Presidential Elections:

nominations & primary elections

open vs closed primary

caucuses

national convention

incumbent

incumbent advantage

Electoral College:

congressional reps x 2

270 electoral votes

faithless elector

popular vote vs. electoral college

proponent/opponent debate

Congressional Elections:

2 years

midterms

incumbent advantage

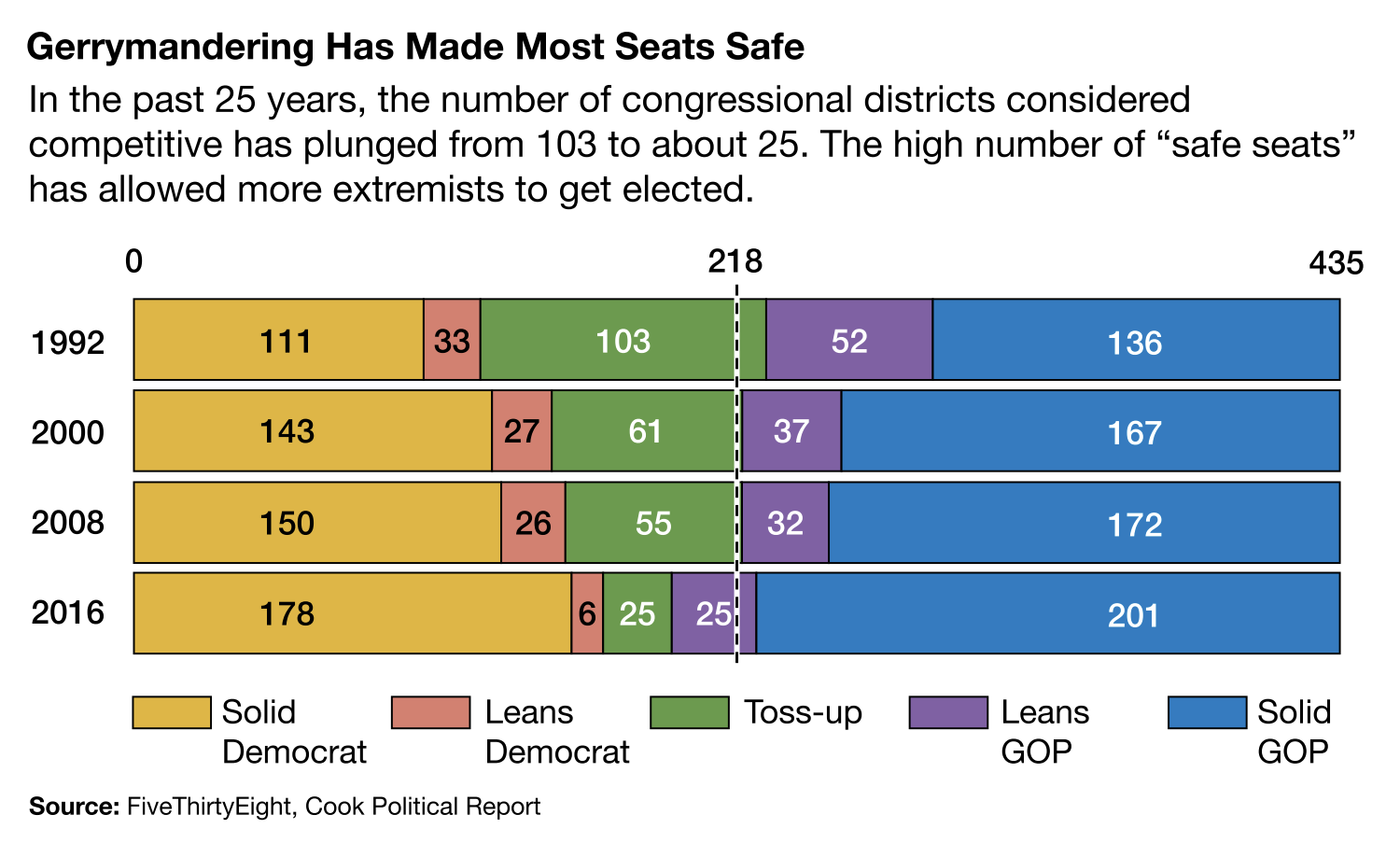

safe districts/gerrymandering

primary v general

Every four years in November, millions of Americans go to the polls to cast a vote for the American president and other offices. Sometimes a candidate will win in a landslide with a strong margin and claim victory before sunset. Sometimes close elections require careful vote counting, and a victor is not declared for days. In November 2016, United States citizens, through the nation’s complex electoral system, elected Donald Trump president. Popular sovereignty, individualism, and republicanism are important considerations of U.S. laws and policymaking and assume citizens will engage and participate.

Road to the White House

The U.S. presidential race is more complex and more involved than any other election. The road to the White House is long and arduous, with layers of rules and varying state election laws. A presidential campaign requires two or more years of advance work to make it through two fierce competitions—securing the party’s nomination and winning a majority of states’ electoral votes. Before presidential hopefuls formally announce their candidacy, they test the waters. Most start early, touring the country and making television appearances. Some author a book, typically a memoir that relies heavily on their political philosophy. As the election year approaches, announced and unannounced candidates compete in the invisible primary (sometimes called the media primary or the money primary), as public opinion polls and comparisons of fundraising abilities begin to tell the score long before the first states have voted.

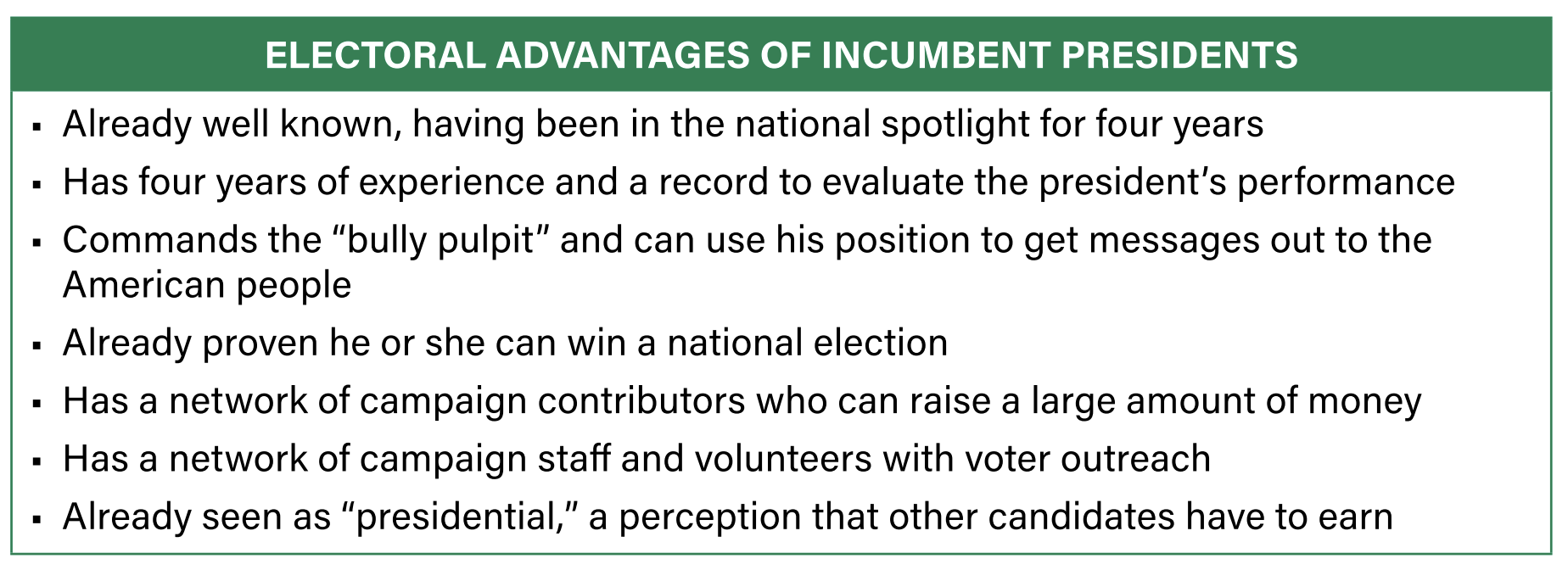

Incumbent Advantage Phenomenon

An incumbent president—one already holding the office—seeking a second term has a much easier time securing the nomination than a challenger because of the incumbent advantage phenomenon—the ability to use all the tools of the presidency to support candidacy for a second term. At the end of a president’s second term, the field opens up again for candidates since the president has served as long as he or she can. The rate of reelection for incumbents is high, about 80 percent.

Primaries and Caucuses

To win the presidential nomination, candidates must first win state primary elections or caucuses. Technically, citizen-voters in these contests cast votes for delegates to attend the party’s national convention. With their vote, the citizen-voters advise those delegates whom to nominate at that national convention.

The Republican and Democratic rules for nomination differ, but both require a majority of votes by the appointed delegates at the convention. To win the nomination, candidates must win the requisite number of these state contests from January into the summer.

Types of Primaries

Today, most states hold a primary election. For years, the closed primary was standard. In a closed primary, voters must declare their party affiliation in advance of the election, typically when they register to vote. The open primary, used by about half of the states today, allows voters to declare party affiliation on election day. Poll workers hand these voters one party’s ballot from which they select candidates.

The rarest primary is the blanket primary. California and other western states pioneered the blanket primary, which allows voters to cast votes for candidates in multiple parties. In other words, voters can cast a split ticket, picking Republicans in some races and Democrats in others. California voters instituted a nonpartisan primary in 2010. This new runoff system includes all candidates—both party members and independents. The top two vote-getters, regardless of party affiliation, compete for office in the general election. The quest for inclusiveness created a unique dynamic that caused the press to dub it the “jungle primary” because the winners emerge through the law of the jungle—survival of the fittest without regard to party.

Iowa Caucuses

A few states use caucuses to nominate presidential candidates. Since 1976, the Iowa caucuses have taken place before any other state nominating elections. Caucuses differ from primary elections. Across Iowa, rank-and-file party members meet at community centers, schools, and private homes where they listen to endorsement speeches, discuss candidates, and then finally cast their vote before leaving the caucus. In comparison to standard elections, caucuses are less convenient and more public. This two-hour commitment makes attendance challenging for some. Others dislike the public discussion and the somewhat public vote (voters usually cast a vote at a table set aside for their candidate). So, those who do show up at caucuses tend to be more dedicated voters who hold strong opinions and often fall on the far left or far right of the ideological spectrum, thus causing more liberal or more conservative figures to win the delegates from those states.

In 2020, three GOP officials—former Massachusetts governor William Weld and former Congress members Mark Sanford and Joe Walsh—tried to mount challenges against the incumbent Donald Trump, but to no avail. On the Democrat side at the Iowa caucuses, candidate Pete Buttigieg won 26.2 percent of the vote, Senator Bernie Sanders won 26.1 percent, and Elizabeth Warren won 18 percent. The remainder was split among several other candidates.

New Hampshire Primaries

New Hampshire typically follows Iowa on the primary schedule. Candidates travel the state and hold town hall forums. They campaign in grocery stores and on the streets of relatively small New Hampshire towns. During this time, the voters actively engage these presidential candidates. When asked his or her opinion on a particular candidate, a typical New Hampshire voter might respond, “I don’t know if I’m comfortable with him; I’ve only met him twice.”

This contest has such great influence that candidates cautiously frame their primary election night speeches to paint themselves as front-runners. In 1992, the news came to light that Bill Clinton had been part of a sex scandal when he was governor of Arkansas, but he survived his diminished poll numbers to earn a second-place spot in New Hampshire. During his speech late that night, Clinton confidently referred to himself as “The Comeback Kid.” This sound bite made its way into headlines that gave the impression that Clinton had actually won the New Hampshire primary.

In the 2020 Democratic primary in New Hampshire, Bernie Sanders bested Pete Buttigieg, 25.7 percent to 24.4 percent. Each man received 9 delegates.

Iowa and New Hampshire receive immense national attention during their primaries. Campaign teams and the national media converge on these states well in advance of election day. Politically, these states hold more influence than those that conduct their elections much later. This reality has brought on front-loading—states scheduling their primaries and caucuses earlier and earlier to boost their political clout and to enhance their tourism. Iowa and New Hampshire have followed suit and leapfrogged those other states to continue to be first and second. The national party committees also shape and influence the schedule, and for the foreseeable future, those states will begin the contests.

Candidates then travel an uncertain path through several more states, hoping to secure enough delegates to win the nomination. In recent years, South Carolina has followed New Hampshire and has served as a barometer for the southern voting bloc. More conservative GOP primary voters will now impact that nomination, and the large African American voting bloc will influence the Democrats’ quest. In the 2020 South Carolina primary, U.S. House whip and African-American Jim Clyburn publicly endorsed Biden in a powerful message. “I know Joe. We know Joe. But more importantly, Joe knows us.” It helped Biden win more than 48 percent of the vote; Sanders received less than 20 percent. Democrats began to withdraw and eventually united behind Biden.

A few weeks later, several states coincidentally hold primaries on Super Tuesday (so known because of the large number of primaries that take place on that day), when the race narrows and voters start to converge around fewer, or perhaps just one nominee.

According to a Pew study, since 1980, voter turnout in presidential primaries has ranged from 15 to 30 percent of the voting-eligible population. In 2016, about 57.6 million primary voters, or about 28.5 percent of the estimated eligible voters, voted in Republican and Democratic primaries.

Party Conventions

The national party conventions have become less suspenseful in modern times because the nominees are determined long before the convention date. Both parties have altered rules and formulas for state delegation strength.

States determine their convention delegates in different ways and hold them to different rules. Some states give their delegates complete independence at the convention. Some presidential primaries are binding on “pledged delegates.” Even in those cases, states differ on how these delegates are awarded.

Some operate by congressional district. Some use a statewide winner-take-all system, and some use proportional distribution for assigning delegates. For instance, in a proportional system, if Candidate A receives 60 percent and Candidate B receives 40 percent of the popular primary vote, the state sends the corresponding percentage of delegates for each candidate to the national gathering. The parties at the state and national level change their rules at least slightly every election cycle. The Democrats’ use of superdelegates—an unelected delegate who can support any candidate—also leaves room for uncertainty in the process.

When assigning superdelegates, Democrats take into account the strength of each state’s electoral vote and compare it to the record of how the state has cast votes for Democratic candidates in past general elections. Republicans place more value on the number of GOP representatives in Congress from those states and whether states have cast their electoral votes for Republican presidential candidates. In other words, Democrats give more delegates to large states, while Republicans give extra delegates to loyal states. Democrats have also instituted the idea of fair reflection to balance delegates by age, gender, and race in relation to the superdelegates or party elders.

The General Election

The general election season starts after party nominations and kicks into high gear after Labor Day. Candidates fly around the country, stopping at key locations to deliver speeches. As the public and press begin to compare the two major party candidates, the issues become more sharply defined. Different groups and surrogates (spokespersons) support each candidate and appear on television.

The major party candidates debate, usually in three televised events over the course of several weeks. The vice presidential candidates usually debate once.

Major newspapers endorse a candidate in their editorial pages. The media’s daily coverage provides constant updates about which candidate is ahead as measured by public opinion polls and campaign funding. By November, candidates have traveled to most states and have spent millions of dollars.

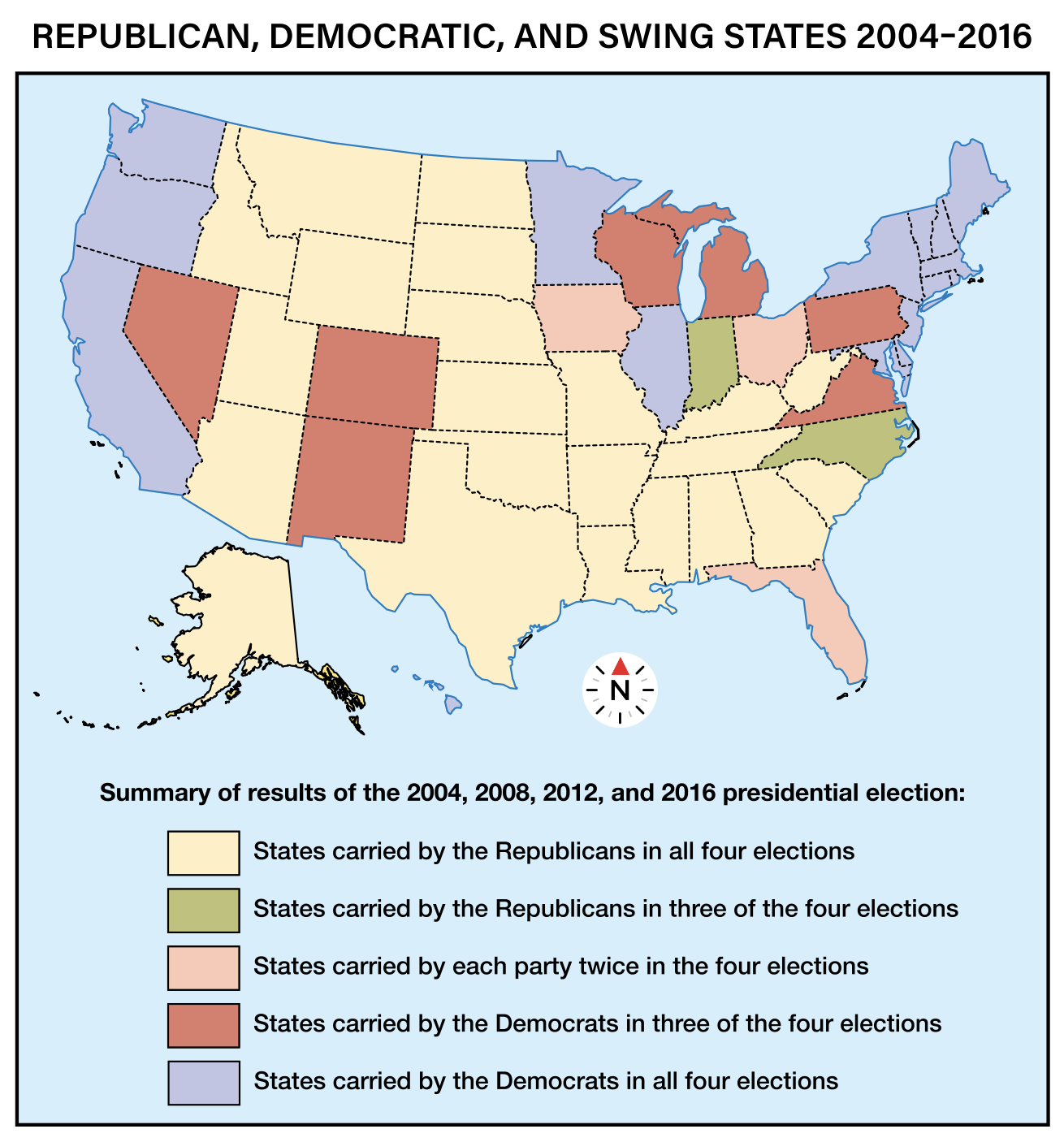

Where candidates spend those millions depends on where they have the best chance to influence outcomes. Republicans and Democrats live in all 50 states, but in some states, Republicans have a long history of being victorious, while in others, Democrats often win. The patterns have changed in the last generation, but in recent times, the so-called “red states,” those in which Republicans usually win, and “blue states,” those in which Democrats usually win, have remained fairly constant.

However, some states have a less predictable pattern. They are known as swing states because the victories swing from one party to another in different elections. Candidates concentrate their campaign resources in those states. While they travel to most of the states meeting with wealthy donors to raise money, they focus on swing states by holding campaign events and spending advertising money.

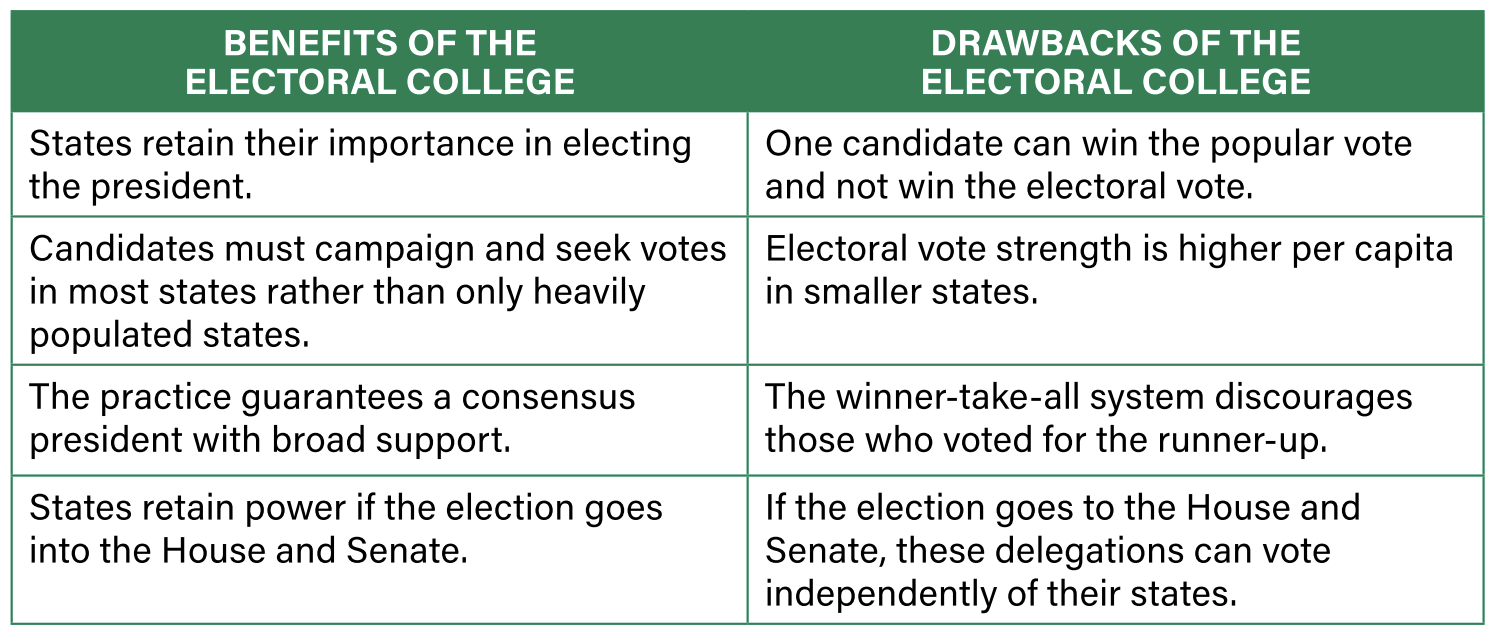

Electoral College

The Electoral College system is both a revered and a frustrating part of the presidential election because it shapes a presidential candidate’s strategy. The system to elect the president has several features. The “college” is actually a simultaneous gathering of electors in their respective capital cities to vote on the same day. The framers devised this system to temper public opinion and to allow the more informed statesmen to select a consensus president. State and federal law as well as party custom also affect the process. Each state receives the same number of electors (or electoral votes) as it has members of Congress; however, these electors cannot be U.S. senators or representatives.

Originally, the Constitution provided that each elector cast one vote for each of his or her top two choices for president. The winner became president and the runner-up became vice president. The Twelfth Amendment (1804) altered the system so that electors cast one vote for president and another for vice president. To win, candidates must earn a majority of the electoral votes. Since the Twenty-third Amendment (1961), Washington, D.C., adds three electoral votes. This brings the vote total to 538: 435 to align with the House total, plus 100 to match the total Senate seats, plus the three for D.C.

The candidate who earns 270 electoral votes, a simple majority, will become president. If no presidential candidate receives a majority, then the U.S. House of Representatives votes for president by delegations, choosing from among the top three candidates. Each state casts one vote for president, and whichever candidate receives 26 states or more wins. The Senate then determines the vice president in the same manner.

Winner-Take-All

Today, most states require their pledged electors (people already committed to a party’s ticket) to follow the state’s popular vote. Besides, electors are typically long-time partisans or career politicians who are ultimately appointed by the state party. The candidate who wins the plurality of the popular vote (the most, even if not the majority) in a given state will ultimately receive all of that state’s electoral votes. This is known as the winner-take-all system. Only Nebraska and Maine allow for a split in their electoral votes and award electors by congressional district rather than on a statewide basis.

In early December, electors meet in state capitals and cast their votes. The ballots are transported to Washington in locked boxes. When Congress opens in January, the sitting vice president and Speaker of the House count these votes before a joint session of Congress. Since most states now require their electors to follow the popular vote, the electoral vote total essentially becomes known on election night in November. Television media coverage typically shows a U.S. map with Republican victories depicted in red and Democratic victories in blue. Soon after popular votes are tabulated, losing candidates publicly concede and the winner gives a victory speech. The constitutionally required procedures that follow—states’ electors voting in December and the Congress counting those votes in January—thus become more formal ceremonies than suspenseful events.

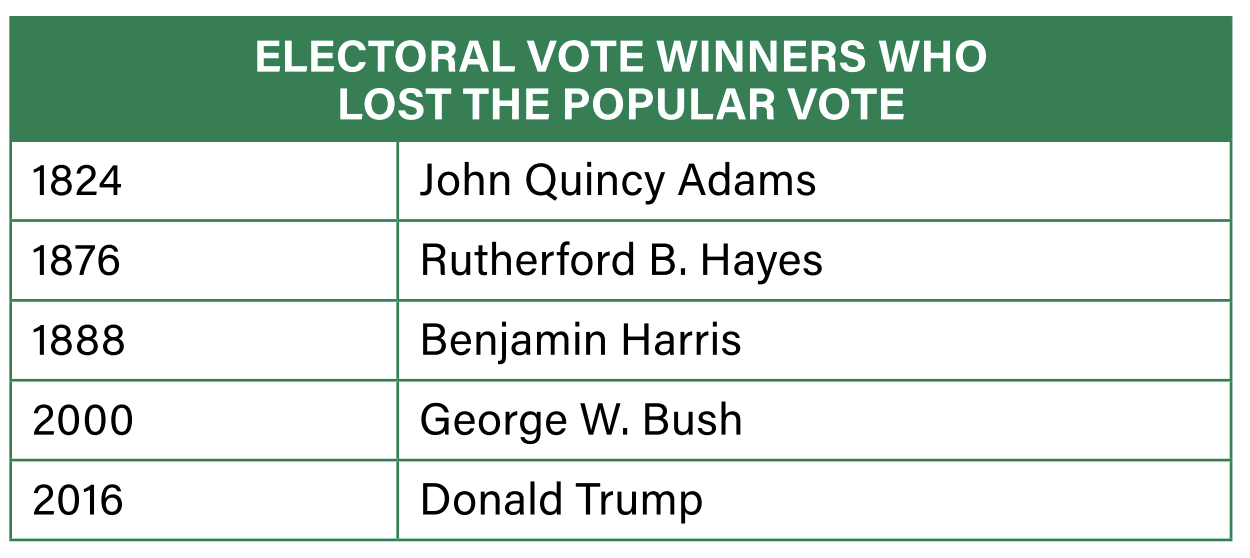

Five times in American history, the winner of the popular vote did not win the electoral vote. Hillary Clinton’s loss to Donald Trump in 2016 is the most recent example. This possibility has led some to criticize the Electoral College system. Others see the process as a way to ensure balance and to guarantee that a consensus candidate becomes president. Gallup has found that more than 60 percent of those polled want a constitutional amendment to change the electoral system, while only about 33 percent want to keep it in its current form. A proposed constitutional amendment to scrap the system and replace it with a popular vote has been offered repeatedly in Congress for years.

Congressional Elections

Congress has set federal elections to occur every two years, in even-numbered years, on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Congressional and presidential terms begin the next January. Each state has a slightly different method for congressional candidates to get their names on the ballot, but typically a number of signatures are required and some fees apply. In most states, a candidate must first win one primary election to earn the right to run as the party nominee. The candidate must follow both federal and state law. State governments have drawn congressional districts to maximize party control and, in the process, have contributed to preserving congressional seats for members for long tenures. Much has changed about congressional elections since the notable 1858 Lincoln-Douglas contest, but those debates and the focus on that Senate election shows how important they can be.

Congressional Elections

All House seats and one-third of Senate seats are up for election every two years. Federal elections that take place halfway through a president’s term are called midterm elections. Midterm elections receive a fraction of the media attention, and usually fewer voters cast ballots. However, the 2018 midterm elections had 53 percent of eligible voters participate, representing an 11-point jump from 2014. The Council of State Governments reports that since 1972, voter turnout in midterm elections is on average 17 points lower than in presidential elections. Yet, in terms of policymaking, these campaigns are important and deserve attention.

To compete in a modern campaign for the U.S. House or Senate, a candidate must create a networked organization that resembles a small company, spend much of his or her own money, solicit hundreds of contributions, and sacrifice many hours and days. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) explains that a candidate “must hire a staff and make wise use of volunteers, craft a cogent, clear message, budget carefully in spending money on mail, radio, television and printed material, and be able to successfully sell the product—himself—to the public and to the media.” Large campaigns divide these tasks into several categories, such as management, public relations, research, fundraising, advertising, and voter mobilization.

The Advantage of Incumbency

Even more so than presidential candidates, the incumbent in congressional elections has an advantage over a challenger. With rare exception, a congressional incumbent has a stronger chance of winning than the challenger. The incumbent’s financial and electoral advantage is so daunting to challengers that it often dissuades viable candidates from ever entering the race. House incumbents tend to win reelection more than 90 percent of the time. Senators have an incumbency advantage too, but theirs is not quite as strong. Incumbents capitalize on their popularity and war chest, showering their districts with mail and email throughout the congressional term. During campaign season, they purchase commercials and load up their district with yard signs while ignoring their opponent and sometimes refusing to take part in public debates.

Incumbents have several built-in advantages. Name recognition is a powerful factor. For two or more years, congressional incumbents have appeared in the news, advocated legislation, and sent newsletters back to constituent voters. Nine out of ten voters recognize their House member’s name, while fewer than six out of ten recognize that of the challenger.

Incumbents nearly always have more money than challengers because they are highly visible and often popular, and they can exploit the advantages of the office. They also already have a donor network established. Political action committees (PACs), formal groups formed around a similar interest, donate heavily to incumbents. PACs give $12 to an incumbent for every $1 they donate to a challenger.

Party leaders and the Congressional Campaign Committees realize the advantage incumbents have and invariably support the incumbent when he or she is challenged in a primary. In the general elections, House representatives receive roughly three times more money than their challengers.

Challengers receive a mere 9 percent of their donations from PACs, while House incumbents collect about 39 percent of their receipts from these groups.

A substantial number of incumbents keep a small campaign staff or campaign office between elections. Officeholders can provide services to constituents, including answering questions about issues of concern to voters, such as Medicare payments and bringing more federal dollars back home.

Certainly not all incumbents win. A bad economy will decrease incumbents’ chances, because in hard economic times, the voting public holds incumbents and their party responsible. Regardless of the condition of the economy, the president’s party usually loses some seats in Congress during midterms, especially during the president’s second term. The 2018 midterm elections illustrate these points with Democrats gaining a majority in the House by winning 41 seats. Based on results from five recent midterm elections, the president’s party lost an average of 26.4 House seats and 3.6 Senate seats.

During presidential election years, congressional candidates can often ride the popularity of their party’s presidential candidate. When a Democrat presidential candidate wins by wide margins, fellow Democratic congressional candidates down the ballot typically do well also, or the coattail effect.

Districts and Primaries

Legislative elections in several states have resulted in one-party rule in the statehouse. When drawing congressional districts for the reapportionment of the U.S. House, these legislatures have gerrymandered congressional districts into one-party dominant units. This situation dampens competitiveness in the general election. In 2016, only 33 House races, less than 10 percent, were decided by 10 points or less. Nearly three-quarters of all House seats were decided by 20 points or more.

These “safe” districts make House incumbents unresponsive to citizens outside their party, and they have shifted the competition to the primary election. Several candidates from the majority party will emerge for an open seat, all trying to look more partisan than their competitors, while one or two sacrificial candidates from the minority party will run a grassroots campaign. When House incumbents do not act with sufficient partisan unity, candidates will run against them, running to their ideological extreme.

2020 Congressional Elections

At the end of the 2020 election cycle for the House of Representatives, Democrats held 222 seats to the Republicans’ 213. An overall victory for Democrats, but a gain for Republicans from the 2018 mid-terms when the Democrats won 235 seats to the Republicans’ 199. President Biden lacked coattails. He beat Trump by 4.5 percent or 7.1 million votes, yet the Democrats lost 13 House seats. Nationwide, Republican House candidates received 1.4 million fewer votes than Trump. Democrat candidates received 3.9 million fewer votes than Biden. More voters wanted Biden as their president than wanted the local Democrat representing them in the House. Conversely, many casting Republican votes in House races did not want Trump to be their president.

The GOP recruited and funded 96 female candidates, nearly double the number from 2018. Of the Republicans who took away Democratic seats, 11 of 14 were women. The GOP also nominated 76 nonwhite candidates, up from 53 in 2018. Incumbency advantage remained high.

The Georgia Senate Races

In the Senate, 35 seats were up for grabs. Democrats took four from Republicans. The final two were highly publicized and highly competitive elections in Georgia. Incumbent Republican Senators Kelly Loeffler and David Perdue faced off, respectively, against Democrats Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff. In neither contest did a candidate receive a majority (over 50 percent), and thus Georgia law required a runoff election. Both runoffs were set for January 5. With the control of the Senate hanging in the balance, the media and the money poured into Georgia. In total, over $900 million was spent by all candidates and outside groups in these two races. Voter turnout dropped—there were 467,273 fewer ballots cast in the Perdue-Ossoff election in January than in November. This time Ossoff defeated Perdue 50.6 to 49.4 percent and Warnock defeated Loeffler 51.0 to 49.0 percent. The Democrat victories in both runoff elections left the Senate with 50 Democrats and 50 Republicans.