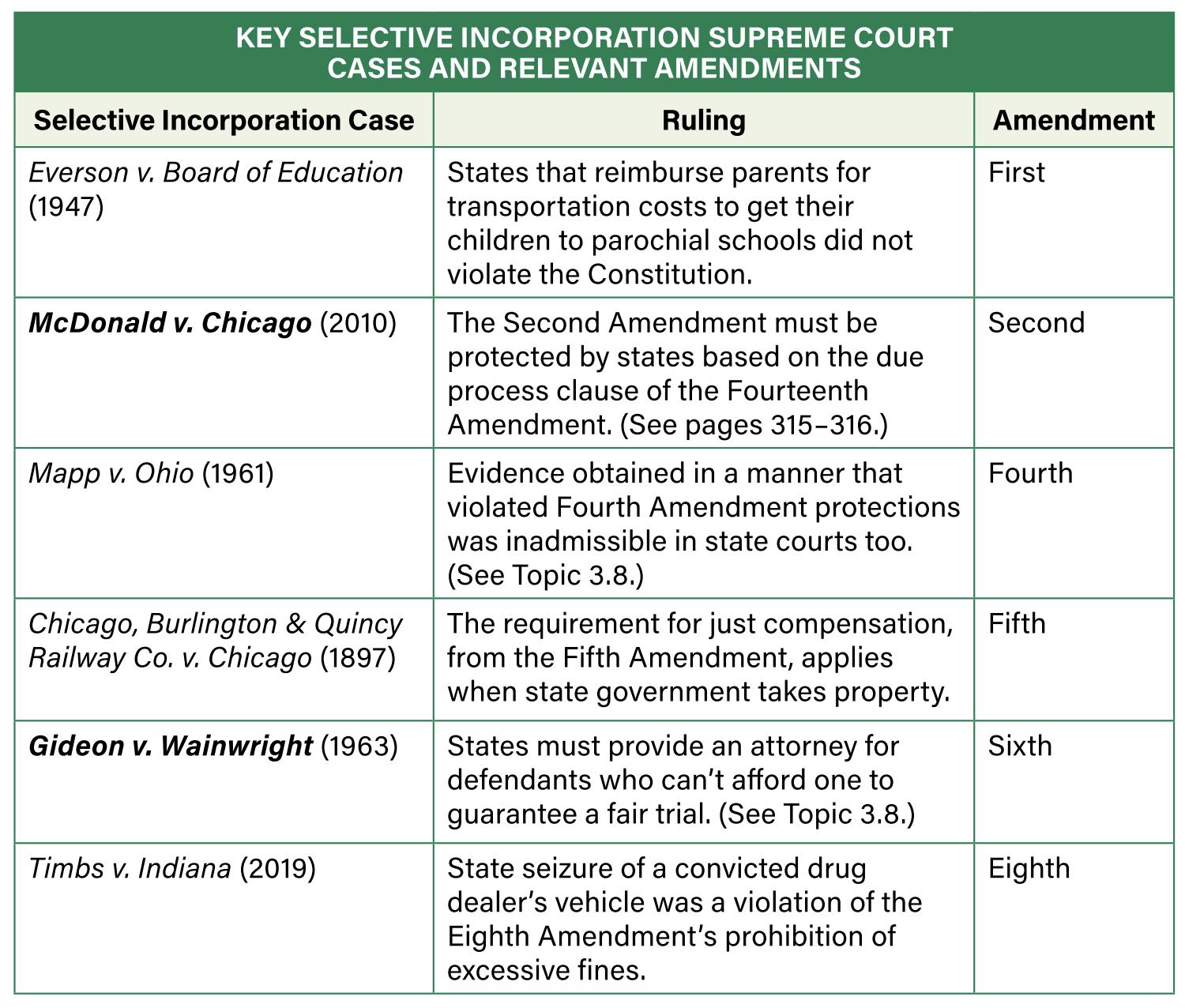

The Supreme Court has ruled in landmark cases that state laws must also adhere to certain Bill of Rights provisions through the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause. The process of declaring only certain, or selected, provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states rather than all of them at once is known as selective incorporation.

The concept of fundamental fairness that ensures legitimate government in a democracy is due process. It prevents arbitrary government decisions to avoid mistaken or abusive taking of life, liberty, or property (including money) from individuals without legal cause.

The question of whether the Bill of Rights limited the federal government only, or also the states, was originally answered in the 1833 case Barron v. Baltimore. Justice John Marshall’s Court made clear that states, if not restrained by their own constitutions or bills of rights, did not have to follow the federal Bill of Rights.

Fourteenth Amendment

Decades after the Barron case, the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) in the aftermath of the Civil War strengthened due process. Before and during the Civil War, southern states placed many restrictions on the basic liberties of African Americans and white citizens who tried to defend African American rights. After the war, Union leaders questioned if Southern states would comply with new laws that protected due process, especially for former slaves. Would an accused African American man receive a fair and impartial jury at his trial? Could an African American defendant refuse to testify in court, as a white person could? To ensure the states followed these commonly accepted principles in the federal Bill of Rights and in most state constitutions, Republicans in the House of Representatives drafted the most important and far-reaching of the Reconstruction Amendments, the Fourteenth. It declares that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States … are citizens” and that no state can “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Early Incorporation

The first incorporation case used due process to evaluate issues of property seizure. In the 1880s, a Chicago rail line sued the city, which had constructed a street across its tracks. In an 1897 decision, the Court held that the newer due process clause compelled Chicago to award just compensation when taking private property for public use. This ruling incorporated the just compensation clause of the Fifth Amendment, requiring that the states adhere to it as well.

Incorporation and the First Amendment Later, the Supreme Court declared that the First Amendment prevents states from infringing on free thought and free expression. In a series of cases that addressed state laws designed to crush radical ideas and sensational journalism, the Court began to hold states to First Amendment standards. In the 1920s, Benjamin Gitlow, a New York Socialist, was arrested and prosecuted for violating the state’s criminal anarchy law. The law prevented advocating a violent overthrow of the government. Gitlow was arrested for writing, publishing, and distributing thousands of copies of pamphlets called the Left Wing Manifesto that called for strikes and “class action … in any form.”

In one of its first cases, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) appealed his case and argued that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment compelled states to follow the same free speech and free press ideas in the First Amendment as the federal government. In Gitlow v. New York (1925), however, the Court actually enhanced the state’s power by upholding the state’s criminal anarchy law and Gitlow’s conviction because Gitlow’s activities represented a threat to public safety. The court felt the substantive reason for the state’s limitation of Gitlow’s message was justified to preserve order. Nonetheless, the Court did address the question of whether or not the Bill of Rights did or could apply to the states. In the majority opinion, the Court said, “For present purposes, we may and do assume that freedom of speech and of the press .. are among the fundamental personal rights and liberties’ protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from impairment by the States.” In other words, Gitlow’s free speech was not protected because it was a threat to public safety, but the Court did put the states on notice.

The Court applied that warning in 1931. Minnesota had attempted to bring outrageous and obnoxious newspapers under control with a public nuisance law, informally dubbed the “Minnesota Gag Law.” This statute permitted a judge to stop obscene, malicious, scandalous, and defamatory material. A hard-hitting paper published by the controversial J.M. Near printed anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic, anti-Black, and anti labor stories. Both the ACLU and Chicago newspaper mogul Robert McCormick came to Near’s aid, not for his beliefs, but on anti-censorship principles. The Court did too. In Near v. Minnesota it declared that the Minnesota statute “raises questions of grave importance. It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” In this ruling, through the doctrine of selective incorporation, the Court imposed limitations on state regulation of civil rights and liberties.

It is appropriate that the Court emphasized the First Amendment freedoms early on in the incorporation process. The founding fathers generally believed that states, too, should not take away the freedoms in the First Amendment.

In drafting the Bill of Rights in 1789, James Madison and others had originally stated, “No state shall infringe on the equal rights of conscience, nor the freedom of speech, or of the press.” It was the only proposed amendment directly limiting states authority.

In case after case, the Court has required states to guarantee free speech, freedom of religion, fair and impartial juries, and rights against self-incrimination. Though states have incorporated nearly all rights in the document, a few rights in the Bill of Rights remain denied exclusively to the federal government but not yet denied to the states.