Challenges:

branches of government

taxes

currency

military/army

Articles of Confederation:

Identify weaknesses in the Articles of Confederation and their effects on the ability to govern.

Need to Know:

constitutional convention

Shay’s Rebellion

Great Compromise

Virginia Plan

New Jersey Plan

bicameral legislator

It took five drafts of the Articles of Confederation (formally known as the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union) before delegates agreed on the sixth version and sent it to the states for approval in 1777. The colonies had recently declared independence, and the Revolutionary War was underway, presenting an urgent need for a formal government. Disagreements over land charters between states slowed ratification of the Articles. Thomas Jefferson finally persuaded the thirteenth state to ratify in 1781.

The difficulties in ratifying the Articles of Confederation foreshadowed governing problems. A lack of national unity and a struggle for power were only two of many challenges the United States would face under the Articles.

The Articles of Confederation

The Continental Congress created a committee of 13 men to draft the Articles of Confederation, the document that laid out the first form of government for the new nation. The Articles redefined the former colonies as states and loosely united them as a confederation or alliance under one governing authority. Each state wrote its own constitution, many of which were pointedly in response to the injustices the colonists had experienced under British rule. The state constitutions shared other features as well: they provided for different branches of government, they protected individual freedoms, and they affirmed that the ruling power came from the people.

John Dickinson wrote the 1776 draft of the Articles, which after revisions was submitted to the states for approval. This document defined “the firm league of friendship” that existed among the states, which had delegated a few powers to the national government.

The question of how to apportion states representation in the newly designed Confederation Congress was beset with controversy. Some leaders recognized the merits of giving greater representation to the more populated states, something the Virginia delegation advocated. Leaders from smaller states opposed representation based on population. After a furious debate, the authors of the Articles created an equal representation system – each state received one vote in the new

Confederation Congress.

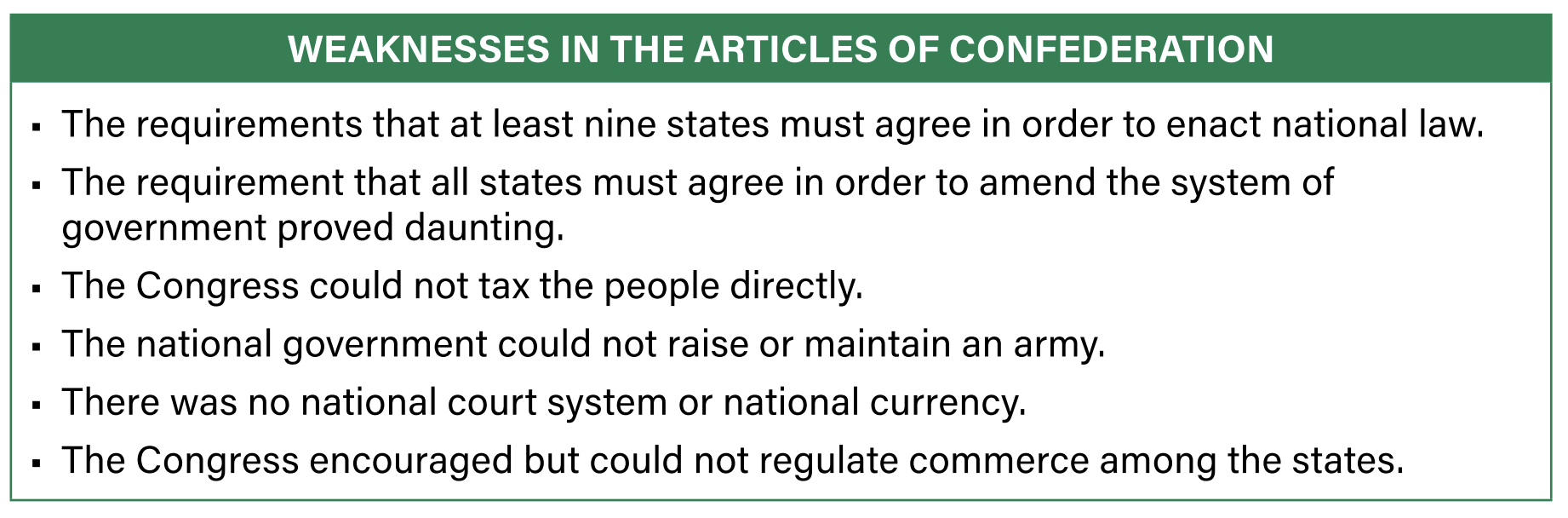

The Confederation Congress met in New York. States appointed delegations of up to seven men who voted as a unit. National legislation required the votes of at least nine states. A unanimous vote was required to alter or amend the Articles of Confederation themselves or to alter the format of government. The Articles entitled the Congress to engage in international diplomacy, declare war, and acquire territory. They provided protection of religion and speech.

They provided for extradition – the return of criminal fugitives and runaway slaves back to states they had fled. The Articles encouraged a free flow of commerce among the states. They required that states provide a public, fair government and that Congress could sit as a court in disputes between states.

An Ineffective Confederation

The people of the confederation feared a strong national government, having just suffered the abuses of the British crown as colonists. Yet, they wanted a structure to keep them organized and united, especially for the economic success of all. Many Americans felt the best way to achieve this outcome was to tip the power in favor of states over a national authority. States, which many felt a sense of loyalty to above the nation, had a wide variety of characteristics and needs to be accommodated by this new form of government.

The Articles of Confederation provided a weak system for the new United States and prevented leaders from making much domestic progress. The system had rendered the Confederation Congress ineffective. In fact, the stagnation and a degree of anarchy threatened the health of the nation.

The following chart summarizes some of the weaknesses.

Financial Problems and Inability to Tax

The national government under the Articles lacked the power to mandate taxes, forcing it to rely on voluntary assistance from states to meet its financial needs. States did not lack the funds to pay those taxes, but they did harbor disdain for taxes imposed by a more remote authority after having fought a long war over the issue. One Massachusetts legislator wrote his member of Congress, stating citizens “seem to think that independency being obtained, their liberty is secured without paying the cost, or bestowing any more care upon it.” Without taxes, the new government couldn’t pay foreign creditors and lost foreign nations faith and potential loans.

For six years, the Confederation Congress and the infant country wrestled with how it would pay for the independence it had earned while remaining skeptical of giving too much taxing power to its national government. By January 1782, 11 states had approved a resolution to empower Congress to adopt a 5 percent import tax. But Rhode Island’s unanimous rejection of the bill and Virginia’s less-united “no” vote killed the plan.

In 1783, Virginia Congressman James Madison tried again with a tax formula based on state populations (slaves would count as three-fifths a person). For four years, it had the popularity of a strong majority but not the unanimous vote necessary. Many already feared Congress’s power to make war and did not want to bestow it with the power to tax. After the final defeat of the 1783 tax proposal, no one believed that the states would ever adopt serious tax reform under the Confederation.

Shays’ Rebellion

The lack of a centralized military power and readiness to respond to a violent uprising became the closing argument of the need for a strong central government. In western Massachusetts in 1786, a large group of impoverished farmers, including many Revolutionary War veterans, lost their farms to mortgage foreclosures and their failure to pay higher than average state taxes.

They organized, disrupted government, and obstructed court claims. The insurgents demanded the government ease financial pressures by printing more money, lowering taxes, and suspending mortgages. In early 1787, Daniel Shays, a former captain in the Continental army, led a band of violent insurgents to the federal arsenal in Springfield. Local authorities had difficulty raising a militia and only did so from private funds. Massachusetts general William Shepard blocked Shays’ army. Artillery fire after a standoff killed four and wounded about 20 of Shays’ men. The protesting squads retreated, but additional face-offs, skirmishes, and sporadic guerrilla warfare followed. By February, the rebellion was largely suppressed.

Even if quashed, Shays’ Rebellion demonstrated to the nation’s leaders that the lack of a centralized military power posed a threat to America’s security.

A small group convened in Annapolis, Maryland, to discuss the economic drawbacks of the Confederation and how to preserve order. This convention addressed trade and the untapped economic potential of the new United States. Nothing was finalized, except to secure a recommendation for Congress to call a more comprehensive convention.

Congress did so: It was to meet in Philadelphia in May 1787. By then few Americans viewed the Articles of Confederation as sufficient. John Adams, who was serving in Congress, argued that a man’s “country” was still his state and, for his Massachusetts delegation, the Congress was “Our embassy.” There was little sense of national unity.

Ratification of the U.S. Constitution

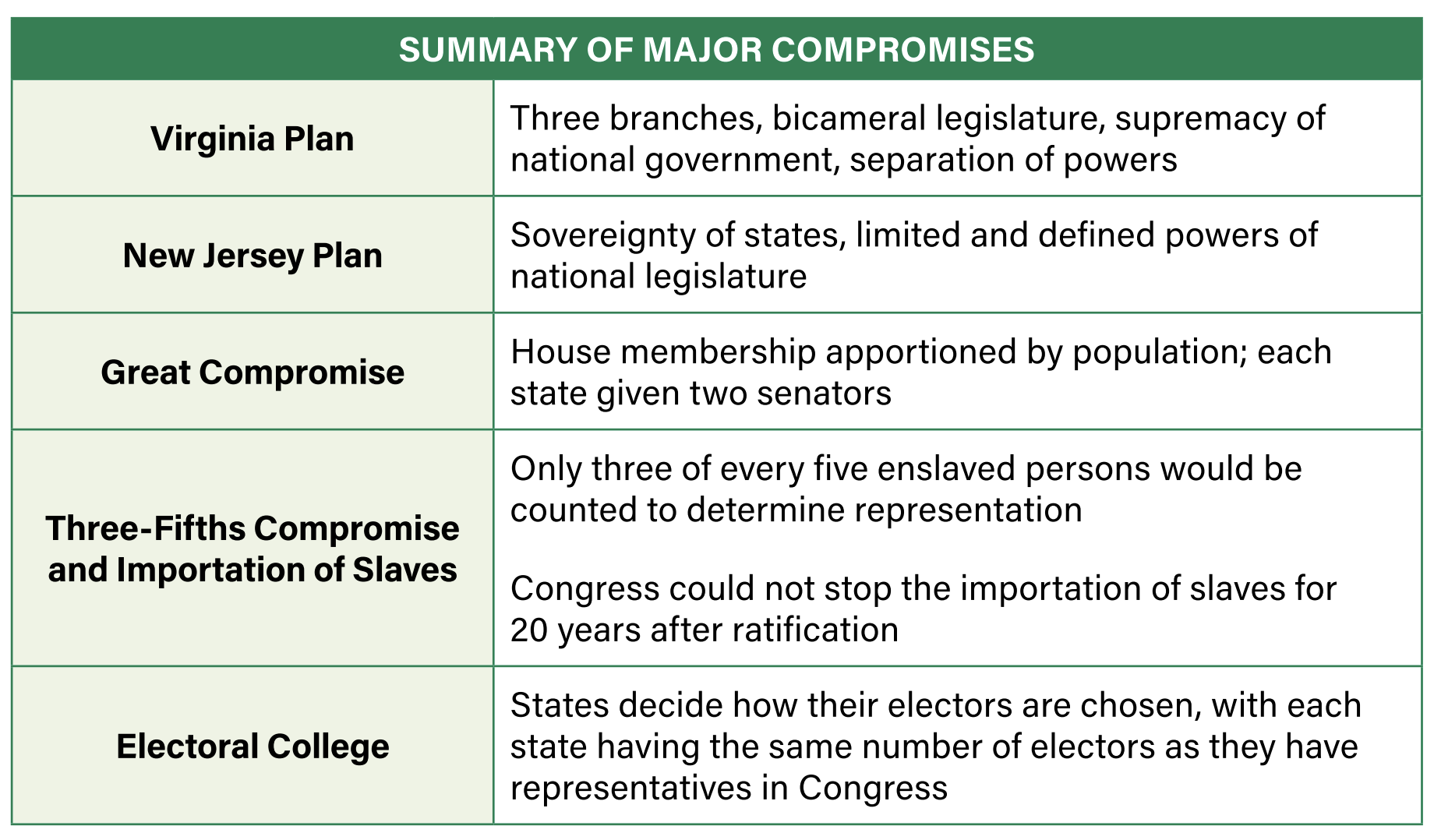

The Constitutional Convention’s quest for an improved government required countless compromises. The 55 delegates from the states had the difficult task of finding common ground for all of these interests under one governing body. In addition to uniting these diverse groups within the new nation, the delegates demonstrated a willingness to compromise to design a government that could meet the needs of the nation in years to come. In fact, the Constitution is a “bundle of compromises.”

Competing Interests

Sharp differences arose between groups in the new nation. Each group wanted what they perceived as fair representation as the delegates at the Constitutional Convention hammered out a plan. They also had differing views on slavery, the nature of the executive, and the relationship of the states to the national government.

Constitutional Compromises

During the summer of 1787, intense negotiations at the convention produced a number of compromises that resulted in a lasting document of governance.

Differing Plans

Different delegates presented different plans at the convention. Virginia Governor Edmund Randolph proposed the Virginia Plan which called for a three-branch system with a national executive, a judiciary, and a bicameral—or two-house—legislature. The people would elect the lower house whose members would, in turn, elect the members of the upper house. This plan also made the national government supreme over the states and set clear limits for each of the branches. The comprehensive Virginia Plan, authored largely by James Madison, created the blueprint or first draft of the Constitution.

Small states feared the overwhelming representation of larger states and supported the plan of New Jersey governor William Paterson. The New Jersey Plan assured states their sovereignty through a national government with limited and defined powers. This plan also had no national court system and each state would have one vote in a legislative body.

The Great Compromise

Representation had been the frustration of the colonists since they began seeking independence. The more populated states believed they deserved a stronger voice in making national policy decisions.

“The smaller states sought to retain an equal footing.” The matter was referred to the Grand Committee made up of one delegate from each of the 12 states present (Rhode Island did not attend). When Roger Sherman of Connecticut joined the committee, taking the place of Oliver Ellsworth who became ill, he took the lead in forging a compromise that became known as the Great Compromise (or the Connecticut Compromise). Sherman’s proposal created a two-house Congress composed of a House of Representatives and a Senate. His plan satisfied both those wanting population as the criteria for awarding seats in a legislature, because House seats would be awarded based on population, and those wanting equal representation, because the Senate would receive two senators from each state, regardless of the state’s size.

Slavery and the Three-Fifths Compromise

The House’s design required another compromise. Delegates from non-slave states questioned how enslaved people would be counted in determining representation. Since enslaved people did not have the right to vote, others who were able to vote in slave states would have more sway than voters in non-slave states if enslaved people were counted in the population. Roger Sherman once more put forward a compromise, this time with Pennsylvania delegate James Wilson. Using the formula from Madison’s proposed-but-failed tax bill, they introduced and the convention accepted the Three-Fifths Compromise—the northern and southern delegates agreed to count only three of every five enslaved persons to determine representation in the House for those states with slaves.

Other compromises would be necessary during the summer-long convention in Philadelphia. For example, delegates debated whether or not the United States needed a president or chief executive and how to elect such an officer. Some argued Congress should elect the president. Others argued for the states to choose the president, and some thought the people themselves should directly elect the president. The Electoral College was the compromise solution.

Under this plan, states could decide how their electors would be chosen. Each state would have the same number of electors that they had representatives in Congress, and the people would vote for the electors. Having electors rather than the citizenry choose the president represents one way in which the elite model of democracy helps shape government today.

Two other issues regarding slavery were addressed: whether the federal government could regulate slavery and whether non-slave states would be required to extradite escaped slaves. Delegates resolved the first matter by prohibiting Congress from stopping the international slave trade for twenty years after ratification of the Constitution (which it did. They also debated how to handle slave insurrections, or runaways. They resolved the second debate with an extradition clause that addressed how states should handle runaway enslaved persons and fugitive criminals.