Interest Group Roles:

education

lobbying

drafting legislation/policy

mobilizing

social movements

protest movements

Need to Know:

iron triangle

issue network

single issue interest group

Interest Group Efficacy:

political & financial resources inequality

free rider problem

At any level of government, people differ on the question of how to shape the law and the delivery of government services. Some citizens naturally become part of formal groups based on their common beliefs. James Madison and other founders expressed concern about factions, groups of “interested” people motivated by the pursuit of wealth, religious beliefs, or alliances with other countries.

Today, these special interests are known as interest groups, or lobbies, and are concerned with corporate profits, workers’ rights, the environment, product safety, or other issues. They are linkage institutions because they connect citizens to government and provide organizations through which citizen voices can be heard.

Historic and recent accounts of bribery, scandal, and other unethical behavior have shaped the public’s impression of these groups. Yet, the First Amendment guarantees the right of special interests to operate and express opinions.

Benefits of Interest Groups

Since Madison wrote Federalist No. 10, United States political beliefs have developed into a complex web of viewpoints, each seeking to influence government at the national, state, and local levels. The nation’s constitutional arrangement of government encourages voices in all three branches of government and at all three levels. This pluralism, a multitude of views that ultimately results in a consensus on some issues, has intensified the ongoing competition among interests to influence policy. Yet, the competition ensures distribution of political power to all and not just the elite and powerful.

The three separate and equal branches of government, Madison argued in Federalist No. 10, would prevent the domination and influence of factions or interests. The American system of federalism, however, with policymaking bodies in multiple branches within state and federal governments, has created many access points and thus encouraged the rise of interest groups.

Modern interest groups have become adept at influencing policies in all three branches. Within each branch there are people and entities-individual members of Congress, a president’s appointed staff, agency directors, and scores of federal courts-that have helped to increase the influence of special interest groups.

The division of powers among national and state governments has also encouraged lobbying, applying pressure to influence government, not only in Washington but also in every state capital. The term evolved from the last place citizens could access and hopefully convince lawmakers before they voted-the lobby outside the House of Commons, Congress, or the local city council room.

State governments are based on the federal model: within each state branch are a multi-member legislature, state agencies, and various courts, all of which provide targets for interest groups. County and city governments also make important local-level decisions on school funding, road construction, fire departments, water works, and garbage collection. Many of the national interest groups, such as the Fraternal Order of Police or national teachers’ unions, have local chapters to influence local decisions. Thus, interests have an incentive to meet not only with national and state legislators but also with mayors, county administrators, and city council members.

Multiple actors and institutions interact to produce and implement possible policies.

Interest groups must compete in the marketplace of ideas just as products must compete in a free enterprise system. This competition tends to increase democratic participation, since people cannot take for granted that their interests will be considered. Interest groups also devote time and resources to creating practical solutions to real problems and have the power to get their solutions accepted. In exercising those benefits, interest groups also educate the public and use their resources to mobilize support for their point of view. They draft legislation and work with lawmakers and government agencies to see it put into law.

Some interest groups represent broad issues, such as civil rights or economic reform. Others, such as those focusing on eliminating drunk driving or preserving gun rights, represent very specific or narrow interests. Both types form in response to changing times and circumstances and both demonstrate the benefits of interest groups-their ability to have their voices heard, gain support for their position, and influence government policies and elections.

Interest groups, along with the protest movements that sometimes brought them into being, form with the goal of making an impact on society and influencing policy.

Drawbacks of Interest Groups

Interest groups have many benefits but have also been the subject of much criticism. President Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921) often expressed his frustration over the tactics used by lobbyists. “Washington has seldom seen so numerous, so industrious, or so insidious a lobby,” he once lamented when corporations opposed his tariff bill. “The newspapers are being filled with paid advertisements calculated to mislead the judgments of public men.”

In the 1930s, Senator Hugo Black (D-AL) investigated one utility company’s lobbying effort, as recounted by Kenneth Crawford in The Pressure Boys. Senator Black became suspicious when very similarly worded letters opposing a bill to regulate electric utilities began to flood Capitol Hill. Black exposed the scheme where a gas and electric company had paid telegraph messengers to persuade Pennsylvania citizens to send telegrams opposing the bill to their member of Congress. The company provided the talking points for the messages. One congressional member received 816 of these telegrams in two days, mostly from citizens with last names that began with A, B, or C. As it turned out, names had been pulled from a phone book starting from the beginning.

“The lobby has reached such a position of power that it threatens government itself,” an outraged Senator Black said in a radio address. To Black’s dismay, it turned out that the utility company had done nothing illegal, and this tactic continues today with email and social media. Interest groups send members and supporters legislative alerts when an issue of concern arises. Along with the alerts, they send sample messages for supporters to use as a base for writing their own messages, although many just send the sample message. Some cell phone apps will even fax the message to a person’s representatives.

Another potential problem is that interest groups, by definition, promote the interests of their members over more general interests. When groups pull in many different or completely opposite directions, compromise becomes challenging and gridlock can result. This phenomenon of multiple competing interest groups is called hyperpluralism. In such a situation, a form of elitism can also develop. Groups with more power and resources are more likely to achieve their goals than groups with smaller memberships or limited funding, putting interest groups on an uneven playing field in the marketplace of ideas.

This lack of resources for smaller groups is intensified by another issue known as the free-rider problem. Groups that push for a collective benefit for a large group inevitably have free riders. The free-rider problem limits the group’s potential because not all those benefiting help pay the bill.

Relationships between interest groups and government representatives develop, deepen, and expand over time, so the inequality of resources and access widens even more.

Iron Triangles and Issue Networks

Iron triangles are the bonds among an agency, a congressional committee, and an interest group. The three entities establish relationships that benefit them all. Bureaucrats benefit by cooperating with congressional members who fund and oversee them. Committee members benefit by listening to interest groups that reward them with campaign donations.

For example, an iron triangle exists to influence policy in favor of those of retirement age. In this relationship, the American Association of Retired Persons (interest group) works with the Subcommittee on Aging (congressional committee) and the Social Security Administration (government agency) to fund, create, and oversee policy that affects seniors.

Issue networks are also collectives with similar goals, but they have come together to support a specific issue and usually do not have the long-term relationships that characterize iron triangles. If and when their issue of common concern is resolved, the networks break up. Issue networks often include a number of different interest groups who share an opinion on the issue at hand but may have strongly differing opinions on other matters. For example, religious interest groups and some civic organizations might have differing views on abortion or same-sex marriage, but they may agree on the importance of health care for children living in poverty and work together to advance that cause.

Exerting Influence

Once an issue has been brought to the surface, the education of both voters and legislators can begin. Interest groups use many different channels to educate the public and legislators about their concerns. With enough public support, interest groups can help draft legislation to support their cause. This process requires ongoing relationships with lawmakers and others in government. To keep up the pressure on legislators to produce the desired result, interest groups mobilize their members and the public to take to the streets in demonstrations or make phone calls or in-person visits to representatives.

Interest groups use a variety of techniques to exert influence. The most common form of activity for those who have access is direct lobbying of legislators. Groups also try to sway public opinion by issuing press releases, writing op-ed articles for newspapers, appearing as experts on television, and purchasing print and TV advertising. They also mobilize their membership to call or write members of Congress or state legislators on pending laws or to swing an election.

Lobbying Legislators

‘The term lobbying came into vogue in the mid-1600s when the anteroom of the British House of Commons became known as “the lobby.” Lobbyists were present at the first session of the U.S. Congress in 1789.

Access to Washington, DC

Lobbyists work to develop relationships through their contacts who have access to government officials. Through these contacts, they monitor legislators’ proposed bills and votes. Lobbyists assess which lawmakers support their cause and which do not. They also help draft bills that their congressional allies introduce and find which lawmakers are undecided and try to bring them over to their side. “Influence peddler” is a derogatory term for a lobbyist, but influencing lawmakers is exactly what lobbyists try to do.

Give and Take

Lobbyists want access to legislators, and Congress members appreciate the information lobbyists can provide. Senators and House members represent the individual constituents living in their districts.

Sometimes so-called special interests actually represent large swaths of a given influential members of Congress, especially those serving on key committees, become interest group targets. Some legislators are especially influential, so lobbyists target them first.

To what degree do lobbyists move legislators on an issue? Little evidence exists to show that lobbyists actually change legislators’ votes. Most findings do not prove lobbyists are successful in “bribing” legislators. Also, lobbyists tend to interact mostly with those members already in favor of the group’s goals.

So the campaign contribution didn’t bring the legislators over to the interest group; the legislator’s position on the issue brought the interest group to him or her.

Researcher Rogan Kersh conducted a two-year study of corporate lobbyists.

“I’m not up here to twist arms and change somebody’s vote,” one lobbyist told him in a Senate anteroom crowded with lobbyists from other firms, “and neither are most of them.” These lobbyists seem more concerned with waiting, gossiping, and rumor trading. A separate study conveyed that lobbyists want information or legislative intelligence as much as the lawmakers do. “If I’m out playing golf with some congressman or I buy a senator lunch, I know I’m not buying a vote,” one lobbyist declared before recent reforms. The lobbyist is simply looking for the most recent views of lawmakers in order to act upon them. Kersh tabulated congressional lobbyists’ legislative activities. A lobbyist attempting to alter a legislator’s position occurred only about 1 percent of the time.

Resources

The types and resources of interest groups affect their ability to influence elections and policy. For example, nonprofit interest organizations fall into two categories based on their tax classification. The 501(c)(3) organizations, such as churches and certain hospitals, receive tax deductions for charitable donations and can influence government, but they cannot lobby government officials or donate to campaigns. By comparison, 501(c)(4) groups, such as certain social welfare organizations, can lobby and campaign, but they can’t spend more than half their expenditures on political issues. Available resources also affect the ability of groups to influence policy. Well-funded groups are usually able to wield more power and to have greater access to government decision makers than groups with fewer resources.

Research and Expertise

Large interest groups have created entire research departments to study their concerns. Mothers Against Drunk Driving wanted to know, “How many lives would be saved if government raised the drinking age from 18 to 21?” The American Bar Association pondered, “What kind of a Supreme Court justice would nominee Clarence Thomas make?” These are the kinds of questions that members of Congress also ask as they contemplate legislative proposals. During the fact-gathering phase of lawmaking, experts from these groups testify before congressional committees to offer their research findings. Since they represent their own interest, researchers and experts from interest groups and think tanks will often focus on the positive aspects of supporting their desired outcomes.

Campaigns and Electioneering

As multiple-term congressional careers have become common, interest groups have developed large arsenals to help or hinder a legislator’s chances at election time. Once new methods-TV ads, polling, direct mail, and marketing determined reelection success, politicians found it increasingly difficult to resist interest groups that had perfected these techniques and that offered greater resources to loyal officials.

A powerful interest group can influence the voting public with an endorsement-a public expression of support. The Fraternal Order of Police can usually speak to a lawmaker’s record on law enforcement legislation and financial support for police departments. The NRA endorses its loyal congressional allies on the cover of the November issue of its magazine, printed uniquely for each district. Groups also rate members of Congress based on their roll call votes, some with a letter grade (A through F), others with a percentage. Americans for Democratic Action and the American Conservative Union, two ideological organizations, rate members after each congressional term. Creating “scorecards” or ratings are also a way interest groups can keep their members engaged or linked to the government process.

Grassroots Lobbying

When an interest group tries to inform, persuade, and mobilize large numbers of people they are grassroots lobbying, which is generally an outsider technique. Originally practiced by the more modest citizens and issue advocacy groups, such as students marching against the war in Vietnam, grassroots techniques are now increasingly used by Washington-based interests to influence officials. Mobilizing opposition or support to legislation can be the primary goal of a grassroots campaign.

In 1982, soon after Republican Senator Bob Dole and Democratic Representative Dan Rostenkowski introduced a measure to withhold income taxes from interest earned on bank accounts and dividends, the American Banking Association went to work encouraging banks to persuade their customers to oppose the measure. The Washington Post called it the “hydrogen bomb of modern day lobbying” Banks used advertisements and posters in branch offices; they also inserted flyers in monthly bank statements mailed out to every customer, telling them to contact their legislators in opposition to the proposed law. Banks generated nearly 22 million constituent communications.

Weeks later the House voted 382-41, and the Senate 94-5, to oppose the previously popular bipartisan proposal.

Framing the Issue

When the debate over the Clean Air Bill of 1990 began, Newsweek asked how automakers could squash legislation that improved fuel efficiency and reduced both air pollution and America’s reliance on foreign oil.

A prominent grassroots consultant reasoned that smaller cars–which would be vital if the act were to be successful–would negatively impact child safety, senior citizens’ comfort, and disabled Americans’ mobility. Opponents of the bill contacted and mobilized senior organizations and disability rights groups to create opposition to these higher standards. What was once viewed as an anti-environment vote soon became a vote that was pro-disabled people and pro-child.

As multiple-term congressional careers have become common, interest groups have developed large arsenals to help or hinder a legislator’s chances at election time. Once new methods-TV ads, polling, direct mail, and marketing determined reelection success, politicians found it increasingly difficult to resist interest groups that had perfected these techniques and that offered greater resources to loyal officials.

Use of Media

Television and telephones, combined with email and social media use, have encouraged grassroots lobbyists and issue advocacy groups. Depending on their tax classification, some groups cannot suggest a TV viewer vote for or against a particular congressperson. So instead they provide some detail on a proposed policy and then tell the voters to contact members of Congress to express their feelings on the issue. Such ads have become backdoor campaigning. They all but say, “Here’s the congressperson’s position. You know what to do on Election Day.”

The restaurant industry responded rapidly to a 1993 legislative idea to remove the tax deduction for business meals. Everyday professionals conducting lunchtime business in restaurants are able to write off the expense at tax time. As Congress debated changing that deduction, special interests acted. The National Restaurant Association (sometimes called “the other NRA”) sponsored a television ad that showed an overworked server-mother: “I’m a waitress and a good one. But I might not have a job much longer. President Clinton’s economic plan cuts business-meal deductibility. That would throw 165,000 people out of work. I need this job.” Opposition to eliminating the tax benefit no longer came from highbrow, lunchtime dealmakers but instead from those wanting to protect hardworking servers, cooks, and dishwashers. At the end of the ad, the server directed concerned viewers to call a toll-free number.

Callers were put through to the corresponding lawmaker’s office with the push of a button. The use of television helped the “other NRA” successfully defeat the bill.

Interest groups increase their chances of success when they reach the masses, but they also target opinion leaders, those who can influence others.

Rather than mobilizing large numbers of people, interest groups and their lobbyists will narrowly target opinion leaders and individuals who know and have connections with lawmakers. This more limited approach to shaping opinion is known as grasstops campaigning. Some lobbyists charge $350 to $500 for getting a community leader to communicate his or her feelings to a legislator in writing or on the phone. They also set up personal meetings between high-profile constituents and members of Congress.

Grasstops lobbying sometimes shifts public opinion in the desired direction; for example, it might cherry-pick selected opinions that create an artificial view, sometimes called “Astroturf.” This deceitful tactic can give the appearance that people are concerned about an issue when, in reality, a powerful interest group is behind the false impression.

Congressional lobbyists sometimes also use grassroots techniques in tandem with their Washington, DC, operations. Once they determine a legislator’s anticipated position, especially if it is undecided, lobbyists can pressure that congressperson by mobilizing constituents in his or her district.

Interest groups can use their website and emails to alert members their help is needed. The interest group will provide messages and talking points so their members can easily create a factual letter to send to their representative.

With email, this technique has become easier, cheaper, and more commonly used than ever before. With the click of a mouse, interest group members can forward a message to a lawmaker to signal where they stand and how they will vote. Such organizing has also become commonplace on social media.

Lobbyists are also developing ways to mine social media for data so they can create highly targeted outreach.

Groups Influencing Policy Outcomes

“Agitate, educate, legislate” were the watchwords of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, an influential anti-alcohol interest group around the turn of the 20th century, neatly summarizing the ways in which many interest groups spread their influence and use it to bring about change. Interest groups have come a long way since their proliferation in the Progressive Era and after a post-World War II boom. ‘They agitated through public demonstrations, like the 1965 Selma, Alabama, march in search of the franchise. They educated the citizenry on the need to preserve the environment. And they have mobilized on health care, firearms, and workplace safety laws.

Many interest groups are now professionalized, well-funded, and well-oiled machines. ‘They provide opportunities for citizen participation in the political arena. Social movements have spawned multiple interest groups seeking to address similar causes. Others oppose each other and duel on the issues as they influence the shaping of policy.

Growth of Interest Groups

Interest groups arose in response to the changes in the United States as the nation developed from a mainly agrarian economy to a manufacturing nation. Immigrants arrived on both coasts, bringing a wide variety of viewpoints into the country. Factory workers banded together for protection against their bosses. War veterans returning from armed conflicts looked to the government for benefits. Women and minorities sought equality, justice, and the right to vote. Congress began taking on new issues, such as regulating railroads, addressing child labor, supporting farmers, and generally passing legislation that would advance the nation. As democracy increased, the masses pushed to have their voices heard.

Broad Interests of Labor Unions

One interest group that represented a broad issue is the American Federation of Labor (AFL), organized in 1886 under the leadership of Samuel Gompers. The AFI’s most useful tool was the labor strike-skilled workers banded together and refused to work until the company met their demands. Labor unions also entered the political arena and pushed for legislation that protected workers against unhealthy and hazardous conditions. Labor unions have been instrumental in achieving new state (and sometimes national) laws addressing the 40-hour workweek, employer-sponsored health care, family and medical leave, an end to child labor, and minimum wages.

Growth of Labor Unions

The power of labor organizations reached new levels in the 1950s. In 1955, the AFL merged with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), a large union composed of steelworkers, miners, and unskilled workers. The AFL-CIO became the leading voice for the working class and is now comprised of 57 smaller unions. Union membership peaked in 1954 with roughly 28 percent of all households belonging to unions. In 1964, the nation’s largest truckers’ union, the Teamsters, signed a freight agreement that protected truckers across the country and increased the union’s power. After a decline in manufacturing started a decline in union membership in the 1960s, union organizers turned to the public sector. Between 1958 and 1978, public sector union membership more than doubled, from about 7.8 million to 15.7 million. Union membership remained high until the early 1980s. Today, about 13 percent of households, or about 7 percent of American workers, belong to organized labor and benefit from union influenced state laws that allow collective bargaining for such public employees as teachers, firefighters, and police.

Business Response to Labor Growth

Businesses soon organized in response to the growing labor movement so they could gain influence for their positions. Manufacturing and railroad firms sent men to influence decisions in Washington. As more and more influential “lobby men” roamed the Capitol, these interests became known as the “third house of Congress.” The number of trade associations, or interest groups made of businesses within a specific industry, grew from about 800 in 1914 to 1,500 in 1923. By 2010, that number had grown to more than 90,000. The National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) was founded in 1895 to advocate for manufacturers’ interests. NAM pushed for the creation of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, which formed in 1912, and its members include many local chambers of commerce in cities across the country, as well as private firms and individuals. Heavily financed, the NAM and the Chamber became deeply involved in politics.

After World War II, civil rights and women’s equality, environmental pollution, and a rising consumer consciousness were the focus of leading social movements. Backing for these causes expanded during the turbulent 1960s as citizens began to rely less on political parties with general platforms and more on interest groups addressing broad issues but working toward very specific goals. Interest groups tied to social movements cannot match the financial resources of the Chamber of Commerce or even unions to lobby policymakers, but they have another tool to help sway opinion—grassroots movements.

Civil Rights

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Urban League were founded in 1909 and 1910, respectively, to seek racial equality and social fairness for African Americans. In the 1950s and 1960s, these groups experienced a dramatic rise in membership, which increased their influence in Washington. NAACP attorneys worked tirelessly to organize black communities to seek legal redress in the courts. In addition to filing cases to challenge unfair laws, the NAACP worked tirelessly to defend wrongly accused African Americans or to assure justice in criminal cases. They still do today. The Urban League worked to increase membership to enhance its influence. Additional civil rights groups surfaced and grew. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) was founded at the University of Chicago and became instrumental in the nonviolent civil disobedience effort to desegregate lunch counters.

Reverend Martin Luther King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(SCIC), an organization of leading black southern clergymen, began a national publishing effort to create public awareness of racist conditions in the South.

‘The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was a leading force in the dangerous Freedom Rides to integrate interstate bus lines and terminals. Whether in the courts, in the streets, or on Capitol Hill, most changes to civil rights policy and legislation, especially the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, resulted from these organizations’ efforts.

Women’s Movement

A growing number of women entered public office in the mid-20th century. Federal laws began to address fair hiring, equal pay, and workplace discrimination. The 1963 Equal Pay Act and the 1964 Civil Rights Act addressed occupational equality but left unsettled equal pay for equal work and a clear definition of sex discrimination. Leading feminist Betty Friedan wrote The Feminine Mystique in 1963 and formed the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966. NOW had 200 chapters by the early 1970s and was joined by the National Women’s Political Caucus and the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (NARAL) to create a coalition for feminist causes. The influence of these groups brought congressional passage of the Equal Rights Amendment (which failed in the state ratification battle) and Title IX (1972), which brought more focus and funding equality to men’s and women’s school athletics. They also fought for the Roe v. Wade (1973) Supreme Court decision that prevented states from outlawing abortion.

Environmental Movement

As activists drew attention to mistreatment of African Americans and women, they also generated a consciousness about the misuse of our environment. Marine biologist Rachel Carson’s best-selling book Silent Spring (1962) criticized the use of insecticides and other pesticides that harmed birds and wildlife. Her title referred to the silence resulting from the death of birds, long the harbingers of springtime cheerfulness. Organizations such as the Sierra Club, the Wilderness Society, and the Audubon Society expanded their goals and quadrupled their membership. In 1963 and 1964, Congress passed the first Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act, respectively, in part through the efforts of the environmental groups. The years of disregard of pollution and chemical dumping into the nation’s waterways reached a crisis point in 1969 when Cleveland’s Cuyahoga River was so inundated with chemicals that it actually caught on fire. This crisis led to even stronger legislation and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970. Also in 1970, Earth Day became an annual event to focus on how Americans could help to preserve the environment. In 1980, environmental interest groups celebrated the creation of the Superfund under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA). The Superfund taxes chemical and petroleum companies and puts the revenue into a trust fund to be used for cleaning up environmental disasters. The first disaster to use Superfund resources was at Love Canal in New York, an abandoned canal project into which a chemical company had dumped 21,000 tons of hazardous chemicals between 1942 and 1953, putting the health of residents in the area at risk.

Consumer Movement

Consumers and their advocates began to demand that manufacturers take responsibility for making products safe. No longer was caveat emptor (“let the buyer beware”) the guiding principle in the exchange of goods and services. In 1962 President Kennedy put forth a Consumers’ Bill of Rights meant to challenge manufacturers and guarantee citizens the rights to product safety, information, and selection. By the end of the decade, Consumers Union established a Washington office, and activists formed the Consumer Federation of America. With new access to sometimes troubling consumer information, the nation’s confidence in major companies dropped from 55 percent in 1966 to 27 percent in 1971.

Ralph Nader emerged as America’s chief consumer advocate. As early as 1959 he published articles in The Nation condemning the auto industry. “It is clear Detroit is designing automobiles for style, cost, performance, and calculated obsolescence,” Nader wrote, “but not for safety.” In 1965 he published Unsafe at Any Speed, an exposé of the industry, especially General Motors (GM) sporty Corvair. To counter Nader’s accusations, GM hired private detectives to tail, discredit, and even blackmail him. When this effort came to light, a congressional committee summoned GM’s president to testify and to apologize to Nader. In 1966, Congress also passed the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, which, among other things, required seat belts in all new cars.

After the financial crisis of 2008-2009, consumer interest groups united under an umbrella organization called Americans for Financial Reform which helped pressure lawmakers to create the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Its responsibilities include regulating debt and collection practices, monitoring mortgage lending, investigating complaints about financial institutions, and obtaining refunds for consumers.

Groups and Members

Interest groups fall into a handful of categories. These consist of institutional (corporate and intergovernmental groups), professional, ideological, member-based, and public interest groups. There is some overlap among these. For example, business groups want to make profits, but they also have a distinct ideology when it comes to taxation and business regulation. Likewise, citizens groups have members who may pay modest dues, but these groups mostly push for laws that benefit society at large.

Institutional Groups

Institutional groups break down into several different categories, including intergovernmental groups, professional associations, and corporations. The U.S. system of redistributing federal revenues through the state governments encourages government-associated interest groups. Governors, mayors, and members of state legislatures are all interested in receiving funding from Washington. The federal grants system and marble cake federalism increase state, county, and city interest in national policy. Governments and their employees – police, firefighters, EMTs, sanitation workers, and others have a keen interest in government rules and regulations that affect their jobs and funding that impacts their salaries. This interest has created intergovernmental lobby, which includes the National Governors Association, the National League of Cities, and the U.S. Conference of Mayors, all of which have offices in the nation’s capital.

Unlike labor unions that might represent tradesmen like pipefitters or carpenters, professional associations typically represent white-collar professions. Examples include the American Medical Association (AMA) and the American Bar Association (ABA). They are concerned with business success and the laws and practices that guide their trade. The AMA endorsed the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The ABA rates judicial nominees and testifies before Congress about proposed crime bills. Police and teachers’ unions, such as the Fraternal Order of Police or the National Education Association, are often associated with the labor force, but in many ways, they fall into this category.

The Business Roundtable, formed in 1973, represents firms that account for nearly half of the nation’s gross domestic product. During this time, new conservative think tanks – research institutions, often with specific ideological goals-emerged and old ones revived. The American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, among other policy institutes, countered the ideas and policy coming from liberal think tanks and progressive foundations.

Some think tanks are associated with universities, even though their funding comes entirely from corporations, philanthropic foundations, and private individuals. For example, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in Virginia was founded to promote free market ideas and solutions in higher education with the backing of billionaire Libertarian Charles Koch and other free market proponents. As writer John Judis explains, in 1971, only 175 businesses registered lobbyists in Washington. By 1982, there were 2,445 companies that had paid lobbyists. The number of corporate offices in the capital jumped from 50 in 1961 to 500 in 1978 and to 1,300 by 1986. By 1978, 1,800 trade associations were headquartered in the nation’s capital. Today, Washington has an army of lawyers and public relations experts whose job it is to represent corporate interests and lobby the government for their corporate clients.

Professional Organizations

Most groups have a defined membership and member fees, typically ranging from $15 to $40 annually. (Corporate and white-collar associations typically charge much higher fees.) When groups seek to change or protect a law, they represent their members and even nonmembers who have not joined. For example, there are many more African Americans who approve of the NAACP’s goals and support their actions than there are actual, dues-paying NAACP members. There are more gun advocates than members of the National Rifle Association (NRA). These nonmembers choose not to bear the participation costs of time and fees but do benefit from the associated groups’ efforts—the free rider problem.

To encourage membership, interest groups offer incentives. Purposive incentives are those that give the joiner some philosophical satisfaction. They realize their money will contribute to some worthy cause. If they donate to an organization addressing climate change, for example, they might feel gratified that their contribution will help future generations. Solidary incentives are those that allow people of like mind to gather on occasion. Such gatherings include monthly organizational meetings and citizen actions. Many groups offer material incentives, such as travel discounts, subscriptions to magazines or newsletters, or complimentary items such as bags, caps, or jackets.

One study found that the average interest group member’s annual income is $17,000 higher than the national average and that 43 percent of interest group members have advanced degrees, suggesting that interest group membership has an upper-class bias. Though annual membership fees in most interest groups are modest, critics argue that the trend results in policies that favor the higher socioeconomic classes. As opposed to special interest groups, public interest groups are geared to improve life or government for the masses. Fully 30 percent of such groups have formed since 1975, and they constitute about one-fifth of all groups represented in Washington.

In 1970, Republican John Gardner, who was President Lyndon Johnson’s Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, took what he called the biggest gamble of his career to create Common Cause. “Everybody’s organized but the people,” Gardner declared when he put out the call to recruit members to build “a true citizens’ lobby.” Within six months Common Cause had more than 100,000 members. The antiwar movement and the post-Watergate reform mindset contributed to the group’s early popularity. Common Cause’s accomplishments include the Twenty-sixth Amendment to grant voting rights to those 18 and over, campaign finance laws, transparent government, and other voting reforms. More recently, the group pushed for the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform (McCain-Feingold) Act and the 2007 lobbying regulations in the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, which called for public disclosure of lobbying activities and limits gifts for Congress members. Today, Common Cause has nearly 400,000 members and 38 state offices.

With money from a legal settlement with General Motors, Ralph Nader joined with other consumer advocates to create Public Citizen in 1971. He hired bright, aggressive lawyers who came to be known as Nader’s Raiders. In 1974, U.S. News and World Report ranked Nader as the fourth-most influential man in America. Carrying out ideals similar to those that Nader had emphasized in the 1960s—consumer rights and open government—Public Citizen tries to ensure that all citizens are represented in the halls of power. It fights against undemocratic trade agreements and provides a “countervailing force to corporate power.” Nader went on to create other watchdog organizations, such as the Center for Responsive Law and Congress Watch, to address the concerns of ordinary citizens who don’t have the resources to organize and lobby government.

Single-Issue and Ideological Groups

Some interest groups form to address a narrow area of concern. Two single-issue groups—focused on just one topic—of note are the National Rifle Association (NRA) and the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP).

The National Rifle Association (NRA) is the “single-issue” group most associated with narrow interest lobbying. The NRA has gone from post-Civil War marksmen’s club to pro-gun Washington powerhouse, especially in the last 30 years under the leadership of lobbyist Wayne LaPierre. Its original charter was to improve the marksmanship of military soldiers. After a 1968 gun control and crime law, the NRA appealed to sportsmen and Second Amendment advocates. Its revised 1977 charter states that the purpose of NRA is “generally to encourage the lawful ownership and use of small arms by citizens of good repute.” In 2001 Fortune magazine named the NRA the most powerful lobby in America. The NRA appeals to law enforcement officers and outdoorsmen with insurance policies, discounts, and its magazine American Rifleman. The group holds periodic local dinners for “Friends of the NRA” to raise money. The annual convention provides a chance for gun enthusiasts to mingle and view the newest firearms, and attendance reaches beyond 50,000 gun enthusiasts.

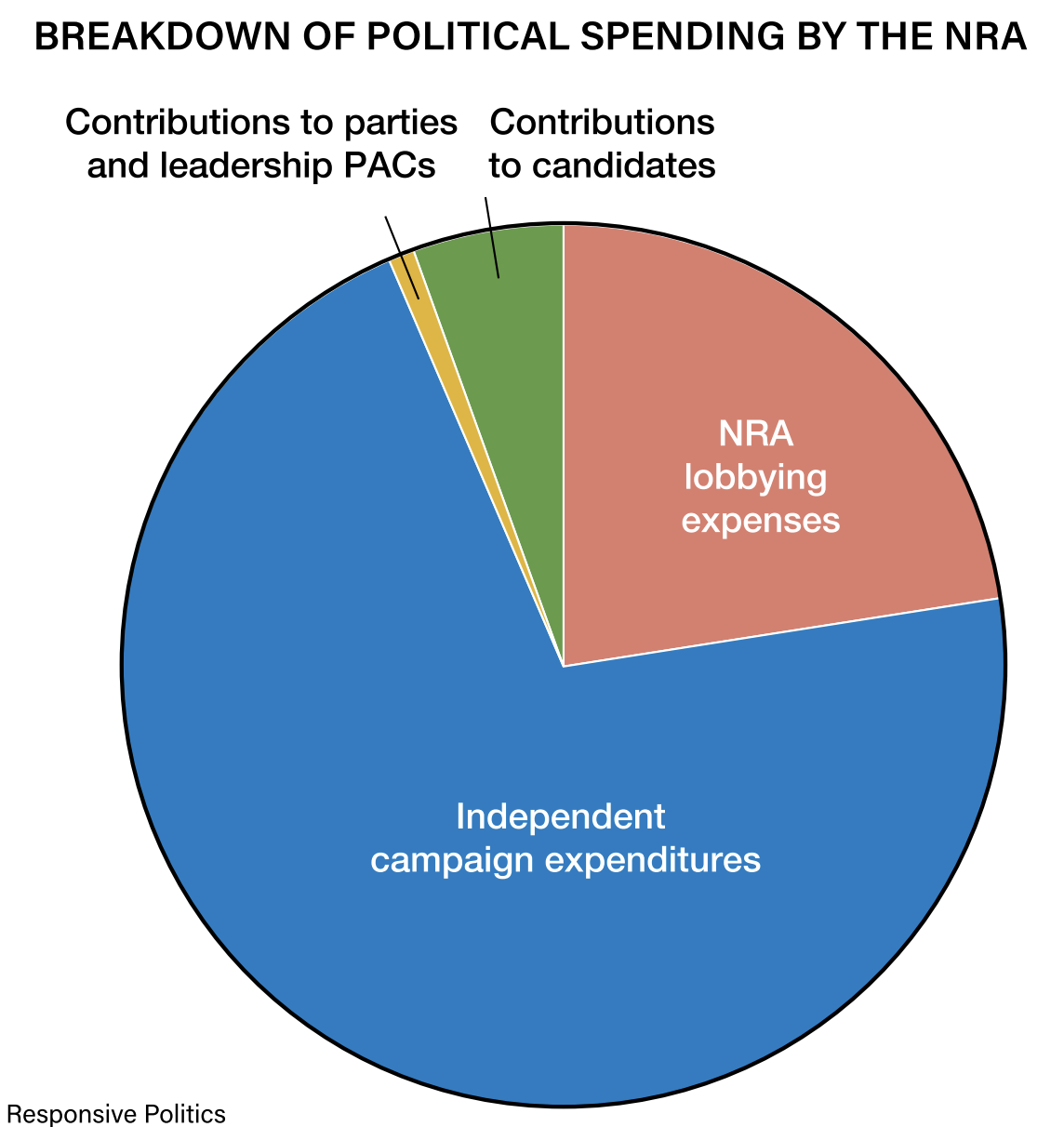

The NRA endorses candidates from both major political parties but heavily favors Republicans. From 1978 to 2000 the organization spent more than $26 million in elections; $22.5 million went to GOP candidates and $4.3 went to Democrats.

The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) has the largest membership of any interest group in the nation. AARP has twice the membership of the AFL-CIO, its own zip code in Washington, and its own registered in-house lobbyists. Its magazine has the largest circulation of any monthly publication in the country. People age 50 and over can join for $16 per year. The organization’s main concerns are members’ health, financial stability and livelihood, and the Social Security system. “AARP seeks to attract a membership as diverse as America itself,” its website claims. With such a large, high voter-turnout membership, elected officials tend to pay close attention to AARP.

You have already read about a number of ideological groups—interest groups formed around a political ideology. On the liberal side of the ideology spectrum are groups such as the NAACP and NOW. On the other end of the spectrum, conservative ideological interest groups include the Christian Coalition and the

National Taxpayers Union.

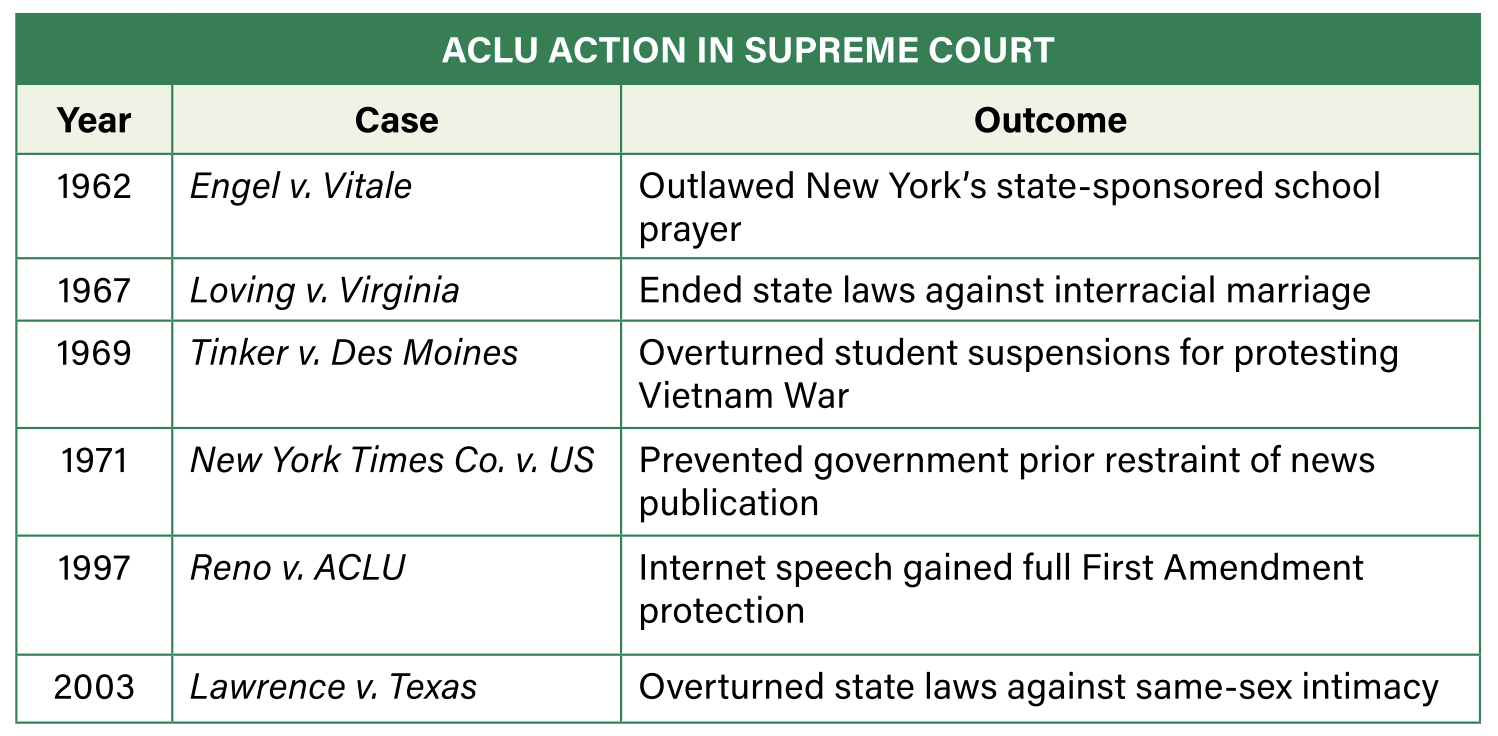

One of the more active groups today is the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) which formed after World War I to counteract the government’s authoritarian interpretation of the First Amendment. At that time, the federal government deported radicals and threw dissenters of the war and the military draft in jail. Guaranteeing free expression became the ACLU’s central mission.

In 1925, the organization went up against Tennessee state law to defend John Scopes’ right to teach evolution in a public school. Over the following decades, the ACLU opened state affiliates and took on other civil liberties violations. It remains very active, serving as a watchdog for free speech, fair trials, and racial justice. The ACLU has about half a million members, about 200 attorneys, a presence on Capitol Hill, and chapters in all 50 states.

Interest Group Pressure on Political Parties

Political parties and interest groups are both linkage institutions, creating connections between people and government. Political parties and interest groups also have connections between them. Some interest groups align with political parties that share their ideology and goals by endorsing candidates in that party and encouraging their membership to vote for those candidates.

However, interest groups can also exert pressure on political parties in areas of disagreement, and the result can be an official party ideology shift in the direction of the interest group pressure.

Republican Party’s Pull to the Right

Several examples in recent history show the power of interest groups to influence policy positions of political parties. For example, as early as 1940, the Republican Party declared in its platform, “We favor submission by Congress to the States of an amendment to the Constitution providing for equal rights for men and women.” With that statement, Republicans were the first party to endorse the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) after Congress proposed submitting it to the states for their ratification in 1972. By 1980, however, the Republican platform expressed a different stance to the ERA: “We acknowledge the legitimate efforts of those who support or oppose ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment.”

What happened during the eight years between those statements to shift the Republican position?

Phyllis Schlafly (1924-2016) was a lifelong Republican, playing an active role in the party and even running for office. She founded a conservative interest group, now called the Eagle Forum, in 1972, but refocused her energy on stopping the Equal Rights Amendment by founding the interest group STOP ERA (STOP stands for “Stop Taking Our Privileges”). By this time the ERA had won overwhelming support in Congress and ratification of 30 of the required 38 states. Schlafly’s organization took the position that the ERA would disadvantage women—that it would deprive them of certain spousal rights, require them to serve in the armed forces and in combat, force them to use unisex bathrooms—and eventually lead to same-sex marriage. Against the backdrop of the Supreme Court’s 1962 ban on school prayer in Engel v. Vitale and the legalization of abortion in Roe v. Wade in 1973, women from a variety of backgrounds, especially conservative and Christian, feared that their traditional values were under attack, and they feared the consequences of the ERA that Schlafly predicted.

The anti-ERA movement gained so much strength that the Republican Party could not ignore its influence, and it withdrew its support for the ERA from its platform. STOP ERA and other anti-ERA interest groups, including Concerned Women for America, Women for Constitutional Government, the John Birch Society, and Daughters of the American Revolution, carried out well-organized efforts and were successful in halting the ratification of the amendment and at the same time in pulling the Republican Party toward more conservative policy positions.

In a similar way, after President Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, the Tea Party (“Tea” stands for “Taxed Enough Already”) movement appeared on the scene to combat it and other government spending considered to be handouts to undeserving people. A number of interest groups arose as a result of this movement, and they helped elect conservative replacements for more moderate Republicans at every level of government. Once again, the Republican Party was pulled to the right as a result of pressure from interest groups.

Democratic Party’s Push to the Left

The Democratic Party has experienced a similar shift in policy positions. Until the 20th century, it was more conservative than the Republican Party (the party of Abraham Lincoln) and was opposed to civil rights. However, during the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in the 1930s and 1940s, African Americans aligned with the Democrats. During the administration of Lyndon Johnson in the 1960s, powerful interest groups such as NAACP exerted pressure for progress in civil rights legislation, and the Democratic Party welcomed more African American and other minority voters, as well those favoring the ERA and opposing war. Its policy positions became more liberal in the party’s shift to the left.

Other interest groups have also greatly influenced the Democratic Party. In 1984, the National Organization for Women (NOW) made its first-ever presidential endorsement when it endorsed Democratic candidate Walter Mondale, and the Democratic Party made history by nominating Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, the first woman to be nominated for vice president by a major party. In 1985, EMILY’s List was founded to help Democratic women to office. (EMILY stands for “Early Money Is Like Yeast,” referring to the importance of securing donations early in a candidate’s campaign in order to ensure donations later as well, to help a campaign rise as yeast makes dough rise.) Its first victory was the election of Senator Barbara Mikulski of Maryland, who became the longest-serving woman in the history of Congress. EMILY’s List has gone on to help many Democratic women, including women of color and gay women, get elected. These strong associations between women’s interest groups and the Democratic Party influenced the party’s stand on women’s issues.

The Sierra Club, a large environmental interest group, also carries influence with the Democratic Party. Many of its resources go to lobbying for environmental protection, and nearly all of its super PAC money goes to Democratic candidates. Super PACs can make unlimited independent contributions as long as the committee is not directly advocating for a candidate.

Ethics and Reform

Lobbyists work for many different interests. The Veterans of Foreign Wars seeks to assist military veterans. The Red Cross, United Way, and countless public universities across the land employ lobbyists to seek funding and support. Yet the increased number of firms that have employed high-paid consultants to influence Congress and the increased role of PAC money in election campaigns have given lobbyists and special interests a mainly negative public reputation.

The salaries for successful lobbyists typically outstrip those of the public officials they seek to influence. Members of Congress and their staffs can triple their salaries if they leave Capitol Hill to become lobbyists. This situation has created an era in which careers on K Street—the noted Washington street that hosts a number of interest group headquarters or lobbying offices—are more attractive to many than careers in public service. Still, old and recent bribery cases, lapses of ethics, and conflicts of interest have led to strong efforts at reform.

Scandals

Bribery in Congress, of course, predates formal interest groups. In the 1860s Credit Mobilier scandal, a holding company sold low-priced shares of railroad stock to members of Congress in return for favorable votes on pro-Union Pacific Railroad legislation. A century ago, Cosmopolitan magazine ran a series entitled “Treason in the Senate” that exposed nine senators for bribery. In the late 1940s, the “5 percenters,” federal officials who offered government favors or contracts in exchange for a 5 percent cut, went to prison. Over the years, Congress has had to pass several laws to curb influence and create greater transparency.

The high-profile cases of congressmen Randall “Duke” Cunningham and lobbyist Jack Abramoff created headlines in 2006 that exposed lawlessness taking place inside the lawmaking process and the effects of elitism. Cunningham, a San Diego Republican representative, took roughly $2.4 million in bribes to direct Pentagon military defense purchases to a particular defense contractor. That contractor, a California organization with more power, resources, and influence than its competitors, supplied Cunningham with lavish gifts and favors such as cash, a Rolls-Royce, antique furniture, and access to prostitutes. He was convicted in 2006.

A more publicized scandal engulfed lobbyist Jack Abramoff, whose client base included several Native American casinos. He was known to trade favors—fancy dinners, golf trips to Scotland, lavish campaign contributions—for legislation. He pled guilty in January 2006 to defrauding four wealthy tribes and other clients of nearly $25 million as well as evading $1.7 million in taxes, and he went to jail.

Recent Reform

Congress responded with the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act (HLOGA) in 2007. New rules banned all gifts to members of Congress or their staff from registered lobbyists or their clients. It also banned members from flying on corporate jets in most circumstances and restricted travel paid for by outside groups. The 2007 law also outlawed lobbyists from buying meals, gifts, and most trips for congressional staffers. Lobbyists must now file expense reports quarterly instead of twice a year. The new law also requires members to report the details of any bundling raising large sums from multiple donors for a candidate. Lobbyists who bundle now have to report it if the combined funds equal more than $15,000 in any six-month period. Also, for the first time ever, lobbyists who break ethics rules will face civil and criminal penalties of up to $200,000 in fines and five years in prison.

Revolving Door

However, the HLOGA had loopholes that have been repeatedly exploited. One relates to the matter of the revolving door—the movement from the job of legislator to a job within an industry affected by the laws or regulations. Many officials leave their jobs on Capitol Hill or in the executive branch to lobby the government they departed. Some members of Congress take these positions after losing an election. Others do so because they can make more money by leaving government and working in the private sector. These former lawmakers already have influential relationships with members of Congress.

A Public Citizen study found that half the senators and 42 percent of House members who left office between 1998 and 2004 became lobbyists. Another study found that 3,600 former congressional aides had passed through the revolving door. The Center for Responsive Politics identified 310 former Bush and 283 Clinton appointees as lobbyists working in the capital. As of late 2019, 356 former members of Congress serve as registered lobbyists.

Interest groups by definition promote the interests of their members over more general interests. When groups pull in many different or completely opposite directions, compromise becomes impossible and gridlock can result. This phenomenon is called hyperpluralism. In such a situation, a form of elitism can also develop. Groups with more power and resources are more likely to achieve their goals than groups with smaller memberships or more limited funding, putting interest groups on an uneven footing in the “marketplace of ideas.”

The challenges created by powerful interest groups have led some critics to wish to silence their voices. However, these critics need look no further than the First Amendment to understand why this cannot be done. Interest groups are legal and constitutional because the amendment protects free speech, free association, and the right to petition the government. In response to escalating lobbying efforts over the years, however, Congress began in 1946 to require lobbyists to register with the House or Senate. The Supreme Court upheld lobbyists’ registration requirements but also declared in United States v. Harriss (1954) that the First Amendment ensures anyone or any group the right to lobby.