Formal Powers:

veto (and the pocket veto)

commander of the armed forces

Congressional Advise & Consent:

ambassadors

cabinet members

federal court appointments (judges)

Informal Powers:

power of persuasion (more in next chapter)

executive order

signing statement

executive agreement

The American presidency comes with ceremony, custom, and expectation.

Presidential institutions, such as the White House, Air Force One, and the State of the Union address, are likely familiar to you. Signing ceremonies and photo opportunities with foreign dignitaries are common images. The Constitution lays out the president’s job description in broad language. The president has both formal and informal powers and functions to accomplish a policy agenda, a set of issues that are significant to people involved in policymaking.

The American presidency, visible on a world scale, is an iconic and powerful institution that has become much more influential over time. Presidents administer the law through a large bureaucracy of law enforcement, military, trade, and financial agencies. Chief executives meet with world leaders, design the national budget, and campaign for their party’s candidates.

Framers’ Vision

The delegates in Philadelphia in 1787 voted to make the presidency an executive office for one person. Fears arose because skeptics saw this office as a potential “fetus of monarchy.” One delegate tried to allay such fears, explaining:

“it will not be too strong to say that the station will probably be filled by men preeminent for their ability and virtue.”

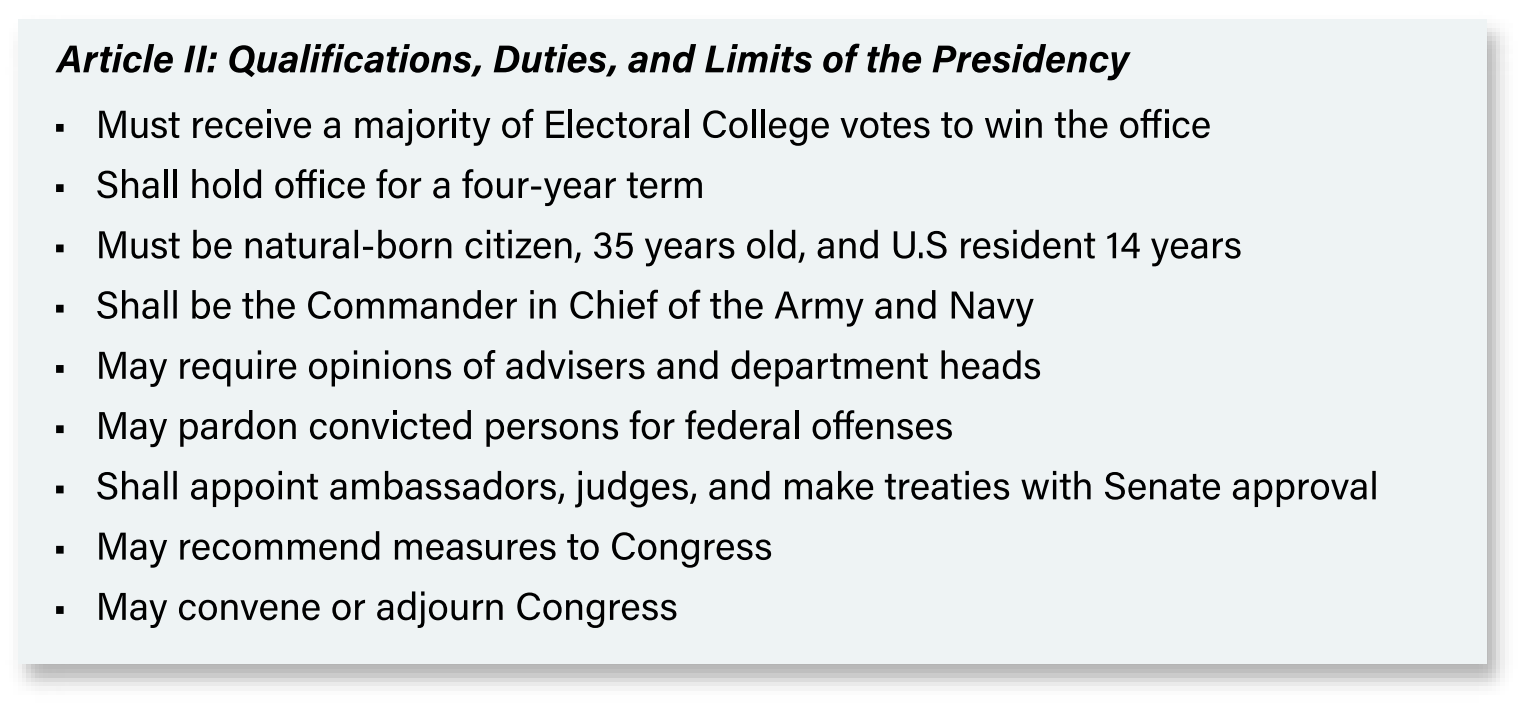

Article Il

The Constitution requires the president to be a natural-born citizen, at least 35 years old, and a U.S. resident for at least 14 years before taking office. The president is the Commander in Chief and also has the power to issue pardons and reprieves, and to appoint ambassadors, judges, and other public ministers.

The president can recommend legislative measures to Congress, veto or approve proposed bills (from Article I), and convene or adjourn the houses of Congress. The framers also created a system by which the Electoral College chooses the president every four years.

Presidential Powers, Functions, and Policy Agenda

The president has many powers and functions that enable him to carry out the policy agenda he laid out during the campaign. The president exercises the formal powers of the office, those defined in Article II, as well as the informal powers, those political powers interpreted to be inherent in the office, to achieve policy goals. Congress and the Supreme Court have bestowed additional duties and placed limits on the presidency.

Formal and Informal Powers

A president cannot introduce legislation on the House or Senate floor but in many ways still serves as the nation’s chief lawmaker. Article II also gives the president the power to convene or adjourn Congress at times. As the head of state, the president becomes the nation’s chief ambassador and the public face of the country. As Commander in Chief, the president manages the military.

Running a federal bureaucracy that resembles a corporation with nearly three million employees, the president is a CEO. And finally, as the de facto head of the party, the president becomes the most identifiable and influential Republican or Democrat in the country.

Chief Legislator

The Constitution provides that the president “may recommend [to Congress] such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” Presidents may recommend new laws in public appearances and in their State of the Union address or at other events, pushing Congress to pass their proposals. Congress often leaves this proactive approach to policy leadership to the president rather than taking it upon itself. Presidents have asked Congress to pass laws to clean up air and water, amend the Constitution, create a national health care system, and declare war. A president with a strong personality can serve as the point person and carry out a vision for the country more easily than any or all of the 535 members of Congress.

Powers of Persuasion

The president uses a number of skills to win support for a policy agenda. The president will use bargaining and persuasion in an attempt to get Congress to agree with and pass the legislative agenda. President Trump’s most notable bill to pass Congress in his first year was a major tax overhaul that reduced corporate taxes from 35 to 21 percent and changed federal income tax rates, lowering them, at least temporarily, for a vast majority of citizens. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act passed only after Trump, a real estate developer, used his skills as a salesman to push for it. As Politico reported, “He has spent weeks wooing, prodding, cajoling and personally calling Republican lawmakers to pass sweeping tax legislation in time for Christmas. He closed on this tax bill as he would have closed a real estate deal decades ago, with a hard and convincing sell. Using his informal political powers, Trump personally called the wavering members of the Senate.”

Veto

The president has the final stamp of approval of congressional bills and also a chance to reject them with the executive veto. After a bill passes both the House and the Senate, the president has ten days (not including Sundays) to sign it into law. If vetoed, “He shall return it, the Constitution states, “with his objections to the House in which it shall have originated.” This provision creates a dialogue between the two branches, enables Congress to consider the president’s critique, and encourages consensus policies.

At times, a president will threaten a veto, exercising an informal power that may supersede the formal process. When disagreements between the president and his party or the majority of Congress over the details of a new law exist, the president may threaten to veto, conditionally, if the bill is not satisfactory.

Congressional proponents of a bill will work cooperatively to pass it, reshaping it if necessary, to avoid the veto.

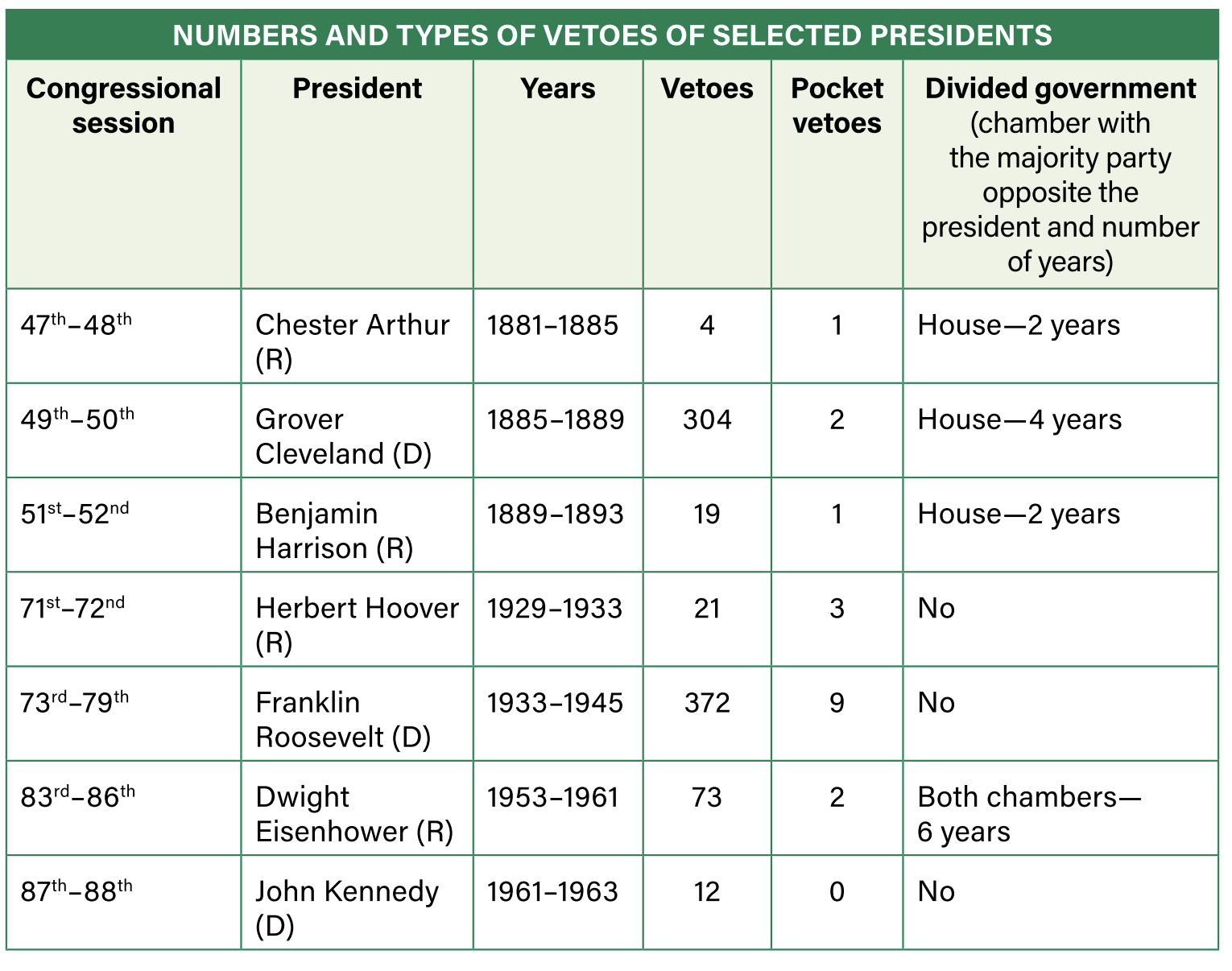

The use of the veto has fluctuated throughout presidential history. When there is a divided government-one party dominating Congress and another controlling the presidency- there is usually a corresponding increase in vetoes.

The last three presidents, at times, each served with divided governments during their eight years as president. Democrat Bill Clinton had 37 vetoes;

Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Barack Obama each had 12.

The president can opt to neither sign nor veto. Any bill not signed or vetoed becomes law after the ten-day period. However, if a president receives a bill in the final ten days of a congressional session and does nothing, this pocket veto allows the bill to die.

Congress can override a presidential veto if two-thirds of each house approves the bill. Reaching the two-thirds threshold is very challenging and fewer than 10 percent of a president’s vetoes are overridden.

Line-Item Veto

Since the founding, presidents have argued for the right to a line-item veto. This measure would empower an executive to eliminate a line of spending from an appropriations bill or a budgeting measure, allowing the president to veto part, but not all, of the bill. Many state governors have the line-item veto power. In 1996, Congress granted this power to the president for appropriations, or new direct spending, and limited tax benefits. Unlike a Congress member, the president has no loyalties to a particular congressional district and can thus sometimes make politically difficult local spending cuts without concern for losing much regional or national support.

Under the new act, President Clinton cut proposed federal monies earmarked for New York City. The city sued, arguing that the Constitution gave Congress the power of the purse as an enumerated congressional power, and New York City believed this new law suddenly shifted that power to the president. The Court agreed that the only way to give the president this power would be through a constitutional amendment and struck down the act in Clinton v. City of New York (1998). Presidents and fiscal conservatives continue to call for a line-item veto to reduce spending. There is little doubt that such power would reduce at least some federal spending. However, few lawmakers (who can currently send pork barrel funds to their own districts) are willing to provide the president with the authority to take away that perk.

Commander in Chief

The framers named the president the Commander in Chief with much control over the military. The Constitution, however, left the decision of declaring war solely to the Congress. The question of what constitutes a war, though, is not always clear.

Senator Barry Goldwater proclaimed in the waning days of the Vietnam conflict, “We have only been in five declared wars out of over 150 that we have fought.” His point was fair, although his estimate was debatable. The issue remains: Should all troop landings be considered wars that therefore require congressional declarations?

When a military operation is defensive, in response to a threat to or attack on the United States, the executive can act quickly. FDR ordered U.S. troops to Greenland in 1940 after the Nazis marched into Denmark but before any U.S. declaration of war. President Clinton bombed Iraq after discovering the failed assassination attempt on his predecessor, the elder President Bush. President Obama authorized the U.S. mission in 2011 to capture or kill Osama bin Laden, the al-Qaeda founder responsible for the September 11, 2001, attacks. A U.S. Navy Seal team was on the ground in Pakistan for only about 40 minutes. Some believe that actions such as these stretch the meaning of “defensive” too far. Yet how successful would this mission have been if Congress had to debate publicly and vote in advance on whether or not to invade the unwilling country that harbored bin Laden?

The Cold War era greatly expanded the president’s authority as Commander in Chief. In the early 1960s, one senator conceded that the president must have some war powers because “the difference between safety and cataclysm can be a matter of hours or even minutes.” The theory of a strong defense against “imminent” attack has obliterated the framers’ distinction and has added an elastic theory of defensive war to the president’s arsenal. Imminent-defense theorists argue the world was much larger in 1789, considering warfare, weaponry, and the United States’ position in the world. Today, with so many U.S. interests abroad, an attack on American interests or an ally far from U.S. shores can directly and immediately impact national security.

Chief Diplomat

Through treaties, presidents can facilitate trade, provide for mutual defense, help set international environmental standards, or prevent weapons testing, as long as the Senate approves. President Woodrow Wilson wanted the United States to join the League of Nations after World War I, but the Senate refused to ratify Wilson’s Treaty of Versailles.

An executive agreement resembles a treaty yet does not require the Senate’s two-thirds vote. It is a simple contract between two heads of state: the president and a prime minister, king, or president of another nation. Like any agreement, such a contract is only as binding as each side’s ability and willingness to fulfill the promise. To carry it out, a president will likely need cooperation from other people and institutions in the government. These compacts cannot violate prior treaties or congressional acts, and they are not binding on successive presidents.

Presidents have come to appreciate the power of the executive agreement. President Washington found conferring with the Senate during each step of a delicate negotiation extremely cumbersome and perhaps dangerous. It compromised confidentiality and created delays.

Executive agreements can ensure secrecy or speed or avoid ego clashes in the Senate. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962, President Kennedy discovered the Soviet Union’s plan to install nuclear missiles in Cuba. Intelligence reports estimated these weapons would be operational within two weeks. After days of contemplation, negotiation, and a naval standoff in the Caribbean, the United States and the Soviet Union made a deal. The agreement stated that the Soviets would remove their offensive missiles from Cuba if the United States would later remove its own missiles from Turkey.

Had Kennedy relied on two-thirds of the Senate to help him solve the crisis, a different outcome could very well have occurred. Time, strong words on the Senate floor, or an ultimate refusal could have drastically reversed this historic outcome.

Chief Executive and Administrator

How the president and his appointees enforce or implement a new law will shape the administration’s policy agenda. Using executive orders, signing statements, and running the machinery of the vast executive branch mark how a president carries out the powers and functions as the chief executive.

The Supreme Court has defined some of the gray areas of presidential power. For example, the president can fire most Senate-approved subordinates without cause.

Executive Orders

An executive order empowers the president to carry out the law or to administer the government. Unlike a criminal law or monetary appropriation, which requires Congress to act, a presidential directive falls within executive authority. For example, the president can define how the military and other departments operate.

Executive orders have the effect of law and address issues ranging from security clearances for government employees to smoking in the federal workplace. In 1942, for example, President Franklin Roosevelt (FDR) issued the infamous Executive Order 9066, which allowed persons identified by the secretary of war to be excluded from certain areas. This executive order resulted in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. In 1948, through an executive order, President Harry Truman directed the military to racially integrate. Recently, President Donald Trump issued an executive order outlining an immigration policy that limited travelers entering the United States from six countries with Muslim-majority populations. Executive orders cannot address matters under exclusive congressional jurisdiction, such as altering the tax code, creating new interstate commerce regulations, or redesigning the currency. Executive orders can also be challenged in court. The Supreme Court upheld both FDR’s wartime internment and Trump’s travel ban.

Signing Statements

Though the president cannot change the wording of a bill, several presidents have offered signing statements when signing a bill into law. These statements explain their interpretation of a bill, their understanding of what is expected of them to carry it out, or just a commentary on the law. A signing statement allows a president to say, in effect, “Here’s how I understand what I’m signing and here’s how I plan to enforce it.” Critics of the signing statement argue that it violates the basic lawmaking design and overly enhances a president’s last-minute input on a bill.

Executive Privilege

Starting with George Washington’s precedent, presidents have asserted executive privilege, the right to withhold information or their decision-making process from another branch, especially Congress. They have particularly asserted that they need not make public any advice they received from their subordinates to protect confidentiality. Presidents have also claimed that such information is privileged, protected by the separation of powers.

President Richard Nixon tested executive privilege during the Watergate scandal when Nixon and others were accused of covering up criminal actions against political rivals. Nixon refused to turn over investigator-subpoenaed tapes, alleged to reveal the president’s knowledge of the 1972 break-in at the Watergate Office Building to steal information about the Democratic Party.

Nixon declared his secretly recorded conversations were protected from congressional inquiry by executive privilege. In U.S. v. Nixon (1974), the Supreme Court did acknowledge that executive privilege is constitutional and necessary at times. Yet the Court unanimously agreed the tapes amounted to evidence in a criminal investigation and therefore were not protected by executive privilege. Nixon turned over the recordings.

Checks on the Presidency

The president’s formal powers enable him to appoint a team to execute the laws and to accomplish his policy agenda. Some of those administrators hold positions Congress created in 1789. Many more subordinate positions exist because Congress has since created them or has allotted funds for offices to support the president. A typical president will appoint thousands of executive branch officials during their tenure. Atop that list are the Cabinet officials, agency directors, military leaders and commissioned officers, and the support staff that work directly for the president. Most of these employees serve at the pleasure of the president, and some are kept on when a new president is elected.

Other positions are protected by statute or Supreme Court decisions.

The President’s Team

The president is faced with countless decisions each day and many of those decisions have exceptionally important consequences to the fate of the nation. A large team is needed to assist the president in making these decisions.

Article II, Section 2, of the Constitution gives the president the power to assemble that group and “appoint ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls … and all other officers of the United States whose appointments are not herein otherwise provided for and which shall be established by law.”

The Vice President

A political party’s presidential nominee, in consultation with the party, selects a vice president before the election. Many assume the vice president is the second most powerful governmental officer in the United States, but in reality, the vice president is an assistant to the president with little influence and a largely undefined job description. Different presidents have given their vice presidents differing degrees of authority and assigned them different roles.

The Constitution names the vice president as the president of the Senate and declares that in case of presidential removal, death, resignation, or inability, the president’s duties and powers “shall devolve on the vice president.”

Shaping and Supporting Policy

In recent years, the position of vice president has been especially influential in shaping presidential policy. For instance, Dick Cheney, serving under George W. Bush, wielded significant influence, advocating for a tough stance on terrorism and promoting the invasion of Iraq in 2003 in search of weapons of mass destruction. Joe Biden, during his tenure as vice president under Obama, also had a substantial impact, particularly in concluding the mission in Iraq and negotiating budget deals with Republican leaders in Congress. Biden was widely recognized for his influence and received accolades from President Obama as one of the best vice presidents in American history.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Vice President Mike Pence played a pivotal role when President Trump appointed him to coordinate the nation’s response. Pence relied on experts like Dr. Deborah Birx to advise on policies based on scientific predictions about the spread of the disease.

The Cabinet and Bureaucracy

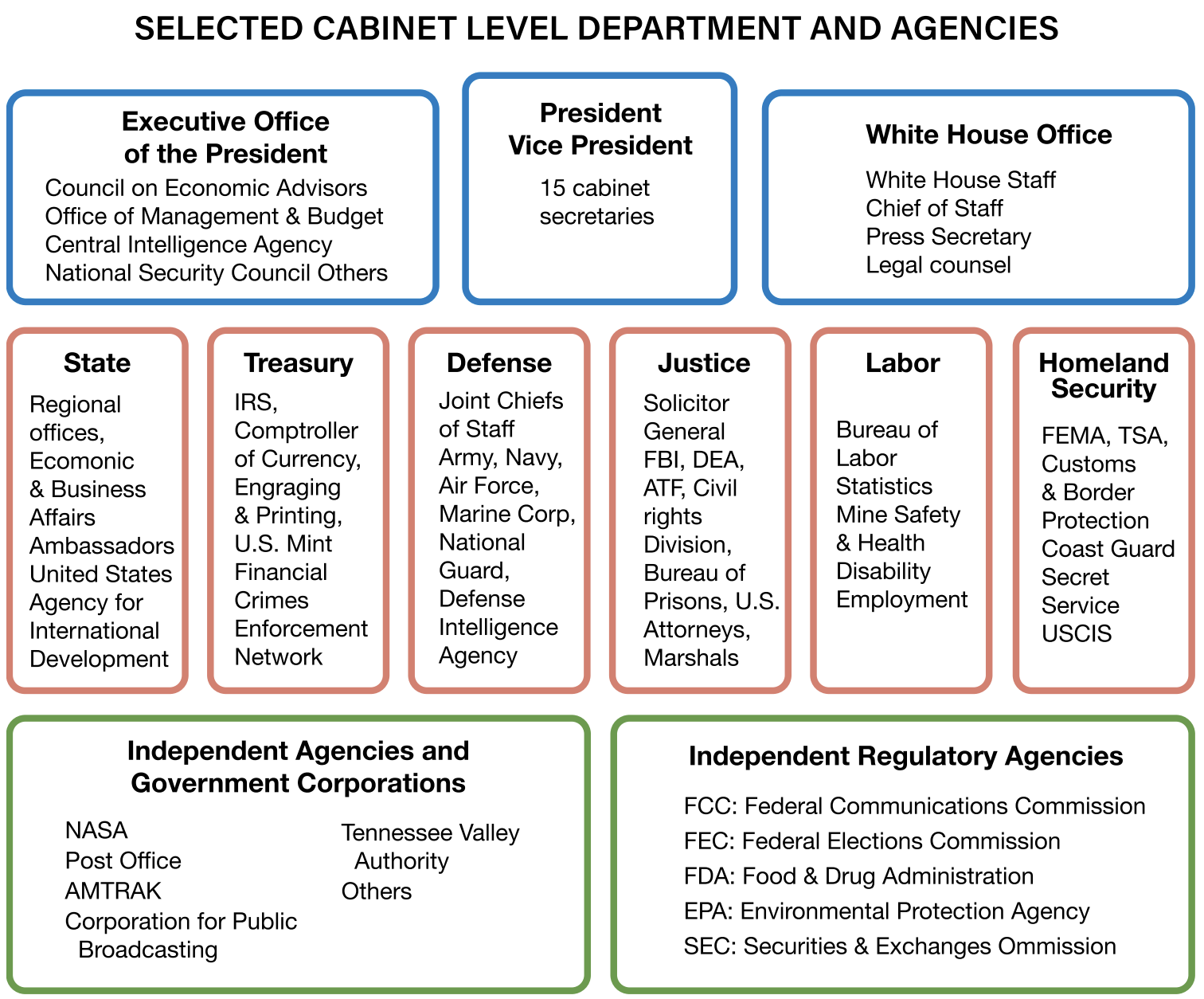

Article II of the Constitution refers to a Cabinet by mentioning “the principal officers in each of the executive departments.” Today, there are 15 Cabinet secretaries, such as the secretary of defense and secretary of transportation, who advise the president and oversee large governmental departments that handle diverse national concerns. Presidents can also appoint additional members to the Cabinet beyond the statutory departments.

When appointing Cabinet secretaries, modern presidents often consider factors like geographic representation, gender, ethnicity, and ideological balance. Showcasing diversity in appointments has been seen as beneficial for advancing presidential agendas. Historical examples include Franklin Roosevelt appointing Francis Perkins as the first woman in the Cabinet as Secretary of Labor, and Lyndon Johnson appointing Robert Weaver as the first African American Cabinet member as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

President Jimmy Carter notably increased the diversity of his senior executive appointments, appointing significant numbers of African Americans and women to cabinet positions. President Biden’s cabinet continues this trend with a diverse composition, including the appointment of Pete Buttigieg as the first openly gay Cabinet member serving as Secretary of Transportation.

The State Department, established in 1789 and initially headed by Thomas Jefferson, plays a crucial role in advancing U.S. foreign policy globally. It serves as the president’s primary diplomatic arm, overseeing relations with nearly every recognized nation worldwide. Each country with which the United States has diplomatic relations hosts a U.S. embassy staffed by an ambassador, a senior diplomat appointed to represent American interests in that country. In turn, these countries typically maintain embassies in Washington, D.C.

Ambassadors appointed by the U.S. are often career diplomats with extensive experience in foreign affairs or international experts. However, political appointees, such as former senators or prominent individuals, also serve as ambassadors to some nations, often to emphasize diplomatic priorities or relationships.

The Defense Department, headquartered at the Pentagon near Washington, D.C., oversees the nation’s military branches: the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines. Civilian secretaries of defense, who must not have served in the military for at least seven years prior to their appointment, lead the department under the president’s authority. This structure ensures civilian control over the military, distinguishing U.S. governance from military-dominated regimes found in some dictatorships.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff, comprised of top uniformed officials from each military branch, advises the president on military strategy and policy. Defense spending constitutes a significant portion of the federal budget, comprising about one-fifth of total expenditures and the largest share of discretionary spending in the U.S. budgetary framework.

Federal Agencies

Federal agencies are subcabinet entities that carry out specific government functions. Many fall under larger departments. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) -a crime fighting organization -falls under the Justice Department. The Coast Guard falls under the Department of Homeland Security. Other agencies include the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Postal Service. Thousands of people in Washington and across the country staff these few hundred executive branch agencies. They carry out laws Congress has passed with funds Congress has allotted.

President’s Immediate Staff

In 2008, 74 separate policy offices and 6,574 total employees worked for the president (most not working in the White House). Ideally, all of the offices and agencies play a part in implementing the president’s policy goals.

Executive Office of the President (OP)

The Executive Office of the President (OP) operates within walking distance of the White House. It coordinates several independent agencies that carry out presidential duties and handle the budget, the economy, and staffing across the bureaucracy. Created in 1939 when FDR needed an expanded presidential staff, the EOP now includes the Office of Management and Budget, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Council of Economic Advisers, and other agencies.

White House Staff

The president’s immediate staff of specialists make up the White House Office. These staffers require no Senate approval and tend to come from the president’s inner circle or campaign team. They generally operate in the West Wing of the building. Presidents sometimes come to rely on their White House staffs more than their Cabinet or agency heads because staff members serve the president directly. Unlike secretaries, they do not have loyalties to departments or agencies and do not compete for funding. The staff interacts and travels with the president daily and many staffers have worked with prior presidents. A staffer’s individual relationship with and access to the president will determine his or her influence.

National Security Adviser

In the 1950s, President Eisenhower’s chief of staff became his gatekeeper, responsible for the smooth operation of the White House and the swift and accurate flow of business, paper, and information. Though the chief of staff has no official policymaking power, a president seeks the chief of staff’s opinion on many issues, giving the position a great deal of influence. Chiefs of staff tend to be tough, punctual, detail-oriented managers, and these qualities allow the president to concentrate on big-picture decisions. Ron Klain served as chief of staff for then- Vice President Joe Biden and served in that role again after Biden became president.

The remainder of the president’s inner circle includes the top communicator to the people, the White House press secretary; the president’s chief legal counsel; and his national security adviser. The national security adviser coordinates information coming to the president from the CIA, the military, and the State Department to assess any security threat to the United States. This person heads the National Security Council that includes the president, secretaries of defense and state, top intelligence and uniformed military leaders, and a few others.

Interactions with Other Branches

Since Congress writes most law, holds the federal purse, and confirms presidential appointments, presidents must stay in good graces with representatives and senators. The president’s agenda is not always Congress’s agenda, however, and tensions often arise between the branches. As chief legislator, the president directs the Office of Legislative Affairs to draft bills and assist the legislative process. Sometimes the aides employ techniques to push public opinion in a lawmaker’s home district in the direction of a desired presidential policy so that the lawmaker’s constituency can apply pressure. As the president enforces or administers the law, the courts determine if laws are broken, misapplied, or unjust. For these reasons, a president regularly interacts with the legislative and judicial branches.

Checks on Presidential Powers

The framers took seriously the concerns of the Anti-Federalists and included specific roles and several provisions to limit the powers of the future strong, singular leader.

‘The Senate has the power to provide advice and consent on appointments, for example, and the presidential salary is set by Congress and cannot increase or decrease during the elected term. The framers also expressly made the president subject to impeachment.

While some presidential powers, such as serving as Commander in Chief, appointing judges and ambassadors, and vetoing legislation, are explicit, presidents and scholars have argued about the gray areas of a president’s job description. Most presidents have claimed inherent powers, those that may not be explicitly listed but are nonetheless within the jurisdiction of the executive. This debate has taken place during nearly every administration when an emergency has arisen or when the Constitution doesn’t specifically address an emerging issue. Presidents have fought battles for expanded powers, winning some and losing others. The debate continues today.

The Senate and Presidential Appointees

In addition to the more visible Cabinet appointees, a president will appoint approximately 65,000 military leaders and about 2,000 civilian officials per two-year congressional term, most of whom are confirmed routinely, often approved en bloc, hundreds at a time. Occasionally, high-level appointees are subjected to Senate investigation and public hearing. Most are still approved, while a few will receive intense scrutiny and media attention, and some appointments will fail. Because the founders did not anticipate that Congress would convene as frequently as it does in modern times, they provided for recess appointments. If the Senate is not in session when a vacancy arises, the president can appoint a replacement who will serve until the Senate reconvenes and votes on that official. This recess appointment is particularly necessary if the appointee is to handle urgent or sensitive work. This situation is rare, especially when the government is divided. Often a pro forma, or “in form only, session will be called to ensure the Senate technically remains in session. These sessions often last only a few minutes. The Senate invariably accepts presidential Cabinet nominations. The upper house swiftly confirmed every Cabinet-level secretary until 1834, when it rejected Andrew Jackson’s appointee, Roger Taney, as secretary of the treasury over Taney’s opposition to a national bank. The makeup of the Senate changed with the next election and Jackson appointed Taney as chief justice of the Supreme Court, who was confirmed for the position by a slim margin. To date, the Senate has rejected, by vote, only nine department secretaries. The Senate usually accepts Cabinet appointees based on the reasoning that since the president won a democratic election, he should therefore have the prerogative of shaping the administration. Presidents commonly choose senators to move over to the executive branch and serve in their Cabinet. In recent ears, the president has selected one or more members of the opposite party. President Obama named three Republicans to serve as secretaries (though one declined the offer). Presidents and their transition teams do a considerable amount of vetting of potential nominees and connecting with senators to evaluate their chances before making official nominations. Though only nine nominations have been rejected by vote, 13 Cabinet appointees withdrew before the Senate voted. Additional names have been floated among senators, but they didn’t receive the support to justify the official nomination.

Senate Standoffs

The two most recent standoffs on Cabinet appointments came in 1989 and in 2017. President George H. W. Bush named former Senator John Tower as secretary of defense, and President Donald J. Trump nominated Betsy DeVos as secretary of education. Senator Tower had served in the Senate since Lyndon Johnson vacated the seat to become vice-president. Tower had the resume and experience to serve as defense secretary. He served in World War II and later as the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Upon his nomination, even Democratic Party leaders anticipated his nomination would sail through. However, allegations of heavy drinking and “womanizing” surfaced. Additionally, Tower owned stock in corporations with potential future defense contracts, an obvious conflict of interest. President Bush stuck by his former congressional colleague (Bush had represented Texas in the House). In the end, the Senate voted Tower down 53 to 47. In 2017, President Trump nominated Betsy DeVos as education secretary. Like some conservatives, she held interest in privatizing education and, if confirmed, she would pursue that agenda goal. Despite DeVos advocating for private schools for many years before her nomination, she had never worked in public schooling in any capacity, including as a teacher, and along with her billionaire husband she had invested in for-profit charter schools and pushed for online education. The educational community was generally against her nomination, with some exceptions. At her public confirmation hearing, many senators expressed concern about her priorities, her experience, and her high-dollar donations to Republican candidates. As she fielded questions before the Senate committee, her competence in the field seemed shaky. Exchanges on school choice, guns in schools, students with disabilities, and private or online school accountability raised eyebrows on Capitol Hill and in news reports that followed. In the end, two Republican senators voted against her, leaving the Senate in a dead tie. Vice President Pence’s tie-breaking vote made DeVos the secretary of education.

Ambassador Appointments

The Senate is also likely to confirm ambassador appointments, although those positions are often awarded to people who helped fund the president’s campaign rather than people well qualified for the job. On one of the “Nixon Tapes” from 1971, Nixon tells his chief of staff that “anybody who wants to be an ambassador must at least give $250,000.” About 30 percent of ambassadors are political appointees. Some may have little or no experience to qualify them, though they are rarely rejected by the Senate.

Businessman Donald Trump fired people from the reality television show ‘The Apprentice much like President Trump dismissed his appointees and shifted his underlings around. He deliberately left administrative positions empty with “acting” or temporary appointees for long periods of time. In a 2019 interview, President Trump stated, “I like acting [appointees] because I can move so quickly.” A study by Christina Kinane found that one-fourth of all acting officials between 1977 to 2019 served under President Trump, and the study concluded only midway through his presidency.

Removal

The president can remove upper-level executive branch officials at will, except those that head independent regulatory agencies.

A president’s power of removal has been the subject of debate since the writing of the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton argued that the Senate should, under its advice and consent power, have a role in the removal of appointed officials.

James Madison, however, argued that to effectively administer the government the president must retain full control of subordinates. The Article II phrase that grants the president the power to “take care that the laws be faithfully executed” suggests the president has a hierarchical authority over secretaries, ambassadors, and other administrators. This issue brought Congress and the president to a major conflict in the aftermath of the Civil War. President Andrew Johnson dismissed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, congressional Republicans argued, in violation of the Tenure of Office Act. This action led to Johnson’s impeachment.

The question of removal resurfaced in 1926. The Supreme Court concluded that presidential appointees “serve at the pleasure of the president.” The Court tightened this view a few years later when it looked at a case in which the president had fired a regulatory agency director. The Court ruled in that case that a president can dismiss the head of a regulatory bureau or commission but only upon showing cause, explaining the reason for the dismissal. The two decisions collectively define the president’s authority: executive branch appointees serve at the pleasure of the president, except regulatory heads, whom the president can remove with explanation.

Judicial Interactions

Presidents interact with the judiciary in a few ways. As the head of the executive branch, presidents enforce judicial orders. For example, when the Supreme Court ruled in 1957 that Central High had to admit nine African American students into the school, President Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock, Arkansas, to ensure the school followed the court order. The branches also interact when courts check the executive if they find presidential action unconstitutional. For example, in 1952 the Supreme Court overturned President Truman’s decision to nationalize steel industries during the Korean War. Truman had taken that step to mobilize resources for the Korean War and also to prevent a strike by steelworkers. The Court ruled, however, that the president lacked authority to seize private property.

In 2014, President Obama announced an executive order that would delay the deportation of millions of illegal immigrants. The order was met with strong opposition from Republicans. By the end of the year, 26 states, led by Texas, took legal action to stop Obama’s plan. The case made it to the Supreme Court, and a 4-4 split affirmed a lower court injunction, ultimately blocking Obama’s order. It was an eight-member Court due to the death of Justice Antonin Scalia.

Judicial Appointments

A more frequent encounter of the two branches comes when presidents appoint federal judges. All federal judges serve for life terms, so only a fraction of the federal courts will have openings during a president’s time in office. Yet presidents see this opportunity as a way to put like-minded men and women on federal benches across the country. Of course, like appointments in the executive branch, the Senate must approve these nominees.

While standoffs about Cabinet appointees are rare, judicial nominations are another story. Judges have greater influence of shaping the law and can serve for life, so there is more at stake. The president appoints scores of federal judges during each four-year term, because, in addition to the nine justices on the Supreme Court, nearly 1,000 federal judges serve the other federal courts.

Throughout U.S. history, 30 Supreme Court nominees have been rejected by a Senate vote. Many other lower court nominees have also been rejected or delayed to the point of giving up on the job.

The interaction between the branches on these judicial nominees is complicated and sometimes contentious. Senate rules and traditions govern the process. Senators, especially those on the Judiciary Committee, expect to advise presidents on selecting these nominees and are sometimes slow to consent to the president’s choices. They, too, realize the longevity of a federal judge’s service. If the president appoints like-minded judges, senators on the opposite end of the ideological spectrum are unlikely to welcome the judges, since their future decisions could define controversial or unclear law.

A divided electorate has caused majority control of the Senate to shift from one party to the other, and the cloture motion has served a somewhat stabilizing function. According to a 2013 decision, if a senator wants to block a judicial nomination with a filibuster, only a simple majority of senators would be required to prevent that.