Causes & Innovations

steam engine

natural resources & capitol

spinning Jenny

power loom

Effects For

work

cottage industry

social classes & inequality

demographic changes

migration & urbanization

agriculture & food supply

colonialism & imperialism

Economic activity and development have brought dramatic changes to the world. Industry, the process of using machines and large-scale processes to convert raw materials into manufactured goods, has stimulated social, political, demographic, and economic changes in societies at all scales. Industry requires raw materials, the basic substances such as minerals and crops needed to manufacture finished goods.

Growth and Diffusion of Industrialization

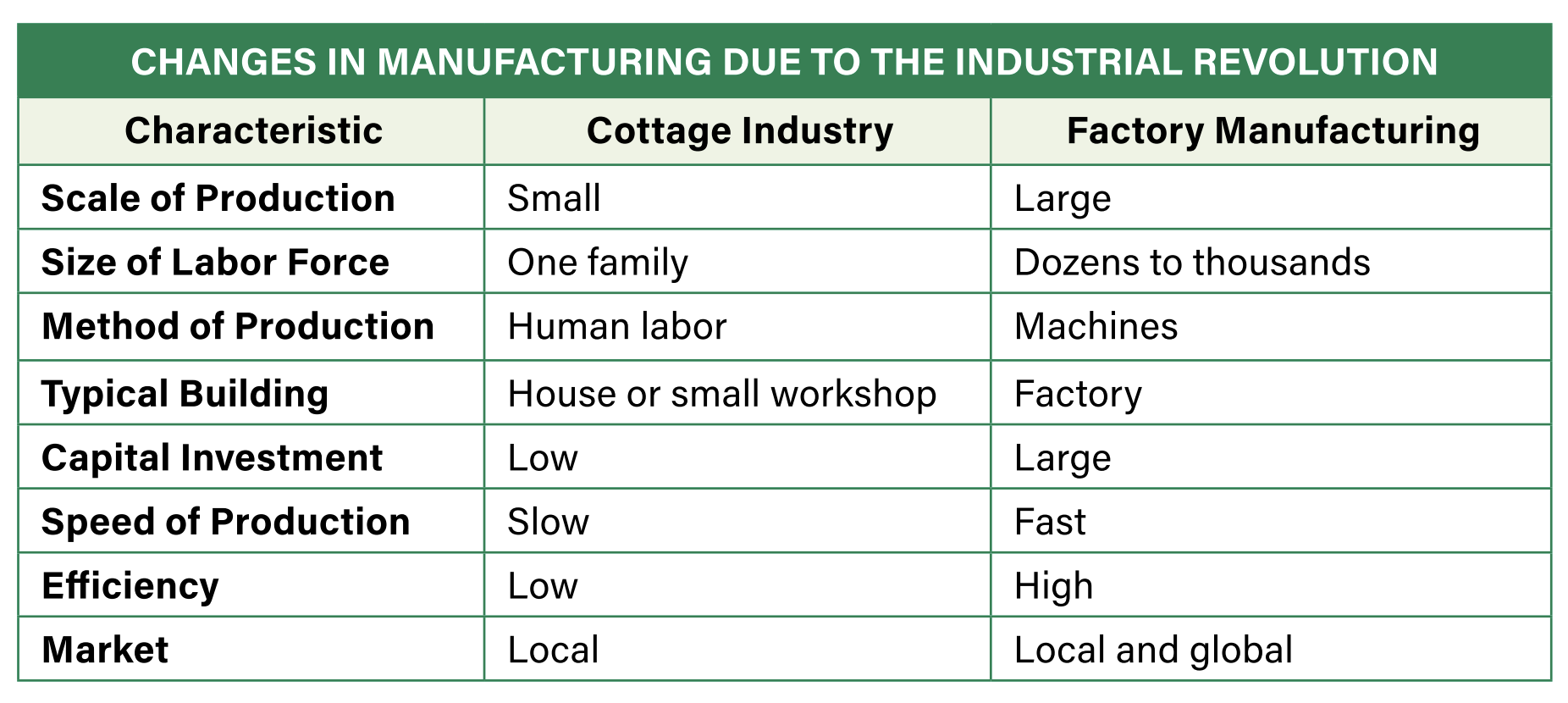

Before the 18th century, people made for themselves most clothes, tools, and other items they used. They bought only a few items, often textiles or metal goods, in a market, a place where products are sold. What they did buy was usually made by other families working in their own homes who had a contract to make products for a merchant. These small home-based businesses that made goods are called cottage industries. These industries depended on intensive human labor since people used simple spinning wheels, looms, and other tools.

Starting in the 18th century, a series of technological advances known as the Industrial Revolution resulted in more complex machinery driven by water or steam power that could make products faster and at lower costs than could cottage industries. Because the new machinery was so large and required so much investment money, or capital, manufacturing shifted from homes to factories. The replacement of labor-intensive cottage industry with capital-intensive factory production reshaped not only how people worked, but where they lived and how they related to each other spatially.

The Industrial Revolution spread throughout the world. However, cottage industries remain important, especially in less-developed countries. Many families survive by producing and selling items such as hand-woven fabric and rugs in both local and global markets. Wealthy consumers are willing to pay more for high-quality handcrafted products than they would pay for mass-produced items.

Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution

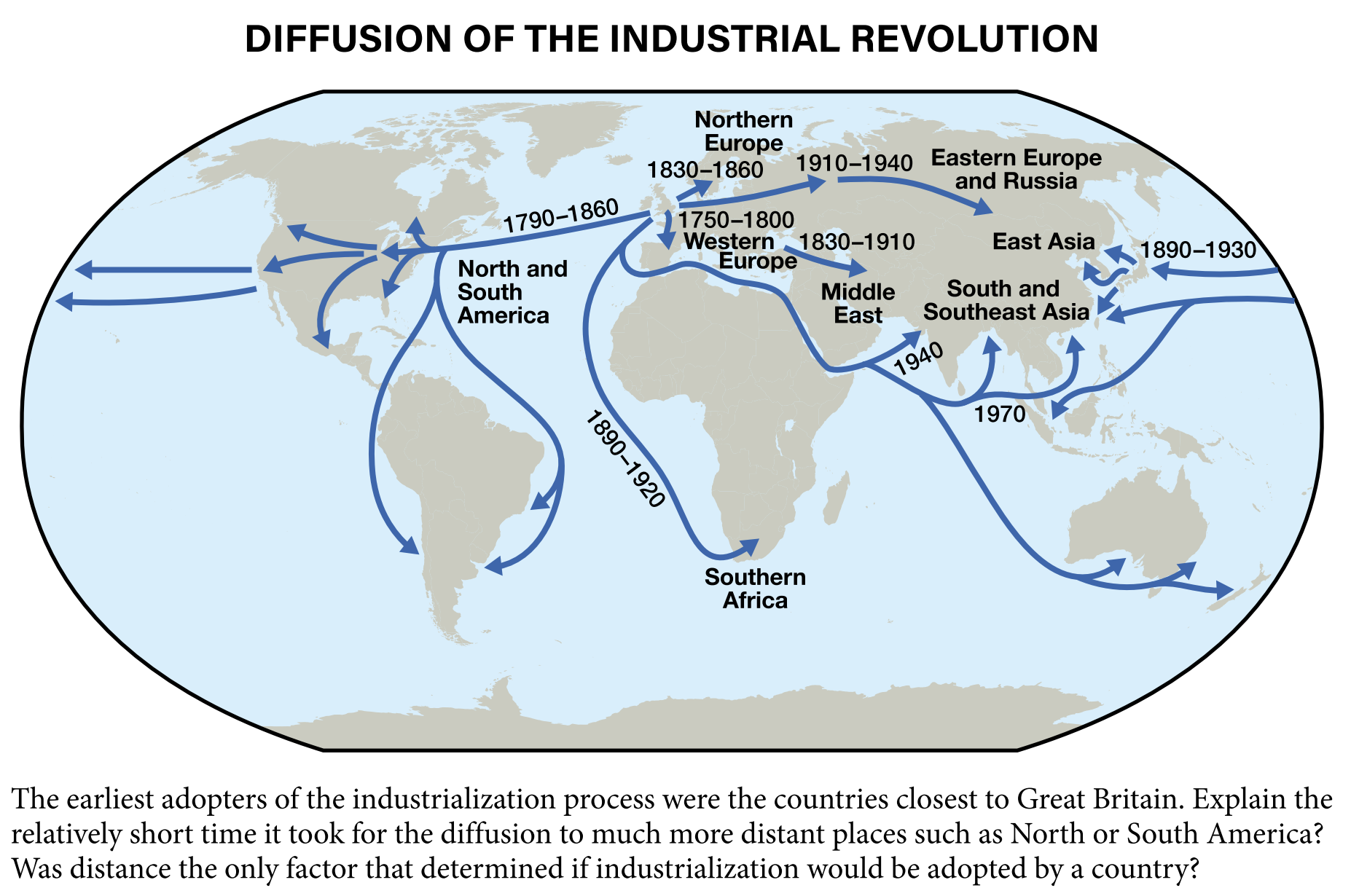

Starting in the mid-1700s, the Industrial Revolution diffused rapidly on a regional scale and then a global scale. From Great Britain it moved first to nearby France and the Netherlands. By the mid-1800s, industrialization had spread east to Germany and west to the United States. By the early 1900s, it had reached all of Europe, Japan, parts of China, and South America. Today, most of the world is industrialized.

On the local scale, investors originally considered three main factors in choosing where to build a factory:

- Energy resources to provide power, such as rivers or coal deposits

- Minerals or agricultural products needed for producing goods

- Transportation routes, such as roads, rivers, canals, and ports

As new forms of transportation and electricity were developed during the 19th century, industries became less dependent on the location of local coal supplies and companies could build factories in more diverse locations.

As factories grew larger, their location near a large workforce became more important. Hence, factories began to cluster in cities. These population centers also provided a market for the products made in a factory. As the Industrial Revolution progressed, improvements in farm machinery and farming techniques—the Second Agricultural Revolution—increased agricultural productivity. Machine power replaced human and animal power. As a result, society needed fewer people to work on farms. These displaced farm workers moved to cities in search of work. Industrialization, then, promoted greater urbanization.

Growth of Cities and Social Class Changes

The growth of cities and factories reinforced each other. Factory work drew people to cities, who provided a market for factory goods. The greater availability of goods attracted more people. For example, London grew from one million people in 1800 to six million in 1900.

Such rapid urban growth brought problems. Old systems for handling human waste, burying the dead, and cleaning up horse manure were overwhelmed. Disease was rampant. Since people burned wood and coal to heat their homes and run factories, air pollution increased to harmful, even deadly, levels. At times, smog caused the normal death rate to double. Over time, people supported stronger government action—such as building sewers and regulating cemeteries—to protect public health.

Industrialization changed the class structure of society significantly. Before industrialization, most people worked with their hands, usually on farms or sometimes in a craft. A tiny elite class of people were wealthy landowners or church leaders. In between these two classes was a small class of merchants, clergy, and others who relied more on their knowledge than on their physical skills. With industrialization, this middle class expanded rapidly. Industry needed factory managers, accountants, lawyers, clerks, and secretaries. In addition, as the demand for workers who could read and write increased, so did the demand for teachers and professors. Class differences were stark:

- In rural areas, the mechanization of agriculture drove people away, but those who were able to stay benefited from the increased productivity.

- The urban working class who were employed in factories had hard and dangerous jobs, lived in crowded conditions in polluted areas, and often could not afford to purchase the products they made.

- People in the expanding urban middle class had more comfortable lives and enough income to purchase the low-cost manufactured goods.

- Some factory owners, bankers, and others in business in urban areas became extremely wealthy.

- Landowners often maintained their control of land, but they lost much of the influence in society to the rising business-oriented class.

Physical Changes in Cities

Cities grew both outward (horizontally) and upward (vertically). Horizontally, improvements in intra-urban transportation, such as trains, cars, and trucks, allowed cities to spread out farther from the downtown core. People could live farther from their workplace and still commute to work easily. At the same time, producers could transport food from the countryside into cities to feed a growing population.

Vertically, the development of elevators, stronger and more affordable steel, and techniques to construct stronger foundations combined to allow for people to construct taller buildings. As taller buildings made city populations more dense, public health measures became increasingly important.

Colonialism, Imperialism, and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution built on the earlier rise of imperialism, a policy of extending a country’s political and economic power. As countries such as Great Britain and France industrialized, they desired to control trading posts and colonies around the world. They also looked to colonies to provide various resources:

- raw materials such as sugar, cotton, foodstuffs, lumber, and minerals for use in mills and factories

- labor to extract raw materials

- markets where manufacturers could sell finished products

- ports where trading ships could stop to get resupplied

- capital from profits for investing in new factories, canals, and railroads

By the early 1900s, several European countries and the United States had colonies around the globe. The development of imperialism made wealthy countries even wealthier, leading to a greater divide between the advanced, industrialized states and the underdeveloped, nonindustrialized states.

Major Industrialized Regions of the World Today

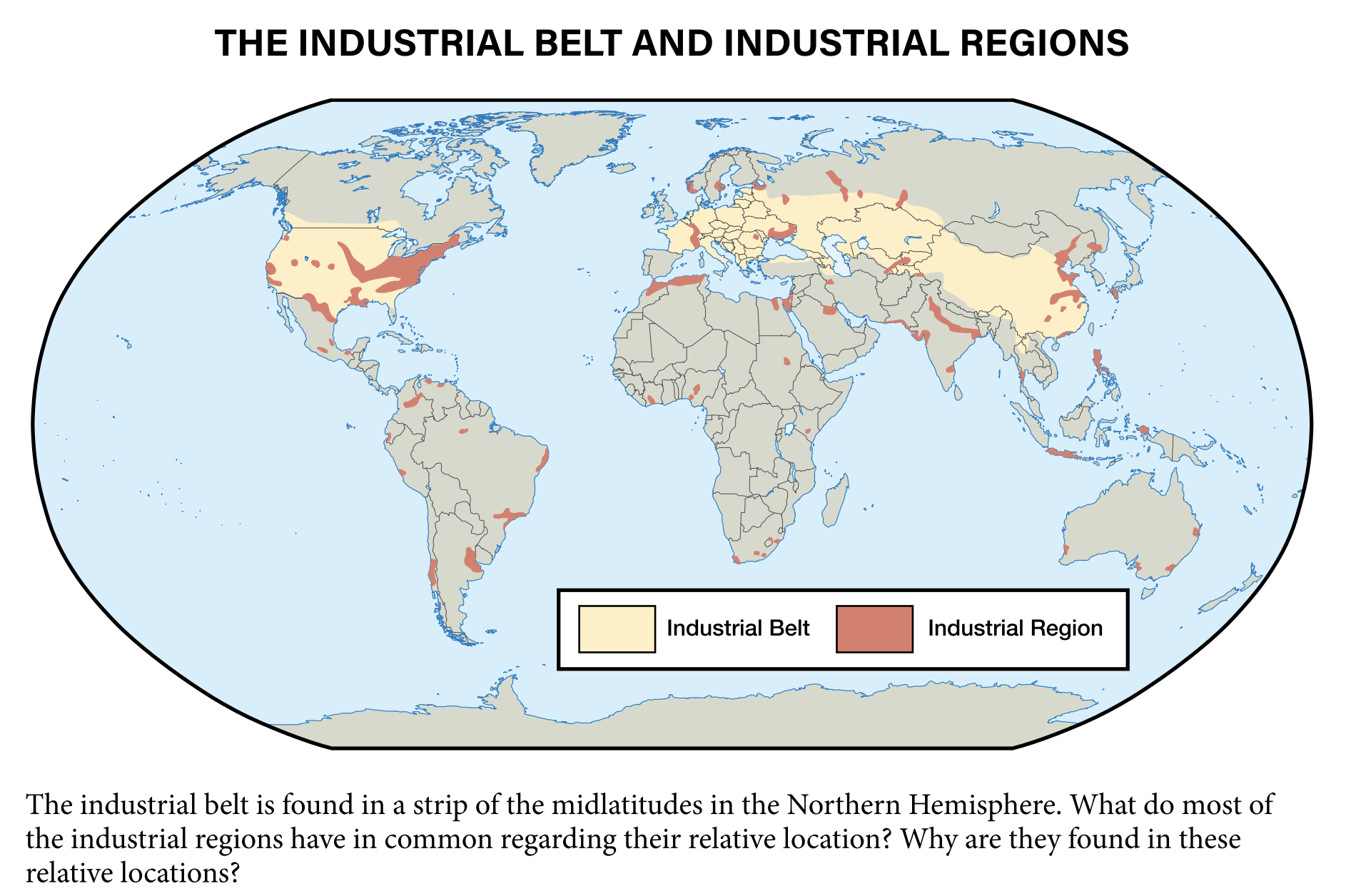

For most of the 20th century, industrialized regions were often found in large urban areas that provided a significant workforce and along coasts or rivers which provided easy transportation to global markets. Most were part of an industrial belt that stretched across the midlatitudes of the Northern Hemisphere. It included the northeastern and midwestern United States, much of Europe, part of Russia, and Japan.

However, near the end of the 1900s, these areas began to deindustrialize, a process of decreasing reliance on manufacturing jobs. As a result of improved technology, companies needed fewer employees to produce the same quantity of goods. Further, manufacturing companies transferred production to semiperiphery countries. In places such as China, India, and Mexico, companies could pay workers lower wages and avoid regulations designed to protect workers and the environment. Workers in the deindustrializing core countries fought against this process, but with limited success. Regions that have large numbers of closed factories are called rust belts.