Generational Effects:

Silent Generation

Baby Boomers

Generation X

Millennials

(Gen Z)

Lifecycle:

college-aged

marriage/early career/children

middle-aged

retirement-aged

senior

Political Events:

silent

boomers

gen x

millennials

(gen z)

Generation Z is in parantheses because it is not yet included in the College Board curriculum (probably because they’re all boomers who think high school kids are still millennials). Based on your knowledge of generational effects, effects of political events, and your own experience as a gen-z kid, create your own notes for these 2 sections. We’ll share thoughts in class.

At various points in the nations history the population may see similar events

very differently. Family, schools, peers, media, social environments, and location are key to an individual’s development of political attitudes. Other key factors include the generation in which a person was born and the person’s stage of life. For example, someone born in the 1930s who grew up during World War II is likely to have different views about America’s involvement in foreign wars than someone born in the 1950s who grew up during the Vietnam War. In a similar way, senior citizens wondering if they can afford to retire have different priorities from parents of young children who want better schools in their community.

Generational Effects

Many polls show the differing voting patterns for people in different generations.

In the past few presidential elections, Democrats have won a majority of the younger vote. The 2016 National Election Pool (NEP), a collaboration of the major TV news networks and Edison Research, found that Democrat Hillary Clinton won voters under 45 years old, and Republican President Trump won those 45 and older. Clinton’s share of younger voters was larger than Trumps share of older voters. Clinton won 56 percent of voters age 18 to 24, while Trump took only 34 percent of that age group. For those 65 years of age and over, Trump won 52 to 45 percent. The trend continued in 2020 as many younger voters moved to the Democrat’s camp. Biden won 65 percent of the 18-24 year-old bloc, while Trump took 52 percent of the over 65 crowd again.

Yet when we examine generations as voting blocs, we examine millions of people who come from all parts of the United States, each influenced not only by their age but also by additional demographic characteristics. In fact, there is more variation in political attitudes within a given generation or age bloc than between generations. As you have read, notable events can have different effects on liberal- or conservative-leaning citizens. Citizens in different generations can learn different lessons from the same events.

The impressionable-age hypothesis posits that people forge most of their political attitudes during the critical period between ages 14 and 24. Political and perhaps personal events occurring when a person is 18 are about three times as likely to influence partisan voting preferences as similar events occurring when a voter is 40 years old.

Political scientists, psychologists, and pollsters typically place Americans into four generational categories to measure attitudes and compare where they might stand on a political continuum. They include from youngest to oldest:

Millennials, Generation X, Baby Boomers, and the Silent Generation.

Different authorities define the cutoffs at slightly different years. The Silent Generation, those born before 1945, are senior citizens born during the Great Depression or as late as the aftermath of World War II. Baby Boomers (those born between 1946-1964) lived during an era of economic prosperity after World War II and through the turbulent 1960s. Generation X includes those Americans born after the Baby Boomers (between about 1962-1982), and Millennials came of voting age at or after the new millennium. Generation Z, those people born between 1995 and 2010, tend to share similar outlooks as Millennials but are still being defined. A look at two of the age groups on this timeline will show the role of generational effects on political socialization.

Millennials

This under-40 population tends to be more accepting of interracial and same-sex marriage, legalization of marijuana, and second chances in the criminal justice system than their elders. They are also more ethnically and racially diverse than previous generations. About 12 percent of Millennials are first-generation Americans. They tend to be tech-centered, generally supportive of government action to solve problems, and highly educated. They have a high level of social connectedness and great opportunities for news consumption.

By any measure, they are more liberal than previous generations. Gallup researcher Jeffrey Jones says that Millennials will remain more liberal and the United States will become more liberal as this group ages.

On Foreign Policy

As Millennials began reading their news online, they encountered a world characterized by a complex distribution of power, a network of state and non-state actors shaping the foreign policy process and international relations. Millennials’ frequent interactions with people not exactly like them and at great distances have led them to be more willing to promote cooperation over the use of force in foreign policy compared with other generations. Although they are hopeful about the future of the country, only about 70 percent of Millennials regard themselves as patriotic, a lower percentage than older Americans.

Economic Views

Millennials tend to follow a similar “stay out” mindset in regard to social questions and some economic questions, yet their lines separating government from the economy are not easy to draw. They are business friendly but not opposed to regulation. They want citizens to earn their way, but they want to protect the consumer, the environment, and society at large. Their coming of age in a post-Earth Day world has created a desire to protect the environment through recycling and other measures. They often acknowledge government waste and are troubled by it, but they believe in a higher degree of regulation than do typical conservatives. Nearly four out of five Millennials believe Americans should adopt a sustainable lifestyle by conserving energy and consuming fewer goods.

Millennials are more conservative on free trade and a meritocracy, with 48 percent saying that government programs for the poor undermine initiative and responsibility and 29 percent disagreeing with that statement.

Voting

Though Millennials’ views show subtle differences, their voting habits on Election Day do not. The Pew Research Center found in a 2016 study that 55 percent of 18- to 35-year-olds identified as Democrats or leaning Democrat, and 27 percent called themselves “liberal Democrats.” More than two out of three young Americans has a progressive tilt on energy, climate change, government efforts to assist people and the economy, and fighting inequality.

Silent Generation

On the opposite end of the age spectrum, senior citizens are defined as those over 65 years old. The Silent Generation and Baby Boomers overlap in this age group, but the following information focuses on the older generation. Unique times and political events shaped this generation’s thinking.

On Foreign Policy

Members of the Silent Generation are the last group to remember the era before the 1960s counterculture movement and before the Vietnam War. Most of this generation grew up hating communism, and many of them supported America’s nine-year involvement in Southeast Asia until the U.S. departure from the region in the mid-1970s. American prosperity, patriotism, and a Judeo-Christian moral code were foremost in shaping their views during their impressionable years.

On Social Issues

The same generation gave religious values high priority and opposed the cultural changes that came during the 1960s and 1970s. Racial integration led to more interracial marriage and societal acceptance of racial equality, but that acceptance came more slowly to those who grew up in segregated societies. The women’s movement changed the traditional roles of the family and eventually legalized abortion. Casual drug use and a counterculture movement caused many who had come of age in the 1950s and early 1960s to question the order of things, yet many of those who started voting in the 1970s stood with the old guard, influenced by their parents’ choices. They held conservative beliefs and questioned changing American values. As Molly Ball of The Atlantic explained in 2016, this cohort “has fought through the culture wars, has watched God and prayer leave the public square, and has watched immigration infiltrate U.S. society and culture.” The same group today wants government to be tougher on criminal defendants and terror suspects than do younger groups, they more often oppose gay marriage, and they are bewildered with states’ decisions to legalize marijuana. A 2016 PRRI-Brookings survey showed that a majority of those over 65 believe America’s “culture and way of life” have changed for the worse.

Voting

Seniors are the most reliable voters. The retired and elderly show up consistently to vote in the highest percentages. This group often has lifelong investment in their communities and concerns over many key issues, not just Social Security and Medicare, as is sometimes portrayed.

According to a 2015 study by the U.S. Census Bureau, in the 2014 midterm elections, 59 percent of those over 65 voted. National averages in most midterm elections average around 38 percent. In fact, this senior midterm measure beats most voting blocs even in presidential election years. The 55-64 year-old group turned out in large numbers in the 2016 presidential election, about 66 percent, but still somewhat lower than their elders whose turnout was about 71 percent.

Lifecycle Effects

Just as each generation experiences dynamic social changes, people experience change as they move through the life cycle. Lifecycle effects include the variety of physical, social, and psychological changes that people go through as they age. These can affect political socialization in several ways. For one, they can shift focus to issues that are important at different age levels. For example, many college-age students are concerned about the accumulation of student debt and the challenges in finding a job that provides both a good income and health insurance benefits. In part because of these concerns, many Millennials and the following generation were drawn to the candidacy of U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) in the Democratic presidential primaries in 2016 and 2020 because he called for free education at public colleges, more corporate regulations, and an expansion of Medicare—the health insurance program for seniors managed by the government—to include everyone, paid for in part by a tax increase for the wealthiest citizens.

When people in this group move into the next stage of life, which often involves marriage and family, their priorities might shift to other issues related to a stable economy and to schools their children might attend. At this point, a second lifecycle effect also becomes apparent. The demands of adult responsibility and raising children may limit the amount of active political participation people in this stage of the lifecycle can manage. They may be less able to volunteer in election efforts or to participate in demonstrations.

Just as young adults focus on the issues that matter at their life stage, seniors are worried about things that matter most as they age. The American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), the powerful interest group that directly represents more than 40 million seniors, lists among its major issues on its website: Social Security, health issues, Medicare, retirement, and consumer protection. Retirees who have paid into the Social Security system start collecting their benefits, and trips to the doctor become necessary and more expensive. According to a 2016 AARP study, 81 percent of seniors think prescription drug prices are too expensive and 87 percent say they support a tax credit to help families afford caregivers.

By the time they become seniors, people have had a full life to forge their political attitudes and to practice political habits—consuming news, interacting with government on a local level, and developing the habit of voting. They have likely already registered to vote and are familiar with voting routines, and they usually don’t have to schedule voting around work.

Influence of Political Events on Ideology

Political beliefs can be shaped by major national political events, such as war, a charismatic president completing his agenda, or a landmark Supreme Court ruling that alters society. Events closer to home can also have lasting political impact. Watching a friend or loved one benefit or be harmed by affirmative action, serving in a war zone, or experiencing the effects of very high taxes or business regulation costs can shape one’s views of national policy.

Influence of Major Political Events

Each generation has its own political and economic events that bring about dynamic social change. Living through these events has an influence on political attitudes and socialization.

The Older Generation

Those who endured the economic hardships of the Great Depression (1929-1933) lived in an era in which many people had a favorable attitude toward government involvement in social life. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal put people back to work by creating government jobs related to infrastructure (roads, canals, railroads) and even the arts. Social Security provided support for seniors and lifted many members of that age group out of poverty. Through the political socialization process, these events influenced ideology—in this case advancing trust in the government and support for the role of government in providing a social safety net.

As the Depression waned, the United States became involved in World War II. The war brought the nation together against fascism, creating a sense of united purpose and a belief in the reliability of the government. Women’s entrance into the workforce to help industrial output of needed war materials redefined the role of women in society and helped shape political attitudes about gender.

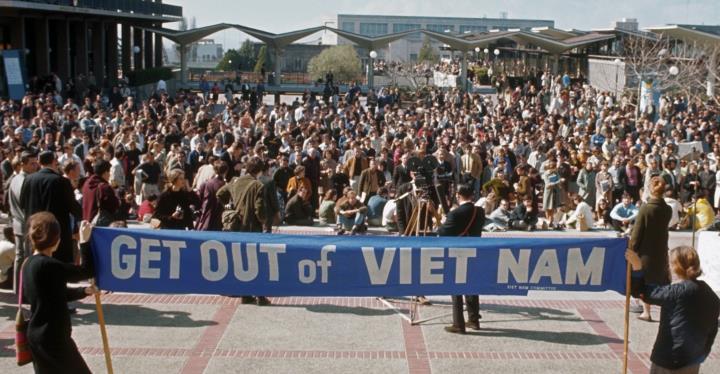

After World War II, the Russians (Soviets at the time) replaced the Axis powers as the new enemy, and the United States stood up to totalitarianism and the Soviet annexation of or influence on vulnerable nations. The Vietnam War was one of the final major efforts that placed large numbers of American GIs on the battlefield to defeat communism. As the mission in Vietnam proved to be a failure and as a rising number of Americans disagreed with U.S. involvement, many of those over 35 years old, especially blue-collar workers and those in rural communities, differed from the Baby Boomers. Unlike the Boomers, these Americans trusted and supported their government on the way into Vietnam and refrained from criticizing their government as failure became imminent. They were more forgiving of their government in the aftermath of the conflict.

The Baby Boomers

“Where were you when you heard that President Kennedy had been shot?” is a question most people of school age or older in 1963 can answer without a second thought. Such an event has a lasting impact on a person’s absorption of political culture. Kennedy’s assassination was one of an unfortunate number of assassinations during the 1960s: presidential candidate and brother Robert Kennedy and civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. These assassinations were in the same decade known for protests—of racial segregation and discrimination, of the United States’ involvement in the conflict in Vietnam, and the draft of young men to defend the interests of the country in Vietnam. Mass protests were a feature of the political culture of the time and influenced the political socialization of both participants and observers as an active democracy engaged members of society over life and death matters. Challenging the government became a political norm, and people tended to feel they had the power to bring about social changes through their actions.

From 1992 to 2006, Boomers were primarily a Democratic voting group. They took the place of the Silent Generation—the massive New Deal Coalition of Americans who voted for Franklin Roosevelt and Democrats who followed him—after the elders died. However, as Boomers aged, they joined other seniors in flocking to the Republican Party from the Democratic Party, a consistent trend that began in 2006 and held true on election night in 2016.

The shift of this generation is due in part to the shift in policy positions by each of the major parties. The Democratic Party, though redefined as “liberal” economically in the New Deal era, still held somewhat conservative views and dominated in the South into the 1970s and 1980s. As the party took on more liberal social views, supporting the right to abortion, same-sex marriage, and affirmative action, followers of Roosevelt and their children have shifted to the Republican Party.

The Younger Generation

The two seminal events in Millennials’ formative years were the September 11, 2001 attacks orchestrated by al-Qaeda (see Topic 1.5) and the military conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq that followed. Two schools of thought prevail on how Millennials view the September 11 attacks. One is that the attack on U.S. soil calls for aggressive homeland security and counterterrorism measures. Events that threaten national security have led Millennials to patriotism and trust in government, although in smaller percentages than older groups. Another point of view is that the event should serve as a wake-up call that the United States should be less involved in the Middle East. Some studies report that 53 percent of Millennials believe the United States ultimately provoked the attacks.

The U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) military attacks on Afghanistan following September 11 and the 2003 Iraq invasion and subsequent occupation have also helped shape Millennials’ views. The war in Afghanistan eventually surpassed Vietnam as America’s longest military conflict, and the chief premise for invading Iraq, a search for weapons of mass destruction, proved groundless. This younger generation will likely compare future conflicts to the war in Iraq, predisposing this cohort to be more reluctant to intervene or use military force than older generations. A 2014 study by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs found that almost 50 percent of Millennials say the United States should stay out of world affairs, the largest percentage by a generational group since the Council began the survey in 1974.

Many in this generation became politically aware around the time of the Great Recession (2007-2012). Studies show that growing up in an economic recession can greatly shape attitudes toward government redistribution of wealth—welfare and Social Security. Nearly 70 percent of Millennials accept the idea of government intervention in a failing economy, 10 percent more than the next older cohort. Pessimistic views formed during a sudden economic downturn tend to be long-lasting. Such experiences could increase the chances these citizens vote for a Democratic presidential candidate by 15 percent.

In the 2016 presidential election, Millennials favored the Democratic Party by 43 percent, while only 26 percent of that group favored the Republican Party. About 10 percent of Millennials voted for someone other than Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton, while those 40 and older voted for minor candidates only about 4 percent of the time.