Need to Know:

jurisdiction

original

appellate

Judiciary Act of 1789

court of appeals

district court

judicial review

Federalist No. 78:

What was Hamilton’s argument for the powers of the judiciary, and his response to the concern about the power & lifetime appointment

Cases:

The courts handle everything from speeding tickets to death penalty cases. State courts handle most disputes, whether criminal or civil. Federal courts handle crimes against the United States, high-dollar lawsuits involving citizens of different states, and constitutional questions. Federal courts are designed to protect the judiciary’s independence. The U.S. Supreme Court is the nation’s highest tribunal, which, through judicial review and its rulings, shapes the law and how it is carried out.

Constitutional Authority of the Federal Courts

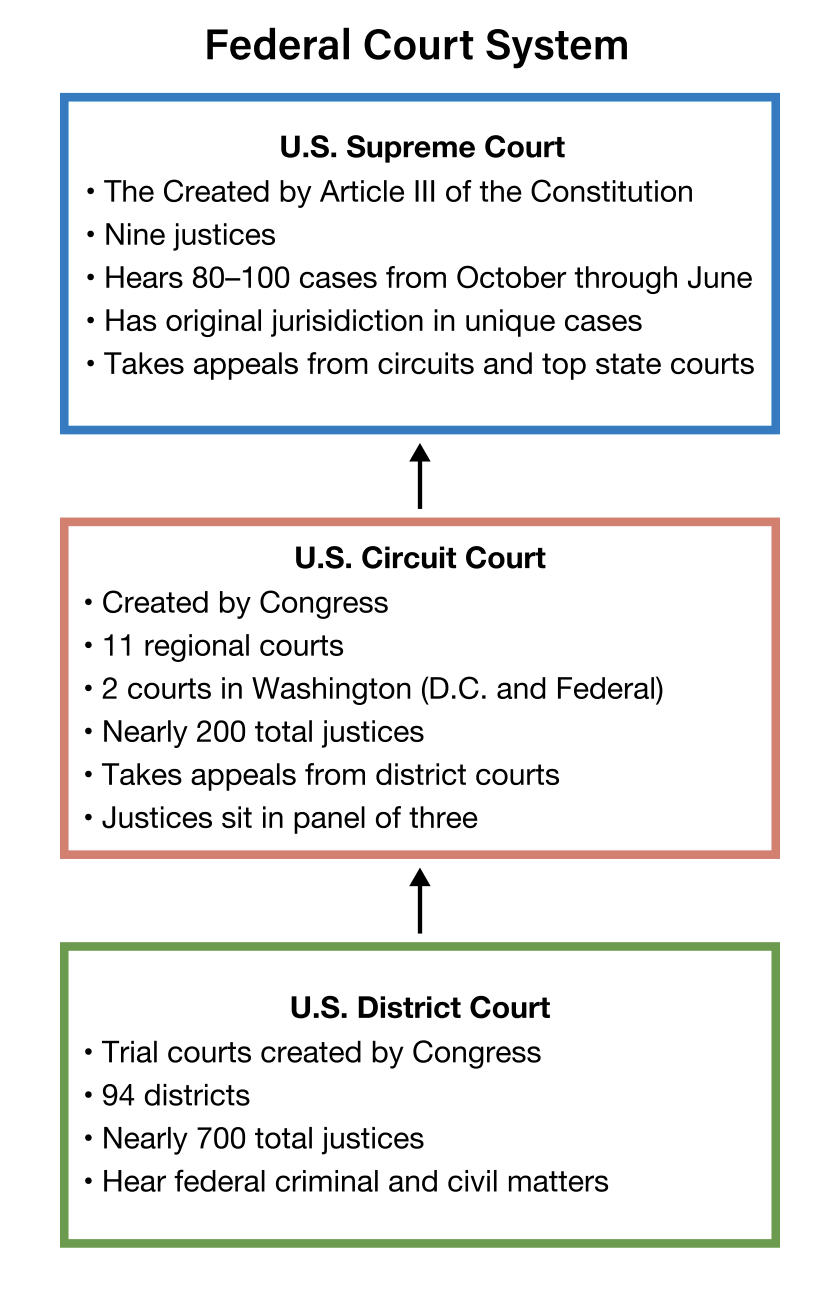

Today’s three-level federal court system consists of the U.S. District Courts on the lowest tier, the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals on the middle tier, and the U.S. Supreme Court alone on the top. These three types of courts are known as “constitutional courts” because they are either directly or indirectly mentioned in the Constitution. All judges serving in these courts are appointed by presidents and confirmed by the Senate to hold life terms.

Article III

The only court directly mentioned in the Constitution is the Supreme Court, though Article III empowered Congress to create “inferior” courts. Article III established the terms for judges, the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, the definition of treason, and a defendant’s right to a jury trial.

Judge’s Terms

All federal judges “shall hold their offices during good behavior,” the Constitution states. Although this term of office is now generally called a “life term,” most U.S. judges retire or go on senior status at age 65, and a handful have been impeached and removed. This key provision empowers federal judges to make unpopular but necessary decisions. The life term assures that judges can operate independently from the other branches, since the executive and legislative branches have no power to remove justices over disagreements in ideology. The life term also allows for consistency over time in interpreting the law. Congress cannot diminish judges’ salaries during their terms in office. This way, Congress cannot use its power of the purse to leverage power against this independent branch.

Jurisdiction

The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction – the authority to hear a case for the first time – in cases affecting ambassadors and public ministers and those in which a state is a party. For the most part, however, the Supreme Court acts as an appeals court with appellate jurisdiction.

A Three-Level System

The first Congress essentially defined the three-tier federal court system with the Judiciary Act of 1789. Originally, one district court existed in each state. The law also defined the size of the Supreme Court with six justices, or judges. President Washington then appointed judges to fill these judgeships. In addition to the district courts, Congress created three regional circuit courts designated to take cases on appeal from the district courts. Supreme Court justices were assigned to oversee the U.S. appeals courts that include clusters of states, a “circuit,” and presided over periodic sessions. The justices would hold one court after another in a circular path, an act that became known as “riding circuit.”

U.S. District Courts

There are 94 district courts in the United States – at least one in each state, and for many less-populated western states, the district lines are the same as the state lines. Districts may contain several U.S. courthouses served by several federal district judges. Nearly 700 district judges preside over trials concerning federal crimes, lawsuits, and disputes over constitutional issues. Annually, the district courts receive close to 300,000 case filings, most of a civil nature.

A Trial Court

U.S. district courts are trial courts with original jurisdiction over federal cases. The litigants in a trial court are the plaintiff – the party initiating the action – and the defendant, the party answering the claim.

In a criminal trial, the government is the plaintiff, usually referred to as the “prosecution.” In civil trials, a citizen-plaintiff brings a lawsuit against another, the defendant, who allegedly injured the plaintiff. “Injury” could be physical injury – as one motorist may have recklessly caused to another – but more often it is a financial injury, alleging the defendant’s fault, measured in dollars.

At times, it is an accusation that the government has injured a citizen, or a company, by violating their liberty.

Federal Crimes

The U.S. district courts try federal crimes, such as counterfeiting, mail fraud, or evading federal income taxes – crimes that violate the enumerated powers in the Constitution, Article I, Section 8. Most violent crimes, and indeed most crimes overall, are tried in state courts. However, Congress has outlawed some violent crime and interstate actions, such as drug trafficking, bank robbery, terrorism, and acts of violence on federal property.

For example, in United States v. Timothy McVeigh (1998), the government argued that McVeigh was responsible for an explosion in an Oklahoma City federal building that killed 168 people. A federal court found him guilty and sentenced him to death.

U.S. Attorneys

Each of the 94 districts has a U.S. attorney, appointed by the president and approved by the Senate, who represents the federal government in federal courts. These executive branch prosecutors work in the Department of Justice under the attorney general, assisted by the FBI and other federal law enforcement agencies. Nationally, they try nearly 80,000 federal crimes per year. Of those, immigration crimes and drug offenses take up much of the courts’ criminal docket. Fraud is third.

Civil Cases

Citizens can also bring civil disputes to U.S. court to settle a business or personal conflict. Some plaintiffs sue over torts, or civil wrongs that have damaged them. In a lawsuit, the plaintiff files a complaint, a brief explaining the damages and why the defendant should be held liable. The plaintiff must prove the defendant’s liability or negligence with a “preponderance of evidence” for the court to award damages. Most civil disputes, even million-dollar lawsuits, are handled in state courts.

Disputes involving constitutional questions also land in this court. In these cases, a federal judge, not a jury, determines the outcome because these cases involve a deeper interpretation of the law. Sometimes a large group of plaintiffs accuse the same party caused damage to them and will file a class action suit.

After a decision, courts may issue an injunction, or court order, to the losing party in a civil suit, making them act or refrain from acting to redress a wrong.

Suing the Government

Sometimes a citizen or group sues the government. Technically, the United States operates under the doctrine of sovereign immunity – the government is protected from suit unless it permits such a claim. Over the years, Congress has made so many exceptions that it even established the U.S. Court of Claims to allow citizens to bring complaints against the United States. Individual citizens and groups also regularly bring constitutional arguments before the courts. One can sue government officials acting in a personal capacity. For example, the secretary of defense could be personally sued for causing a traffic accident that caused thousands of dollars in damage to another’s car. But the secretary of defense or Congress cannot be sued for the loss of a loved one in a government-sanctioned military battle.

U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals

Above the district courts are the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals. In 1891, with U.S. expansion and the increased caseload for the traveling Supreme Court justices riding circuit, Congress made the U.S. appeals courts permanent, full-time bodies. Appeals courts don’t determine facts; instead, they shape the law.

The losing party from a fact-based trial can appeal based on the concept of certiorari, Latin for “to make more certain.” The appellant must offer some violation of established law, procedure, or precedent that led to the incorrect verdict in a trial court. Appeals courts look and operate differently than trial courts. Appeals courts have a panel of judges sitting at the bench but no witness stand and no jury box because such courts do not entertain new facts, but rather a narrow question or point of law.

The petitioner appeals the case, and the respondent defends the lower court’s ruling. The public hearing lasts about an hour as each side makes oral arguments before the judges. Appeals courts don’t declare guilt or innocence when dealing with criminal matters, and they don’t generally reverse judgments in civil suits. They rule on procedural matters in which the lower courts or other parts of government may have erred, not followed precedent, or violated the Constitution. They periodically establish new principles with case law. After years of deciding legal principles, appeals courts have shaped the body of U.S. law.

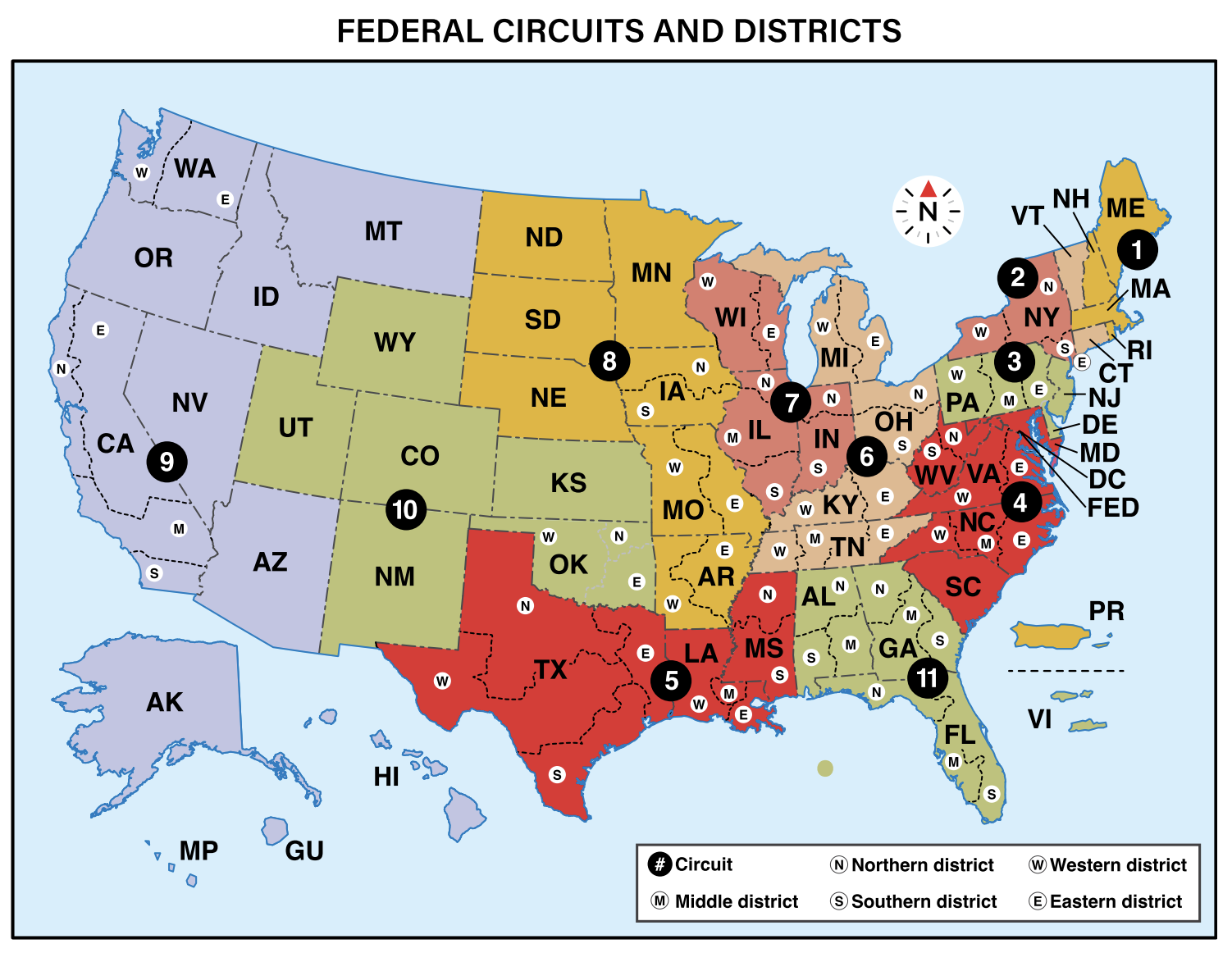

The U.S. Courts of Appeals consist of 11 geographic circuits across the country. Appeals court rulings stand within their geographic circuits.

In addition to the 11 circuits, two other appeals courts are worthy of note.

The Circuit Court for the Federal Circuit hears appeals dealing with patents, contracts, and financial claims against the United States. The Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, among other responsibilities, handles appeals from those fined or punished by executive branch regulatory agencies.

The DC Circuit might be the second most important court in the nation and has become a feeder for Supreme Court justices.

The United States Supreme Court

Atop this hierarchy is the U.S. Supreme Court, with the chief justice and eight associate justices. The Supreme Court mostly hears cases on appeal from the circuit courts and from the state supreme courts. The nine members determine which appeals to accept, sit en banc (French for “on the bench,” where all judges sit for the case) for attorneys’ oral arguments, pose questions, and engage in a discussion with the litigants. They will consider their decision for weeks, sometimes months, vote whether or not to overturn the lower court’s ruling, and issue their reasoning. The Court overturns about 70 percent of the cases it takes. Once the Supreme Court makes a ruling, it becomes the law of the land. Contrary to what many believe, the Supreme Court doesn’t hear trials of serial murders or billion-dollar lawsuits. However, it decides on technicalities of constitutional law that have a national and sometimes historic impact. This power of judicial review, to check the other branches, was first exercised by the Supreme Court in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison.

Common Law and Precedent

Courts follow a judicial tradition begun centuries ago in England. Common law refers to the body of court decisions that make up part of the law. Court rulings often establish a precedent – a ruling that firmly establishes a legal principle. These precedents are generally followed later as subordinate courts must and other courts will consider following. The concept of stare decisis, or “let the decision stand,” governs common law.

Lower courts must follow higher court rulings. Following precedent establishes continuity and consistency in law. Therefore, when a U.S. district court receives a case that parallels an already decided case from the circuit level, the district court is obliged to rule the same way, a practice called binding precedent. Even an independent-minded judge who disagrees with the higher court’s precedent knows an appeal of a uniquely different decision, based in similar circumstances, will likely be overruled by the court above. That’s why all courts in the land are bound by U.S. Supreme Court decisions.

Judges also rely on persuasive precedent. That is, they can consider past decisions made in other district courts or far-away circuit courts as a guiding basis for a decision. Precedents can, of course, be overturned. No two cases are absolutely identical, which is precisely why judges make decisions on a case-by-case basis. Also, attitudes and interpretations differ and evolve over time in different courts.

How Cases Reach the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is guided by Article III, congressional acts, and its own rules. Congress is the authority on the Court’s size and funding. The Court began creating rules in 1790 and now has 48 formal rules, as well as less formal customs and traditions that guide the Court’s operation. The Court has both original and appellate jurisdiction. Only in rare situations does the Supreme Court exercise original jurisdiction and thus serve as a trial court, typically when one state sues another over a border dispute or to settle some type of interstate compact.

As the nation’s highest appeals court, the Supreme Court takes cases from the 13 U.S. circuits and the 50 states. Two-thirds of appeals come through the federal system, directly from the U.S. circuit courts, because the Supreme Court has a more direct jurisdiction over cases originating in federal district courts than in state trial courts.

Like the circuit courts, the Supreme Court accepts appeals each year from among thousands filed. The petitioner files a petition for certiorari, a brief arguing why the lower court erred. The Supreme Court reviews this to determine if the claim is worthy and if it should grant the appeal. If an appeal is deemed worthy, the justices add the claim to their “discuss list.” They consider past precedents and the real impact on the petitioner and respondent. The Supreme Court does not consider hypothetical or theoretical damages; the claimant must show actual damage. Finally, the justices consider the wider national and societal impact if they take and rule on the case. Once four of the nine justices agree to accept the case, the appeal is granted. This rule of four, a standard less than a majority, reflects courts’ commitments to claims by minorities.

Opinions and Caseload

Chief Justice John Marshall’s legacy of unanimity has vanished. The Court comes to a unanimous decision only about 30 to 40 percent of the time. Therefore, it issues varying opinions on the law. Once the Court comes to a majority, the chief justice, or the most senior justice in the majority, either writes the Court’s opinion or assigns it to another justice in the majority. Typically, those justices who write the majority opinion, reflecting the Court’s ruling, have expertise on the topic or are obviously passionate about the issue. Like a statute for Congress or an executive order for the president, a court ruling is the judicial branch’s contribution to the nation’s law. The majority opinion sums up the case, the Court’s decision, and its rationale.

Justices who differ from the majority can draft and issue differing opinions. Some may agree with the majority and join that vote but have reservations about the majority’s legal reasoning. They might write a concurring opinion. Those who vote against the majority often write a dissenting opinion. A dissenting opinion has no force of law and no immediate legal bearing but allows a justice to explain his or her disagreements to send a message to the legal community or to influence later cases. On occasion, the Court will issue a decision without the full explanation, known as a per curiam opinion.