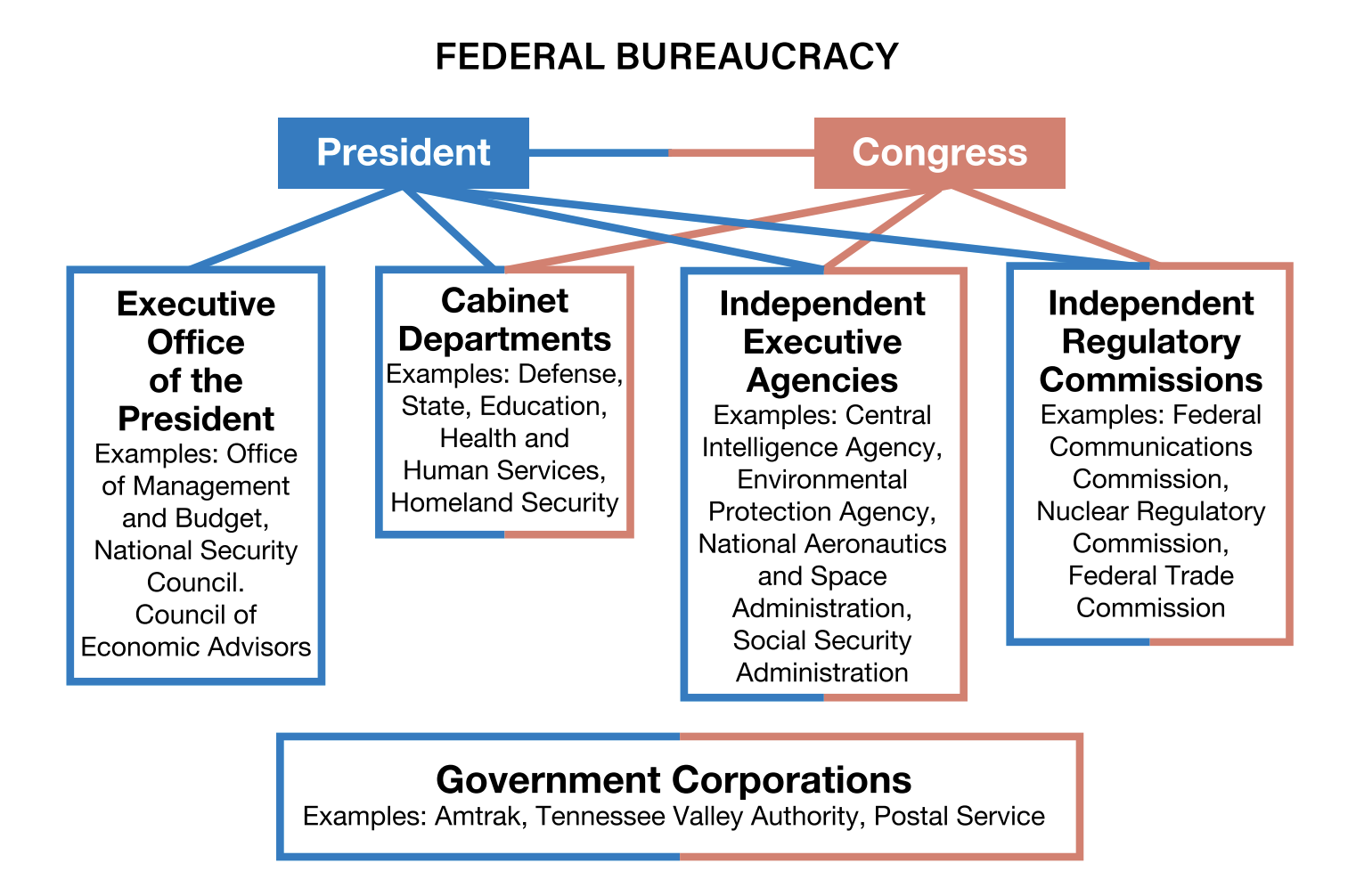

Structure:

cabinet

agencies

independent regulatory commissions

government corporation

Examples:

Homeland Security

Department of Transportation

Veteran Affairs

Department of Education

Environmental Protection Agency

Federal Elections Commission

Security & Exchange Commission

Department of State, Department of Justice

Role & Function:

rule-making

compliance monitoring

interactions with Congress

iron triangle

spoils system

civil service reform

career official vs. political appointment

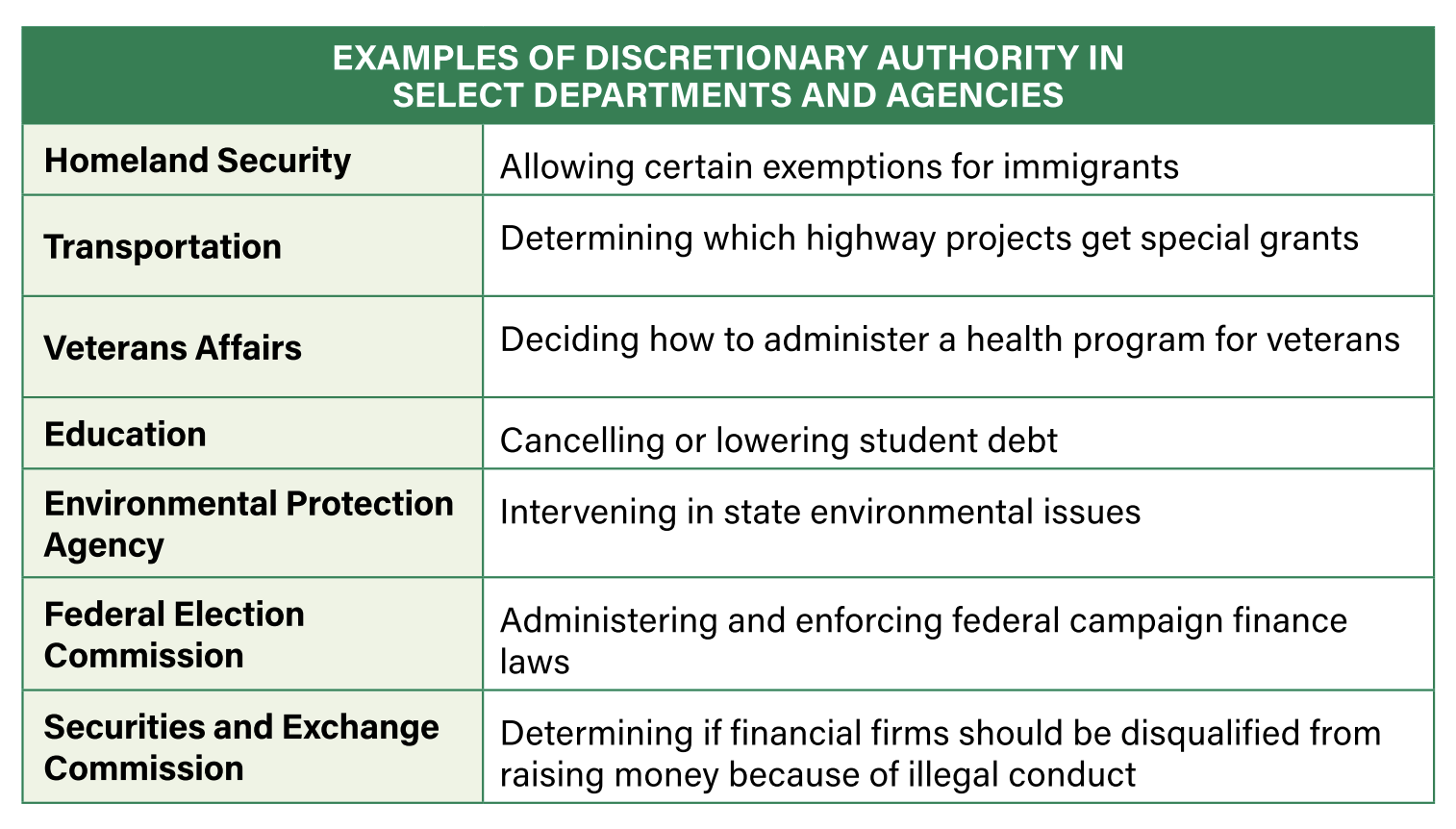

delegated discretionary authority

rule making authority

The federal government provides many services, such as maintaining interstate highways, coordinating air traffic at airports and in flight, protecting borders, enforcing laws, and delivering mail. Congress has passed a law and created one or more executive branch departments or agencies to carry out these responsibilities of government. The federal bureaucracy is the vast, hierarchical organization of executive branch employees-close to 3 million people ranging from members of the president’s Cabinet to accountants at the Internal Revenue Service-that take care of the federal government’s business.

As the nation has grown, so has the government and the bureaucracy. Federal agencies interpret, administer, and enforce the laws that Congress has passed. These responsibilities combined with administrative or bureaucratic discretion have created a powerful institution. Today’s bureaucracy is a product of 200 years of increased public expectation and increased federal responsibilities. Government professionals assure the executive agenda and congressional mandates are implemented and followed. The bureaucracy is involved in every issue of the nation and provides countless services to U.S. citizens.

Structure of the Bureaucracy

The executive hierarchy is a vast structure of governing bodies headed by professional bureaucrats. They include departments, agencies, commissions, and a handful of private-public organizations known as government corporations.

Cabinet Secretaries

To help manage the bureaucracy, presidents today appoint more than 2,000 upper-level management positions, deputy secretaries, and bureau chiefs; many of these appointments require Senate confirmation. Most of these people tend to be in the president’s party and have experience in a relevant field of government or the private sector.

President John F. Kennedy named his brother, Robert, as the nation’s attorney general.

President Barack Obama brought with him the Chicago superintendent of schools to serve as his secretary of education.

President Donald Trump named fellow New York financiers and Wall Street moguls to direct economic agencies.

Departments

The president oversees the executive branch through a structured system of 15 departments. Newer departments include Energy, Veterans Affairs, and Homeland Security. Departments have been renamed and divided into multiple departments. The largest department is by far the Department of Defense.

Each Cabinet secretary directs a department. Though different secretaries handle different areas of jurisdictions, and surely have different pressures and face different issues, they are all paid the same salary.

Agencies

The departments contain agencies that divide the departments’ goals and workload. In addition to the term agency, these subunits may be referred to as divisions, bureaus, offices, services, administrations, and boards. The Department of Homeland Security houses the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the Coast Guard, and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). These agencies deal with protecting the country and its citizens. There are hundreds of agencies, many of which have headquarters in Washington, DC, as well as regional offices in large U.S. cities.

The president appoints the head of each agency, typically referred to as the “director.” Most directors serve under a president during a four- or eight-year term. Some serve longer terms as defined in the statute that creates the agency.

The FBI is a law enforcement agency. Additional agencies fill the bureaucracy-embassies and ambassadors work within the State Department and tax collectors at the Internal Revenue Service work under the umbrella of the Treasury Department. Independent agencies, such as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), are also in the executive branch bureaucracy, but they are not connected to a department. Congress has structured these in this way to avoid undue influence from a department.

The much more complicated independent regulatory agencies can create policies with the enforcement of law for unique industries or jurisdictions. (See Topic 2.13.)

Commissions and Government Corporations

Cabinet agencies and executive agencies have one head. Independent commissions have a body (board) that consists of five to seven members.

Members of these boards and commissions have staggered terms to ensure that a president cannot completely replace them with his own cronies. For example, if the Federal Reserve Board was composed of members appointed by one president, they could boost re-election chances by manipulating the interest rate and artificially stimulating the economy as an election nears. Such an action would make the agencies and commissions political rather than neutral.

Government corporations are a hybrid of a government agency and a private company. These started to appear in the 1930s, and they are usually created when the government wants to overlap with the private sector.

Tasks Performed by the Bureaucracy

When Congress creates departments and agencies, it defines the organization’s mission and empowers it to carry out the mission. The legislature gives the departments broad goals, as they administer several agencies and a large number of bureaucrats within those departments. Agencies have more specific goals, and independent regulatory agencies have even more specialized responsibilities in their administrative mission.

Writing and Enforcing Regulations

The legislation that creates and defines the departments and agencies often gives wide latitude as to how bureaucrats administer the law. Though all executive branch organizations have a degree of discretion in how they carry out the law, the independent regulatory agencies and commissions have greater leeway and power to shape and enforce national policies than the others.

Take, for example, the chief passage from the 1970 Clean Water Act that charged the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to enforce it, “The nation’s waters should be free of pollutants in order to protect the health of our citizens and preserve natural habitats. Individuals or companies shall not pollute the nations water. If they do, they will be fined or jailed in accordance with the law. The EPA shall set pollution standards and shall have the authority to make rules necessary to carry out this Act.”

Few of the 535 legislators who helped pass this act are experts in the environmental sciences. So they delegated this authority to the EPA and keep in contact with the agency to assure that this mission is accomplished.

Enforcement and Fines

Like a court, the regulatory agencies, commission, and boards within the bureaucracy can impose fines or other punishments. This administrative adjudication targets industries or companies, not individual citizens. For example, the federal government collected civil penalties paid in connection with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill ranging from about $400 million in fiscal year 2013 to about $160 million in fiscal year 2016.

One key aspect of enforcement is compliance monitoring, making sure the firms and companies that are subject to industry regulations are following those standards and provisions. (See Topic 2.14 for more on compliance monitoring.)

Testifying Before Congress

Cabinet secretaries and agency directors are often experts in their field. For this reason, they frequently appear before congressional committees to provide expert testimony. For example, former FBI Director James Comey testified before the Senate Intelligence Committee in June 2017 about matters related to his bureau’s investigation into Russian interference in the presidential election of 2016. In September 2017, Deputy Secretary of State John L. Sullivan testified before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs to discuss a redesign of the State Department. The Secretary of Veterans Affairs, the Honorable David J. Shulkin, M.D., testified before the Senate Veterans Affairs Committee in the same month to address the problem of suicide among veterans.

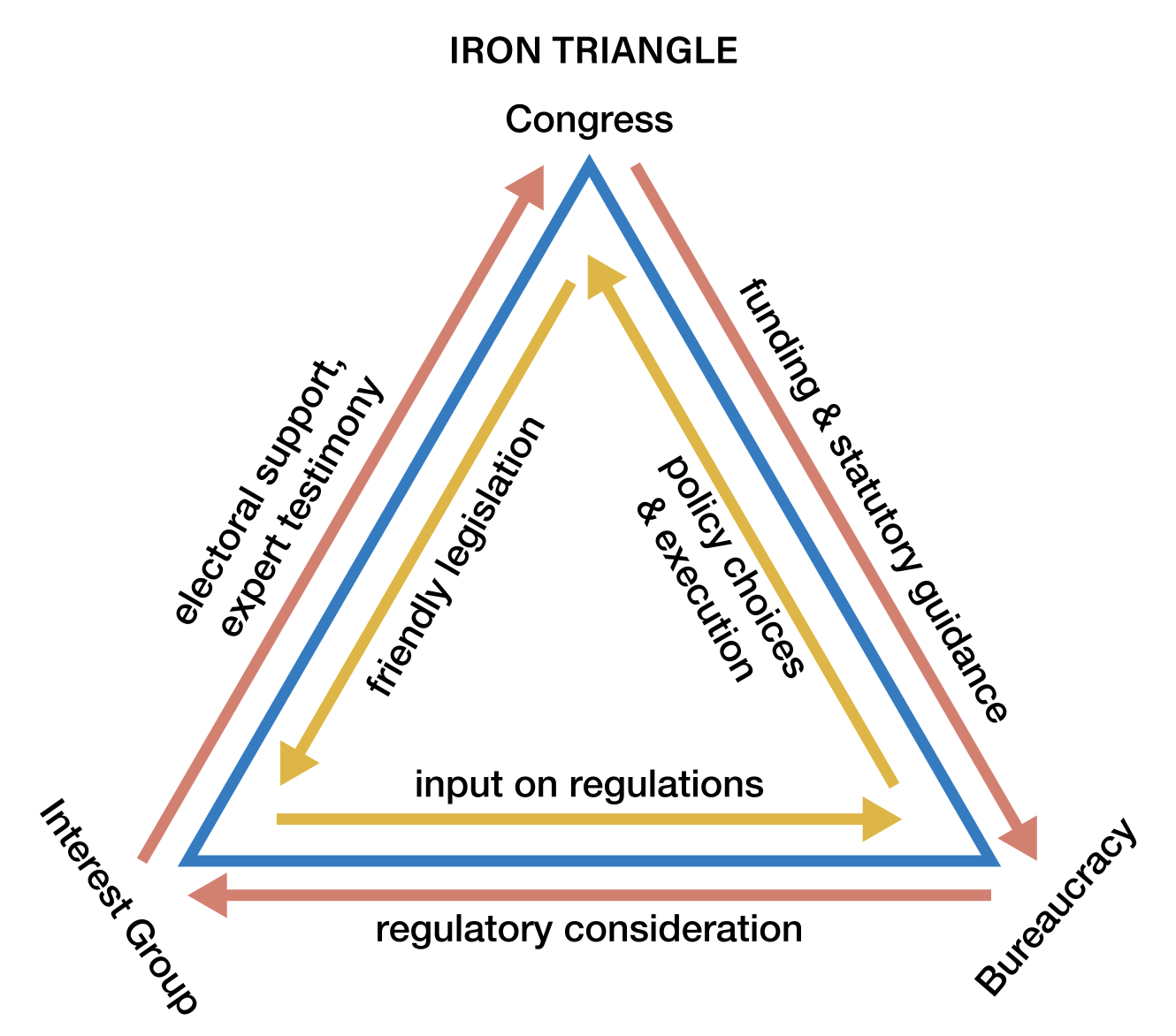

Iron Triangles and Issue Networks

Over time, congressional committees and agencies become well acquainted. Members of Congress and their staffs work with and rely upon the expert advice and information provided by the bureaucracy. In addition, lawmakers and leadership in the executive branch may have worked together in the past.

At the same time, interest groups press their agendas with relevant federal agencies. Industry can also create political action committees (PACs) to impact policy and its success. These special interests meet with and make donations to members of Congress as elections near. (See Topic 5.6.) They also meet with bureaucrats during the rule-making process (see Topic 2.13) in an ongoing effort to shape rules that affect them.

The relationship among these three entities-an agency, a congressional committee, and an interest group- is called an iron triangle because the three-way interdependent relationships are so strong. The three points of the triangle join forces to create policy. Iron triangles establish tight relationships that are often collectively beneficial. Bureaucrats have an incentive to cooperate with congressional members who fund and oversee their agencies. Committee members have an incentive to pay attention to interest groups that can provide policy information and reward them with PAC donations. Interest groups and agencies generally are out to advance similar goals from the start. However, at times iron triangles are criticized for those goals when they are exclusively for the benefit of special interest and not for the common good.

Recently, scholars have observed the power and influence of issue networks. Issue networks include committee staffers (often the experts and real authors of legislation), academics, advocates, leaders of think tanks, interest groups, and/or the media. These experts and stakeholders-sometimes at odds with one another on matters unrelated to the issue they are addressing-collaborate to create specific policy on one issue. The policymaking web has grown because of so many overlapping issues, the proliferation of interest groups, and the influence of industry.

From Patronage to Merit

For the bureaucracy to do its job well, federal employees need to be professional, specialized, and politically neutral. Reforms over the years have helped create an environment in which those goals can be achieved.

The Spoils System

In the early days of the nation, the bureaucracy became a place to reward loyal party leaders with federal jobs, a practice known as patronage. Jefferson filled every vacancy with members of his party. As presidents of different parties came and went, this “rotation system” continued regardless of merit or performance of appointees. On Andrew Jackson’s Inauguration Day in 1829, job-hungry mobs pushed into the White House, aggressively seeking patronage jobs. Congressmen began recommending fellow party members, and senators-with advice and consent power-asserted their influence on the process.

Presidents appointed regional and local postmasters in the many branch offices across the nation expecting loyalty in return. This type of patronage system, which came to be known as the spoils system, made the U.S. Post Office one of the main agencies to run party machinery.

By the end of the Civil War, the spoils system, with ample opportunities for government corruption, was thoroughly entrenched in state and federal politics.

Civil Service Reform

The desire for the best government rather than a government of friends and family became a chief concern among certain groups and associations. Moral-based movements such as emancipation, temperance, and women’s suffrage also encouraged taming or dismantling the spoils system. Reformers called for candidate appointments based on merit, skill, and experience.

In 1870, Congress passed a law that authorized the president to create rules and regulations for a civil service. Support for this reform gradually faded, however, until a murder of national consequence brought attention back to the issue. Soon after James Garfield was sworn in as president in 1881, an eccentric named Charles Guiteau began insisting Garfield appoint him to a political office. Garfield denied his requests. On July 2, only three months into the president’s term, Guiteau shot Garfield twice as he was about to board a train. Garfield lay wounded for months before he finally died.

Garfield’s assassination brought attention to the extreme cases of patronage and encouraged more comprehensive legislation. Congress passed the Pendleton Civil Service Act in 1883 to prevent the constant reward to loyal party members. The law ultimately created the merit system, which included competitive, written exams for many job applicants. The law also created a bipartisan Civil Service Commission to oversee the process and prevented officials from requiring federal employees to contribute to political campaigns.

The establishment of the civil service and an attempt by the U.S. government during the Industrial Era (1876-1900) to regulate the economy and care for the needy brought about the modern administrative state. The bureaucratic system became stocked with qualified experts dedicated to their federal jobs.

In 1887, the government created its first regulatory commission, the Interstate Commerce Commission, to enforce federal law regarding train travel and products traveling across state lines. The Pure Food and Drug Act (1906) brought attention to the meatpacking industry and other food industries, and thus, agencies were created to address these concerns. The Sixteenth Amendment (1913), which gave Congress the power to collect taxes on income, put more money into Treasury coffers, which helped the federal bureaucracy expand.

Improving the Effectiveness of the Bureaucracy

Efforts to make the bureaucracy a more professional and efficient institution of the government continued into the 20th century. President Carter promised, and delivered, reforms to the federal bureaucracy. The Civil Service Reform Act (1978) altered how a bureaucrat is dismissed, limited preferences for veterans in hopes of balancing the genders in federal employment, and put upper-level appointments back into the president’s hands. It also promoted merit and performance among bureaucrats while giving the president more power to move those not performing their jobs successfully.

The Civil Service Commission established by the Pendleton Act operated until the 1978 reforms replaced it with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). The OPM runs the merit system and coordinates the federal application process for jobs and hiring. The OPM’s goals include promoting the ideals of public service, finding the best people for federal jobs, and preserving merit system principles. Many of the larger, more established agencies do their own hiring.

In 1993, President Clinton announced a six-month review of the federal government. The National Performance Review (NPR) became Clinton’s key document in assessing the federal bureaucracy. The review was organized to identify problems and offer solutions and ideas for government savings. The group focused on diminishing the paperwork burden and placing more discretionary responsibility with the agencies. The report made almost 400 recommendations designed to cut inefficiency, put customers first, empower employees, and produce better and less-expensive government. One report, “From Red Tape to Results,” characterized the federal government as an industrial-era structure operating in an information age. The bureaucracy had become so inundated with rules and procedures that it could not perform the way Congress had intended.

Discretionary and Rule-Making Authority

There are 15 executive departments functioning in the United States and many more agencies and commissions working below those departments to implement policy. These departments and agencies administer laws that were created and shaped by Congress, the executive branch, and the courts. The process starts when Congress passes the initial law to create and define the mission and jurisdiction of the executive branch department, commission, or board. The president appoints and often directs the heads of these departments. He or she will issue executive orders and directives that shape how the agencies carry out their mission. Significant agency decisions and procedures can be contested in court. So every court opinion on an agency’s power or the fairness of its procedures can have an impact on how the department or agency operates.

Delegated Discretionary Authority

The constitutional basis for bureaucratic departments or agencies stems from Congress’s authority to create and empower them. Congress also guides and funds them. However, Congress leaves the specific regulations for implementing the policy up to the members of the bureaucracy. They allow delegated discretionary authority—the power to interpret legislation and create rules—to executive departments and agencies. Congress has granted departments, agencies, bureaus, and commissions—staffed with experts in their field—varying degrees of discretion in developing their own rules and regulations required to implement sometimes vague legislation. Sometimes the laws are so vague that it is not even clear that authority has been delegated to an agency. In some cases, the agency can simply claim broad authority. Interpreting the vagueness of the Clean Air Act, for example, the Environmental Protection Agency has claimed vast authority over regulation of greenhouse gases. The Act provides no detail of EPA authority over these pollutants and contains no mention of greenhouse gases. Yet the EPA asserted its discretionary authority to develop regulations.

Rule-Making Process

Bureaucratic agencies continually survey their responsibilities and periodically create new rules and refine old ones. However, an outcry of support from the citizenry to handle an issue or address a societal danger could cause an agency to take action on devising new rules. New technologies also affect the way an agency must enforce a rule, and new technologies can bring about new rules entirely. For example, the Federal Elections Commission is in the process of addressing Facebook and other political advertising on the Internet much as it has addressed television advertising in the past. Occasionally, agencies with overlapping jurisdictions might suggest or request that a related organization craft rules to encourage efficiency or improve communication to better enforce their common area of law.

A Transparent and Public Process

If an agency determines new rules are needed, it would closely study the issue and the basics of the rule to some degree before seeking public response. Agency officials meet with experts, research the problem themselves, and may even engage industry officials, lobbyists, or citizens who might be subjects of the proposed regulations.

The Administrative Procedures Act

Bureaucratic agencies continually survey their responsibilities and periodically create new rules and refine old ones. However, an outcry of support from the citizenry to handle an issue or address a societal danger could cause an agency to take action on devising new rules. New technologies also affect the way an agency must enforce a rule, and new technologies can bring about new rules entirely. For example, the Federal Elections Commission is in the process of addressing Facebook and other political advertising on the Internet much as it has addressed television advertising in the past. Occasionally, agencies with overlapping jurisdictions might suggest or request that a related organization craft rules to encourage efficiency or improve communication to better enforce their common area of law.

A Transparent and Public Process

If an agency determines new rules are needed, it would closely study the issue and the basics of the rule to some degree before seeking public response.

Agency officials meet with experts, research the problem themselves, and may even engage industry officials, lobbyists, or citizens who might be subjects of the proposed regulations.

The Administrative Procedures Act

The bureaucratic rule-making process has been formalized to make it fair and transparent. It is largely governed by the Administrative Procedures Act (APA), which Congress passed in 1946.

The law guides agencies in developing their rules and procedures and assures that those citizens and industries affected by a policy can have input into shaping it, providing one of many access points for stakeholders to promote their interests.

Some congressional statutes require agencies to hold rule-making hearings.

Others choose to hold public meetings to collect more information or to help inform the stakeholders or the affected groups of the proposed rule. Some agencies use webcasts and interactive Internet sessions to acquire more diverse input, a procedure many regard as democratic.

Congressional Responsibility in Rule Making

How responsible is Congress once the agency is operational and how much do they leave to the executive branch? To what extent does the process of handing off this responsibility undermine accountability to citizen-voters’ desires on these issues? Scholars Justin Fox and Stuart Jordan have examined the degree to which politically elected Congress members choose to delegate authority to the bureaucracy. ‘They found that for elected Congress members, three conditions must exist for a noticeable increase of this delegation of authority.

. Politicians must have access to much more information, and more technical information, than voters about the issue and bureaucratic actions.

- The bureaucrats must be policy experts, highly reliable and knowledgeable so they can support decisions presumed to be harmful to politicians’ constituents.

- Politicians’ electoral motives must be circumscribed to their policy motives. In other words, they care about fixing the problem more than they care about their personal approval rating.

Scholars differ, however, on how much Congress delegates discretionary authority to the bureaucracy and what effects this has. Politicians see pros and cons to the level of discretionary authority they might extend. Congress members may see a need to enact unpopular regulations, while they do not want the blame for the particulars of that regulation. For example, they might prefer bureaucrats to determine and administer fines to citizens for unpaid back taxes or closing a local factory for one too many safety violations. Being able to point to the bureaucracy for such a harsh policy might divert some resentment at election time.

Implementing the Law

Depending on its discretionary authority, any executive branch agency may have the power to make decisions and to take, or not take, a course of action. Congress has given the executive branch significant authority in three ways, by (1) creating agencies to pay subsidies to groups, such as farmers or Social Security recipients;

(2) creating a system to distribute federal dollars going to the states, such as grant programs (see Topic 1.7); (3) and giving many federal offices the ability to devise and enforce regulations for various industries or issues. This quasi-legislative power enables departments and agencies to determine law. For example, the Federal Communications Commission can identify what is indecent for televised broadcasts and the EPA can define factory emission standards.

Due to the complexity of final rules or regulations, agencies are required to publish information about what is being implemented. This information will often consist of an introduction and official summary of the societal problem (s) and the regulatory goal that justifies the rule is required. The agency must identify its legal authority to create and enforce such a rule and publish the regulatory text in full. All new regulations must also list an effective date. Most finalized regulations must allow for a grace period, usually 30 days, sometimes as long as 180, before they can go into effect. A final printing of the law is placed in the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations. The Federal Register prints the record of how the regulation started, how it was developed, and how it landed in its final form. The Code more cleanly arranges the final regulation or law.

Independent Regulatory Agencies

Independent regulatory agencies and commissions have unique charges from Congress to enforce or regulate industry-specific law. These entities can create industry-specific regulations and issue fines and other punishments. Some are structured with a director and assistants, and some are headed by a board or commission led by a chairperson, such as the Federal Elections Commission.

Members of these boards and commissions have staggered terms to ensure that a president cannot completely replace them with his own chosen appointees. Directors of such groups are appointed by a president but cannot be easily removed. In fact, a president can only remove these executives if the president shows cause.

The president might recommend or work with a regulatory agency in designing new rules but probably has less influence on them than other departments and agencies. He would certainly have less influence on the implementation and enforcement of such rules.

Perhaps more familiar are the rules established by the Transportation Security Administration, the agency in the Department of Homeland Security that monitors passengers boarding airplanes. Who will be searched and how?

These procedures change from time to time as the government finds new reasons to ban certain items from flights or to soften an overly strict list. The chief lawmaking body, Congress, with its complex lawmaking procedures and necessary debates, cannot keep up with the day-to-day changes in policies and procedures so it entrusts the TSA to monitor the airlines and empowers it to make rules to keep passengers safe.

The powers delegated to these regulatory agencies can change over time.

The powers of the Federal Election Commission have been under fire recently.

The authority of the FEC has been in question since the Citizens United v. FEC (2010) and McCutcheon v. FEC (2014) decisions opened up campaign contributions. Many argue that the agency still has the rule-making power to tighten up the regulations on campaign finance even after the Court’s decisions, but weak leadership has stymied any efforts. Additionally, the 2019 resignation of another member of the Commission has left the agency short of the required four-person quorum. Until a new appointee is approved, the Federal Election Commission cannot perform some important functions, such as issuing fines for violations, conducting audits, or initiating investigations.