Need to Know:

conservative ideology

liberal ideology

Republican Party Platform

Democratic Party Platform

The modern Republican Party holds a conservative party doctrine. Republicans for decades have preached against wasteful spending and for a strong national defense, limited regulation of businesses, and maintaining cultural traditions.

Democrats, on the other hand, uphold a more liberal doctrine advocating for civil rights, women’s rights, and rights of the accused. Democrats also desire more government services to solve public problems and greater regulations to protect the environment.

These general ideological positions of the two major parties tend to determine the terms of debate on public policy issues. Additional minor parties are players in this political game and have a degree of influence in policymaking.

Political Ideologies

People take positions on public issues and develop a political viewpoint on how government should act in line with their ideology. An ideology is a comprehensive and mutually consistent set of ideas. When there are two or more sides to an issue, voters tend to fall into different camps, either a conservative or a liberal ideology. However, this diverse nation has a variety of ideologies that overlap one another.

Regardless of ideology, most Americans agree that the government should regulate dangerous industries, educate children at public expense, and protect free speech, at least to a degree. Everyone wants a strong economy and national security. These are valence issues – concerns or policies that are viewed in the same way by people with a variety of ideologies. When political candidates debate valence issues, “the dialogue can be like a debate between the nearly identical Tweedledee and Tweedledum,” says congressional elections expert Paul Herrnson.

In contrast to valence issues, wedge issues sharply divide the public. Wedge issues are used by political groups in strategic ways to gather support for an issue, especially among those who have yet to develop strong opinions. Wedge politics leaves little room for acceptance of competing ideas, each ideology considers their opinion right and the other side wrong. These could include the issues of abortion or the 2003 invasion and later occupation of Iraq.

The more divisive issues tend to hold a high saliency, or intense importance, to an individual or a group. For senior citizens, for example, questions about reform of the Social Security system hold high saliency. For people eighteen to twenty years old, the relative lack of job opportunities may have high saliency, since their unemployment rate is higher than that of older age groups.

The Liberal-Conservative Spectrum

Political scientists use the terms liberal and conservative, as well as the corresponding “left” and “right,” to label each end of an ideological spectrum.

Most Americans are moderate, meaning somewhere in between, and never fall fully into one camp or the other. Many others may think conservatively on some issues and have liberal beliefs on others.

Even labeling the two parties as liberal or conservative is an oversimplification. Some self-described conservatives want nothing to do with the Republican Party, and many Democrats dislike being labeled as liberal.

The meanings of the terms liberal and conservative have changed through history. In the early United States, a “liberal” government was one that did little. Thomas Jefferson believed in a high degree of liberty, declaring that a government that governs best is one that governs least. With this statement, Jefferson described the government’s liberal approach toward the people, allowing citizen freedom, a free flow of ideas, free markets, fewer laws, and fewer restrictions. This understanding of the word continued into the late nineteenth century.

In the Progressive Era (1890-1920), the federal government expanded its activity, going outside the confines of traditional government. Then, in the 1930s, Democratic President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) proposed a “liberal” plan for emergency legislation amidst the Great Depression. His New Deal agenda was new and revolutionary. The government took on new responsibilities in ways it never had. The government acted in a liberal way, less constrained by tradition or limitations that guided earlier governments.

Since the 1930s, the term liberal has usually meant being open to allowing the government to act flexibly and expand beyond established constraints.

The term conservative describes those who believe in following tradition and having reverence for authority. Modern-day conservatives often invoke Jefferson and argue that government should do less and thus allow people more freedom. In the early 1960s, Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater embraced the conservative label and published a book, The Conscience of a Conservative, en route to his 1964 Republican presidential nomination. He and much of his party believed that Roosevelt’s New Deal policies had unwisely altered the role of government. Goldwater and his party wanted less economic regulation and more responsibility on the citizenry. Many conservatives today call themselves “fiscal conservatives” because they want to see less taxation and less government spending overall.

Since FDR’s presidency and Goldwater’s nomination, these political terms have further evolved, and now it is difficult to know exactly what they mean. Roosevelt would likely not support some of the more liberal goals of the Democratic Party today, and Goldwater, in retirement, supported Democratic President Bill Clinton’s initiatives to open the military for LGBTQ volunteers and recruits. Additionally, an array of cultural and social issues that came to the forefront in the 1960s and 1970s changed the dynamic between those who consider themselves conservative and those who consider themselves liberal, thus changing the meaning of the terms.

Traditional Christian voters, family values groups, and others who oppose abortion and same-sex marriage and support prayer in school have adopted the conservative label and have aligned themselves with the Republican Party.

However, policies that restrict abortion, censor controversial material in books or magazines, or seek to more tightly define marriage actually require more, not less, law and regulation. For supporters of these policies, then, the conservative label is not necessarily accurate. People who believe in more regulation on industry, stronger gun control, and the value of diversity are generally seen as liberal. But when government acts to establish these goals, Jefferson might say, it is not necessarily acting liberally in relation to the rights of the people.

Off the Line

If you have trouble finding the precise line between liberal and conservative, you are not alone. Cleavages, or gaps, in public opinion make understanding where the public stands on issues even more difficult. Few people, even regular party members, agree with every conservative or every liberal idea. Many people simply do not fall on the linear continuum but rather align themselves with one of several other notable political philosophies: libertarian, populist, or progressive.

Voters who generally oppose government intervention or regulation are libertarian. As their name suggests, they have a high regard for civil liberties, those rights outlined in the Bill of Rights. They oppose censorship, want lower taxes, and dislike government-imposed morality. Though a small Libertarian Party operates today (in 2016, Libertarian candidate Gary Johnson won 3.2 percent of the national vote), more citizens claim the libertarian (small “l”) label than formally belong to the party. Libertarian-minded citizens can be found in both the Republican and Democratic parties. In short, libertarians are conservative on economic issues, such as government spending or raising the minimum wage, while they tend to be liberal on moral or social issues.

Most libertarians are pro-choice on abortion and support the equal treatment of LGBTQ people. As Nick Gillespie and Matt Welch of the libertarian Reason magazine write in their book, Declaration of Independents, “We believe that you should be able to think what you want, live where you want, trade for what you want, eat what you want, smoke what you want, and wed whom you want.”

Populists have a very different profile. Generally, a populist will attend a Protestant church and follow fundamental Christian ideas: love thy neighbor, contribute to charity, and follow a strict moral code. More populists can be found in the South and Midwest than along each coast. They tend to come from working-class families. They favor workplace safety protections and farm subsidies as necessary expenses for the welfare of the citizenry. Yet they also would curb obscene or unpatriotic speech and would be less sympathetic to the accused criminal defendant.

Donald Trump was the populists’ candidate in 2016. No serious observer would call Trump a populist, but there is little doubt populist voters helped swing the election in Trump’s favor. Men without a college degree who work in the Rustbelt factories of Youngstown, Detroit, and Pittsburgh, who normally vote Democratic, came out and voted for Trump. The blue-collar worker and those with steadfast religious views rallied around a strong voice and promises to protect police, veterans, and American jobs.

The Progressive Movement emerged in cities from the roots of the Republican Party. It peaked in the United States in the early 1900s when reformers challenged government corruption that ran counter to the values of equality, individualism, democracy, and advancement. At that time, the Republican Party split into its two wings: conservative and progressive.

Progressives criticized traditional political establishments that concentrated too much power in one place, such as government and business. Modern progressives are aligned with labor unions. They believe in workers’ rights over corporate rights, and they believe the wealthier classes should pay a much larger percentage of taxes than they currently do.

With some variation, 35 to 45 percent of Americans consider themselves moderate. Yet there are more conservatives than liberals in the U.S. In 1992, Gallup measured the difference between self-described conservatives at 36 percent and liberals at 17 percent, with 43 percent calling themselves moderate.

In 2019, the annual poll found self-described conservatives remained at 35 percent, but self-described liberals have risen steadily to 26 percent (35 percent claimed to be moderate). Views have changed, and so have the perceptions of these labels.

A 2020 Gallup survey on party affiliation found that 27 percent claimed to be Democrats, 30 percent called themselves Republicans, and 42 percent considered themselves independent. Many people’s views fall between these ideologies and between the two major political parties.

Party Platforms

The best way to determine a party’s primary ideology is to read its platform, or list of principles and plans it hopes to enact. Platforms are approved at the party’s national convention every four years, and committee members argue over the wording of the document. The arguments have revealed strong intraparty differences or fractures.

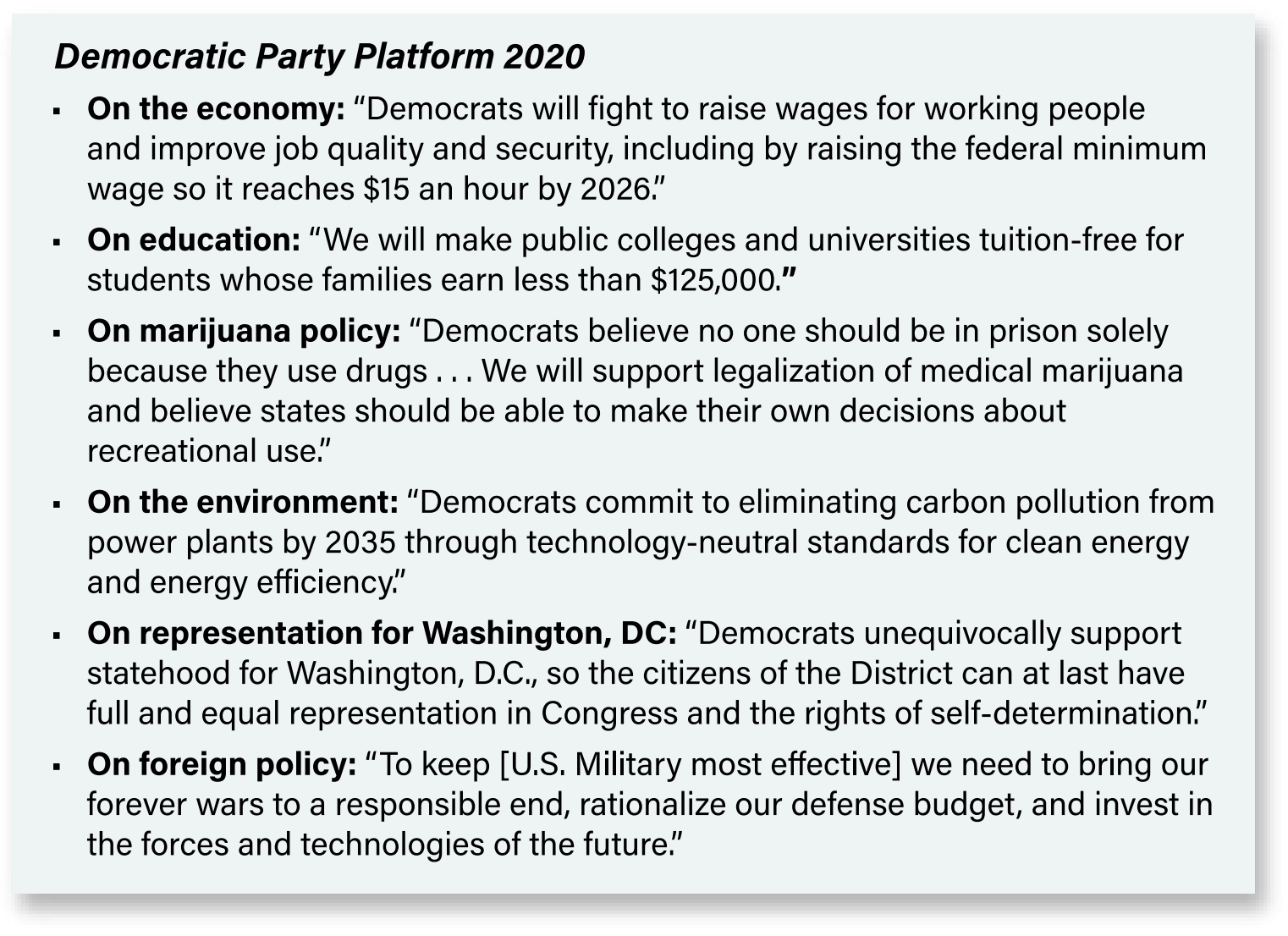

The Democratic party drafted and approved the first national party platform at its 1840 convention. It included nine major points and about 530 words. The 2020 Democrats’ platform is a 91-page document. The parties try to satisfy multiple groups within their tents and occasionally battle over particular wording that might go into the platform planks. Though the more liberal wing of the Democratic Party wanted language to eliminate fracking, legalize marijuana nationwide, abolish ICE (the federal government’s immigration agency); none of this made it into the platform. Democratic socialist and presidential contender Bernie Sanders ultimately supported the platform, but not all in his camp did. Below are some key quotes from the 2020 document.

These statements reveal why each party has a unique following of voters.

The Democrats have claimed that they are an inclusive party that works for minority rights. Republicans, on the other hand, rely on conservative voters who support limited gun regulation, anti-abortion legislation, and increased national security. The electoral map of recent years shows these same geographic trends. The Democratic Party generally carries the more liberal northeastern states and those on the West Coast, while Republicans carry most of the South and rural West and Midwest. In recent decades, Democrats have increased their votes among women, African Americans, and the fastest-growing minority in the United States, Hispanics.

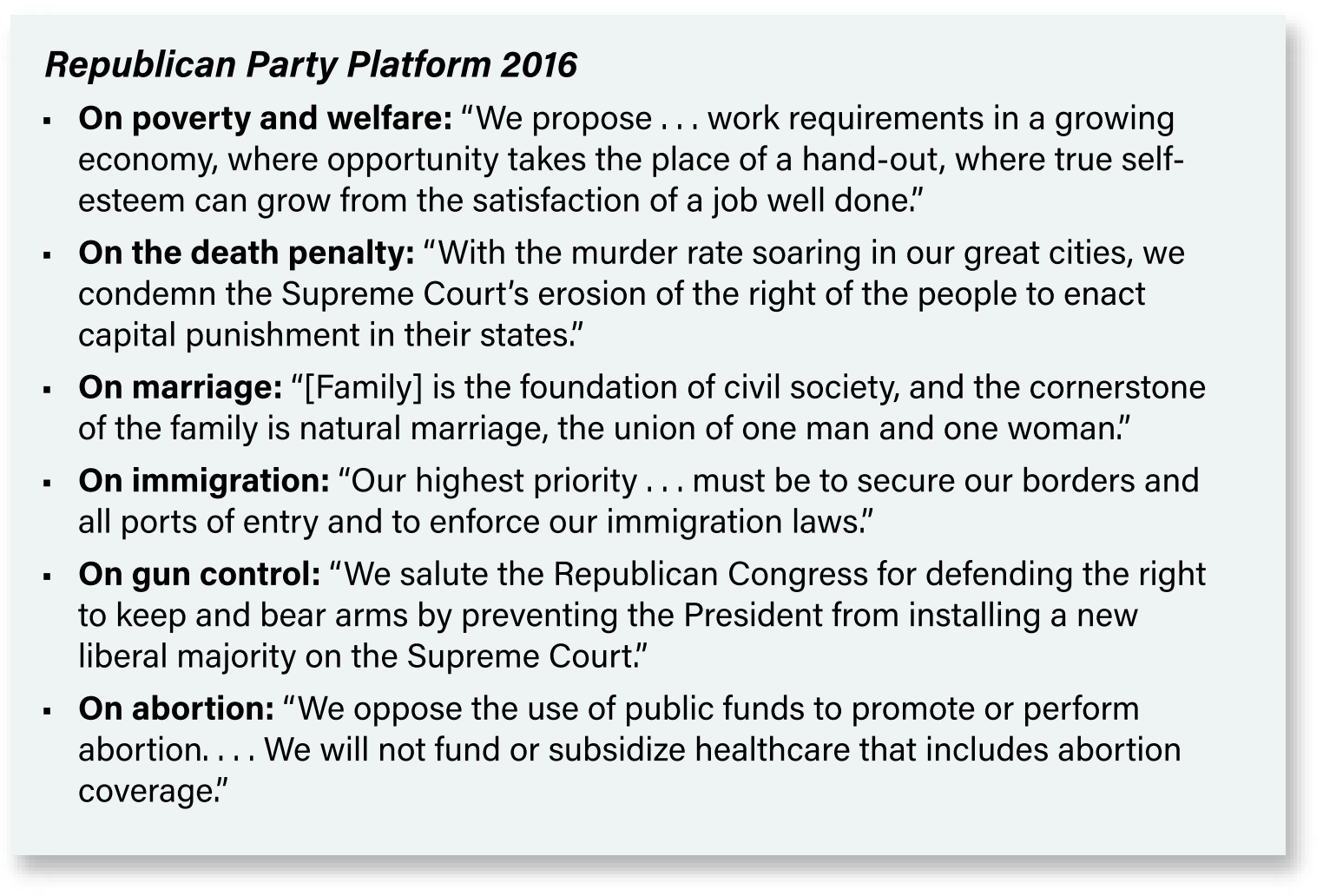

In 2020, for the first time in its history, the Republican Party did not issue an updated platform. Why this decision was made is unclear, leading some to draw different conclusions. One theory is that Donald Trump and those close to him wanted to simplify the document and take away the influence of longtime conservatives behind the scenes of the platform discussions. Amid the uncertainty of the COVID-19 summer of 2020 and tentative convention plans, the Republicans suggested that “logistics” prevented a platform update. To give a sense of Republican Party principles in contemporary times, parts of the 2016 platform are below.

Democrats and Republicans also tend to disagree on economic matters and issues related to law and order.

Democrats, for example, tend to support increasing government services for the poor, including health care, and they tend to support regulations on business to promote environmental quality and equal rights.

Republicans tend to oppose higher levels of government spending and the expansion of entitlements-programs such as Social Security and Medicare-while supporting a strong national defense. They also tend to support limited regulation of business.

On law and order, Democrats tend to prefer rehabilitation for prisoners over severe punishments and often oppose the death penalty.

Republicans tend to favor full prison sentences with few opportunities for parole and, as their platform states, they support the right of courts to impose the death penalty in certain cases.