Need to Know:

linkage institution: political parties, interest groups, elections, election campaigns, media

Political Parties:

mobilize voters

party platform

candidate recruitment

fundraising

campaign organizations

party leadership

Changes in Political Parties:

interactions with candidates

changing platforms

campaign finance

communication trends

Political parties are organized groups of people with similar political ideologies and goals. They work to elect candidates to public office who will represent those ideologies and accomplish those goals. Political parties developed in the aftermath of the American Revolution because of diverging opinions about the structure and power of the new government. In his farewell address, George Washington criticized political parties as being driven by self-interest rather than by a desire to enhance the well-being of the new nation. Other founders agreed that political parties could be a damaging force to the nation.

However, when like-minded people desire certain policy changes in a democratic society, existing political parties take action or new parties form. Organized parties provide important opportunities and link people to government.

Linking People to Government

Political parties are one of several entities that serve as linkage institutions-channels that connect people with the government -keeping people informed and trying to shape public opinion and policy. Other linkage institutions are interest groups, elections, and the media.

Political parties connect with and persuade voters, and sometimes the persuasion goes the other way as well: Enough voters can change a party’s overall views. Parties engage in varied activities to mobilize their members, to gain new ones, and to get them to vote on election day. The parties are organized into a somewhat hierarchical institution that have written bylaws, a platform on the issues, goals, and a funding system.

Impact on Voters and Policy

Political parties can exert a great influence on voters. They can both shape and reflect voters’ political ideologies. They play a large role in deciding which candidates will run for office, and they exercise significant control over the drawing of legislative districts, a process that can tilt the likelihood of election victory to the party in power, especially in gerrymandered districts.

Republican or Democratic Party “members” could be lifelong party loyalists, just common voters who tend to side with the party on election day, or somewhere in between. Parties have no restrictions on who can become members. People who refer to themselves as Republicans or Democrats, or who regularly vote that way, are considered party members. More active and dedicated members volunteer for the party, make donations, or run for office.

Parties also engage voters in the routines of public life. For example, more active, local party members may hold monthly meetings, make calls to get voters to the polls, volunteer at the polling places on election day, and gather at a neighborhood restaurant to watch the election results come in. Through these activities, the party is connecting with the electorate and members are connecting with other members, building social and political bonds. These activities link the voters to government and provide access to participation.

Mobilization and Education of Voters

Political parties always look to add rank-and-file members, because winning elections is essential to implementing party policy. Local activists register and mobilize voters as they recruit more members-not just the party regulars but those who are on the fence about which side to take. They contact citizens via mail, phone, email, text message, social media, or at the door. Volunteers operate phone banks and make personal phone calls to citizens. Parties also use robocalls-prerecorded phone messages delivered automatically to large numbers of people to remind people to vote for their candidates and to discourage voting for opposing candidates.

Political parties also hold voter registration drives. As elections draw near, small armies of volunteers canvass neighborhoods, walking door to door spreading the party philosophy, handing out printed literature and convincing citizens to vote for their causes and candidates. What is sometimes termed a “shoe-leather campaign” can gain more votes than a less personalized email blast. On election day, volunteers will even drive people to the polls.

At the national, state, and local levels, parties educate their members on key issues and candidates. Parties also inform members of government activity, both good and bad. They may tout accomplishments of supported local officeholders or criticize those in the opposing party to stop unwanted policies.

Parties provide extensive training to candidates in how to run an effective campaign. They also train volunteers in the process of building party membership, getting out the vote, and interacting with elected officials. This education effort goes both ways. To make sure their officeholders make decisions that reflect the voters’ desires, parties conduct opinion surveys on the issues and share results with officeholders and candidates to educate them on party members’ positions.

Creation of Party Platforms

A party expresses its primary ideology in its platform -a written list of beliefs and political goals. In drafting a platform, national party leaders try to take into account the views of millions of voters. These views are reflected in each party’s platform.

The modern Republican Party supports a conservative doctrine. Republicans for decades have advocated for a strong national defense, a reduction of government spending, and limited regulations on businesses. However, in 2020 for unspecified reasons, Republicans chose not to issue an updated platform.

The Democratic Party, on the other hand, support aggressive efforts for minority rights and stronger protections for the environment. Democrats also desire more government services for the citizenry and programs to solve public problems.

National Conventions

Gathering of party leaders established a tradition and necessary function- the national convention. Democrats and Republicans arrive at their respective conventions with drafts of their platforms constructed weeks earlier. Each party has an official platform committee appointed by its leadership. As multiple presidential candidates within each party compete for the nomination, party leaders address the different factions’ concerns. Once the party has a nominee, the runners-up maintain strong input on the platform.

In 2016, for example, second-place Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders of Vermont was allowed to name five of the 15 members of the platform-writing committee; the winning presidential nominee, Hillary Clinton, got to name six members; and the party chair appointed the others. Because of Sanders’s influence, the final platform included a desire for a $15 minimum wage. Giving a runner-up this much influence on the document is both principled and practical. Sanders received votes from party members in the primary election. The party wants them represented and needs those members to vote in the general election.

As official statements of position, platforms matter to party leaders. However, most citizens do not follow the platform fight at the convention or read the final draft once it is available on the Internet. Nuances in platform language do not affect too many voters, but they could signal the beginning of an evolution in the party that may take a few election cycles to appear.

Candidate Recruitment

Parties are always looking for talented candidates to run for office, especially those with their own financial resources or a strong, established following. For instance, after World War II, both parties at the national level sought to recruit General Dwight Eisenhower to run for president. Because he was a career soldier, mostly apolitical, and widely popular for his role in the victory over the Axis powers, a “Draft Eisenhower” movement started among some Democrats for the 1948 election. The Republicans succeeded in making him their candidate in 1952. Party officials have recruited other presidential candidates, but typically there’s no shortage of experienced and well-funded contenders who have their eye on the presidency.

The party apparatus will look aggressively for candidates to run for the state legislature or for the U.S. Congress, especially in “safe” districts, those where a party consistently wins by more than 55 percent. Both major parties have recruiting programs that operate from Washington, DC. These recruiters mark swing districts and swing states (see Topic 5.8) on maps and keep an eye on rising talent in those areas. Ideally, they find energetic, telegenic, and scandal-free candidates with good resumes and a talent for fundraising, especially in the move toward candidate-centered elections.

National officials from Washington will sometimes call or visit these prospects and convince them to run.

For the down-ballot races, a local county-level party chair might talk a friend into running for city commissioner or school board member. Party leaders look for charismatic people who have a good grasp of the issues and who can articulate the party’s positions. They also want candidates who can connect with voters. First-time candidates might include lifelong party volunteers, community leaders known around town, or people energized about a particular political issue.

Campaign Management

As election season draws near, political parties get busy. Everyday activities continue, but an increase in engaging voters, holding campaign events, raising money, and trying to win elections consumes the party for a months-long battle to take office and ultimately shape policy according to their ideology.

Most campaigns have a two-stage process: The parties’ rank-and-file voters nominate their candidates in a primary election, then these nominees compete against each other in the general election in November. The party and its leaders will act more like a referee in the process of candidate nomination than a coach. Factions of members will coalesce around their favorite candidates.

Sometimes these divisions are split along ideological beliefs – a primary contest might pit a liberal or conservative candidate against a more moderate one – or they could be based on differences in personality or region.

Democrats and Republicans sponsor intraparty debates or forums featuring the declared candidates. Debates enable voters to get a sense of each candidate’s principles and issue positions.

During the general election campaign, the party typically unites around its slate of nominees for different offices and works to get them elected. Parties seek success by hosting political rallies or fundraisers; canvassing for votes; distributing literature and campaign items, such as bumper stickers, signs, and buttons; making “get-out-the-vote” phone calls; and of course, running television advertising, text message campaigns, and social media outreach.

Fundraising and Media Strategy

Among the parties’ most important functions are raising and spending money in order to win elections. Popular candidates or those moving from one level of government up to the next may already have established a war chest of funds to spend. Winning an election involves travel, hotel accommodations, a small staff, yard signs, and bumper stickers. Televised and online advertising accounts for the largest part of a campaign bill.

National Party Structure

Both the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and the Republican National Committee (RNC) comprise a hierarchy of hundreds of employees and a complex network dedicated to furthering party goals. Each committee includes public leaders and other elite activists. The RNC and DNC meet formally every four years at their national conventions and on occasion between presidential elections to sharpen policy initiatives and to increase their influence.

The national chairperson is the chief strategist and spokesperson. Though a leading official such as the current president or an outspoken congressional leader tends to be the public face of the party, the party chair runs the party machinery.

Parties’ Impact on Government

In addition to their impact on voters, political parties have a significant influence on the way government works at all levels. On the national level, Republicans and Democrats construct policy, pass legislation, and maintain power. Holding the presidency allows the party in power to appoint judges who will rule on the constitutionality of laws. Holding congressional office allows members to send funding for projects to their home states. The majority party in the House and Senate controls the flow of legislation in each house and the committee chairmanships. Party control over state legislatures and governorships is also sought to shape state law and legislative district maps.

How and Why Political Parties Change and Adapt

Through a few generations, the parties have become more democratic (small ‘d’) and participatory, causing party leaders to lose some control over their nominations. Candidate-centered campaigns have become more common. In the era of television, candidates’ wealth and direct connections with voters have also weakened the party leaders’ control over candidates.

Politics is a game of addition, and both parties welcome new voters into their respective “big tent.” Parties modify their policies and messaging to bring in various demographic coalitions. As coalitions form and support parties, and when they break up to join other factions, they go through a political realignment. They modestly ebb and flow with ideology and with geographic dominance. Campaign finance and communication techniques, too, have shaped the way political parties operate.

Candidate-Centered Campaigns

Historically, voters identified with political parties more than with individual candidates. Even the mechanical voting booth—by which a person could pull one lever and vote for a single party’s entire slate of candidates—encouraged this party identification. In the 1960s, this trend began to shift, for two main reasons. First, the more widespread use of television allowed candidates to build a following based on their own personalities rather than on party affiliation.

Second, during the 1960s, society seriously questioned all public institutions, including political parties, as the Vietnam War dragged on, race riots burned cities across the nation, and the press revealed that President Nixon lied about both personal and public issues.

One result was the rise of the candidate-centered campaign. Increasingly—especially with social media and Internet technologies—candidates speak directly to the people, weakening the power of the parties. Candidates who build their own campaigns are less beholden to party elites and can wield more personal power once they are in office. For this reason, parties are forced to work closely with charismatic candidates on both platform development and campaigning for down-ticket candidates—lesser known candidates in the lower profile elections further down the ballot.

Appealing to Coalitions

Each party has its core demographic groups and continually attempts to broaden its appeal to gain more voters. A demographic group—such as Hispanics, African Americans, Millennials, women, blue-collar workers, or LGBTQ persons—voting as a bloc can determine the outcome of an election.

A party’s image during televised events such as nominating conventions can convey how inclusive it is—or isn’t—of various demographic groups.

Republican Challenges

The Republican Party faced its own challenges in appealing to a wider swath of voters. Even today, its convention delegates are overwhelmingly white, in contrast to the Democrats’ now inclusive and diverse participants. The House chamber also reflects these differences between the parties during the president’s State of the Union televised speeches. The Republican side of the aisle tends to be older, white, and male. The Democratic side of the aisle includes more women and people of color.

Demographic Coalitions

Another vital way parties appeal to their demographic coalitions is through their policy views. Will party members, if elected to office, try to overturn abortion laws, provide immigration protection, or maintain rights for gun owners to appeal to various demographic coalitions?

Different demographic coalitions have different views on these issues, and party members will shape their policy positions in part to attract the demographic groups they believe they need to win elections while still working for their ideological principles.

Changes Influence Party Structure

Parties have also adjusted to developments that affect their structure. At times throughout history, shifts in voter alignments transferred power to the opposition party and redefined the mission of each party. Campaign finance laws have brought about structural changes as well, altering the relationships among donors, parties, candidates, and interest groups. And in order to remain relevant, parties must continually adjust to changing communication technology and voter-data management systems to spread and control their message and appeal to voters.

Critical Elections and Realignments

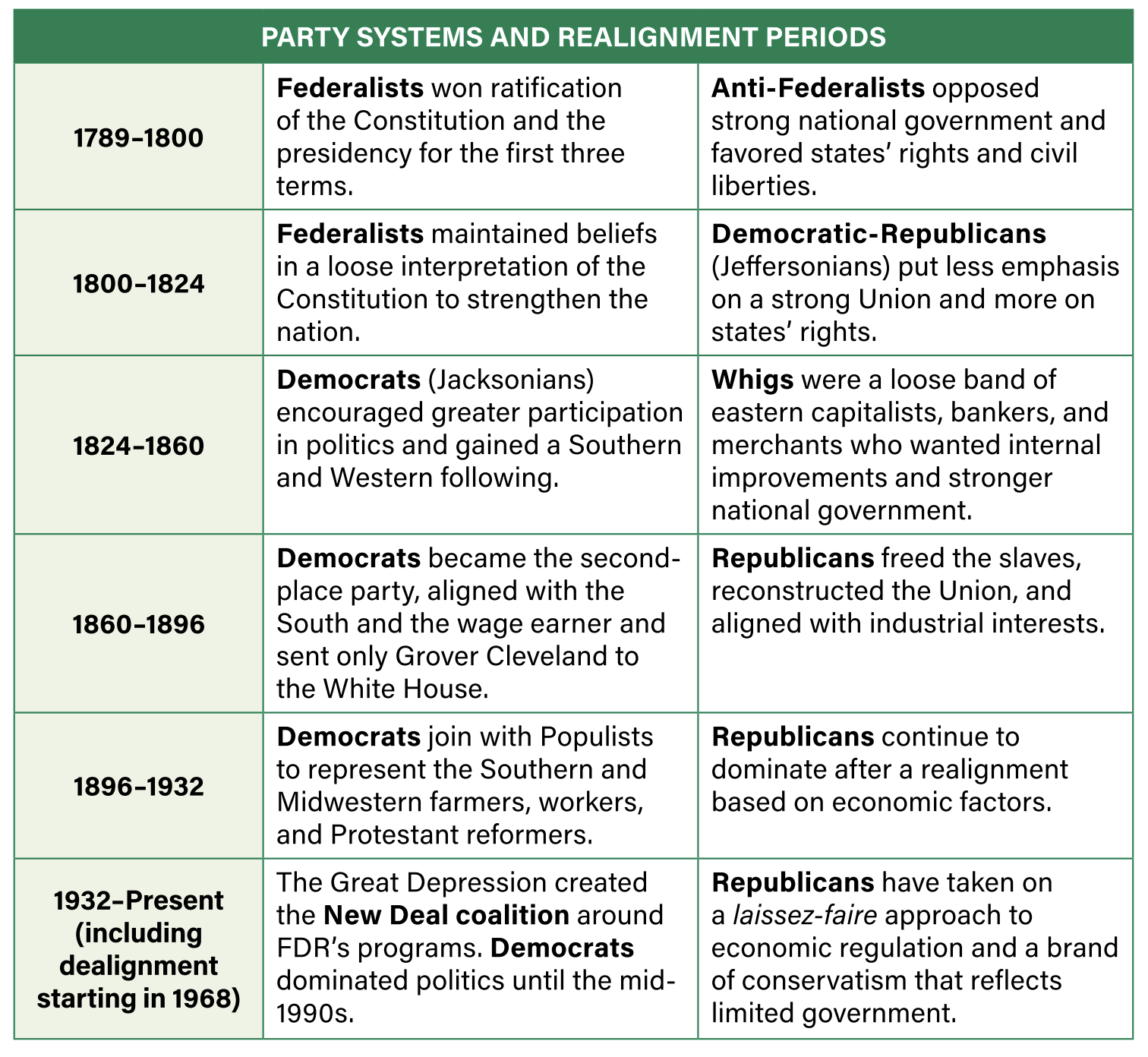

Such party realignment is simply a “change in underlying electoral forces due to changes in party identification,” according to the Oxford Concise Dictionary of Politics. Party realignments are marked by critical elections, those contests that reveal sharp, lasting changes in loyalties to political parties. Realignments may result in a shift in party dominance and may redefine the mission of each party. There are at least two causes of realignments: (1) a party is so badly defeated it fades into obscurity as a new party emerges, or (2) large blocs of voters shift party allegiance as a result of a social, economic, or political crisis.

Although political scientists and historians classify realignments differently, most agree the United States has seen five national realignments, some occasional shifts by unique groups, and some regional realignment in the post-WW II era.

The First Alignment

The Democratic-Republicans, or Jeffersonians, enjoyed two decades of dominance starting in 1800 with the decline of the Federalists. From 1824 to 1832, the Democratic Party coalesced around Andrew Jackson and followed many principles of the Democratic-Republicans. In 1828, Jackson won the presidency with support from small Western farmers. By this time, suffrage had expanded because property qualifications had been dropped in most states, and many more citizens voted. This shift toward greater democracy for the common man and away from the aristocracy that had previously held the power was called Jacksonian Democracy.

Opponents formed the Whig Party and advocated for a strong central government that would promote westward expansion, investment in infrastructure, and support these investments with a strong national bank. Both northerners and southerners joined the Whig Party. In time, the slavery issue would fracture the Whig Party.

Several party innovations developed to influence their structure. The Democrats started building state and local party organizations to help support the national party efforts. They also cultivated the custom of political patronage — that is, if victorious, they would reward those members who helped the campaign with government jobs. The Whigs and Democrats also developed more modern campaigns by holding nominating conventions.

New Alliances for the Republicans: The Second Realignment

The 1850s marked a controversial time of intense division on the issue of slavery. The 1860 election marked a national realignment with the new “Republicans” nominee, Abraham Lincoln, winning the presidency. Though the Republican Party was technically a third party at the time — the last third party to win the White House — it quickly began to dominate national politics. The immediate secession by so many southern Democrats from the House and Senate intensified the Republicans’ dominance in Washington during the Civil War years.

Today, the Republicans are often referred to as the “Grand Old Party” or GOP. From 1860 to 1932, Republicans dominated national politics with their pro-growth, pro-business agenda. As African Americans began to vote, they sided invariably with the party that freed them, the Republican Party. Democrats continued to be strong in the South. The Democrats also took in large numbers of immigrants, Catholics, and factory workers in their northern cities.

Expanding Economy and the Realignment of 1896

The next realignment point came during the era of big business and expansion, with Republicans still dominant. The critical 1896 election realigned voters along economic lines. The economic depressions of the 1880s and 1890s (or panics, as they were often called) hit the South and the Midwest hard. The Democratic Party joined with third parties such as the Greenbacks and Populists to seek a fair deal for the working class and represent voters in the South and West. Democrats also supported Protestant reformers who favored prohibition of alcohol.

For the 1896 presidential election, congressman and orator William Jennings Bryan captured the Democratic nomination. The Populist Party also endorsed him. However, anti-Bryan Democrats realigned themselves with the Republican Party, which nominated William McKinley. The Republicans were still aligned with big business, industry, capitalists, urban interests, and immigrant groups. These groups feared the anti-liquor stance of so many in the evolving Democratic Party, which increasingly focused on class conflict and workers’ rights. As Democratic legislatures began to regulate industry to protect laborers, conservative Republican judges declared such regulations unconstitutional.

These differences began the division that continues today between Republican free-market capitalists and Democrats who favor regulation.

Democrats, the Depression, and the Fourth Realignment

In the 1930s during the Great Depression, America went from being mostly Republican to being solidly Democratic thanks to Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal coalition, which was made up of Democratic state and local party organizations, labor unions and blue-collar workers, minorities, farmers, white southerners, people living in poverty, immigrants, and intellectuals.

The 1932 presidential election marked the first time that more African Americans voted Democrat than Republican, a loyalty that grew stronger and remains today. This massive coalition sent Roosevelt to the White House four times. His leadership during the economic crisis and through most of World War II allowed the Democrats to dominate Congress for another generation. The New Deal implemented social safety nets and positioned the federal government as a force in solving social problems. It reined in business, promoted union protections and civil liberties, and increased participation by involving women and minorities.

Shifts Since the 1960s

Although a mix of politicians from both parties favors equality among the races, the post-World War II fight for equality for African Americans was dominated by the liberal northern wing of the Democratic Party. President Lyndon Johnson accurately predicted the Democratic Party would lose the South for a generation when he signed the Civil Rights Act in the summer of 1964. (See Topic 3.11.)

In November 1964, a regional realignment became apparent after the presidential election between President Johnson and Arizona Republican Barry Goldwater. Johnson handily won nationally, while Goldwater won the Deep South states, a region that had served as the “Solid South” for Democrats for most presidential elections over the previous century. Most scholars mark 1968 as the breakup of the New Deal coalition and the beginning of an era of divided government – a situation in which one party controls Congress and the other controls the White House.

Today, southern White voters have all but left the New Deal coalition and joined the Republican Party. Additionally, decisions that resulted in busing public school children for racial balance and those that legalized abortion convinced conservative voters to move to the GOP. Yet, many of the voting blocs that backed FDR in the 1930s continued to stick together at election time for the Democrats: laborers, Jews, African Americans, urbanites, and academics.

Since 1968, the major parties have continued on similar ideological paths, especially on economic issues. However, a growing number of citizens became independents or turned away from politics altogether, resulting in a party dealignment. The unpopular Vietnam War and Richard Nixon’s Watergate scandal brought mistrust of government and a mistrust of the parties. Voter turnout dropped over the following three decades. Party loyalty decreased, a fact made obvious by an increased number of independent voters. These voters split their tickets-or voted for candidates from both parties- which resulted in divided government, common at the federal level.

The Democratic Party has gone from supporting states rights and raw capitalism to believing in big government and national regulations, while the Republican Party has gone from being the progressive anti-slavery party to one that is fiscally conservative and denounces affirmative action. These drastic transitions did not happen overnight but through a series of changing voter habits and adjusted party alignments over more than a century.

Changes in Communication and Data-Management Technology

Political parties rely heavily on polling and on mining databases to gain insights into voter preferences, so they must quickly adapt to changes in technology. President Obama’s campaigns, especially for his reelection in 2012, devoted many resources to using available technology and media to their fullest to understand and target voters. Parties use this information to craft, control, and clarify their messages.

Voter data can reveal where people eat and shop, the people they’re connected to, and which media sources they use to access news and information. Increasingly, political organizations are able to target with pinpoint accuracy who gets which message thanks to data-management technology. Data-management technology is a field that uses skills, software, and equipment to organize information and then store it and keep it secure.

These digital resources are so valuable in learning about voters that they have been abused. Before the 2016 election, a British political data firm called Cambridge Analytica managed to obtain 50 million Facebook user profiles from another company’s personality quiz app. The data firm was an offshoot of the SCL Group, a company owned largely by the Mercer family, which includes conservative billionaire Republican Party supporters. Cambridge Analytica then created detailed “psychographic” profiles used to target voters during the campaign. Facebook suspended Cambridge Analytica and found itself in the crosshairs over its oversight and corporate policies and the role it played in presidential politics.

Managing Political Messages and Outreach

Demographics explain “who” the voters are-race, gender, age, neighborhood, church or political affiliation, and similar traits. Psychographic segmentation uses data about personality, lifestyle, and social class to categorize groups of voters. Psychographics, in contrast to demographics, explains “why” they vote the way they do. What are their values, hobbies, habits, and likes? This valuable information helps candidates and parties tailor their messages and conduct political outreach.

Part of a message’s appeal is based on the candidate’s appearance and choice of venues for delivery. A Western state candidate might appear wearing a cowboy hat and boots, riding on horseback along a river. An urban candidate could roll up her sleeves and visit a public works project that rehabilitates neighborhoods.

Language is carefully crafted in messages to remind voters of key ideas and values espoused by the party.

Another key element of messaging and outreach is timing. In the early stages of a campaign, more abstract messages resonate. That’s when the candidate will remind voters about core values and ideals. For instance, during the 2008 presidential primaries, Democrat Barack Obama spoke enthusiastically of hope and change, while his rivals focused on the concrete details of managing the Iraq War and closing a “doughnut hole” in Medicaid that made drug costs out of reach for some. Closer to election day, voters become receptive to messages that are more concrete. Candidates can specify the programs they plan to implement and how those changes will improve the lives of Americans.

Perhaps the greatest challenge for parties is to spark interest in unaligned or apathetic voters. In recent elections, Barack Obama succeeded in doing this and won elections in 2008 and 2012 with his brand and message of hope and change. In 2016, Donald Trump won the election by promising a very different brand of change – draining the Washington swamp of corrupt insiders.

Third-Party Politics

Political parties can afford people with similar beliefs the opportunity to participate in government. These parties are often influenced by special interest groups and social movements, and their goal is always to capture the largest share of the votes possible so that they can wield power. The United States has traditionally had a two-party system that discourages third-party and independent candidates, especially at the national level.

At times in the nation’s history, third parties have surfaced and had an impact in politics. Often these parties come and go and enjoy only a limited amount of success in winning elections. Structural barriers within the electoral system and barriers outside of it prevent these organizations from gaining the traction necessary to fully succeed. Yet they can influence policy and play a significant role, especially because voters are so evenly split among their loyalties to the two major parties.

Third-Party and Independent Candidates

Though a two-party system has generally dominated the American political scene, competitive minor parties, often called third parties, have surfaced and played a distinct role. Technically, the Jacksonian Democrats and Lincoln’s Republicans began as minor parties. Since Lincoln’s victory in 1860, no minor party has won the White House, but several third-party movements have met with some levels of success. These lesser-known groups have sent members to Congress, helped add amendments to the Constitution, and forced the larger parties to take note of them and their ideas. Despite these victories, structural barriers in our political system have limited the impact and influence-and therefore the success-of third-party and independent candidates.

Why Third Parties Form

Because the two major parties compete to win the majority of voters, and majorities always occupy the center of our political spectrum, the more ideological citizens may believe neither major party hears or implements their desired agenda, so they create their own party. For instance, in the early 1900s as a response to conservative robber barons, uncontrolled industrial growth, and massive wealth inequality, the Socialist Party formed and introduced a leftist agenda whose ideas were eventually incorporated into American politics.

During the 1970s, following a long period of Democratic dominance, the Libertarian party formed. Its supporters wanted a more traditional liberalism: laissez-faire (unregulated) capitalism, abolition of the welfare state, nonintervention in foreign affairs, and individual rights-such as the right to opt out of paying into Social Security and receiving its benefits. Socialists and Libertarians are ideological parties because they subscribe to a consistent ideology across multiple issues.

Sometimes third parties form as splinter parties when large factions of members break off from a major party. In 1912, when former President Teddy Roosevelt wanted to return to the White House and sought the Republican nomination, the party instead renominated their incumbent, William Howard Taft. When Roosevelt lost the vote at the Chicago convention, he immediately declared he would run for president anyway. To one inquiring reporter he responded that he felt as strong as a Bull Moose. The new Progressive Party formed around him, nicknamed the Bull Moose Party.

Another example came in 1968 when segregationist George Wallace splintered off from the liberal-leaning Democratic Party and formed the American Independent Party. White southerners followed him, splitting the Democratic vote, and that-along with opposition to the Vietnam conflict and Humphrey’s non-democratic nomination-led to the election of Republican Richard Nixon.

In both cases, these third parties failed to win the presidency, but their impact spoiled the outcome for the parties they departed. When a strong personality or a politician with a following appears to consider splintering off and taking his supporters along, the party will treat them and their ideas differently, hoping they stay in the tent. And if the splintering happens and the party loses the election, it will consider the group’s desires and add them to their agenda or platform to prevent a loss next time.

Modern Third Parties

Since 1968, there have been additional minor party candidates seeking the presidency, but no such candidate has won a plurality in any one state, and therefore none has ever earned even one electoral vote. Texas oil tycoon H. Ross Perot burst onto the political scene in 1992 to run for president as an independent. Funded largely from his own wealth, Perot created United We Stand America (later renamed the Reform Party) and campaigned in every state. He won nearly 20 percent of the national popular vote. But with no strong following concentrated in any one state, he failed to earn any electoral votes.

Perennial candidate Ralph Nader was the Green Party candidate in the 2000 election. ‘The votes he drew from Democrat Al Gore likely helped propel Republican George W. Bush into the presidency in a very close election. After Nader allegedly spoiled it for the Democrats, the party did what it could to keep him off the swing states’ ballots in 2004.

Barriers to Third-Party Success

No minor party has won the presidency since 1860, and no third party has risen to second place in the meantime. Minor parties have a difficult time competing with the highly organized and well-funded Republicans and Democrats. The minor parties that come and go cannot effectively participate in the political process in the United States, at national, state, and local levels, because the institutional reasons for the dominance of the two major parties are many and complex. They include single-member districts, money and resources, the ability of the major parties to incorporate third-party agendas and winner-take-all voting.

Single-Member Districts

The United States generally has what are called single-member districts for elective office. In single-member districts, the candidate who wins the most votes, or a plurality in a field of candidates, wins that office. Many European nations use proportional representation. In that approach, multiple parties compete for office, and voters cast ballots for the party they favor. After the election those offices are filled proportionally. For example, a party that wins 20 percent of the votes cast in the election is then awarded 20 percent of the seats in that parliament or governing body. This method encourages and rewards third parties, even if minimally. In nearly all elections in the United States, contests are within a local, defined geographic district. If three or more candidates seek an office, the candidate winning the most votes even if it is with a minority of the total votes-wins the office outright. ‘There is no rewarding second, much less third, place.

Money

Minor party candidates also have a steeper hill to climb in terms of financing, ballot access, and exposure. The Republican and Democratic parties have organized operations to raise money to convince donors of their candidates ability to win-and by so doing attract even more donors. Full-time employees at the DNC and RNC constantly seek funding between elections. Even more important, according to campaign finance law, the nominee’s party needs to have won a certain percentage of the vote in the previous election in order to qualify for government funding in the current election. Political candidates from minor parties have a difficult time competing financially unless they’re self-financed, as was Ross Perot.

Independents also have a difficult time with ballot access. Every state has a prescribed method for candidates to earn a spot on the ballot. It usually involves a fee and obtaining a minimum number of signatures. The Democratic and Republican candidates have the advantage of a strong, existing party network. They can simply dispatch party regulars and volunteers throughout a state’s counties to collect signatures for the ballot petition. The statewide director can set goals for signatures that each county chairman is meant to obtain. Green Party, Libertarian, or independent candidates must first secure assistance or collect those signatures themselves or with only a meager party organization.

Since a ballot petition often requires thousands of registered voters, this task alone is daunting and discouraging to potential third-party candidates.

The media tend not to cover minor party candidates. Independents are rarely invited to public debates or televised forums at the local and national levels. Buying exposure and support through advertising costs millions of dollars. So, for third parties it is hard to get noticed.

Incorporation of Third-Party Agendas

Throughout U.S. history, there have been 52 independent political parties, yet none of them has gained traction. No one other than a Democrat or a Republican has been elected since 1860. Does that mean third parties play no role other than annoyance and spoiler for the major parties? Definitely not.

In order to attract the third-party candidates voters, the most closely aligned major party will often incorporate items from that party’s agenda into its platform. Although this practice serves to discourage third-party candidates from running, it can also result in positive social change. For instance, Socialists promoted women’s suffrage and child labor laws in the early 1900s, now taken for granted by both parties. Populists eventually got Americans a 40-hour work week. Ross Perot planted the idea of a balanced federal budget in the national consciousness. Ralph Nader fought for consumer protections and a clean environment. Minor parties play an important role as the conscience of the nation.

Since the first political contests before the Republic was created, most citizens have fallen into two camps with very different points of view about how government should be run. Parties provide an identity that simplifies the task of parsing important issues for members. Yet, this simplification can also be divisive. More and more Americans are looking for ways to stop being “red” or “blue” (the colors typically used on election maps, with states that voted Republican colored red and states that voted Democratic colored blue).

Most Americans want practical compromises to solve big problems. This is the challenge for the two-party system: for each to hold on to its base voters while appealing to the middle.

Winner-Take-All Voting

Perhaps the largest barrier is the winner-take-all system of the Electoral College. The Electoral College determines the presidential candidate, but the popular vote within each state determines how the electors cast their ballots.

All states, with the exception of Maine and Nebraska, award all their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the plurality of the popular vote, a process called the winner-take-all voting system. The biggest problem for third-party and independent candidates is that they very rarely win a state’s popular vote and thus can’t accumulate the required 270 electoral votes to win, nor do they even appear to have potential as no third-party candidate has won electoral votes since 1968. This challenge discourages independent voters from considering third-party candidates because they feel they are throwing their votes away.

With winner-takes-all voting, swing states–those that could go either way in an election-tend to get most of the attention. Swing states, sometimes called battleground states, shift party resources to certain regions, and third-party and independent candidates always have trouble matching that level of investment.