Ideology & Policy Examples:

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act, 1996; Dream Act, English as an official language debate, multiculturalism vs assimilation debate.

Economic Policy Debate:

conservatives, liberals, libertarians, Keynesian Economics, Supply-Side Economics

Social Issues& Policy:

conservatives

liberals

libertarians

Social Issue Ideological Reactions to:

Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992)

Widely held political ideologies shape policy debates and choices, including the government’s domestic, economic, and foreign policies. Policy is created and shaped by the federal government, even in small ways, such as when a member of Congress inserts language into a bill, when the president discusses relations with another head of state, when the U.S. Postal Service changes its delivery schedule, or when a court sets a precedent. The impetus for those policies, however, stems from Americans’ values, attitudes, and beliefs. These drive the formation, goals, and implementation of public policy over time.

Influences on Public Policy

Americans have a range of values, attitudes, and beliefs. These influence the development, goals, and implementation of public policy over time. Policies in place at any given time represent the success of the parties whose ideologies they represent and the political attitudes and beliefs of citizens who choose to participate in politics. Following are some of the key theories or pathways to policy. These differing pathways reflect some of the different types of democracy you read about in Topic 1.2, since the United States has elements of each of them.

Majoritarian Policy Making

Democratic government, a foundational principle in America, is meant to represent the people’s views through elected representatives. This principle is reflected through majoritarian policy making, which emerges from the interaction of people with government in order to put into place and carry out the will of the majority. Popular ideas will work their way into the body politic via state and national legislatures. A president seeking a second term may go with public opinion when there is an outcry for a new law or a different way of enforcing an existing law. State referenda and initiatives, too, are a common way for large grassroots efforts to alter current policy when state assemblies refuse to make laws that reflect the public will. These are examples of participatory democracy.

This democratic system sounds fair and patriotic. But the framers also put into place a republic of states and a system to ensure that the tyranny of the majority did not run roughshod over the rights of the minority. Additionally, the framers warned, factions -often minority interests-will press government to address their needs, and at times government will comply.

Interest Group Policy Making

Interest groups have a strong influence and interact with all three branches in the policy making process. They fund candidates who support their agendas, experts sympathetic to their concerns provide testimony at hearings, and they push for specific areas of policy to satisfy their members and their philosophy.

Interest groups represent a pluralist approach to policymaking. The interests of the diverse population of the United States, ethnically and ideologically, compete to create public policy that addresses as many group concerns as compromise allows.

Balancing Liberty and Order

No matter the approach to public policymaking, two underlying principles guide debate. One is the core belief in individual liberties. The other is the shared belief that one important role of government is to promote stability and social order. Policy debates are often an effort to find the right balance between these fundamental values.

Governmental laws and policies balancing order and liberty are based on the Constitution and have been interpreted differently over time.

Ideology and Economic Policy

The philosophy of the president and the collective attitude of Congress can drastically impact the federal budget, taxes paid into the federal purse, the value of the dollar, and trade relationships with foreign nations. Except for partisan identification, there are no greater determiners on Election Day than a voter’s view of the economy and the economic scorecard for politicians in power.

Incumbent presidents who sought reelection during a bad economy invariably lost their bid for a second term. The classic example is Herbert Hoover, who in 1932 sought reelection during the worst economy in history and suffered a landslide loss to Franklin Roosevelt. Presidents Ford in 1976, Carter in 1980, and Bush Sr. in 1992 all lost their quests for a second term during poor economic times. In 1992, with the Cold War over and the economy in bad shape, Bill Clinton’s campaign manager, James Carville, reminded his candidate, “It’s the economy, stupid.” People who are adversely affected by the economy will vote against members of the incumbent party.

Political Ideologies and the Marketplace

Governing economic and budgetary issues is challenging, especially considering the general desires of the citizenry. Most people have three desires for government finances: lower taxes, no national debt, and enhanced government services. Having all three is impossible. So how do politicians satisfy these wants? “Don’t tax me, don’t tax thee, tax that fellow behind the tree,” Senator Russell Long (D-LA) allegedly said. Long came from a family of adept Louisiana politicians who knew that the answer was to raise taxes on “other people.” For example, governments create excise taxes on particular products or services, such as cigarettes or gambling (often called “sin taxes”), hitting only a few people, many of whom won’t stop making such purchases even when taxes lead to higher prices.

A key difference between political ideologies is a set of beliefs about the extent to which the government should be involved in the economy. Liberal ideologies favor considerable government involvement in the economy as a way to keep it healthy and protect the public good. For example, during the economic decline of the Great Recession (2007-2013), President Obama and Democrats in power supported a high level of government spending to stimulate the economy with the Recovery Act of 2009. The law received practically no Republican support in Congress. Republicans criticized the bill for its emphasis on government spending rather than tax cuts, which is what the previous president, George W. Bush, had supported in the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008. Republicans argued the tax cuts put more money into the hands of citizens, giving them more control over how to spend it. Libertarian opposition was even stronger, since libertarians saw the law as an inappropriate expansion of government power.

Varying views on the role of government involvement and regulation of the economy are based on different economic theories. Liberals subscribe to the theory of English economist John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946) to support their views. Conservatives rely on “supply-side” theories developed by economists during the presidency of Republican Ronald Reagan (1981-1989). Libertarians have been influenced by economists such as Alan Greenspan, who was Chairman of the Board of the Federal Reserve System from 1987-2006, and Milton Friedman, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976.

Keynesian Economics

Keynesian economics addresses fiscal policy, that part of economic policy that is concerned with government spending and taxation. Keynes offered a theory regarding the aggregate demand (the grand total spent by people) in an economy. He theorized that if left to its own devices, the market will not necessarily operate at full capacity. Not all persons will be employed, and the value of the dollar may drop. Much depends on how much people spend or save. Saving is wise for individuals, but when too many people save too much, companies will manufacture fewer products and unemployment will rise. When people spend too much, conversely, their spending will cause a sustained increase in prices and shortages of goods.

Keynes believed that the government should create the right level of demand. When demand is too low, the government should put more money into the economy by reducing taxes and/or increasing government spending, even if doing so requires borrowing money. This approach led to the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. If demand is too high, the government should take money out of the economy by taxing more (taking wealth out of citizens’ pockets) and/or spending less.

Keynesian economics also recognizes a multiplier effect, a mechanism by which an increase in spending results in an economic growth greater than the amount of spending. That is, output increases by a multiple of the original change in spending that caused it. For example, with a multiplier of 1.5, a $10 billion increase in government spending could cause the total output of goods and services to rise by $15 billion. In concrete terms, consider what happens if the government begins public construction projects. Not only are unemployed construction contractors put to work, but bricklayers, electricians, and plumbers are too. With an income once again, these workers can afford to buy products and services from other retail businesses, whose income and demand for more employees increases.

Keynesian economics represents one end of the spectrum on the role of government regulation of the marketplace, calling for significant government involvement. Liberal ideologies tend to favor this level of government involvement. Democrat Franklin Roosevelt based his New Deal concept largely on the Keynesian model. The federal government built an array of public works during the Great Depression (1929-1939). Agencies such as the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Public Works Administration (PWA), and the Civilian Conservation Corp (CCC) built new schools, dams, roads, libraries, and other capital investments. The government had to borrow money, which was then pumped into the economy providing jobs. Recently, the Recovery Act of 2009 helped create new jobs by investing in education, infrastructure, health, and renewable energy resources.

Supply-Side Theory

At the other end of the economic ideological spectrum are supply-side theorists. They, too, address fiscal policy, but in a different way. Harvard economist Arthur Laffer, a key advisor to Republican President Ronald Reagan, came to define supply-side economics. Supply-sider theorists—fiscal conservatives—believe that the government should leave as much of the money supply as possible with the people, letting the laws of economics, such as supply and demand, govern the marketplace. This approach, known as laissez-faire (French for “let it be”) or free-market theory, means taxing less and leaving that money in citizens’ pockets. According to this theory, such a stance serves two purposes:

1) people will have more money to spend and will spend it, and

2) this spending will increase purchasing, jobs, and manufacturing. Under this concept, the government will still earn large revenues via the taxes collected from this spending. The more people spend, the more the state collects in sales taxes. The federal government will take in greater amounts of income tax because more people will be employed and salaries will increase. Government will also take in greater quantities of revenues in corporate taxes from company profits. Supply-siders try to determine the right level of tax to strengthen firms and increase overall government revenues.

Keeping taxes low also provides incentives for people to work more and earn more, knowing they will be able to save more money. They will also invest in other ways. If they are not spending money at the store, they may put more money into the economy with larger investments, such as purchasing stocks or bonds. These activities boost the economy and show consumer confidence.

Conservative ideologies favor this supply-side theory with its limits on government regulations and reduced taxation. The Republican Congress in late 2017 passed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, promoted by President Trump, which overhauled the tax code, temporarily lowering taxes for individuals and permanently lowering taxes for corporations. Proponents of the bill, which passed in the Senate with no votes from Democrats, argued that the lower taxes for corporations will induce them to pass some of the savings on to workers in the form of higher wages and to hire more workers, both of which would help the economy grow.

Libertarians favor even fewer government regulations. Libertarians believe the government should do no more than protect property rights and voluntary trade. Beyond that, they want to let the free market work according to its own principles.

Fiscal Policy

In addition to conflicting views on the extent of government involvement in the economy, liberals and conservatives have differing views on the tax laws that produce revenue and policies that guide government spending.

Taxing

Article I of the Constitution gives Congress the power to lay and collect taxes, but when the framers empowered Congress to lay and collect taxes, they only vaguely defined how Congress would assess and collect those taxes. For the first several decades, customs duties on imports supplied most of the government revenues. During this time, however, the federal government provided many fewer services than it does in modern times.

Congress passed the first temporary income tax to support the Union cause during the Civil War. Later, Congress instituted the first-ever peacetime income tax to support the growing federal government. In Pollock v. Farmers’ Loan and Trust (1892), the Supreme Court ruled income taxes unconstitutional because Article I did not specifically grant Congress the power to directly tax individuals’ incomes. This was a classic late-1800s ruling that exemplified the Court’s judicial activism and adherence to laissez-faire or free-market thought. It was also the ruling that brought the Sixteenth Amendment (1913), which trumped the Court and allows Congress to tax people’s incomes. Soon after, Congress began defining the income tax system and later created the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to oversee the collection process. Today, the largest share of federal revenue comes from income taxes on individuals.

Congress regularly alters the tax code for a variety of reasons. Our national income tax is a progressive tax, meaning one’s tax rate increases, or progresses, as one’s income increases. During World War II, the highest tax bracket required a small number of Americans, only those making the equivalent of $2.5 million a year in today’s dollars, to pay 94 percent of their income in tax. Since President Kennedy encouraged a major drop in the tax rate in 1962, the top tax bracket has gradually diminished. In the 1970s, the richest taxpayers paid around 70 percent. While conservative Ronald Reagan was in office in the 1980s, it fell to below 30 percent, and in the most recent decades, it has hovered between 35 and 40 percent. The Trump administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 lowered the highest individual tax bracket to 37 percent.

Congress has used taxing power not only as a revenue source but also as a way to draft social policy by encouraging certain behaviors and discouraging others. When liberals have been in charge of drafting tax laws, Congress has created incentives to encourage people to purchase energy-efficient cars, appliances, solar panels, doors, and windows for their homes in order to protect the environment. The 2017 tax reform eliminated some of those incentives while providing incentives for families who hold what many call traditional values. These incentives include increased child tax credits to encourage having children, with married couples receiving the greatest benefits.

Paying nearly 40 percent of what one earns to the national government seems high, but only the richest Americans do so. Today, only people earning hundreds of thousands of dollars per year are paying at this high rate. In fact, more than 18 million people in the United States need not even file a tax return, and well over 30 million others still end up paying no federal income tax at all. Middle-class Americans, families earning under $165,000 per year, pay roughly between 12 and 22 percent of their incomes to the federal government.

Public opinion supports a mildly progressive tax code, and that has been the standard since the Progressive Era (1890-1920). Some conservatives on the far right, however, argue for a flat tax, one that taxes citizens at the same rate. Libertarians go even further, arguing that the government should not coerce people to do anything, including paying taxes.

Spending

The budget process has become very partisan as Republicans and Democrats differ on spending priorities. Republicans tend toward fiscal conservatism; Democrats tend to spend federal dollars more liberally on social programs to help the disadvantaged or to support the arts.

The president initiates the annual budget, the plan for how revenue will be spent. Members of Congress from the party opposite the president commonly claim the president’s budget plan is “dead on arrival.” The reality is that typically both parties vote to spend more than the federal government takes in, increasing the national debt, while they argue about philosophical differences on parts of the budget that make up a fraction of the total. For example, some argue against spending money on NASA and other scientific endeavors. For the 2017 budget, all funds going to science, space exploration, and technology totaled $19.6 billion, a huge sum, but less than 1 percent of the overall budget. The National Endowment for the Arts, always a target for criticism from fiscal conservatives, was eliminated completely from President Trump’s 2018 budget proposal, as was the National Endowment for the Humanities, even though these endowments represented a mere 0.009 percent of the budget. In the final budget, however, their funding was extended. Welfare programs, a somewhat controversial slice of the federal pie, typically amount to between one and two percent.

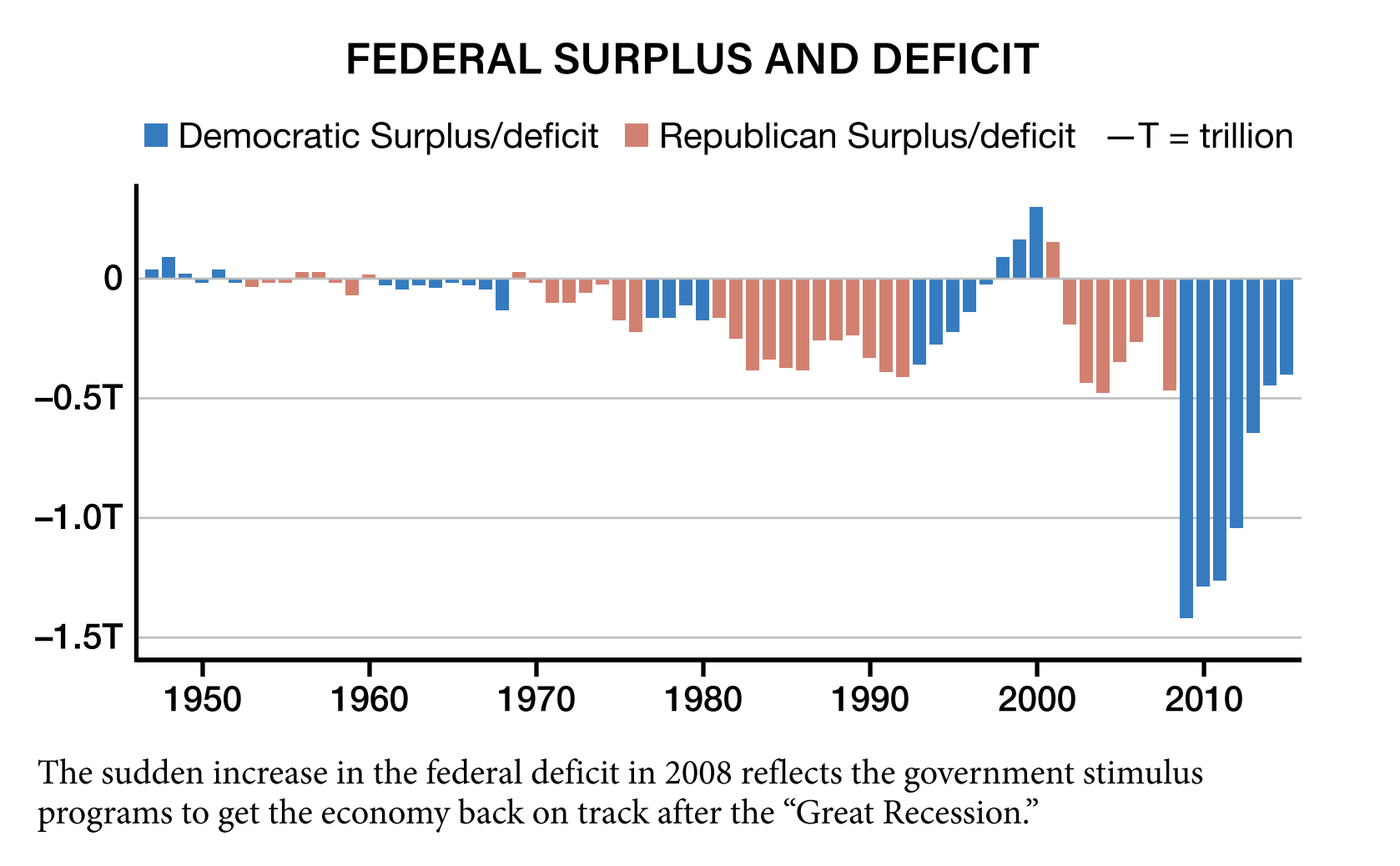

Balancing the budget—spending no more than the revenue brings in—is a nearly impossible task. Democrat Bill Clinton (1993-2001) has been the only president in recent time to balance the budget, which he accomplished with no Republican support by raising taxes on the wealthy. Neither party has been able to sustain a balanced budget with all of the demands on government spending, though Democrats have done a slightly better job.

Monetary Policy

The basic forces of supply and demand that determine prices on every product or service from lemonade to cars also determine the actual value of the U.S. dollar. Of course, a dollar is worth 100 cents, but what will it buy? Diamonds and gold are worth a lot because they are in short supply. Paper clips are cheap for the opposite reason. These same principles affect the value of money itself.

Monetary policy is how the government manages the supply and demand of its currency and thus the value of the dollar. How much a dollar is worth depends on how many printed dollars are available and how much people in both in the United States and around the world want those dollars. When there are too many dollars in circulation, inflation-rising prices and devaluation of the dollar-occurs. If a government closely monitors how much currency makes its way into circulation, the value of a dollar will remain relatively high. Conservatives tend to prefer monetary policy adjustments to regulate the economy over fiscal policies, which they tend to regard as wasteful government spending and unnecessary interference.

The Federal Reserve System

To manage the money supply, Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913. It consists of the Federal Reserve Board and 12 Federal Reserve Banks.

The Federal Reserve Board, or “The Fed, is the board of seven “governors” appointed by the president and approved by the Senate for staggered 14-year terms. One governor serves as the chairman for a four-year term. This agency sets monetary policy by buying and selling securities or bonds, regulating money reserves required at commercial banks, and setting interest rates.

The 12 Federal Reserve Banks serve as the channel for money traveling from the government printing press to the commercial banks in your hometown.

The U.S. government loans these printed dollars to the commercial banks and charges interest.

The Fed also sets the discount rate, the interest rate at which the government loans actual dollars to commercial banks. Since 1990, this rate has fluctuated from 4 to 6 percent; recently it has dropped below 1 percent. Raising or lowering the discount rate has a direct impact on commercial banking activity and the economy in general.

Commercial banks will borrow larger sums when the rate is lower and drop their interest rates accordingly in order to loan more money to its customer-borrowers. When banks can offer lower interest rates to consumers, people purchase more cars and houses. When more homes or cars are purchased, employment rises as more car sales associates, realtors, and housing contractors are needed; and demand is generated for lumber, bricks, rubber, and gasoline.

Sometimes an economy can grow too fast or too much causing inflation. The Fed can raise the discount rate, slowing the flow of dollars and ultimately placing more national money into the reserve, resulting in a drop in prices of consumer goods.

The Fed also regulates how much cash commercial banks must keep in their vaults. This amount is known as the reserve requirement. While these banks give you an incentive to keep your money with them by offering small interest rates on savings or checking accounts, they charge higher rates to those borrowing from them. The Fed sets reserve requirements, the amount of money that the bank must keep on hand as a proportion of how much money the bank rightfully possesses (though much of it is loaned out to borrowers).

This reserve requirement has a direct effect on how much the bank can loan out. If the reserve requirement declines from $16 on hand for every $100 it loans out to $12 on hand per $100, the bank will be encouraged to loan out more. If the reserve requirement rises, the interest rates will also rise.

The Fed also determines the rates for government bonds, or securities-government IOUs-and when to sell or purchase these. In addition to taxes, the federal government takes in revenue when individual citizens or even foreign governments purchase U.S. bonds or other Treasury notes on a promise that the United States will pay them back later with interest. The Fed both sells bonds to and purchases them from commercial banks. When it buys them back with interest, it is giving the banks more money with which to operate and to loan to customers.

As you can see, decisions at the Fed can have monumental impact on the value of the dollar and the state of the economy. That is why the Federal Reserve Board is an independent agency in the executive branch. Presidents can shape the Fed with appointments, but once confirmed, these federal governors and the chairman act in the best interest of the nation, not at the whims of the president or of a political party. The president cannot easily remove the governors. Their lengthy 14-year terms allow for continuity. The chairman’s four-year term staggers the president’s term to prevent making the president’s appointment to the position an election issue.

Differing Views on Monetary Policy

Supporters of monetary policy as the best stabilizing factor in an economy-mainly conservatives-look to the work of Milton Friedman and Alan Greenspan (Fed chairman from 1987-2006 as their theoretical base. Both disagree with the Keynesian analysis of the economy and have supported an “easy-money” policy of lowering interest rates to stimulate banks to loan more money, which in turn stimulates consumption and economic growth. This policy also guards against inflation. Critics of this approach, including many liberals, point to studies that show it has not had the desired effects and may have even been part of the cause of the Great Recession. During this recession housing prices fell dramatically, stranding homeowners who borrowed with easy money and then found themselves with mortgage amounts exceeding the value of their homes. Many were forced to abandon their homes and the equity they had invested.

Political Ideologies on Trade

The process of an ever-expanding and increasingly interactive world economy is known as globalization. Nations have increased their trading over the past two generations. Today, most products you find in your local department store were produced overseas. The U.S. government, mostly through Congress, can decide to increase or decrease trade with foreign nations. A government wants to encourage its firms to export to larger world markets so that wealth from other nations enters the U.S. economy. A nation that exports more than it imports has a favorable trade balance. One that purchases more goods from other nations than it sends out has a trade deficit. The size of this surplus or deficit is but one measure of U.S. economic success. On the other hand, Congress imposes import duties on products coming into the country to protect U.S. manufacturers.

According to the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 9, to encourage American production, Congress cannot tax exports. The framers did, however, expect Congress to tax imported goods, charging fees to foreign manufacturers in order to give American manufacturing an advantage. Import taxes require foreign firms to raise prices on their goods once they arrive in the United States. The idea was to create a favorable trade balance, hoping Americans would produce and export more than they imported.

Since trade has an impact on the economy, trade agreements generate ideological differences of opinion. For example, the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) lifted trade barriers among the three largest North American countries: the United States, Canada, and Mexico. This agreement effectively removed import taxes among these powers. The debate about this agreement created a battle between generally conservative corporations and generally liberal labor unions. The business community, manufacturing firms, and economic conservatives generally favor free trade.

To laissez-faire economists, lifting barriers and government interference will create a free flow of goods and services on a global scale. These same proponents of globalization argue that the process has decreased poverty and enhanced quality of life in foreign nations as well as opening new markets for U.S. goods and services.

Many laborers, however, feared that American firms would outsource their labor requirements, which they have done. The auto industry suffered a major blow over the past decade and the automakers in Detroit closed plants and laid off workers. The free traders responded that the Mexican economy has grown, and Mexico has bought more goods and services from the United States.

Ideology and Social Policy

Many people believe the goals of the Constitution are best served when the government plays a key role in providing social welfare-support for disadvantaged people to meet their basic needs. The nation’s social welfare policy has tried to provide that support, especially the New Deal programs of the 1930s and the Great Society programs of the 1960s. More recently, Congress passed and President Obama signed into law a national health care law, although it has been under attack by a Republican-dominated Congress and the Trump administration.

Social Issues and Ideology

Just as political ideologies vary on the issue of government involvement in the economy, so do they vary on the extent to which the government should address social issues. The Preamble to the Constitution declares that the government will “promote the general welfare” of its citizens. Yet opinions vary widely on the best way to accomplish that goal.

A Social Safety Net

In the liberal view of social policy, the government should provide a safety net for people in need and pay for it with higher taxes. This safety net takes the form of entitlements – government services Congress has promised by law to citizens – that are major contributors to both annual deficits and the overall debt. Congress frequently defines criteria that will award cash to individuals, groups, and state or local governments. Congress must cover this mandatory spending, paying those who are legally “entitled” to these funds. Entitlements include Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, block grants, financial aid, food stamps, money owed on bonds, and the government’s many contractual obligations.

Social Security

The largest entitlement program is Social Security. Congress passed the Social Security Act amid the Great Depression (1929-1939) to create a federal safety net for the elderly and those out of work. This program greatly expanded the role of government, creating what some call the welfare state. The economic disaster had bankrupted local charities and state treasuries, forcing the national government to act. The law created an insurance program that required the employed to pay a small contribution via a payroll tax into an insurance fund designed to assist the unemployed and to help financially strapped retirees.

Officially called Old Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI), Social Security requires most employed citizens to pay 12.4 percent (the employer pays 6.2 percent and the employee pays 6.2 percent) into a trust fund that is kept separate from the general treasury as an independent agency to protect it. The Social Security Administration handles the fund and distributes the checks. It is a large agency composed of almost 60,000 employees and more than 1,400 offices nationwide. This mandatory government-run retirement plan constitutes more than 20 percent of the budget.

Compared to the 1930s, however, Americans are living much longer, extending the time they will collect Social Security benefits. Some predict the Social Security trust fund – an account set aside and protected to help maintain the system – will become exhausted in 2042. At that time, the annual revenue for the program is projected to drop by 25 percent.

Politicians began realizing the potential hazards within this program years ago. Political daredevils have discussed privatizing the program or raising the retirement age. However, people who have paid into the system for most of their lives become upset when they hear politicians’ plans to tamper with Social Security or to suddenly change the rules. These factors have made Social Security the “third rail” of politics. Nobody wants to touch the third rail of a train track because it carries the electrical charge, and no politician wants to touch Social Security because of the shockwave in constituent disapproval that might hurt a candidate politically.

Medicare and Medicaid

Combined, Medicare and Medicaid make up nearly 20 percent of the federal budget. Medicare is a government-run health insurance program for citizens over 65 years old. Medicaid is a health care program for the impoverished who cannot afford necessary medical expenses.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s plan to pay for the elderly’s medical care was tabled until Congress passed the Medicare law in 1965 during the Democratic administration of President Lyndon Johnson. It is administered by an agency in the Department of Health and Human Services and is funded by a payroll tax of 1.45 percent paid by both employer and employee. For those earning more than $200,000 per year, the rate has recently increased to 3.8 percent. The law, which has since been amended, is broken into four parts that cover hospitalization, physicians’ services, a public-private partnership known as Medicare Advantage that allows companies to provide Medicare benefits, and a prescription drug benefit. For those over age 65 who qualify, Medicare can cover up to 80 percent of their health care costs. Many retirees carry supplemental private insurance as well. Medical expenses in the golden years can get expensive.

Medicaid provides health insurance coverage for the poorest Americans. To be eligible for Medicaid services, the applicant must meet minimum-income thresholds, have a disability, or be pregnant. Medicare and Medicaid are largely administered by the states while the federal government pays the bill.

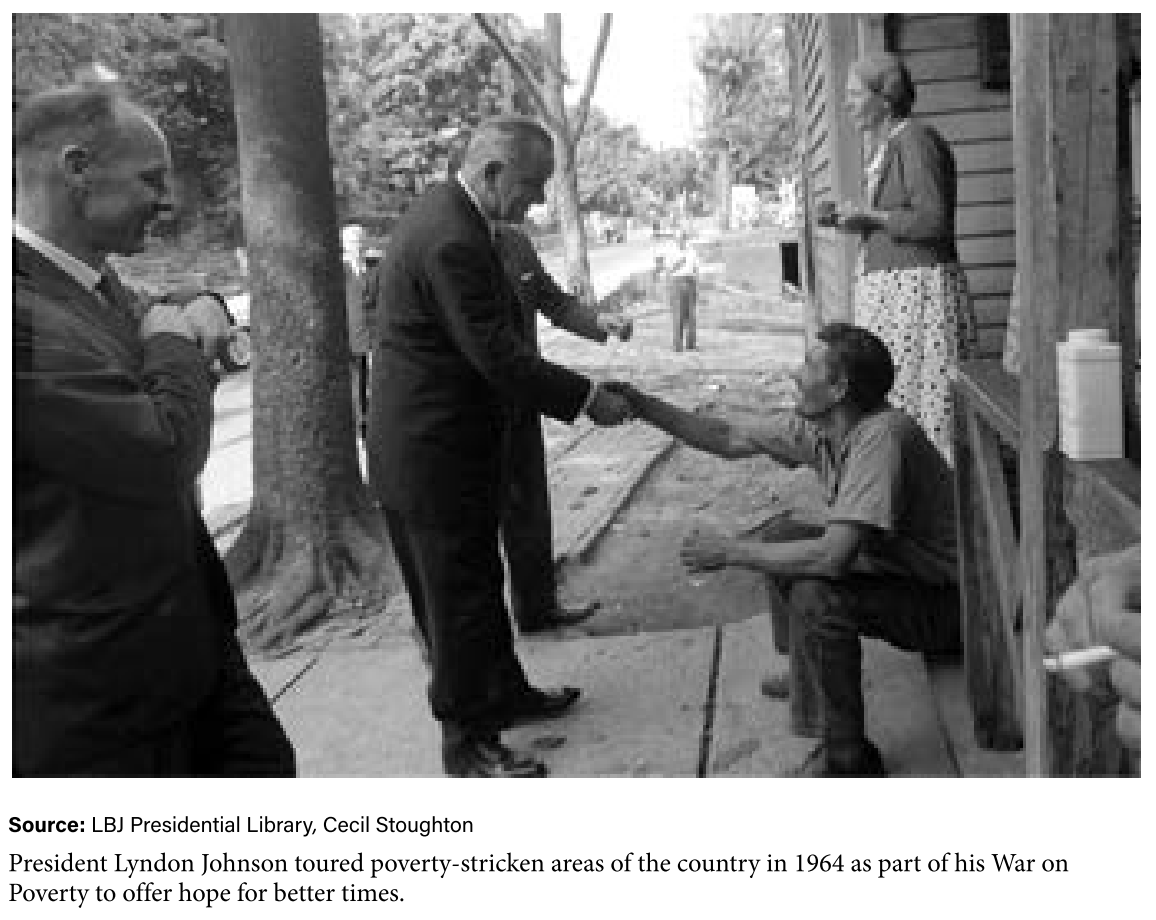

Liberals supported other measures in President Johnson’s Great Society initiative, including programs in a War on Poverty that provided additional aid for the poor, subsidized housing, and job retraining programs, with the total increasing from nearly $10 billion in 1960 to about $30 billion in 1968. The percentage of people living in poverty fell dramatically, especially among African Americans.

Conservative Opposition

Conservatives and libertarians, however, had long opposed these expensive government programs. As early as 1964, Ronald Reagan clearly articulated the conservative view in a speech supporting the candidacy of Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater. Reagan said, “the Founding Fathers knew a government can’t control the economy without controlling people. And they knew when a government sets out to do that, it must use force and coercion to achieve its purpose.”

When Reagan became president in 1981, he built on efforts he made while governor of California to cut back on government social spending. “Reaganomics,” as the economic programs of Reagan have come to be called, stressed lowering taxes and supporting free market activity. With lower taxes, welfare programs such as the food stamp program and construction of public housing were cut back.

Health Care

American citizens purchase health insurance coverage either through their employer or on their own. Health insurance eases the cost of doctor visits, prescription medicines, operations, and other medical costs.

Many politicians and several presidents have favored the idea of a government-based health care system for decades. Some health insurance regulations have existed for years, sometimes differing from state to state. Recently, with the continual increases in insurance prices and the diminishing level of coverage, more people have bought into the idea of expanding government regulation of health insurance and making the service more affordable.

This idea finally became law with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010. Sometimes referred to as “Obamacare” because of President Obama’s initiative for the law, the comprehensive Affordable Care Act (ACA) became a divisive issue in party politics, with opponents concerned about the overreach of government. Conservative legislators, many of them backed by wealthy campaign donors with libertarian leanings, objected to the government’s involvement in health care and fought the bill fiercely. Conservatives tend to believe that private companies can do a better job providing social services, including health care, than the government. They push for privatization of Medicare and Medicaid as a way to reduce mandatory spending and to energize the private sector. In their view, privatizing health care would increase competition among providers, which in turn will lead to generally lower health care costs.

Popularity of this law and program has increased gradually since its passage. A range of polls on whether Americans favor or oppose the ACA as of late 2019 show a noticeable favorability, ranging from 2- to 9-point differential.

Labor

As an economic issue, conservatives tend to view labor as an element of the free market that should not be regulated by the government. Wages, according to this view, should be determined by supply and demand. Liberals, in contrast, view labor as a unique element in the marketplace because of the complexities of human behavior. For example, workers with higher wages tend to be more motivated to do a good job and remain with an employer longer than workers with lower wages, factors not considered in the supply-and-demand model.

Conservatives tend to view organized labor as a negative influence. In some states and at some places of business, whether they want to join a union or not, workers are required to pay union dues. Many people believe that such requirements are an infringement of their individual liberties, especially since labor unions actively campaign for candidates and not all workers support the candidates the unions endorse. Liberals have a much more positive view of organized labor as a force that has lifted workers into a position of some power through collective bargaining, which has resulted in the 40-hour work week, employer-provided health care, and many other benefits.

Corporations and workers struggled as the labor union movement developed from the late 1800s into the Great Depression. During periods of liberal or progressive domination of the federal government, Congress passed various laws that prevented collusion by corporations, price fixing, trusts, and yellow dog contracts (forcing newly hired employees into a promise not to join a labor union). As part of the New Deal program, Congress passed the Wagner Act (1935), which created a federal executive branch commission that regulates labor organizations and rules on alleged unfair labor practices. A second law established minimum wage, defined the 40-hour work week, and required companies to pay employees overtime pay.

After World War II, Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1946 mid-term elections and passed the Taft-Hartley Act (1947), generally favored by business and partly counteracting the labor movement. It enabled states to outlaw the closed shop—a company policy or labor contract that requires all employees to join the local union. States could now pass “right to work” laws, and by 2020, 28 states have.

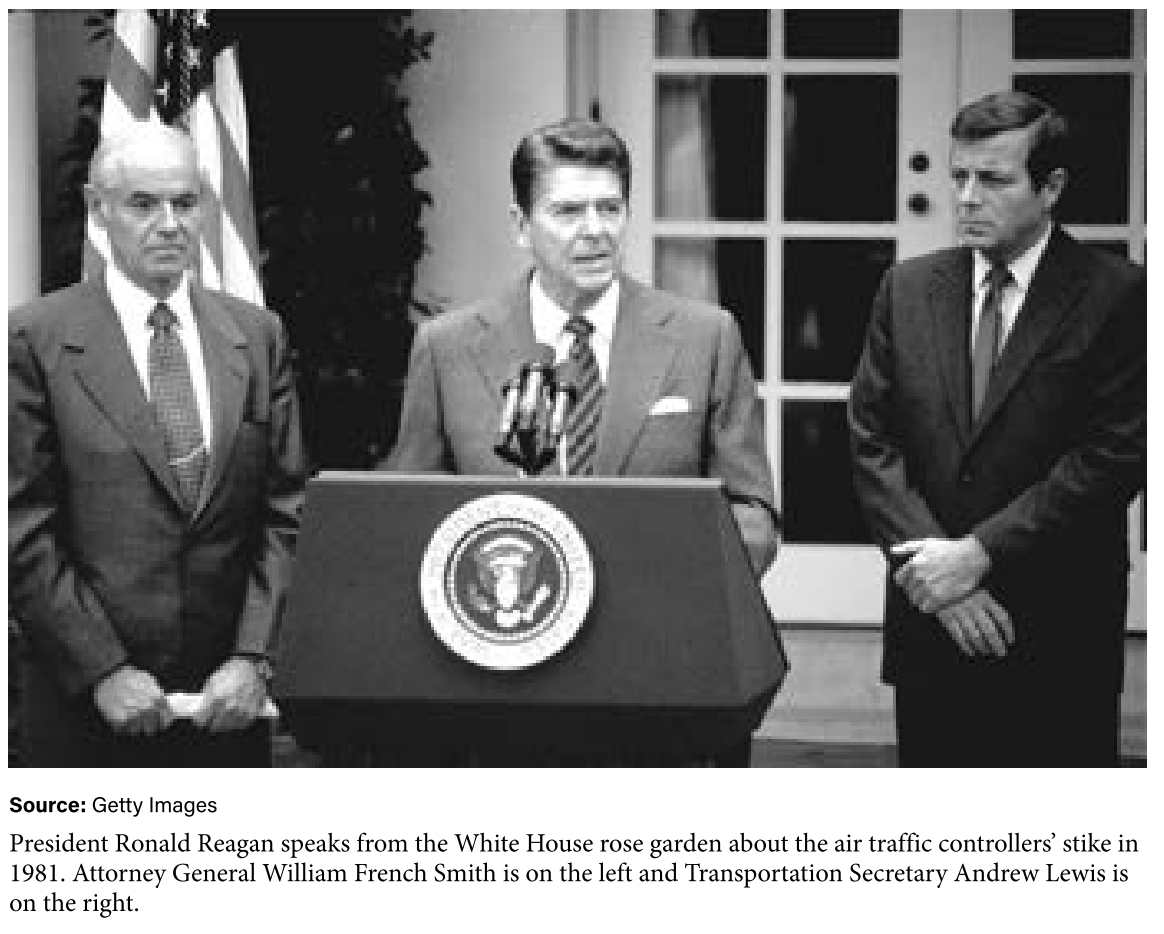

During the conservative presidency of Ronald Reagan, however, organized labor received a blow that has been hard to overcome. Reagan spoke out against the August 1981 strike by air traffic controllers. He declared the strike illegal because the controllers were public employees, and he fired them. Their union was later decertified. Reagan was, in general, a supporter of workers’ rights to collective bargaining, but his firm stand against the air traffic controllers, according to labor expert Joseph A. McCartin, “shaped the world of the modern workplace, which has seen dramatically fewer participants in labor walkouts.”

Ideological Differences on Government and Privacy

Other social issues besides government spending and labor also divide liberals and conservatives. These concern matters related to personal choice and individual freedoms. Liberals tend to think that the government should not regulate private, personal matters, while many modern social conservatives believe the government needs to protect core values even if doing so intrudes on some individual freedoms.

Privacy and Intimacy

Many of the issues that divide liberals and conservatives on privacy relate to intimate decisions. With the 1965 ruling in Griswold v. Connecticut (see Topic 3.9), the Court established a precedent for a right to privacy on intimate matters. That decision found that a Connecticut state law forbidding married persons from using contraception and forbidding people such as health care professionals from helping or advising someone else to use contraception was unconstitutional. The decision enshrined a right to privacy in the Bill of Rights that led to later decisions that prevented states from outlawing abortion and same-sex marriage.

Conservatives tend to believe that if the states pass laws in these areas of personal privacy, the federal government does not have authority to overrule them since the right to privacy is not explicit in the Constitution. A number of recent cases highlight the difference between liberal and conservative views on privacy. For example, does the federal government through the Supreme Court have a right to overrule a state law that requires transgender people to use public bathrooms that match their birth sex rather than their gender identity? Conservatives argue that the state law should stand. Some students argue that being forced to use a school bathroom with people of the opposite physical sex violates their right to privacy. Conservatives have pushed for the so-called bathroom bills, sometimes with dubious constitutionality that could violate rights to privacy.

Education and Religion

On matters related to education and religion, conservatives and liberals often diverge on the level of government involvement. Conservatives generally advocate for less government interference in education, favoring parental choice and supporting alternatives like private schools, many of which are affiliated with religious organizations. They argue that parents should have the freedom to choose the educational environment and curriculum that aligns with their values, often supporting voucher programs that redirect public funds to private schools.

This perspective contrasts with the liberal stance, which values strong public education systems funded by taxpayer dollars. Liberals argue that diverting funds away from public schools weakens the system and reduces educational equity. They prioritize inclusive educational environments that cater to diverse student needs and backgrounds, aiming for universal access to quality education.

Similarly, conservatives tend to oppose government intervention in religious practices, particularly when it conflicts with personal beliefs. For instance, some businesses, citing religious objections, have refused services to same-sex couples for weddings. Conservatives argue that individuals and businesses should have the right to practice their religion freely without government interference, even if their beliefs clash with federal anti-discrimination laws.

In contrast, liberals emphasize equal treatment under the law, advocating for protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation or other factors. They support measures that prevent businesses from denying services to customers based on personal beliefs, arguing that such practices can perpetuate discrimination and inequality.

Recent Supreme Court cases, like Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2017) and subsequent rulings, highlight the ongoing legal and ideological tensions between religious freedoms and anti-discrimination protections. These cases reflect broader societal debates over the balance between individual rights, religious liberty, and equal treatment under the law.

Public policy at any time is a reflection of the success of liberal or conservative perspectives in political parties. When Republicans are in power, conservative policies on marketplace regulation, social services, and privacy are often voted or adjudicated into law. When Democrats are in power, they tend to promote liberal social, economic, and privacy policies.