Concepts illustrated in this case study:

Border/Boundary Disputes

definitional

locational

operational

allocational

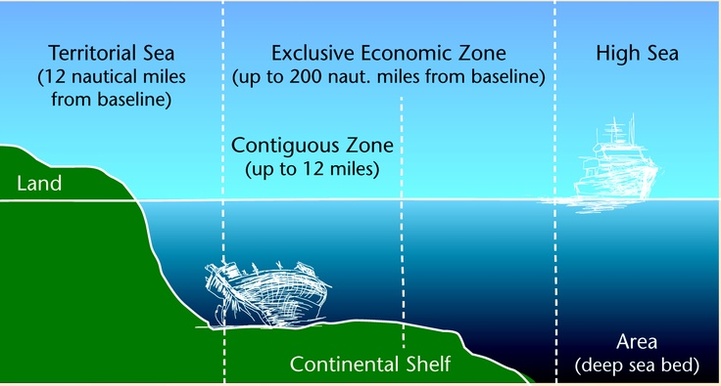

Law of the Sea

coastline

territorial waters

contiguous zone

exclusive economic zone (EEZ)

international waters

Law of the Sea (borders in the ocean)

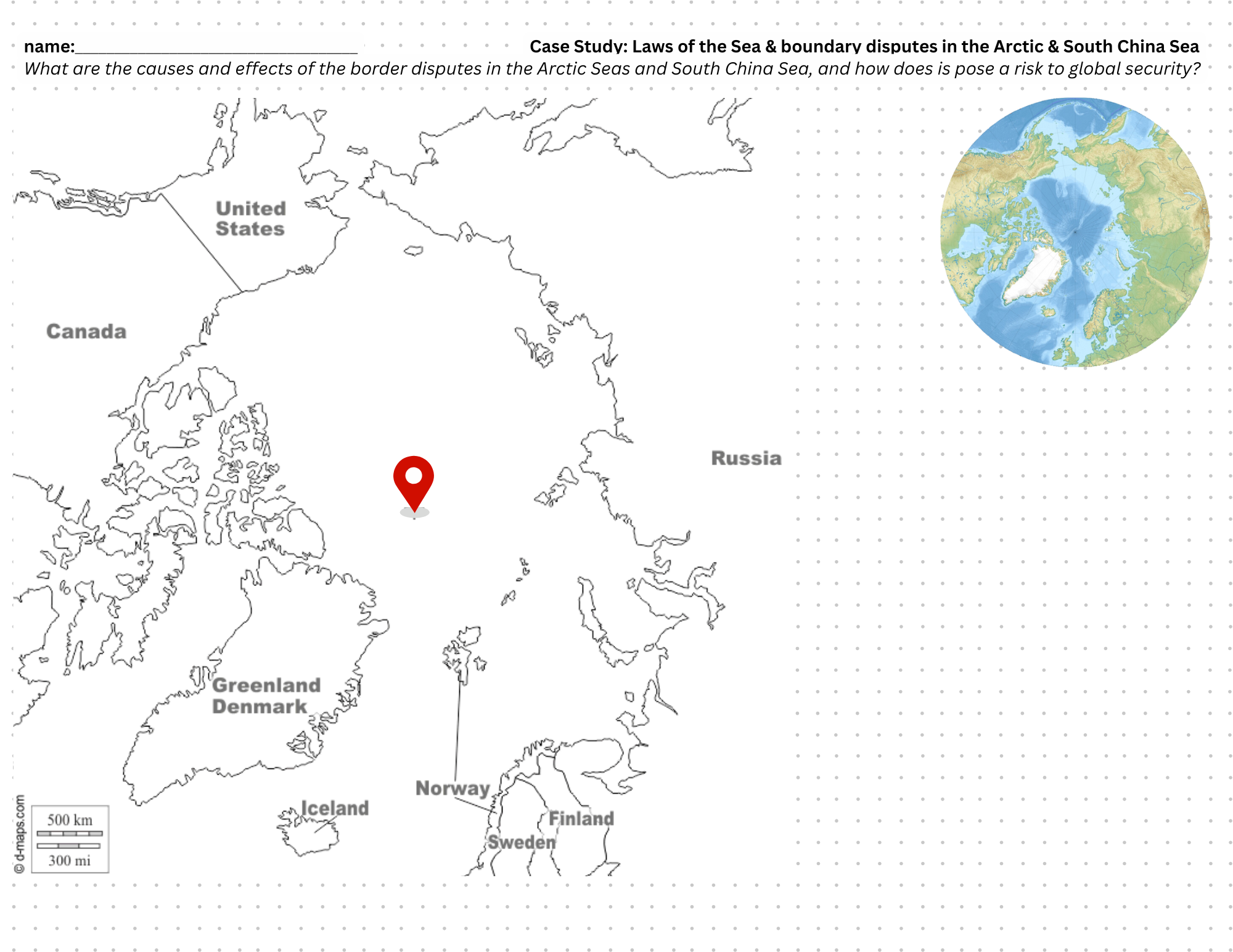

Territoriality & Boundary Disputes in the Arctic Sea

Territoriality & Boundary Disputes in the South China Sea

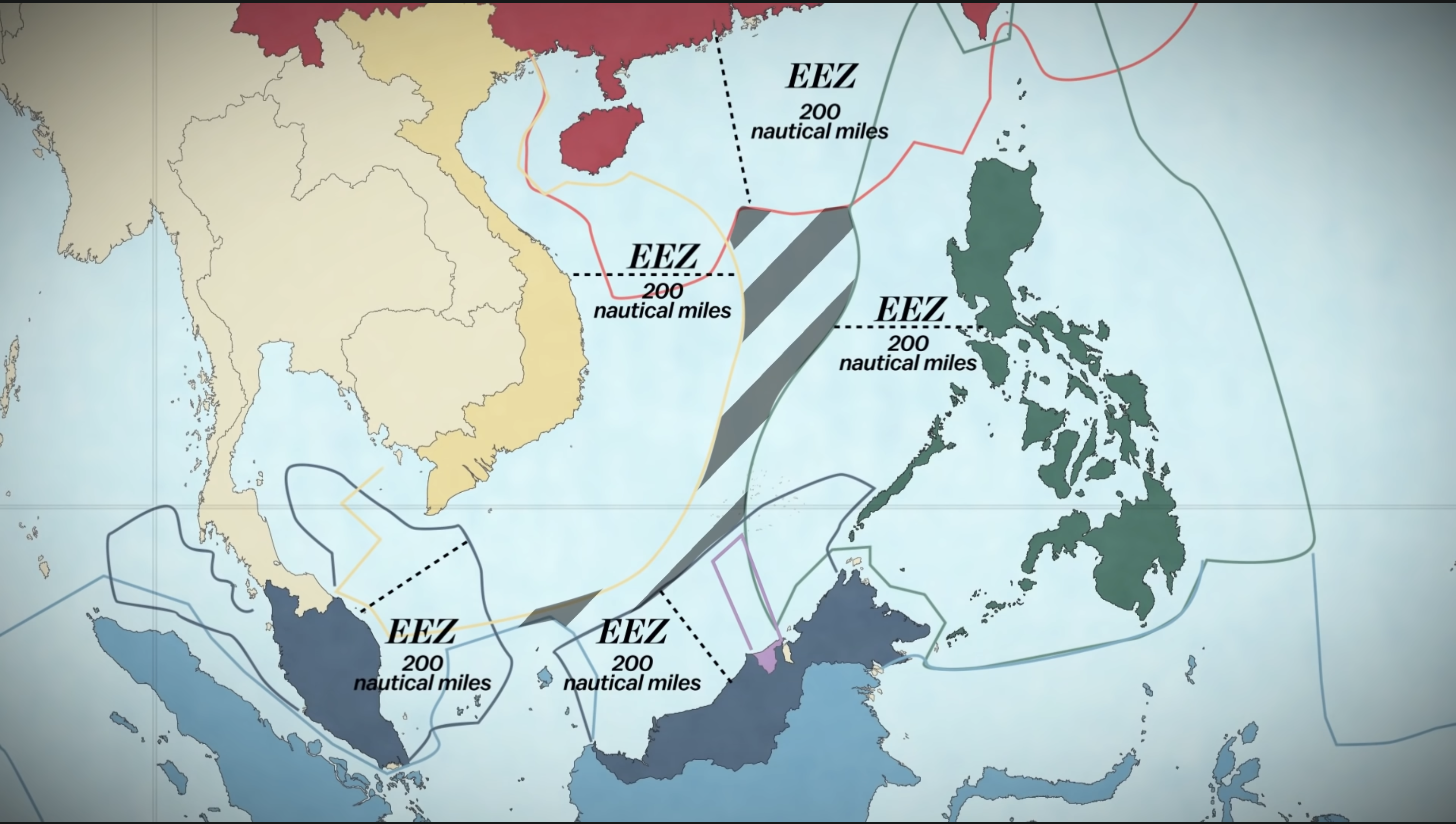

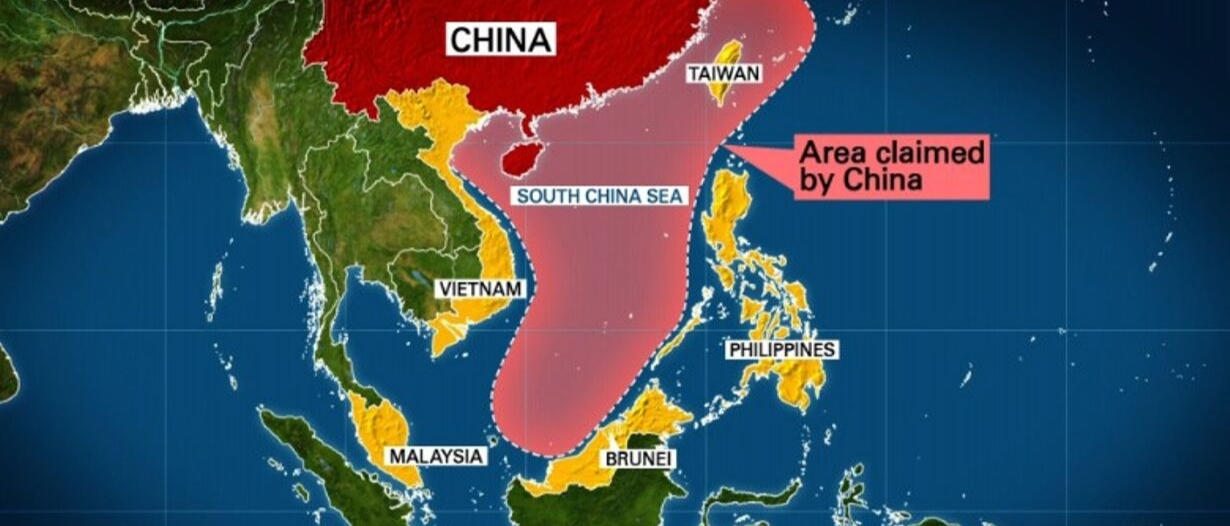

China, Spratly Islands, and the South China Sea Dispute

The South China Sea is a strategically vital and resource-rich region that has been the center of intense geopolitical disputes. Multiple nations, including China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, claim overlapping portions of this body of water. At the heart of the conflict lies the interpretation and application of maritime zones established by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), particularly territorial waters, contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones (EEZs), and international waters.

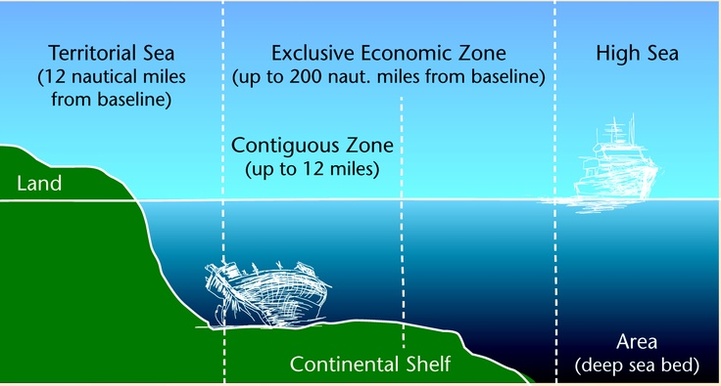

Territorial Waters

Under UNCLOS, a coastal state has sovereignty over its territorial waters, which extend up to 12 nautical miles from its baseline. Within this zone, the state has the same legal authority as it does on its land territory. In the South China Sea, several countries, including China, Vietnam, and the Philippines, claim territorial waters around various islands, reefs, and rocks. However, disagreements arise when these 12-mile zones overlap due to the close proximity of land features claimed by multiple states.

Contiguous Zone

Beyond territorial waters lies the contiguous zone, which extends up to 24 nautical miles from the baseline. In this zone, a state can exercise control to prevent and punish infringements of its customs, immigration, or sanitary laws. While the contiguous zone does not grant full sovereignty, it provides a buffer where nations can assert limited jurisdiction. For instance, China uses its claims over certain islands to extend its contiguous zone into contested waters, which other nations argue infringes on their maritime rights.

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)

The EEZ extends up to 200 nautical miles from a country’s baseline, granting the coastal state exclusive rights to exploit marine resources, including fishing, oil, and gas. This is a significant factor in the South China Sea dispute, as the region is estimated to contain vast reserves of hydrocarbons and hosts some of the world’s richest fishing grounds. China’s controversial “Nine-Dash Line”, which encompasses most of the South China Sea, overlaps with the EEZs of several other nations. This has led to legal challenges, such as the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling in favor of the Philippines, which invalidated China’s Nine-Dash Line claims under international law. However, China rejected the ruling and has continued to assert its expansive claims.

International Waters

Outside of any nation’s territorial waters, contiguous zone, or EEZ are international waters, also known as the high seas. These areas are open to all states for freedom of navigation and overflight. The South China Sea contains some international waters, but their extent is limited due to overlapping claims from surrounding nations. Tensions often escalate when military vessels from non-claimant nations, like the United States, conduct “freedom of navigation operations” (FONOPs) to challenge China’s claims and assert the principle that parts of the South China Sea remain international waters.

The Role of Maritime Zones in the Dispute

The South China Sea dispute highlights the strategic use of maritime zones in asserting sovereignty and control over resources. China’s construction of artificial islands and military installations in contested areas aims to bolster its claims to extended territorial waters, contiguous zones, and EEZs. Conversely, smaller claimant nations rely on UNCLOS to defend their rights, particularly their EEZs, against what they view as encroachments by a more powerful neighbor.

Ultimately, the South China Sea remains a flashpoint for regional and global tensions, with maritime zones serving as both a framework for conflict resolution and a basis for competing claims. Understanding these zones is essential for navigating the complex legal and geopolitical dynamics at play in this critical region.

Territorial Disputes in the Arctic Ocean

The Arctic Ocean has become a focal point for territorial disputes as climate change melts sea ice, opening new shipping routes and exposing vast untapped reserves of oil, gas, and other resources. Under the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Arctic nations are vying to expand their maritime boundaries, leading to overlapping claims and geopolitical tensions.

Territorial Waters and Contiguous Zones

Under UNCLOS, nations bordering the Arctic Ocean—Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark (via Greenland), and the United States—have sovereignty over their territorial waters, which extend 12 nautical miles from their respective coastlines. These nations also control a contiguous zone, which extends up to 24 nautical miles, allowing them to enforce laws related to customs, immigration, and security.

While territorial waters and contiguous zones are generally well-defined, disputes arise over the classification and ownership of specific Arctic landforms, such as the Lomonosov Ridge and the Alpha-Mendeleev Ridge. Control over these features could extend a nation’s rights to resources far beyond their typical territorial waters.

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs)

The Arctic nations are entitled to exclusive economic zones (EEZs) extending 200 nautical miles from their coastlines, granting them exclusive rights to exploit resources in these waters. However, overlapping EEZs have fueled disputes, such as:

- Russia and Norway: These nations resolved some disputes in the Barents Sea through a 2010 treaty, but competition persists over fishing and hydrocarbon resources near the EEZ boundaries.

- Canada and the United States: Both countries claim sovereignty over the Beaufort Sea, particularly over regions thought to hold large oil and gas deposits.

- Denmark (Greenland) and Canada: Disputes exist over portions of the Lincoln Sea and the tiny, uninhabited Hans Island, located between Greenland and Canada.

The Extended Continental Shelf and Arctic Claims

The most significant Arctic disputes stem from claims to the extended continental shelf, a seabed area that can extend beyond the EEZ if a nation proves that the seabed is a natural prolongation of its landmass. Under UNCLOS, nations can submit scientific evidence to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to support these claims.

- Russia’s Claims: Russia has been particularly assertive, submitting evidence to the CLCS to claim large portions of the Arctic Ocean, including the Lomonosov Ridge and the North Pole. Russia’s claims overlap with those of Canada and Denmark, leading to disputes over who has legitimate rights to these areas.

- Canada and Denmark: Both nations have submitted overlapping claims to the CLCS regarding parts of the Arctic seabed, including the North Pole. These claims are based on the same geological features, particularly the Lomonosov Ridge.

- United States: As a non-signatory to UNCLOS, the United States cannot formally submit claims to the CLCS. However, it continues to assert its rights in the Arctic through domestic legislation and military presence.

International Waters and Strategic Competition

Beyond territorial waters, contiguous zones, and EEZs lies the high seas, or international waters, where no single nation has sovereignty. However, the Arctic Ocean’s high seas are limited, as the overlapping claims of Arctic nations reduce their extent. International cooperation is governed by agreements like the Arctic Council and the Ilulissat Declaration, but these frameworks face challenges due to rising geopolitical tensions.

- Shipping Routes: Melting ice is opening critical passages, such as the Northern Sea Route (claimed by Russia) and the Northwest Passage (claimed by Canada), which are contested as international waters by other nations, including the United States.

- Military Posturing: Russia has increased its military presence in the Arctic, constructing bases and deploying icebreakers to assert control over key areas. This has prompted other nations, including NATO members, to bolster their Arctic defenses.

The Future of Arctic Disputes

As the Arctic becomes more accessible, the territorial disputes are likely to intensify. Resolving these disputes requires balancing national interests, international law, and the need for sustainable development. With resources and strategic dominance at stake, the Arctic Ocean remains a critical arena for geopolitical competition and international negotiation.