Skip to: How a bill becomes a law

Congressional Structure

bicameral legislator

implied powers

implicit powers

necessary and proper clause

Congressional Behaviors

non-germane rider

pork-barrel spending

logrolling

Budget Bill

mandatory spending

discretionary spending

deficit spending

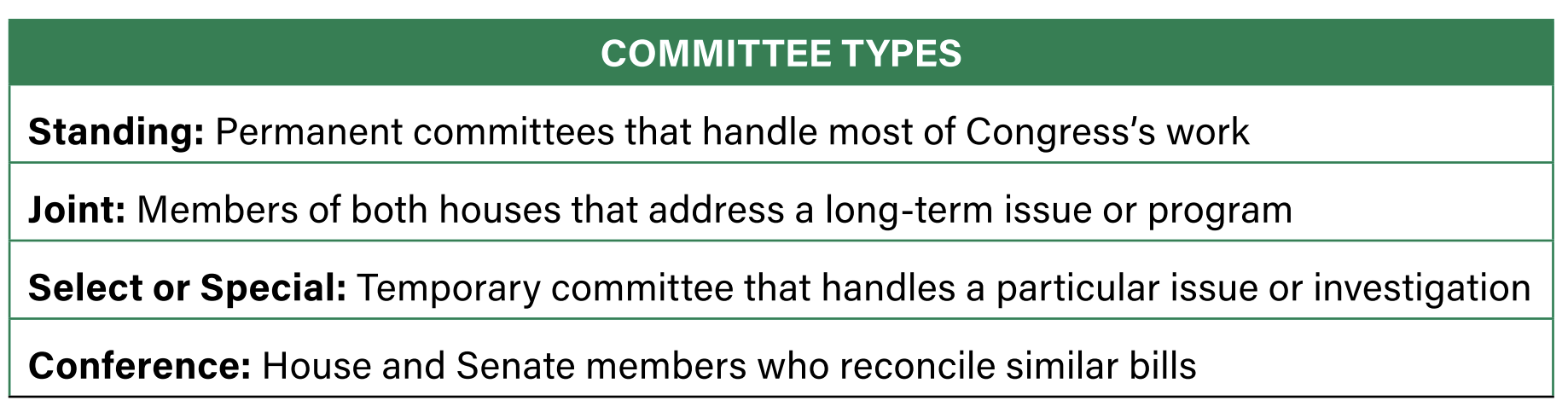

Committees

standing committee

joint committee

select committee

conference committee

House of Representatives

membership

Speaker of the House

Majority Leader, Minority Leader

Majority Whip, Minority Whip

Committee Chair

debate rules

The Senate

membership

President of the Senate

President Pro-tem

Majority Leader

Minority Leader

Majority/Minority Whip

debate rules

filibuster

cloture rule

Cases

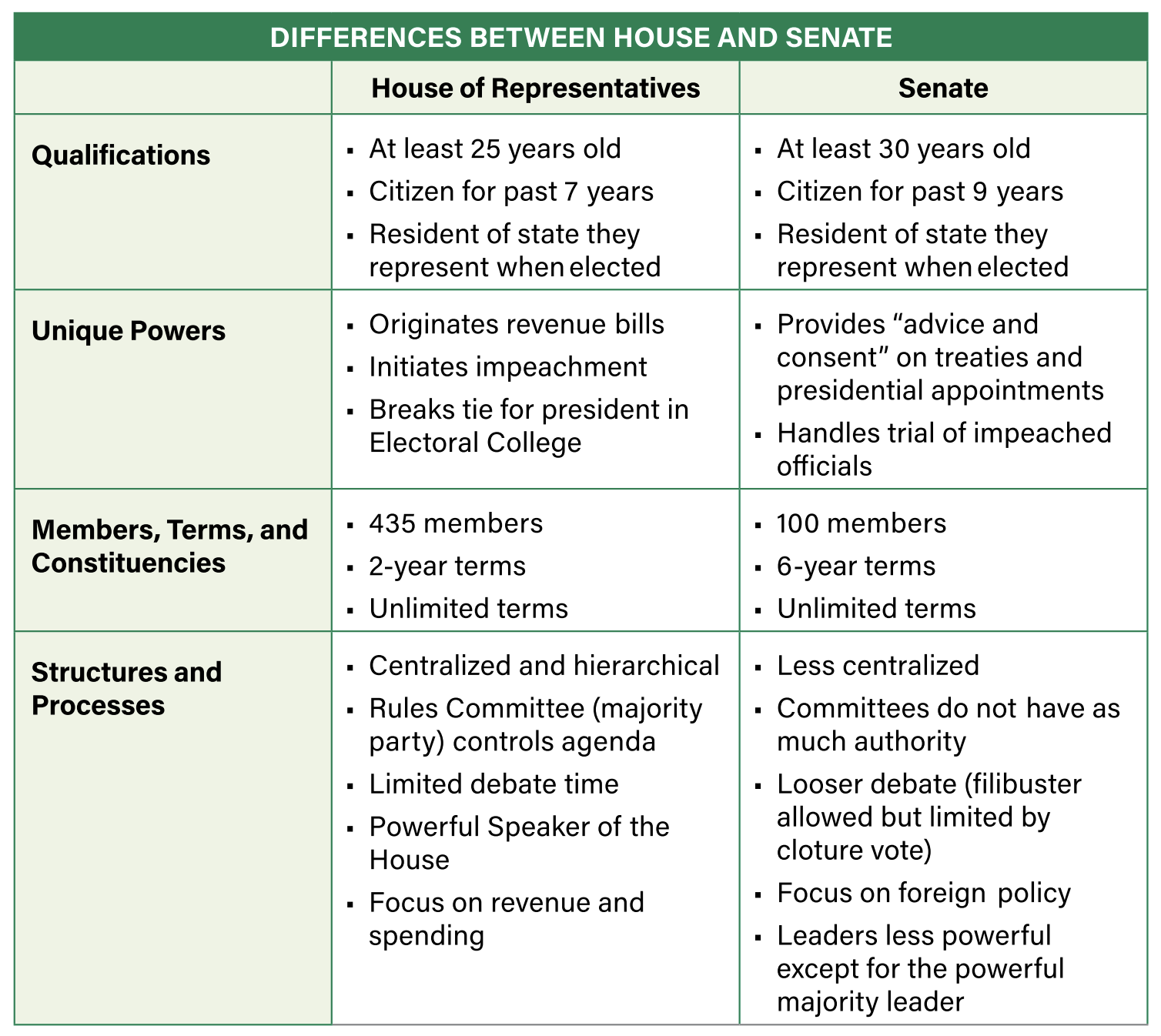

The United States Congress is one of the world’s most democratic governing bodies. Defined in Article I of the Constitution, Congress consists of the Senate and the House of Representatives. These governing bodies meet in Washington, DC, to craft legislation that sets out national policy. Congress creates statutes, or laws, that become part of the United States Code. Its 535 elected members and roughly 30,000 support staff operate under designated rules to carry out the legislative process. In January 2019, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi in the House of Representatives and Vice President Mike Pence in the Senate gaveled the 116th Congress to order for its new term.

Structure of Congress

After a war with Britain over adequate citizen representation and governance under the unworkable Articles of Confederation, creating a republican form of government that reflected citizen and elite views was of top concern for Americans at the Constitutional Convention. For that reason, the framers designed Congress as the most democratic and chief policymaking branch. The First United States Congress opened in 1789 in New York City.

Article I

The bicameral, or two-house, legislature resulted from a dispute at the Constitutional Convention between small and large states, each desiring different forms of representation. The Great Compromise (see Topic 1.5) dictated that the number of representatives in the House would be allotted based on the number of people living within each state. Article Is provision for a census every ten years assures states a proportional allotment of these members. Together, the members in the House represent the entire public. The Senate, in contrast, has two members from each state, granting states equal representation in that chamber. With this structure, the framers created a republic that represented both the citizenry at large and the states.

The framers also designed each house to have a different character and separate responsibilities. Senators are somewhat insulated from public opinion by their longer terms (six years as opposed to two for members of the House), and they have more constitutional responsibilities than House members. Because they represent an entire state, each has a more diverse constituency compared with the House. In contrast, smaller congressional districts give House members a more intimate constituent-representative relationship (there are seven small-population states that elect one at-large representative and two senators, which results in each member of Congress from those states representing the entire state).

Originally, unlike House members, senators were elected by state legislators. This practice, which is a form of elite democracy, changed with the Seventeenth Amendment, ratified in 1913. This amendment broadened democracy by giving the people of the state the right to elect their senators.

The requirement that both chambers must approve legislation helps prevent the passage of rash laws. James Madison pointed out that “a second house of the legislature, distinct from and dividing the power with the first, must always be a beneficial check on the government. It doubles the people’s security by requiring the concurrence of two distinct bodies.” This system of checks and balances in Congress helps keep an appropriate balance between majority rule and minority rights.

Size and Term Length

The more representative House of Representatives is designed to reflect the will of the people and to prevent the kinds of abuses that took place during the colonial period. Most representatives are responsible for a relatively small geographic area. With their two-year terms, House members must consider popular opinions, or unsatisfied voters will replace them. The entire House faces reelection at the same time.

Since 1913, the House has been composed of 435 members, with the temporary exception of adding two more for the annexation of Alaska and Hawaii. Each congressional district has more than 700,000 inhabitants. The Reapportionment Act of 1929 mandates the periodic reapportionment and redistribution of U.S. congressional seats according to changes in the census figures. Each decade, the U.S. Census Bureau tabulates state populations and then awards the proportional number of seats to each state. Every state receives at least one seat. States gain, lose, or maintain the same number of seats based on the census figures. Because almost all states gain population over a ten-year period, even some growing states will lose seats if they grow at a proportionately slower rate.

The Senate, in contrast, always has 100 members. George Washington explained the character of the U.S. Senate with an analogy to cooling hot coffee. “We pour our coffee into a saucer to cool it, we pour legislation into the senatorial saucer to cool it.” The framers wanted a cautious, experienced group to serve as yet another hurdle in the lawmaking process. Only one-third of the Senate is up for reelection every two years, making it a continuous body. In Federalist No. 64, John Jay argued, “by leaving a considerable residue of the old ones [senators] in place, uniformity and order, as well as a constant succession of official information, will be preserved.” Senators’ six-year terms give them some ability to temper the popular ideas adopted by the House, since senators do not have to worry about being voted out of office so soon. The reelection rate for Senators is nearly 90 percent.

Collectively, these two bodies pass legislation. Bills can originate in either chamber, except for tax proposals, or revenue laws, which must originate in the House. To become law, identical bills must pass both houses by a simple majority vote and then be signed by the president.

Caucuses

In addition to formal policymaking committees, Congress also contains groups of like-minded people organized into caucuses. These groups usually unite around a particular belief or concern. Each party has such a group in each house—the Democratic Caucus or the Republican Party Conference—which includes basically the entire party membership within each house. These groups gather to elect their respective leaders, to set legislative agendas, and to name their committee members. Many other smaller caucuses are organized around specific interests, some that cross party lines, such as agriculture, business, or women’s issues. Members can belong to multiple caucuses. Caucuses can have closed-door meetings and can develop legislation, but they are not officially part of the lawmaking process.

Since legislators are members of both caucuses and official congressional committees, they can formulate ideas and legislative strategy in the caucuses, but they must introduce bills through the official, public committee system.

With their longer terms, senators can build longer-lasting coalitions and working relationships. Although reelection rates tend to be high, House members with their shorter terms have more changeable coalition members.

Powers of Congress

The framers assigned Congress a limited number of specific powers, or enumerated powers. Expressly listed in Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, they are sometimes referred to as “expressed powers.” These powers allow for the creation of public policy—the laws that govern the United States.

Power of the Purse

The first congressional power enumerated is the power to raise revenue—to tax. Article I also provides that no money can be drawn from the treasury without the approval of Congress. Thus, Congress appropriates, or spends, those tax revenues through the public lawmaking process. Both chambers have committees for budgeting and appropriations. Congress also has the power to coin money.

The president proposes an annual budget while Congress members, who often differ on spending priorities, and their committees debate how much should be invested in certain areas. The budgeting process is complex and usually takes months to finalize.

Regulating Commerce

In recent years, Congress has used the commerce clause in Article I, Section 8, to assume authority over a wide policy area by connecting issues to every type of interstate and intrastate commerce. In an effort to protect the environment, for example, Congress has written regulations that apply to manufacturing and chemical plants to control the emissions these facilities might spew into our air. Congress can require gun manufacturers to package safety locks with the guns they sell. The commerce clause was the justification for the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), or “Obamacare,” which requires citizens to purchase health insurance and requires insurance companies to accept more clients.

However, there have been many legal challenges to wide-ranging congressional authority based on the commerce clause. The landmark case of United States v. Lopez (see Topic 1.8) is one of the few modern Supreme Court decisions that has restricted Congress’s use of this clause to expand the power of the federal government.

Foreign and Military Affairs

Congress is a key player in U.S. foreign policy, and it oversees the military. It can raise armies and navies, legislate or enact conscription procedures, mandate a military draft, and, most importantly, declare war. Congress determines how much money is spent on military bases and, through an independent commission, has authority over base closings. It essentially determines the salary for military personnel.

Foreign and military policy are determined jointly by Congress and the president, but the Constitution grants Congress the ultimate authority to declare war. The framers wanted a system that would send the United States to war only when deemed necessary by the most democratic branch, rather than by a potentially tyrannical or power-hungry executive making a solo decision to invade another country. Yet the framers also wanted a strong military leader who was responsible to the people, so they named the president the Commander in Chief of the armed forces. Congress does not have the power to deploy troops or receive ambassadors, leaving chief influences on foreign policy to the executive branch.

The commander-in-chief power was expanded after the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, which greatly enhanced a president’s authority in conducting military affairs. After nearly a decade of an unpopular and ultimately failed Vietnam War, Congress passed the War Powers Act in 1973. This law reigns in executive power by requiring the president to inform Congress within 48 hours of committing U.S. forces to combat. Also, the law requires Congress to vote within 60 days, with a possible 30-day extension, to approve any military force and its funding. The War Powers Act strikes a balance between the framers’ intended constitutional framework and the need for a strong executive to manage quick military action in the days of modern warfare.

Congress can choose to waive the 60-day requirement, as it did at the request of President George W. Bush after the September 11 attacks.

Implied Powers

At the end of the list of enumerated powers in Article I is the necessary and proper clause. It gives Congress the power “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers.” Also called the elastic clause, it implies that the national legislature can make additional laws intended to take care of the items in the enumerated list.

The elastic clause first came into contention in the case of McCulloch v. Maryland in 1819 over whether or not Congress could establish a bank. The Supreme Court ruled that items in the enumerated list implied that Congress could create a bank. Since then, the implied powers doctrine has given Congress authority to enact legislation addressing a wide range of issues economic, social, and environmental.

If those who served in the first Congress could take part in the modern legislature, “they would probably feel right at home,” says historian Raymond Smock. Other observers disagree and point to burgeoning federal government responsibilities. Using the elastic clause, Congress has expanded the size and role of the federal government. For example, it has created a Department of Education, defended marriage, and addressed various other modern issues outside the scope of Article I’s enumerated powers.

Differing Powers for House and Senate

Certain powers are divided between the House and the Senate. In addition to priority on revenue bills, the House also has the privilege to select the president if no candidate wins the majority in the Electoral College. The House can impeach a president or other federal officers in the event that a majority of the House agree that one has committed “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.”

The Senate, representing the interests of the states, also has several exclusive powers and responsibilities. Its advice and consent power allows senators to recommend or reject major presidential appointees such as Cabinet secretaries and federal judges. Senators often recommend people for positions in the executive branch or as U.S. district judges to serve in their states. High-level presidential appointments must first clear a Senate confirmation hearing, at which the appropriate committee interviews the nominee. If the committee approves the nominee, then the entire Senate will take a vote. A simple majority is required for appointment. Historically, the upper house, as the Senate is called, has approved most appointees quickly, with notable exceptions.

The Senate also has stronger powers related to foreign affairs. The Senate must approve by a two-thirds vote any treaty the president enters into with a foreign nation before it becomes official. While the House can level impeachment charges, only the Senate can try and if found guilty, remove the official from office with a two-thirds vote.

Despite their different powers, both chambers have equal say in whether or not a bill becomes law, since both chambers must approve an identical bill before it is passed on to the president for signing.

Structures, Powers, and Functions of Congress

Congress’s constitutional design shapes how it makes policy. Elected lawmakers work to improve the United States while representing people of unique views across the nation. The House and Senate differ overall, and within each are chamber-specific roles and rules that impact the law and policymaking process.

Congress is organized into leadership roles, committees, and procedures. Strong personalities and skilled politicians work their way into the leadership hierarchy, wielding great influence in running the nation’s government. The way in which ideas become law, or more often, fail to become law, is essential to understanding the structures, powers, and functions of Congress.

Policymaking Structures and Processes

The design of Congress and the powers the framers bestowed on the two chambers within that institution have shaped how the legislative branch makes policy. Elected lawmakers work to improve the United States while representing people of unique views across the nation. Formal groups and informal factions operate differently in the House and Senate. Congress is organized by house, political party, leadership, and committee. The parties create leadership positions to guide their own party members, to move legislation, and to carry out party goals. The party with the most members is the majority party and is in a strong position to set the agenda through its leaders and committee chairpersons. Standing committees are where the real work gets done, especially in the more structured House. Some of the powerful committees are institutions unto themselves, especially in the House. Congress’s formalized groups include both lawmaking committees and partisan or ideological groups.

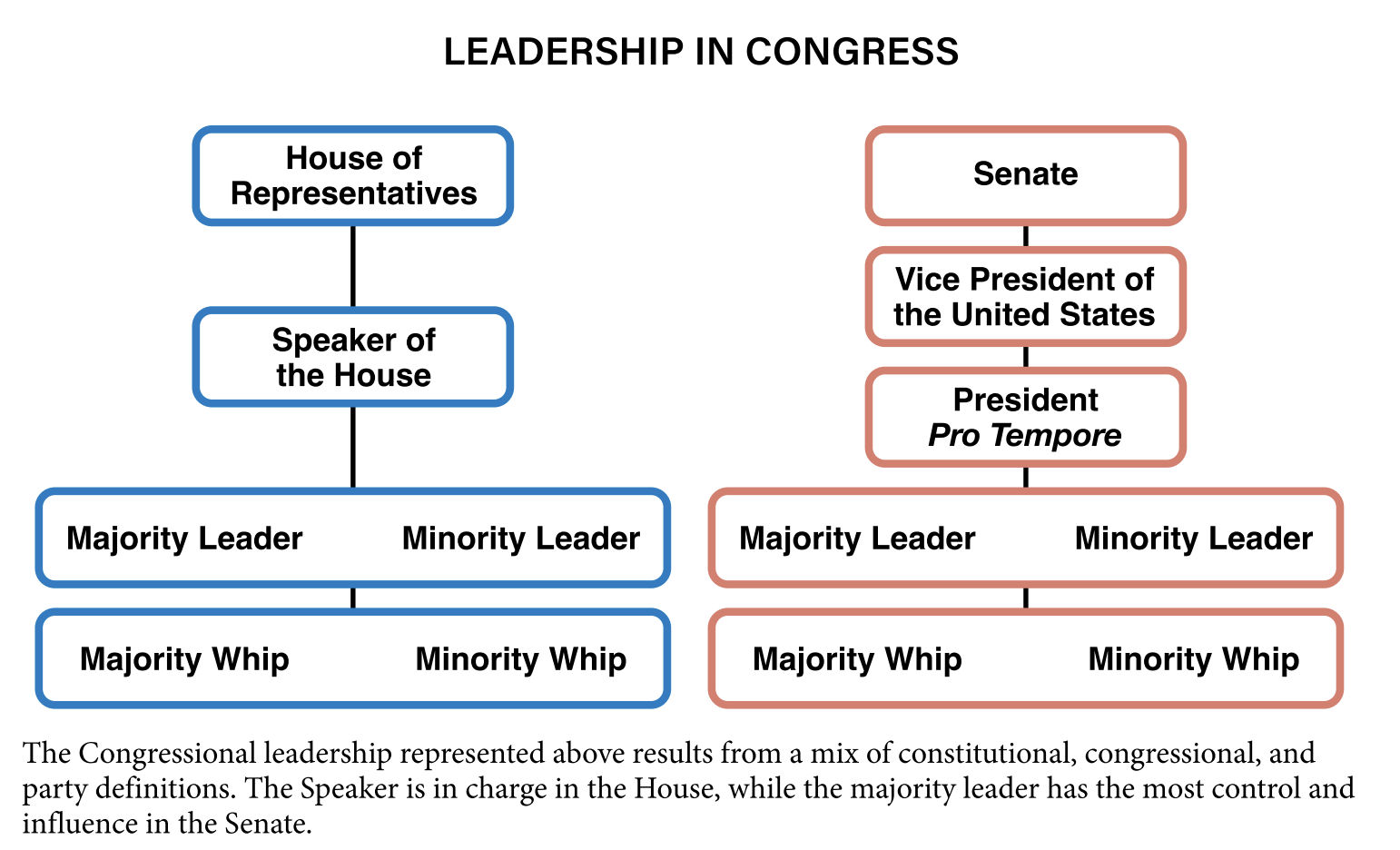

Leadership

The only official congressional leaders named in the Constitution are the Speaker of the House, the President of the Senate, and the president pro tempore of the Senate. The document states that the House and Senate “shall choose their other Officers.” At the start of each congressional term in early January on odd years, the first order of business in each house is to elect leaders. The four party caucuses—that is, the entire party membership within each house—gather privately after elections, but days before Congress opens, to determine their choices for Speaker and the other leadership positions. The actual public vote for leadership positions takes place when Congress opens and is invariably a party-line vote. Once the leaders are elected, they oversee the organization of Congress, help form committees, and proceed with the legislative agenda.

House Leaders

Atop the power pyramid in the House of Representatives is the Speaker of the House, which is the only House leadership position mentioned in the Constitution. As the de facto leader of the majority party in the House, the Speaker wields significant power. In 2007, Nancy Pelosi (D-CA) became the first female Speaker of the House and was reelected in 2019. Paul Ryan (R-WI) presided as Speaker over the Republican-controlled House before the Democrats regained the majority in the 2018 midterm elections.

The Speaker recognizes members for floor speeches and comments, organizes members for conference committees, and has great influence in most matters of lawmaking. On the next rung down in the House are the majority and minority leaders. These floor leaders direct debate from among their party’s members and guide the discussion from their side of the aisle. They are the first members recognized in debate. Party leaders have also become spokespersons for the party. They offer their party messages through news conferences and in interviews on cable networks and Sunday talk shows.

Below the floor leader is the deputy leader, or whip, who is in charge of party discipline. The whip keeps a rough tally of votes among his or her party members, which aids in determining the optimum time for a vote. Whips communicate leadership views to members and will strong-arm party members to vote with the party. Political favors or even party endorsements during a primary election can change the mind of representatives contemplating an independent or cross-party vote. The whip also assures that party members remain in good standing and act in an ethical and professional way. When scandals or missteps occur, the whip may insist a member step down from serving as a committee chair or leave Congress entirely.

Senate Leaders

In the Senate, a similar structure exists. The Constitution names the vice president as the nonvoting President of the Senate, but vice presidents in the modern era are rarely present. In lieu of the vice president as the presiding officer, senators in the majority party will share presiding duties. In case of a tie vote, the Constitution enables the vice president to break it.

Article I also provides for the president pro tempore, or temporary president. The “pro tem” is mostly a ceremonial position held by the most senior member of the majority party. The tasks involved with the role include presiding over the Senate in the absence of the vice president, signing legislation, and issuing the oath of office to new senators. The role of the president pro tem in presidential succession was addressed with the Twenty-fifth Amendment. Among several provisions, the Twenty-fifth Amendment states the president pro tem assumes the position of vice president if a vacancy in the office occurs.

The Senate majority leader wields much more power in the Senate than the vice president and pro tem. The majority leader is, in reality, the chief legislator, the first person the chair recognizes in debate and the leader who sets the legislative calendar and determines which bills reach the floor for debate and which ones do not. The majority leader also guides the party caucus on issues and party strategy. Senate leaders do not have final say in the decisions of individual party members; each makes his or her own independent choice, and the Senate’s less formal rules for debate enable members to address their colleagues and the public more easily than in the House. Former Senate majority leaders have expressed frustration over the effort to guide party members. Senator Bob Dole (R-KS, 1974-1996), who served in a number of leadership positions in the Senate, once said the letter “P” was missing from his title, “Majority Pleader.”

The Senate whips serve much the same purpose as their House counterparts, keeping track of party members’ voting intentions and attempting to maintain party discipline. Similarly, the conference chair in the Senate oversees party matters.

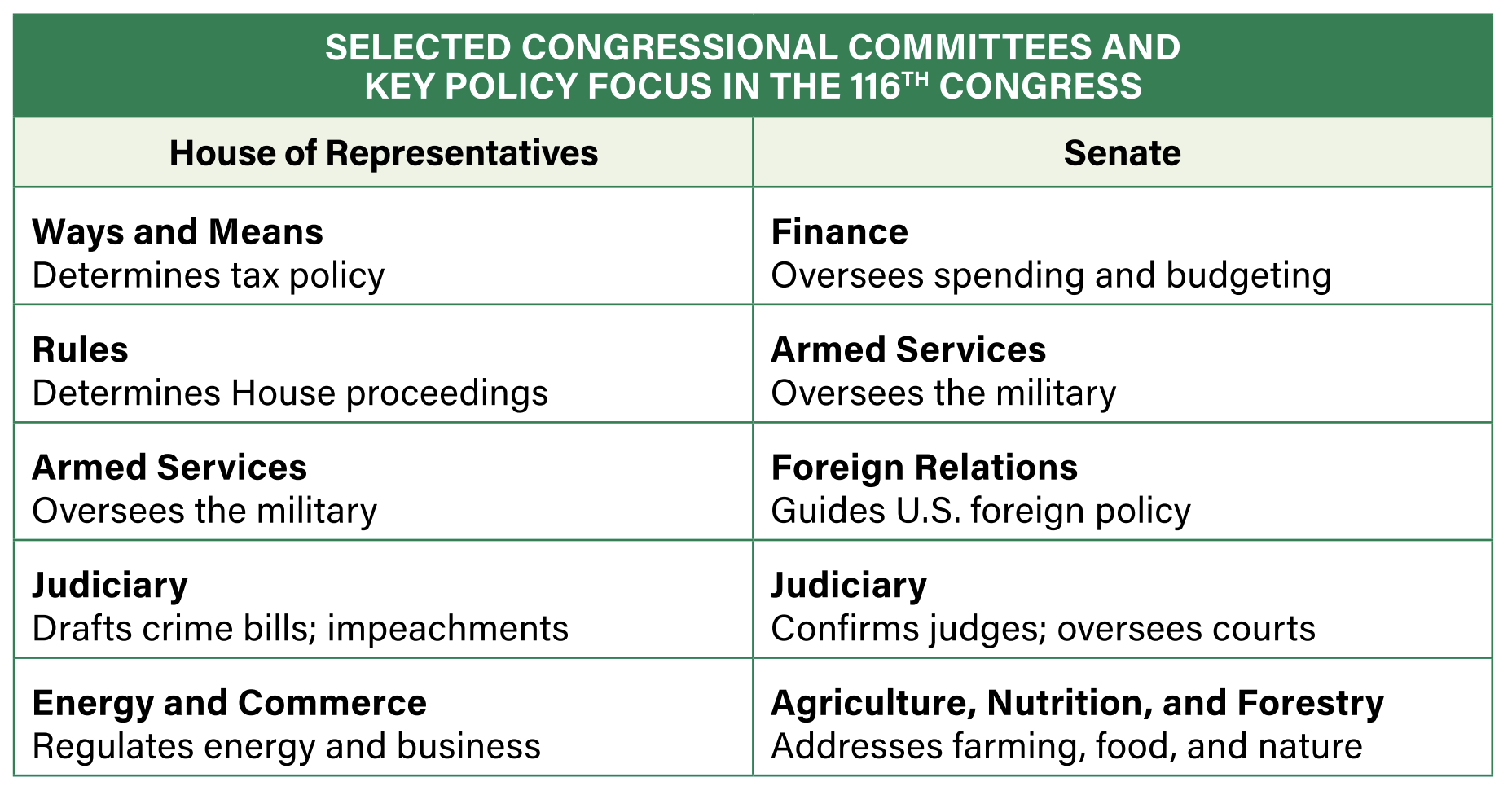

Committees, while not mentioned in the Constitution, play crucial roles in Congress. These smaller groups specialize in various policy areas, allowing lawmakers to focus on specific topics and draft detailed legislation. Standing committees, which are permanent and focused on specific policy areas like finance, foreign relations, and judiciary matters, conduct hearings, debate bills, and play essential roles in shaping legislation before it reaches the House or Senate floor.

In the Senate, as part of its advice and consent role, standing committees hold confirmation hearings for presidential nominations. For instance, nominees for positions such as secretary of defense must appear before committees like the Armed Services Committee for questioning before a recommendation is made to the full Senate.

Committee assignments are highly sought after by members of Congress, often based on expertise or the interests of their constituents. The process of assigning members to committees involves recommendations from party-specific committees like the Democrats’ Steering and Policy Committee and the Republicans’ Committee on Committees, followed by approval by the full House or Senate.

The Ways and Means Committee in the House, for example, holds significant power over tax policy, while the Appropriations Committees in both houses control government spending, making them influential in budgetary matters. These committees, along with others, ensure that legislative proposals are thoroughly examined and crafted before advancing through the legislative process.

Congress has a few permanent joint committees that unite members from the House and Senate, such as one to manage the Library of Congress and the Joint Committee on Taxation. Members of these committees do mostly routine management and research.

Both houses form temporary or select committees periodically for some particular and typically short-lived purpose. A select or special committee is established “for a limited time period to perform a particular study or investigation,” according to the U.S. Senate’s online glossary.

“These committees might be given or denied authority to report legislation to the Senate.” Select committees can be exclusive to one house or can also have joint committee status.

Notable select committees have investigated major scandals and events, such as the 2012 terrorist attack on the U.S. Consulate in Benghazi, Libya.

These groups also investigate issues to determine if further congressional action is necessary. Recently the House created a select committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming. A bill originally introduced in 1989, H.R. 40, was reintroduced in 2019 to establish a select committee to study the effects of slavery and possible reparations for descendants of the formerly enslaved.

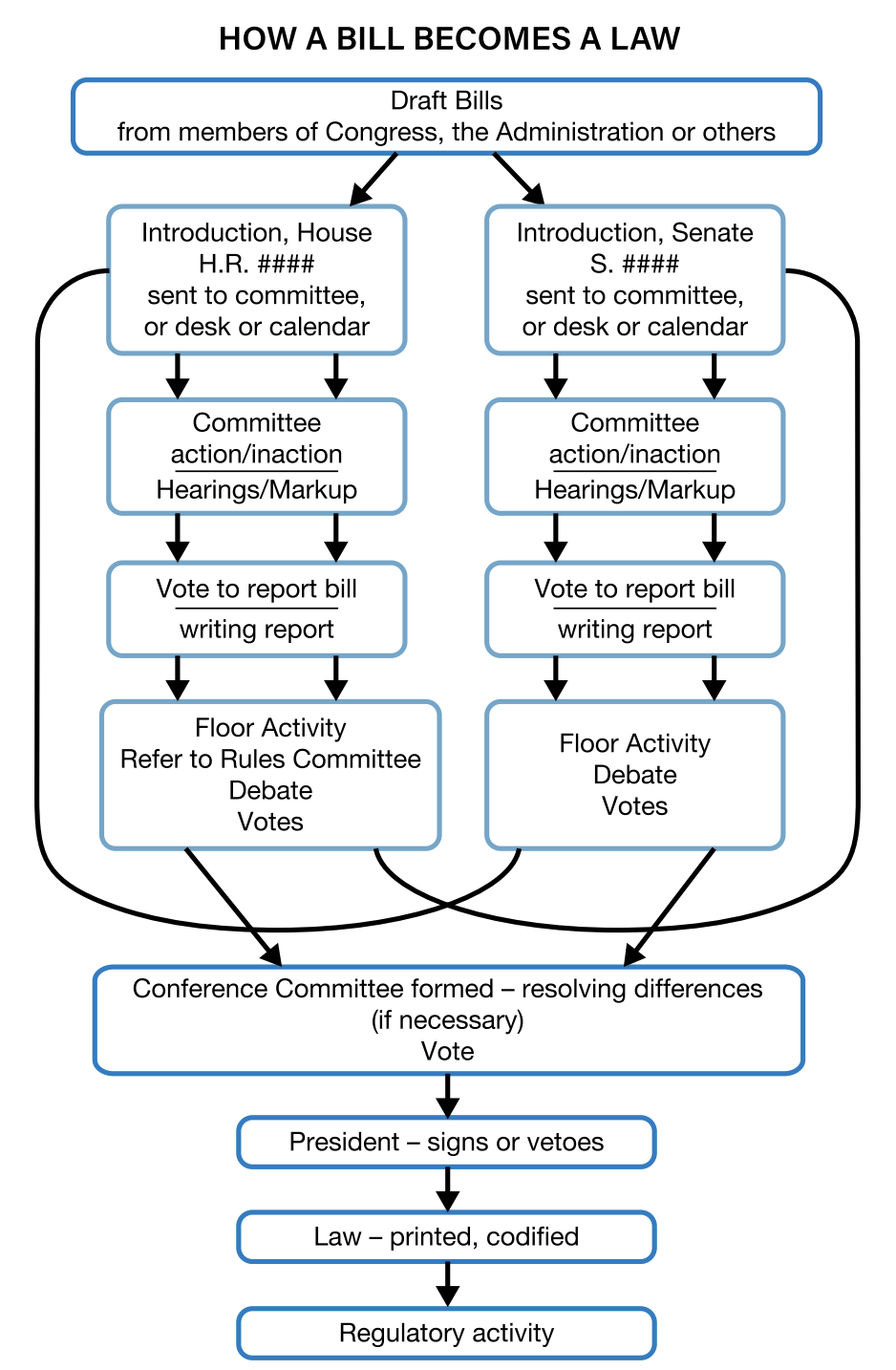

When a bill passes both houses but in slightly different forms, a temporary conference committee is created to iron out differences on the bill. It is rare that legislation on a particular issue will be identical when approved by both the House and Senate. When two similar bills pass each house, usually a compromise can be reached. Members from both houses gather in a conference committee for a markup session, a process by which the bill is edited or marked up. The final draft must pass both houses before going on to possibly receive the president’s signature.

In addition to creating bills and confirming presidential appointments, committees also oversee how the executive agencies administer the laws Congress creates. Through its committees, Congress conducts congressional oversight to ensure that executive branch agencies, such as the FBI or the TSA, are carrying out the policy or program as defined by Congress. When corruption or incompetence is suspected, committees call agency directors to testify. Oversight hearings also may simply be fact-finding exchanges between lawmakers and Cabinet secretaries or agency directors about congressional funding, efficiency, or just general updates.

Committees and Rules Unique to the House

Both the House and Senate follow parliamentary procedure outlined in Robert’s Rules of Order, guidelines for conducting discussion and reaching decisions in a group. With so many members representing so many legislative districts, however, the House has rules that limit debate. A member may not speak for more than an hour and typically speaks for less. These legislators can offer only germane amendments to a bill, those directly related to the legislation under consideration. In the House, amendments to bills typically must first be approved by the committee overseeing the bill.

The presiding officer—the Speaker of the House or someone he or she appoints—controls chamber debate. House members address all their remarks to “Madam Speaker” or “Mister Speaker” and refer to their colleagues by the state they represent, as in “my distinguished colleague from Iowa.” The control the presiding officer enjoys, time limits, and other structural practices help make the large House of Representatives function with some efficiency.

The House Rules Committee is very powerful. It can easily dispose of a bill or define the guidelines for debate because it acts as a traffic cop to the House floor. Nothing reaches the floor unless the Rules Committee allows it. This committee generally reflects the will and sentiment of House leadership and the majority caucus. It impacts every House bill because it assigns bills to the appropriate standing committees, schedules bills for debate, and decides when votes take place. The entire House must vote to make a law, but the Rules Committee wields great power in determining what issues or bills other members will vote on.

The Committee of the Whole is also unique to the House. It includes but does not require all representatives. However, the Committee of the Whole is more of a state of operation in which the House rules are relaxed than an actual committee. It was created to allow longer debate among fewer people and to allow members to vote as a group rather than in an individual roll call.

Additionally, the otherwise nonvoting delegates from U.S. territories—Puerto Rico, Guam, and others—can vote when the House operates in the Committee of the Whole. Only 100 members must be present for the Committee of the Whole to act. When it has finished examining or shaping a bill, the Committee “rises and reports” the bill to the House. At that point the more formal rules of procedure and voting resume, and, if a quorum is present, the entire House will vote on final passage of the bill.

A modern device that functions as a step toward transparency and democracy in the House is the discharge petition. The discharge petition can bring a bill out of a reluctant committee. The petition’s required number of signatures has changed over the years. It now stands at a simple majority to discharge a bill out of committee and onto the House floor. Thus, if 218 members sign, no chairperson or reluctant committee can prevent the majority’s desire to publicly discuss the bill. This measure may or may not lead to the bill’s passage, but it prevents a minority from stopping a majority on advancing the bill and is a way to circumvent leadership.

Rules and Procedures Unique to the Senate

The smaller Senate is much less centralized and hierarchical than the House with fewer restrictions on debate. Senators can speak longer. However, the presiding officer has little control over who speaks when, since he or she must recognize anyone who stands to speak, giving priority to the leaders of the parties. Like representatives, senators are not allowed to directly address anyone but the presiding officer. They refer to other senators in the third person (“the senior senator from Illinois, for example).

Senators can propose nongermane amendments. They can add amendments on any subject they want. Senators also have strategic ways to use their debate time. For example, they may try to stall or even kill a bill by speaking for an extremely long time, a tactic known as the filibuster, to block a nomination or to let the time run out on a deadline for voting on a bill.

Filibusters are a Senate procedure (not a constitutional power) that any senator may invoke and use to wear down the opposition or extract a deal from the Senate leadership. In contrast, the only House members who are allowed to speak as long as they want are the Speaker of the House, the majority leader, and the minority leader. On February 6, 2018, House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi spoke for eight hours straight in support of protections for people who were brought into the country illegally when they were children, the so-called “DREAMers.” She could not take a seat or a bathroom break for the entire time or else she would have had to yield the floor.

The Senate also uses measures that require higher thresholds for action than the House and that slow it down or speed it up. These include unanimous consent—the approval of all senators—and the hold, a measure to stall a bill.

Before the Senate takes action, the acting Senate president requests unanimous consent to suspend debate. If anyone objects, the motion is put on hold or at least stalled for discussion. For years, senators abused this privilege, since a few senators, even one, could stop popular legislation. Then and now, senators will place a hold on a motion or on a presidential appointment as a bargaining tool.

Such delays in the past have brought about changes in the rules. As the United States stepped closer to war in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson called for changes in Senate procedures so that a small minority of senators could not block U.S. action in arming merchant ships for military use. A filibuster had blocked his armed neutrality plan before the United States’ entrance into World War I. President Wilson was enraged. He said the Senate “is the only legislative body in the world which cannot act when its majority is ready for action. A little group of willful men have rendered the great government of the United States helpless.”

A special session created Rule 22, or the cloture rule, which enabled and required a two-thirds supermajority to stop debate on a bill, thus stopping a filibuster and allowing for a vote. In 1975, the Senate lowered the standard to three-fifths, or 60 of 100 senators. Once cloture is reached, each senator has the privilege of speaking for up to one hour on that bill or topic.

Foreign Policy Functions While both houses have a Foreign Affairs Committee, the Senate has more foreign relations duties. The framers gave the upper house the power to ratify or deny treaties with other countries. The Senate also confirms U.S. ambassadors. Because the Senate is smaller and originally served as agents of the states, the framers gave it more foreign policy power than the House. In Federalist No. 75, Hamilton pointed to its continuity.

“Because of the fluctuating and multitudinous composition of [the House, we can’t] expect in it those qualities … essential to the proper execution of such a trust.” The chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee works closely and often with the president and secretary of state to forge U.S. foreign policy.

The Legislative Process: How a Bill Becomes a Law

Lawmaking procedures in each house have been developed to guide policymaking and legislative customs. Both bodies have defined additional leaders that guide floor debate, assure party discipline, and serve as liaisons to the opposing party, the president, and the media. The framers declared in Article I that each house would determine its own rules as further assurance of a bicameral system.

Introducing and Amending Bills

Only House or Senate members can introduce a bill. Today, however, the actual authors of legislation are more often staffers with expertise, lobbyists, White House liaisons, or outside professionals. When a bill’s sponsor (the member who introduces it and typically assumes authorship) presents it, the bill is officially numbered. Numbering starts at S.1 in the Senate or H.R.1 in the House at the beginning of each biennial Congress.

Several events take place in the process, creating opportunities for a bill to drastically change along the way. Additional ideas and programs can become attached to the original bill. The nongermane amendments, or riders, are often added to benefit a member’s own agenda or programs or to enhance the political chances of the bill. Representative Morris (“Mo’) Udall (D-AZ) once expressed frustration when he had to vote against his own bill because it had evolved into legislation he opposed.

How each house, the president, and the public view a bill will determine its fate. The rough-and-tumble path for legislation often leads to its death. In a typical two-year period, thousands of bills are introduced and only a small portion are enacted into law. In the 115 Congress (January 2017-January 2019), representatives and senators introduced more than 13,000 bills and resolutions. About 9 percent, or 1,150, were enacted.

An omnibus bill includes multiple areas of law and/or addresses multiple programs. A long string of riders will earn it the nickname “Christmas Tree bill” because it often delivers gifts in the form of special projects a legislator can take home, and like the ornaments and tinsel on a Christmas tree, the “decorations” so many legislators added to the bill give it an entirely different look.

Pork-Barrel Spending One product of these legislative add-ons is pork barrel spending-funds earmarked for specific purposes in a legislator’s district. Federal dollars are spent all across the nation to fund construction projects, highway repair, new bridges, national museums and parks, university research grants, and other federal-to-state programs. Members of Congress try to “bring home the bacon,” so to speak. Riders are sometimes inserted onto bills literally in the dark of night by a powerful leader or chair, sometimes within days or hours before a final vote to avoid debate on them.

Constituents who benefit from pork barrel spending obviously appreciate it. Yet, in recent years the competition for federal dollars has tarnished Congress’s reputation. Citizens Against Government Waste reported an explosion of earmarks from 1994 to 2004. Congress passed more than five times as many earmarked projects, and such spending rose from $10 billion to $22.9 billion.

The most egregious example of pork barrel politics came when Senator Ted Stevens (R-AK) added a rider to a bill primarily meant to provide armor for U.S. troops in Iraq. The rider called for spending more than $400 million to connect a small community of about 50 residents and a regional airport to the Alaska mainland. Critics dubbed the construction project “The Bridge to Nowhere.”

Assigning Bills to Committee

The Senate majority leader and the House Rules Committee assign bills to committees in their respective chambers. Sometimes multiple committees have overlapping jurisdiction. A military spending bill may be examined by both the Armed Services Committee and the Appropriations Committee. In that case, the bill may be given multiple referral status, allowing both committees to address it simultaneously. Or it might have sequential referral status, giving one committee priority to review it before others. Frequently, subcommittees with a narrower scope are involved.

In committee, a bill goes through three stages: hearings, markup, and reporting out. If the committee “orders the bill,” then hearings, expert testimony, and thorough discussions follow. The chair will call for a published summary and analysis of the proposal with views from other participants, perhaps testimony from members of the executive branch or interest groups. Then the bill goes through markup, where committee members amend the bill until they are satisfied. Once the bill passes committee vote, it is “reported out” on the House or Senate floor for debate. The ratio of “yeas” to “nays” often speaks to the bill’s chances there. Further amendments are likely added. From this point, many factors can lead to passage and many more can lead to the bill’s failure.

The committee chair can also “pigeonhole” a bill—decide not to move it forward for debate until a later time, if at all.

Voting on Bills

Many lawmakers say one of their hardest jobs is voting. Determining exactly what most citizens want in their home state is nearly impossible. Legislators hold town hall meetings, examine public opinion polls, and read stacks of mail and emails to get an idea of their constituents’ desires. Members also consider a variety of other factors in deciding how to vote.

“Very often [lawmakers] are not voting for or against an issue for the reasons that seem apparent,” historian David McCullough once explained.

“They’re voting for some other reason. Because they have a grudge against someone… or because they’re doing a friend a favor, or because they’re willing to risk their political skin and vote their conscience.”

Logrolling Another factor affecting lawmaking is logrolling, or trading votes to gain support for a bill. By agreeing to back someone else’s bill, members can secure a vote in return for a bill of their own.

Generating a Budget One of the most important votes congressional members take is on the question of how to pay government costs. The budgeting process is a complicated, multistep, and often year-long process that begins with a budget proposal from the executive branch and includes both houses of Congress, a handful of agencies, and interest groups.

In the 1970s, Congress created the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and established the budgeting process with the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act (1974). ‘The OMB is the president’s budgeting arm. Headed by a director who is essentially the president’s accountant, the OMB considers the needs and wants of all the federal departments and agencies, the fiscal and economic philosophy of the president, federal revenues, and other factors to arrange the annual budget.

The 1974 act also defines the stages in reconciling the budget-passing changes to either revenue or spending by a simple majority in both houses with only limited time for debate-a process that can be used only once a year.

It calls for Congress to set overall levels of revenues and expenditures, the size of the budget surplus or deficit, and spending priorities. Each chamber also has an appropriations committee that allots the money to federal projects. The Senate Finance Committee is a particularly strong entity in federal spending.

Congress also created a congressional agency made of nonpartisan accountants called the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). This professional staff of experts examines and analyzes the budget proposal and serves as a check on the president’s OMB.

Sources of Revenue

For fiscal year 2019, the government expected to take in about $3.4 trillion. Every year, government revenue comes from five main sources:

- Individual income taxes-taxes paid by workers on the income they made during the calendar year. People pay different tax rates depending on their income level.

- Corporate taxes–taxes paid by businesses on the profits they made during the calendar year.

- Social insurance taxes (sometimes called payroll taxes)-taxes paid by both employees and employers to fund such programs as Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance.

- Tariffs and excise taxes -taxes paid on certain imports or products. The tariff on imports is meant to raise their price so U.S.-made goods will be more affordable and competitive. Excise taxes are levied on specific products-luxury products, for example, or products associated with health risks, such as cigarettes-as well as on certain activities, such as gambling.

- Other sources-taxes that include interest on government holdings or investments and estate taxes paid by people who inherit a large amount of money.

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending is payment required by law, or mandated, for certain programs. These programs include Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, unemployment insurance, and other special funds for people in temporary need of help. Congress has passed laws determining the eligibility for these programs and the level of payments, so on the basis of those laws mandatory spending happens automatically.

Of the $4.4 trillion, mandatory spending for 2019 was expected to be $2.7 trillion, more than 60 percent of the federal budget.

You may have noticed that the expected revenue for 2019 was $3.4 trillion, while the expected outlay was $4.4 trillion. The difference between spending and revenue, close to a trillion dollars in 2019, is the deficit. As in previous years, the government has to borrow money to pay that deficit, and each year’s loans add to the already large national debt of $20 trillion.

The interest payments on the national debt are massive and must be a part of the annual budget. In 2020, the interest will be more than $400 billion, or about 10 percent of the federal budget, and must also be paid out of each year’s revenue.

Some consider interest on debt as mandatory spending, since the government must pay its creditors or risk default, which would result in a serious financial crisis.

Discretionary Spending

Discretionary spending is funding that congressional committees debate and decide how to divide up. This spending about 38 percent of the 2019 budget-pays for everything else not required under mandatory spending. The chart below shows the percentage of government spending from 1950 to 2020 in various categories.