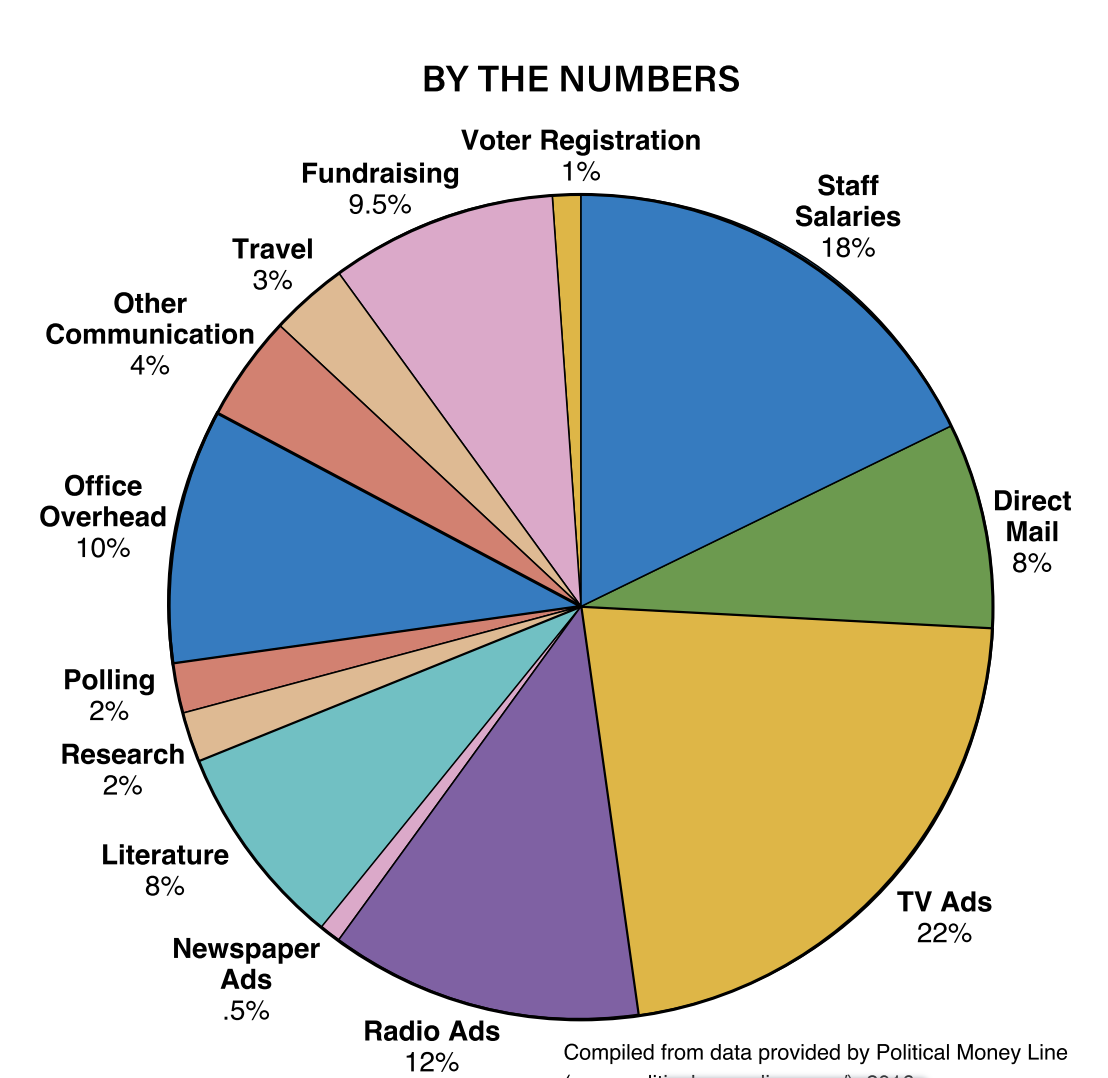

Increased Expenses:

length of election cycle

complexity

social media

advertising

Campaign Finance:

fundraising regs

donation regs

hard money

soft money

Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, 2002

Political Action Committee:

connected PAC

non-connected PAC

super PAC

Cases:

When citizens decide to run for political office, whether for county constable or president of the United States, they must consider many factors and push through a challenging path. This path includes a public examination of them, their past, their spouse, their religion, their resume, and their ideology. Candidates for office must create and manage a campaign organization of staff and volunteers to connect with the voters. They spend months traveling their districts and states campaigning. They also employ a strategy that targets certain voters, shapes their ad campaign, defines their opponent, and affects the election process. A campaign of any size requires hiring a political consultant or more staff. The average U.S. House race spends more than $1 million each cycle, and competitive Senate races in a large state can require candidates to raise and spend upwards of $30 million. Acquiring such large sums necessitates events such as fancy and expensive fundraising dinners to build strong relationships with interest groups.

Campaign Organization

Competitive candidates must work with and, at times against, their own party leaders and organizations. Outside interest groups and PACs can assist or derail a candidate’s chances to win the election. The effort to bring in money is constant and necessary to persuade voters with their message through advertising. Most candidates will assemble a team of professionals that coordinate their events, talk to the press, develop strategy, conduct voter outreach, and design television and web ads.

Candidate’s Committee

In most campaigns, from the presidential down to the county-level, a candidate will form a committee and file for candidacy with the appropriate governmental offices. In a presidential race, a leadership team that has experience in presidential politics will likely form around each candidate. In more local elections, the committee is made up of friends and family. The officially listed treasurer of the campaign has the legal responsibility to report donations, expenses, income, and receipts to the Federal Election Commission (FEC) or state authority.

Party Organizations

Alongside any candidates wearing a party label is the party itself. National, state, and local party organizations will get involved in electioneering, spend money, and mobilize members. Usually, though, when it sees a competitive primary with two or more strong candidates, the party stays out. But sometimes the party sees who the favorite is and endorses that person. Having the support of a party organization is a game changer in political campaigns, because with these relationships come a sharing of information, member email lists, donor connections, and ad costs.

More often than not, party organizations put resources toward re-electing an incumbent, because that is usually a safe bet. However, the party may choose not to endorse and instead allow voters to make that decision. The party leadership may not always be in agreement with the candidate about how to handle or manage the campaign, and intraparty friction can occur. Official or ad hoc party organizations include the local Republican Club or the state Democratic Party Committee.

Congressional Campaign Committees

Congress has four committees that primarily work to elect their members to the House and Senate. One of those committees is the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), the Democrats’ national party headquarters. Democratic House members lead this committee, but talented and hardworking staffers do the real work in campaigning and coordinating with their chosen candidates. They are the ones who will have their sleeves rolled up, circled around a table, highlighting the marginal or toss-up districts where they will spend on advertising, and the safe districts where they will not spend.

In 2017, the DCCC created a program that trained more than 14,000 new Democratic activists in less than two years. It then deployed DCCC organizers to 38 of the most vulnerable Republican-held House districts. In 2016, the DCCC provided financial backing to 28 House candidates. In 2018, that number rose to 65. As Luke Mullens has reported, the DCCC can play favorites and with intensity. “Despite the DCCC’s lip service to grassroots outreach,” says Mullens, “the party bosses back in Washington still dictate who gets on the ballot.”

Outside Groups

Both longstanding and sometimes temporary groups engage in electioneering and can have a strong effect on the election process. The most obvious examples are political action committees (PACs), such as the National Rifle Association (NRA). Standing interest groups run ads, donate to candidates, hold rallies, and impact the vote. A 527 organization is a tax-exempt group that can raise unlimited funds from individuals, corporations, and labor unions for the purpose of influencing policy or elections.

Fundraising is a critical component of any campaign, influencing both the strategy and outcomes of elections. Since the government has tracked campaign spending, cash that has flowed through federal elections has skyrocketed. Few candidates finance their own campaigns, while most rely on the party organization and thousands of individual donors for contributions. The size of a candidate’s war chest, or campaign fund, can play a significant role in determining the outcome of the election. The campaign for financial resources begins long before the campaign for votes.

Fundraising allows candidates to test their chances. Those who can gather funds begin to prove a level of support that makes them viable. In more competitive districts with strong media markets, that number will rise.

In the 2020 election, House candidates spent an average of $1.8 million, 9 percent more than in 2018. In the competitive or toss-up districts, Democrats spent an average of $9.8 million and Republicans spent an average of $8.2 million. In the 14 races where Republicans defeated Democrats, Democrats spent an average of $13.2 million and Republicans $10.5 million. Candidates in rather safe districts will often spend less than $500,000.

A grand total of $3.43 billion was spent from all sources—hard money, soft money, and PACs—in 35 Senate races. John Ossoff was the best-funded candidate with $138 million. He won with the narrowest of margins, 50.6 percent of the vote in the January 2021 runoff election.

For the 2020 presidential election, Joe Biden’s campaign raised over $1 billion. Donald Trump raised $774 million, including millions after media outlets called the election for Biden.

Senate candidates, because they are running statewide and may attract wealthier opponents, begin raising money much earlier than House candidates and devote more time to soliciting cash. Contributions by PACs to congressional candidates, who have a considerably smaller budget than presidential candidates, are essential to successful campaigns. Often, PACs will donate to an incumbent due to their likelihood of winning the election.

The internet became a campaign and fundraising tool in the 1990s. By 2002, 57 percent of all House candidates and virtually every Senate candidate used the web or email to gather funds. This type of solicitation is free, compared with an average of $3 to $4 for every direct mail request.

Campaign Strategies

How candidates develop their strategies depends on the geographic location in which they are running, their experience and background, and what issues they want to put front and center in their campaign. They usually develop a slogan, a logo, a recognizable font and color for their signs and bumper stickers, and an advertising campaign. They target particular voting blocs to build a base of support and mobilize members of their coalition to get to the voting booths.

Professional Consultants

Winning elections requires the expertise of professional consultants. These may include a campaign manager, a communications or public relations expert, a fundraiser, an advertising agent, a field organizer, a pollster, and a social media consultant. The campaign profession has blossomed as a consulting class has emerged. Staffers on Capitol Hill, political science majors, and those who have worked for partisan and nonprofit endeavors also overlap with political campaigns. Entire firms and partisan-based training organizations prepare energetic civic-minded citizens to enter this field that elects officials to implement desired policy.

One such professional is strategist Corry Bliss. In 2016, at age 35, Bliss was entrusted to run the Republicans’ Congressional Leadership Fund PAC and oversee a $100 million effort to assure Republicans get elected to the House and Senate. In the top GOP circles, Bliss is viewed as one of the party’s most influential political operatives. Bliss entered campaign work and had success in Virginia elections. Now the Leadership Fund frequently sends him from DC to a faltering campaign as a fixer.

Showcasing the Candidate

Most voters, like most shoppers, make their decision based on limited information with only a small amount of consideration. For this reason, electronic and social media, television, and focus groups are essential to winning an election. A candidate’s message often centers on common themes of decency, loyalty, and hard work.

Polling results can help candidates frame their message. Polling helps determine which words or phrases to use in speeches and advertising.

Campaigns occasionally use tracking polls to gain feedback after changing campaign strategy. They may also hold focus groups. Incumbents also rely on constituent communication over their term. Candidates also keep an eye on internet blogs, listen to radio call-in shows, and talk with party leaders and political activists to find out what the public wants. Campaigns set up registration tables at county fairs and on college campuses. They gather addresses from voter registration lists and mail out promotional pieces that highlight the candidate’s accomplishments and often include photos of the candidate alongside spouse and family. Campaigns also conduct robocalls, automated mass phone calls, to promote themselves or to denounce an opponent.

A typical campaign is divided into three segments: the biography, the issues, and the attack. Successful candidates have a unique story to tell. Campaign literature and television ads show candidates in previous public service, on playgrounds with children, on a front porch with family, or in church. These images attract a wide variety of voters. After telling the biography, a debate over the issues begins as voters shop for their candidate. Consultants and professionals believe issues-oriented campaigns motivate large numbers of people to come out and vote.

Defining the Opponent: Candidates competing for independent voters find it necessary to draw sharp contrasts between themselves and their opponents. An attack phase begins later in the race, often motivated by desperation. Underdogs sometimes resort to cheap shots and work hard to expose inconsistencies in their opponents’ voting records. Campaigns do opposition research to reveal their opponent’s missteps or any unpopular positions taken in the past. Aides and staffers comb over the Congressional Record, old interview transcripts, and newspaper articles to search for damaging quotes. They also analyze an opponent’s donor list in order to spotlight special-interest donations or out-of-state money.

Debates: As the election nears, candidates participate in formal public debates, highly structured events with strict rules governing response time and conduct. These events are risky because candidates can suffer from gaffes (verbal slips) or from poor performances. Incumbents and front-runners typically avoid debates because they have everything to lose and little to gain. Appearing on a stage with a lesser-known competitor usually helps the underdog. For races with large fields, the organizations sponsoring the debates typically determine which candidates get to participate. Their decisions are sometimes based on where candidates stand in the polls.

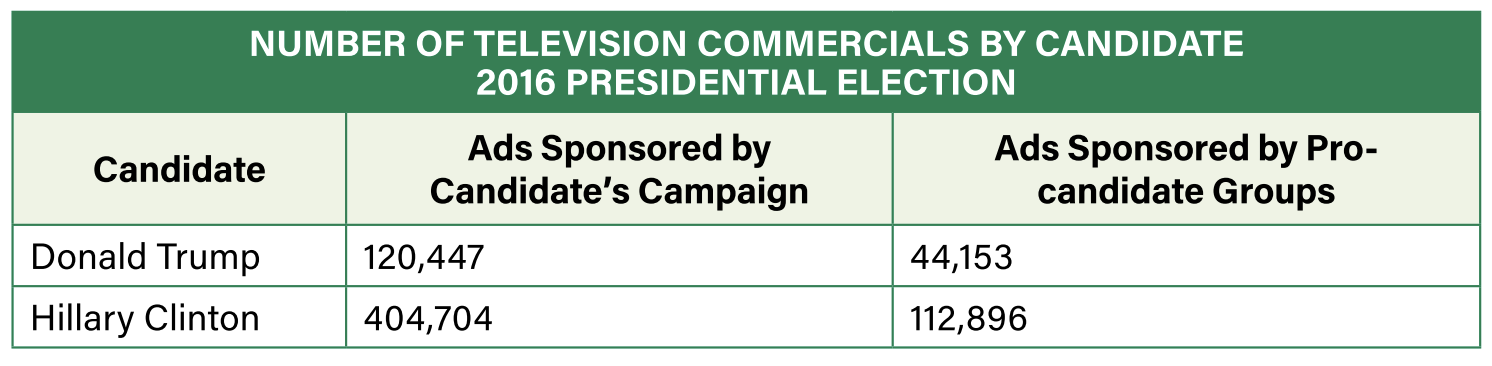

Television Appearances: The candidate’s campaign team also strategizes about appearances on television, either in news coverage or in a commercial. Veteran Democratic speechwriter and campaign consultant Bob Shrum laments, “Things are measured by when a campaign will go on television, or if they can and to what degree they can saturate the air waves.” Candidates rely on two forms of TV placement: the news story and the commercial. A news story is typically a short news segment showing the candidate in action—touring a factory, speaking to a civic club, visiting a classroom, or appearing at a political rally. Candidates send out press releases announcing their events, usually scheduled early enough in the day to make the evening news. This is free media coverage because, unlike expensive television commercials, the campaign does not have to pay for appearing in the news.

The most expensive part of nearly any campaign is television advertising. The typical modern campaign commercial includes great emphasis on imagery, action-oriented themes, emotional messages, negative characterizations of the opponent, and quick production turnaround.

Just as Kennedy became the first “television president” because he used the medium so well, Barack Obama is often called the first “social media” president. His campaign, especially for reelection in 2012, spent years on research and development to create complex programs that could link data available through social media and the party’s own paper records in a precise and highly efficient voter outreach program. Digital ad costs were also much lower than those of television ads. For about $14.5 million, Obama’s campaign bought YouTube advertising that would have cost $47 million on television.

Many supporters gave the Obama campaign permission to access their connections on social media, which were then cross-checked in the campaign’s vast data repository. Rather than asking supporters to share an Obama ad with all their connections, the campaign told supporters to do so only in key states or with a certain demographic. Since people are much more likely to trust the outreach of a friend than the outreach of a political volunteer, this strategy won many votes for Obama. Since then, parties try to develop the most efficient social media strategies to gather data for targeted outreach.

Despite the positive aspects of connectedness and free or low-cost advertisement on social media, there is a negative side. Facebook and Twitter, in particular, ran thousands of “dark ads” during the 2016 election. Dark ads are anonymously placed status updates, photos, videos, or links that appear only in the target audiences’ social media news feeds but not in the general feeds. They are created to match the personality types of their audience to the message and to manipulate people’s emotions—especially anger or fear—in order to sway their votes. Facebook and Twitter have both promised to provide more transparency to voters regarding this strategy.

Connecting to voters via social media has become essential in campaigning. For a fee, Facebook offers consultants to political groups to help reach voters, much as they offer consulting connections to a corporation to sell cereal or dog food. As Trump’s key digital campaign manager, Brad Parscale, explained on 60 Minutes, the Trump team took Facebook’s offer of help; the Clinton team did not.

The Facebook platform and technology allow campaigns to micro-target—identify by particular traits and criteria—independent voters who could be persuaded and learn what might persuade them. Perhaps an intense, issues-oriented ad would sway their opinions, or maybe the color of a button on a website might enhance the chances for a donation. Marketers use psychographics—profiles of a person’s hobbies, interests, and values—to create image-based ads that would appeal to certain personalities.

This strategy allows campaigns to tailor their messages very specifically, aiming to engage individuals based on data that predicts their behavioral responses to certain types of content. This method of targeting is not only more cost-effective than traditional media but can also be significantly more effective at influencing voter behavior because of its personalized approach.

The 2020 presidential campaign took on a classic incumbent-challenger dynamic after anti-Trump Republicans challenged Trump, and after a large field of Democrats battled for the nomination.

Primary Campaign

Four Republican candidates challenged Trump. The greatest challenge came from William Weld who won 9 percent of the vote in New Hampshire; Trump carried 84 percent. By March 18, all GOP challengers had withdrawn. They collectively won 740,536 votes and Trump received 18 million.

About 20 contenders sought the Democratic nomination, including former Vice President Joe Biden and Senators Kamala Harris, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren. In competitive Democratic primaries, candidates moved leftward. At a June 2019 Democratic presidential debate, the field was asked if their government-run health insurance plan would cover undocumented immigrants, all 10 candidates raised their hands signifying they would.

Joe Biden did finish in first, second, or third in either the Iowa caucuses or the New Hampshire primary, but he won South Carolina. Biden officially clinched the nomination when he swept seven states holding primaries on June 2. He received 19 million votes, Sanders 9.6 million, and the others split the remaining 8 million votes.

The General Election

President Trump had an uphill battle to win re-election, considering he never enjoyed a job approval rating of more than 50 percent and the economy was shaken by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Republicans emphasized the immigration problem and pushed to give Trump another term to fix it. They pointed to liberal policies as the cause of the racial unrest, protests, and riots. “Socialism!” was a common cry from the right in trying to paint liberal Democratic positions. Conversely, the Democrats’ strategy involved exposing Trump’s record, his reputation on the world stage, his handling of COVID-19, and his conflicts of interest. Quite simply, the Biden campaign suggested a return to predictability.

The first presidential debate on September 29 was ugly. CBS News counted that Trump interrupted Biden a total of 73 times. Biden eventually called Trump a “clown,” and asked angrily, “Will you shut up man?” Nielsen Research estimated that 73.1 million viewers watched. In a Five Thirty Eight poll, viewers thought Biden beat Trump nearly 60 percent to 33 percent. Roughly 63 million people tuned in to watch a final, somewhat tame debate in Nashville. A CNN poll shows 53 percent of viewers thought Biden won; 39 percent said Trump won.

COVID-19 changed campaign and election norms and administration. According to a U.S. Census Bureau report, 69 percent of voters nationwide cast a ballot in a non-traditional way (not at the polls on election day). That was an increase from about 40 percent in 2016.

As with recent presidential elections, the bulk of the effort, money, and time was spent in the battleground states. Once all the votes were counted, Biden won 81,282,916 popular votes to Trump’s 74,223,369, as compiled by The Cook Political Report. This gave Biden 306 electoral votes and Trump 232. In 2020, Democrats flipped the swing states of Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Biden’s Victory

According to a Pew Research Center study, the key shifts occurred among suburban voters and independents. “On balance, these shifts helped Biden a little more than they helped Trump,” the report concludes. Additionally, two-thirds of those voting for a minor party in 2016, about 6 percent of the electorate, came over to Biden or Trump in 2020. Of those voters, 53 percent voted for Biden and 36 percent voted for Trump.

Trump refused to concede. His legal team and Republicans on his behalf filed 73 total cases across the United States, challenging election outcomes for a host of reasons. As a Stanford-M.I.T Healthy Elections Project sums up well, “The evidence they proffered failed to make headway with judges of all stripes” while they succeeded in sowing mistrust in U.S. elections.

January 6

After weeks of publicly declaring he’d been robbed of the election, Trump promoted a rally in Washington, DC, on January 6—the same day a joint session of Congress ceremonially counts the electoral votes. Trump gave a speech and whipped his supporters into a frenzy. They then stormed the Capitol Building overtaking police and security. They penetrated the Senate chamber and Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office, and chanted “hang (Vice President) Mike Pence.” Days later, the House of Representatives impeached Trump in a vote of 232 to 197 (10 Republicans voted to impeach). Joe Biden was sworn in on January 20 without incident and without Trump present. The Senate trial followed, and on February 13, the Senate voted 57 to 43 to convict for “incitement of insurrection,” but failed to reach the two-thirds requirement.

Campaign Finance

Winning an election requires a political campaign to first make voters aware of a candidate and then to persuade the same voters that he or she is the best choice. That takes money. Mark Hanna, politico and campaign manager for President William McKinley, certainly knew this as well, whether he publicly made the above statement or not. Candidates today require everything from bumper stickers and yard signs to a full-time staff and televised commercials.

Campaign Finance

The quote from Mark Hanna illustrates that politicians realize money is at the heart of politics. The entanglement of money and politics reached new levels when people with unscrupulous business practices became fixtures in the political process in the late 19th century in an effort to influence and reduce the federal government’s regulation of commerce. The bulk of today’s relevant campaign finance regulations, however, came about much later—in the early 1970s—and other laws and Supreme Court decisions followed.

Federal Legislation on Campaign Finance

In 1971, Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which tightened reporting requirements and limited candidates’ expenditures. Despite this law, spending in the 1972 presidential race between Richard Nixon and George McGovern reached $91 million. The public soon realized how much money was going through the campaign process and how donors had subverted the groundbreaking yet incomplete 1971 act. Congress responded with the 1974 amendment to the FECA.

The Federal Election Commission

The 1974 law prevented individual donors from giving more than $1,000 to any federal candidate and prevented political action committees from donating more than $5,000 in each election (primaries and general elections are each considered “elections”). It capped the total a candidate could donate to his or her campaign and set a maximum on how much the campaign could spend.

The law created the Federal Election Commission (FEC) to monitor and enforce the regulations. It also created a legal definition for political action committees (PAC) to make donations to campaigns, declaring that they must have at least 50 members, donate to at least five candidates, and register with the FEC at least six months in advance of the election.

The FEC has structural traits to help it carry out several responsibilities. The president appoints the FEC’s board of commissioners to oversee election law, and the Senate approves them. This commission always has an equal number of Democrats and Republicans. The FEC requires candidates to register, or file for candidacy, and to report campaign donations and expenses on a quarterly basis. A candidate’s entire balance sheet is available to the government and the public. The site www.fec.gov has a database that allows anyone to see which individuals or PACs contributed to the candidates and in what amounts.

One of the first challenges to FEC law came with the case of Buckley v. Valeo. In January 1975, a group of conservatives and liberals joined New York Senator James Buckley to overturn the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) in the courts. They argued that the early 1970s law unconstitutionally limited free speech. The Court upheld the law’s $1,000 limit on individual donations and the $5,000 limit on political action committee (PAC) donations, claiming such limits did not violate free speech guarantees. However, the Court also ruled that Congress cannot limit a candidate’s donation to his or her own campaign nor can it place a maximum on the overall receipts or expenditures for a federal campaign. With the Buckley ruling, Congress and the Court ultimately reached consensus that unlimited donations make for unfair elections.

Even after the ruling in Buckley, however, television advertising and money became more important in campaigns as interest groups, politicians, and lawyers found loopholes in the law. The FECA covered only money going directly to and from a candidate’s treasury. If a non-candidate wanted to spend money to influence an election—for example, to buy a radio ad for or against a candidate—there were no limits. Hard money, a donation given directly to a candidate, could be traced and regulated. But soft money, a donation to a party or interest group, was not tracked. Therefore, the party could flood a congressional district with television ads that paint the opponent in a bad light, causing large, ultimately untraceable spending on electioneering at the end of a campaign. Unsurprisingly, soft money spending escalated.

This situation brought greater attention to soft money’s influence on elections and highlighted how much that influence was able to subvert the spirit of the 1970s reforms. Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Russ Feingold (D-WI) had pushed for greater campaign finance regulations since the mid-1990s. After some modification, the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) of 2002, also known as the McCain-Feingold Act, finally passed the House with a 240-189 vote and the Senate with a 60-40 vote, and President Bush signed it. The act banned soft money contributions to the national parties, increased the limits on hard money donations to $2,000 from individuals (with future adjustments for inflation), $5,000 from PACs, and $25,000 from the national parties per election cycle. The law also placed an aggregate limit on how much an individual could donate to multiple candidates in a two-year cycle. Since then, the limit has been raised to $2,700 per individual.

The BCRA prohibited PACs from paying for electioneering communications on radio or TV using campaign treasury money within 60 days of the general election and 30 days of a primary. To clear up who or what organization is behind a broadcasted advertisement, the McCain-Feingold law also requires candidates to explicitly state, “I’m [candidate’s name] and I approve this message.” That statement must last at least four seconds.

Though the law was dubbed bipartisan, the vote in Congress and the reaction to the law has been somewhat partisan, with more Democratic support than Republican. It was challenged immediately by then-Senate Majority Whip, Mitch McConnell (R-KY), in the courts and largely upheld. The 2010 case of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (FEC), however, overturned key parts of the law.

Debates over free speech and competitive and fair elections have intensified since the Citizens United ruling. Free speech advocates, libertarians, and many Republicans view most campaign finance regulations as infringements on their freedoms, so they hailed the ruling. Others agreed with President Obama when he criticized the ruling at his 2010 State of the Union address as a decision that would “open the floodgates to special interests.”

In addition to allowing ads by outside or soft money groups immediately before an election, the Court’s ruling also allowed for unlimited contributions to these groups from individual citizens and other organizations. This dark money has penetrated political campaigning, causing a lack of transparency about where the money originates. Even though political ads must express who is behind them, determining exactly where the money ultimately comes from is hard to do.

“Citizens United changed the culture at the same time that it changed the law,” according to Zephyr Teachout, Fordham University law professor and author of “Corruption in America.” “Before Citizens United, corporate or individual money could be spent with a good enough lawyer. But after Citizens United v. FEC, unlimited corporate money spent with intent to influence was named, by the U.S. Supreme Court, indispensable to the American political conversation.”

The ruling also concentrates who dominates the political discussion. Five years after the ruling, the Brennan Center at New York University found that of the $1 billion spent, about 60 percent of the donations to PACs came from 195 people or couples. More recently, an analysis by OpenSecrets.org found that during the 2016 election cycle, the top 20 individual donors gave more than $500 million to PACs. The 20 largest organizational donors also gave a total of more than $500 million to PACs. And more than $1 billion came from the top 40 donors. About one-fifth of political donations spent in all federal elections in 2016 came from dark money sources.

In the 2016 election cycle, special interests spent at least $183.5 million in dark money, up from $5.2 million in 2006. Of that, liberal special interests spent at least $41.3 million, or 22.5 percent; conservatives spent most of the remaining amount.

Though Democrats are more prone to use Citizens United as a rallying cry against corporate special interests, they have also benefited from the ruling. As Sarah Kleiner of the Center for Public Integrity pointed out, “many Democrats have taken full advantage of the fundraising freedoms Citizens United has granted them.” Candidate Hillary Clinton, especially, “benefited from a small army of super PACs and millions of dollars in secret political money.” More specifically, in the 2016 election, the Clinton presidential campaign received 18 percent of its contributions, about $220 million, from such sources, whereas Trump received 12 percent of his overall contributions, or roughly $80 million, from PACs.

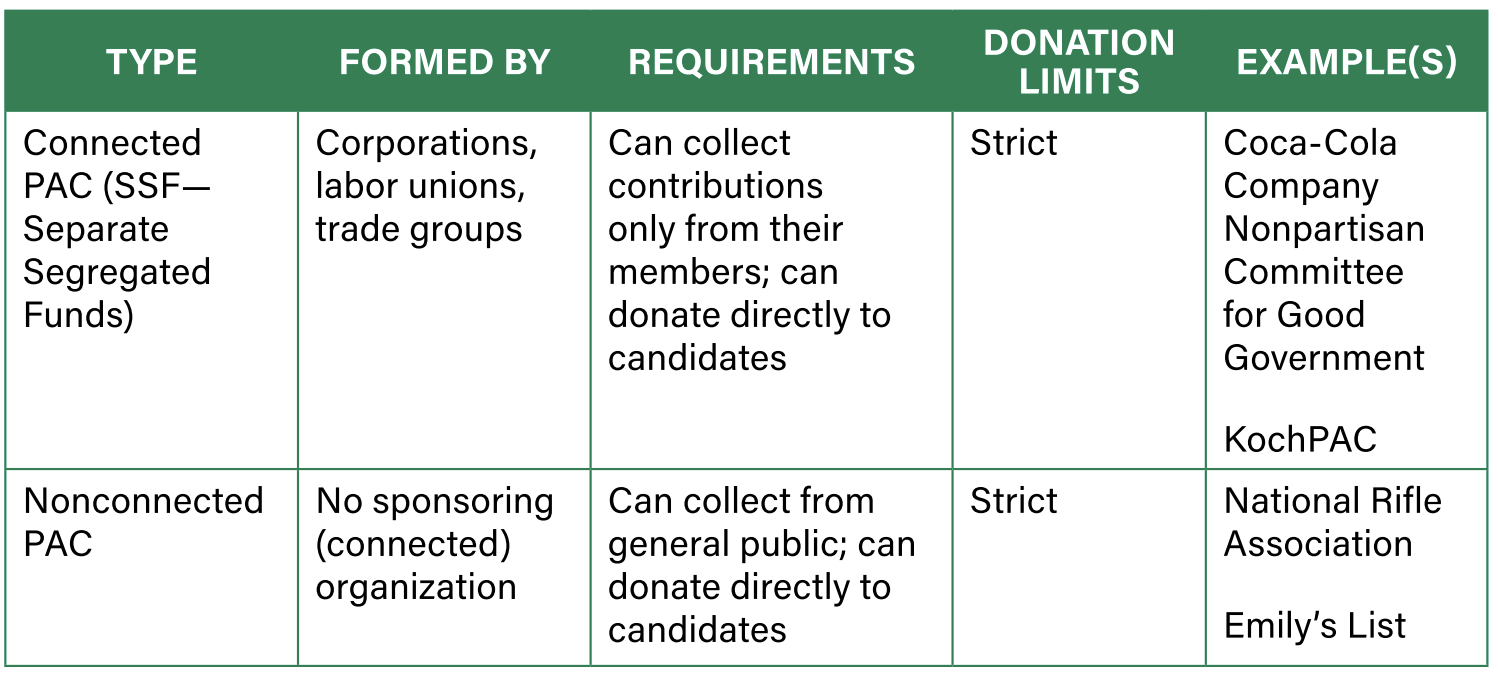

Types of PACs

Campaign finance laws define several different types of political action committees, distinguished by how they are formed, how they are funded, and how they can disperse their funds. Some also have different limits on the donation amount from individuals per year or election.

Connected PACs

Corporations, labor unions, and trade organizations are not allowed to use money from their treasuries to influence elections. However, they are allowed to form connected PACs-political action committees funded separately from the organization’s treasury through donations from members-and make limited campaign contributions in that way. Connected PACs are also known as Separate Segregated Funds (SSF) because of the way the money is separated from the sponsoring organizations’ treasuries. They cannot solicit donations from anyone who is not a member of the organization.

Nonconnected PACs

These political action committees have no sponsoring organization and often form around a single issue. They can solicit funds from anyone in the general public, and they can make direct donations to candidates up to limits set by law. Like the connected PACs, nonconnected PACs must register with the FEC and disclose their donors.

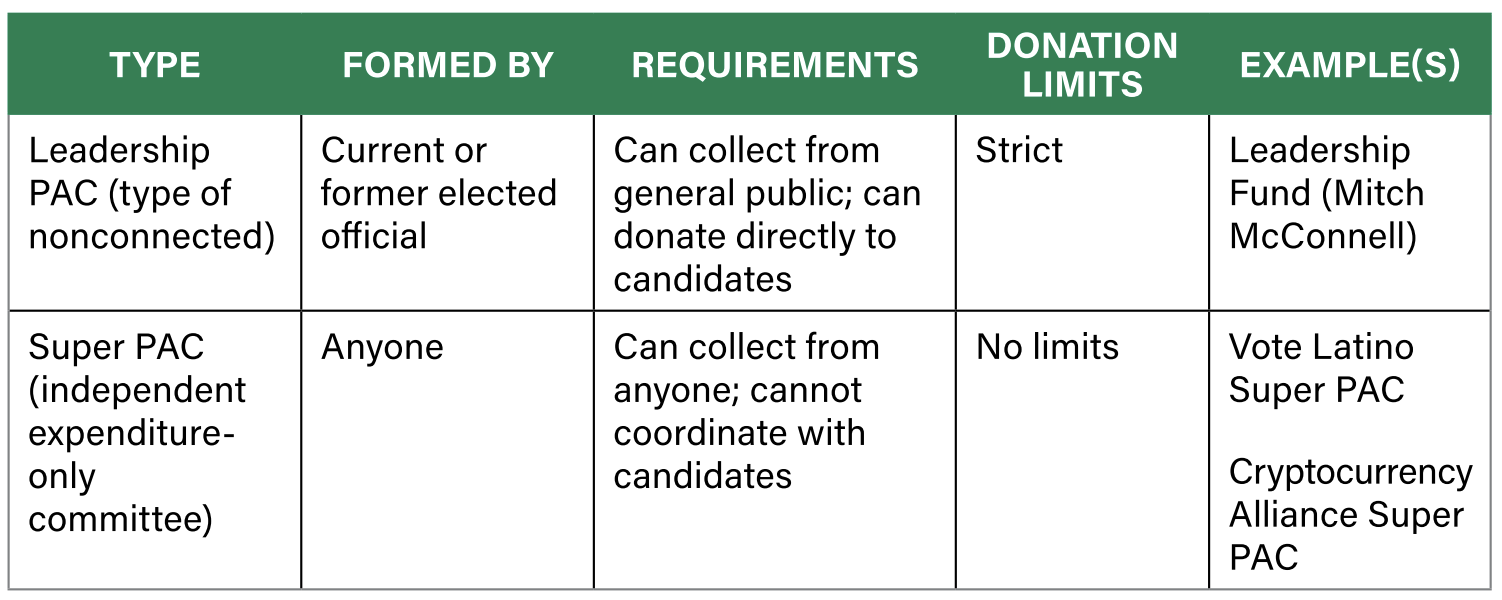

Leadership PACs

Leadership PACs are a type of nonconnected PAC. They can be started by any current or former elected official and can raise money from the general public. Though the money cannot be used to fund the officials own campaigns, funds in a leadership PAC can be used to cover travel and other expenses for other candidates.

Super PACs

These are the newest kind of political action committee, whose creation resulted from the Supreme Court ruling in Citizens United v. FEC and the U.S. District Court ruling in Speechnow v. FEC, both cases decided in 2010. The Citizens United ruling opened the door for unlimited donations to and spending by large PACs, as long as the don’t formally coordinate or communicate with the candidate’s campaign. The Speechnow ruling determined that those contributions to Super PACs should have no limit placed on them.

Four years after Citizens United, the court addressed campaign finance again in McCutcheon v. FEC (2014). McCutcheon, a generous donor to candidates across the nation, questioned multiple points of law, especially the FEC’s aggregate limit of donations. While upholding the maximum contributions for individual candidates or committees, the ruling in McCutcheon removed the limit imposed by BCRA on how much an individual could donate to multiple candidates in a two-year cycle. This change greatly increased the popularity of the joint fundraising committee (JFC)—a coordinated fundraising effort of a number of candidates and committees. Rich donors can now write just one large check (more than $1 million depending on how many candidates and committees are in the JFC). The contributions are then shared among the members of the JFC according to their own agreement.

These changes affected political parties in several ways. First, state party committees are often members of JFCs, so they received a share of the contributions. Once the money was in their coffers, there was no law against returning a sizable amount of it to the national committees. Through this process, the political parties worked around their limits on hard money and once again had more control of campaign donations and thereby influence on candidate choice and election results. Second, the unofficial structure of the party has changed from a top-down vertical organization to more of a horizontal network. Although the joint fundraising committees and Super PACs are not officially part of the party, they are key players in campaigns, so the political party has become part of a web of actors, dependent on elements outside of the party for funds.