Need to Know:

civil rights vs civil liberties

African American Civil Rights Movement

Letter from a Birmingham Jail

Women’s rights movement

NOW

ERA

Title IX (9)

Civil Rights Act

Voting Rights Act

LGBTQ+ rights movement

The United States places a high priority on freedom and equality and civil rights, protections from discrimination based on such characteristics as race, color, national origin, religion, and sex. These principles are evident in the founding documents, later constitutional amendments, and laws such as the 1964 Civil Rights Act. They are guaranteed to all citizens under the due process and equal protection clauses in the Constitution and according to acts of Congress. Civil rights organizations representing African Americans and women have pushed for government to deliver on the promises in these documents. In recent years, other groups-Latinos, people with disabilities, and LGBTQ individuals-have petitioned the government for fundamental fairness and equality. A pro-life movement emerged to fight for the rights of the unborn, and a pro-choice movement fought for the right of women to control decisions about their bodies. All three branches have responded in varying degrees to these movements and have addressed civil rights issues. Even so, racism, sexism, and other forms of bigotry have not disappeared. Today, a complex body of law shaped by constitutional provisions, Supreme Court decisions, federal statutes, executive directives, and citizen-state interactions defines civil rights in America.

Equality in Black and White

In the United States, federal and state governments generally ignored civil rights policy before the Civil War. ‘The framers of the Constitution left the legal question of slavery up to the states, allowing the South to strengthen its plantation system and relegate enslaved and free African Americans to subservience. The North had a sparse black population and little regard for fairness toward African Americans. Abolitionists, religious leaders, and progressives sought to outlaw slavery and advocated for African Americans in the mid-1800s.

The NAACP Pushes Ahead

The Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause spurred citizens to take action. One organization, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP stood apart from the others in promoting equal rights for African Americans. State-sponsored discrimination and a violent race riot in Springfield, Illinois, led civil rights leaders to create the NAACP in 1909. On Abraham Lincoln’s birthday, a handful of academics, philanthropists, and journalists sent out a call for a national conference. Harvard graduate and Atlanta University professor Dr. W.E.B. DuBois was among those elected as the association’s first leaders. By 1919, the organization had more than 90,000 members.

Before World War I, the NAACP and its leaders pressed President Woodrow Wilson to overturn segregation in federal agencies and departments. ‘The citizen group had also hired two men as full-time lobbyists in Washington, one for the House and one for the Senate. The association joined in filing a case to challenge a law that limited voter rights based on the then-legal status of voters’ grandparents. (See Topic 3.11 for more on this “grandfather clause.”) The Supreme Court ruled the practice a violation of the Fifteenth Amendment. Two years later, the Court again sided with the NAACP when it ruled government-imposed residential segregation a constitutional violation.

Legal Defense Fund

The NAACP has regularly argued cases in the Supreme Court. It added a legal team that was led by Charles Hamilton Houston, a Howard University law professor, and his assistant, Baltimore native Thurgood Marshall. They defended mostly innocent black citizens across the South in front of racist judges and juries. They successfully convinced the Supreme Court to outlaw the white primary-a primary in which only white citizens could vote. In southern states, the white primary had essentially extinguished the post-Civil War Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, allowing southern Democrats to stay in power and pass discriminatory laws.

The NAACP began a legal strategy to chip away at state school segregation, filing lawsuits to integrate first college and graduate schools and then K-12 schools. Early success came in 1938, when Lloyd Gaines integrated the University of Missouri’s Law School. The state had offered to pay his out-of-state tuition at a neighboring law school, but the Fourteenth Amendment specifically requires states to treat the races equally and failing to provide a “separate but equal” law school, the Court claimed, violated the Constitution.

In 1950, the NAACP won decisions against schools in Oklahoma and Texas to provide integrated graduate and law schools.

Additional groups joined the NAACP in the effort to make the United States a place of equality. The Congress on Racial Equality, the Urban League, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., took up the cause of racial equality. The civil rights movement had a pivotal year in 1963, with both glorious and horrific consequences. On one hand, King assisted the grassroots protests in Birmingham and more than 200,000 people gathered in the nation’s capital for the March on Washington. On the other hand, Mississippi NAACP leader Medgar Evers was shot and killed. In Birmingham, brutal police Chief Bull Connor turned fire hoses and police dogs on peaceful African American protesters.

Amid the face-offs and protests of the movement, in one of the darker but telling moments of the movement, authorities arrested Dr. Martin Luther King for leading a protest despite a court order forbidding civil rights demonstrations.

From his cell in the Birmingham jail, he wrote his discourse on race relations at the time.

Women’s Rights Movement

Obtaining the franchise, the right to vote, was key to altering public policy toward women, and Susan B. Anthony led the way. In 1872, in direct violation of New York law, she walked into a polling place and cast a vote. An all-male jury later convicted her. She later authored the passage that would eventually make it into the Constitution as the Nineteenth Amendment (1920).

Women and Industry

Industrialization of the late 1800s brought more women into the workplace. They often worked for less pay than men in urban factories. In 1908, noted attorney Louis Brandeis defended an Oregon law preventing women from working long hours. Brandeis argued that women were less suited physically for longer hours and needed to be healthy to bear children. The Court upheld a state’s right to make laws that treated women differently. This consideration protected the health and safety of women, but the double standard gave lawmakers justification to treat women differently.

Suffragists pressed on. By 1914, 11 states allowed women to vote. In the 1916 election, both major political parties endorsed the concept of women’s suffrage in their platforms and Jeanette Rankin of Montana became the first woman elected to Congress. The following year, however, World War I completely consumed Congress and the nation and the issue of women’s suffrage drifted into the background.

After the war ended, suffragist leader Alice Paul continued to press President Woodrow Wilson, eventually persuading him to support women’s suffrage. President Wilson pardoned a group of arrested suffragists and spoke in favor of the amendment, influencing Congress’s vote. The measure passed both houses in 1919 and was ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.

From Suffrage to Action

What impact did the amendment have on voter turnout for women? An in-depth study of a Chicago election from the early 1920s found that 65 percent of potential women voters stayed home, many responding that it wasn’t a woman’s place to engage in politics or that the act would offend their husbands.

Initially, men outvoted women by roughly 30 percent, but that statistic has changed and now turnout at the polls is higher for women than men.

Voting laws were not the states’ only unfair practice. The Supreme Court had ruled in 1948 that states could prevent women from tending bar unless the establishment was owned by a close male relative and states were allowed to seat all-male juries. However, women made advancements in the workplace in the 1960s. In 1963, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act that required employers to pay men and women the same wage for the same job. However, even after the Equal Pay Act, it was still legal to deny women job opportunities. That is, equal pay applied only when women were hired to do the same jobs that men were hired to do. The 1964 Civil Rights Act protected women from discrimination in employment.

In addition, Betty Friedan, the author of The Feminine Mystique, encouraged women to speak their minds, to apply for male-dominated jobs, and to organize for equality in the public sphere. Friedan went on to cofound the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966.

Women and Equality

In the 1970s, Congress passed legislation to give equal opportunities to women in schools and on college campuses. Pro-equality groups pressured the Court to apply the strict scrutiny standard—the analysis by courts to guarantee legislation is narrowly tailored to avoid violation of laws—to policies that treated genders differently. The application of strict scrutiny can be seen most clearly in Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which guaranteed that women have the same educational opportunities as men in programs receiving federal government funding.

However, the women’s movement fell short of some of its goals. The Court never declared that legal gender classification deserves the same level of strict scrutiny as classifications based on race. Additionally, the movement was unable to amend the Constitution to declare absolute equality of the sexes.

The proposed Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) stated “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied on account of sex” and gave Congress power to enforce this. The amendment passed both houses of Congress with the necessary two-thirds vote in 1972. Thirty of the thirty-eight states necessary to ratify the amendment approved the ERA within one year. At its peak, 35 states had ratified the proposal, but when the chance for full ratification expired in 1982, the ERA failed. Nonetheless, the 1970s was a successful decade for women gaining legal rights and elevating their political and legal status.

LGBTQ Rights and Equality

Like African Americans and women, those who identify as LGBTQ have been discriminated against and have sought and earned legal equality and rights to intimacy, military service, and marriage.

State and federal governments had long set policies that limited the freedoms and liberties of LGBTQ people. President Eisenhower signed an executive order banning any type of “sexual perversion,” as it was defined in the order, in any sector of the federal government. Congress enacted an oath of allegiance for immigrants to assure that they were neither communist nor gay.

State and local authorities closed gay bars. Meanwhile, the military intensified its exclusion of homosexuals.

The first known public gay rights protest outside the White House took place in 1965. In 1973, psychiatrists removed homosexuality as a mental disorder from their chief diagnostic manual. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, in part to seek legal protections and gain a political voice, homosexuals “came out” and began publicly proclaiming their sexual identity. A quest for legal marriage followed.

Debates regarding these issues are complex, with a wide array of overlapping constitutional principles. The states’ police powers, privacy, and equal protection are all involved. Federalism and geographic mobility create additional complexities. To what degree should the federal government intervene in governing marriage, a reserved power of the states? When gays and lesbians moved from one state to another, differing state laws concerning marriage, adoption, and inheritance brought legal standoffs as the Constitution’s full-faith-and-credit clause (Article IV) and the states’ reserved powers principle (Tenth Amendment) clashed.

Seeking Legal Intimacy

Traditionalists responded to the growing visibility of gays by passing laws that criminalized homosexual behavior. Though so-called anti-sodomy laws had been around for more than a century, in the 1970s, states passed laws that specifically criminalized same-sex relations and behaviors. In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), the Court struck down a state law that declared “a person commits an offense if he engages in deviate sexual intercourse with another individual of the same sex.” Lawrence’s attorneys argued that the equal protection clause voided this law because the statute specifically singled out gays and lesbians.

The Court agreed.

Military

Up to the late 20th century, the U.S. military discharged or excluded homosexuals from service. In the 1992 presidential campaign, Democratic candidate Bill Clinton promised to end the ban on gays in the military. Clinton won the election but soon discovered that neither commanders nor the rank and file welcomed reversing the ban. In a controversy that mired the first few months of his presidency, Clinton compromised as Congress passed the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy in 1994. This rule prevented the military from asking about the private sexual status of its personnel but also prevented gays and lesbians from acknowledging or revealing it. In short, “don’t ask, don’t tell” was meant to cause both sides to ignore the issue and focus on defending the country.

The debate continued for 17 years. Surveys conducted among military personnel and leadership began to show a favorable response to allowing gays to serve openly. In December 2010, with President Obama’s support, the House and Senate voted to remove the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy so all service members could openly serve their country.

Marriage

Not long after Hawaii’s state supreme court became the first statewide governing institution to legalize same-sex marriage in 1993, lawmakers elsewhere reacted to prevent such a policy change in their backyards. Utah was the first state to pass a law prohibiting the recognition of same-sex marriage. In a presidential election year at a time when public opinion was still decidedly against gay marriages, national lawmakers jumped to define and defend marriage in the halls of Congress. The 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) defined marriage at the national level and declared that states did not have to accept same-sex marriages recognized in other states. The law also barred federal recognition of same-sex marriage for purposes of Social Security, federal income tax filings, and federal employee benefits. This was a Republican-sponsored bill that earned nearly every Republican vote.

Democrats, however, were divided on it. Civil rights pioneer and Congressman John Lewis declared, “I have known racism. I have known bigotry. This bill stinks of the same fear, hatred, and intolerance.” The sole Republican vote against the law came from openly gay member Steve Gunderson who asked on the House floor, “Why shouldn’t my partner of 13 years be entitled to the same health insurance and survivor’s benefits that individuals around here, my colleagues with second and third wives, are able to give them?” The bill passed in the House 342 to 67 and in the Senate 85 to 14. By 2000, 30 states had enacted laws refusing to recognize same-sex marriages in their states or those coming from elsewhere.

If members of the LGBTQ community could legally marry, not only could they publicly enjoy the personal expressions and relationships that go with marriage, they could also begin to enjoy the practical and tangible benefits granted to heterosexual couples: financing a home together, inheriting a deceased partner’s estate, and qualifying for spousal employee benefits. In order for these benefits to accrue, states would have to change their marriage statutes.

Initial Legalization

The first notable litigation occurred in 1971 when Minnesota’s highest court heard a challenge to the state’s refusal to issue a marriage license to a same-sex couple. The Supreme Court upheld the decision to not recognize the marriage largely based on the definition of marriage in the state’s laws and in a dictionary.

These may seem like simple sources for courts to consult, but the issue is very basic: Should the state legally recognize same-sex partnerships and, if so, should the state refer to it as “marriage”? In the past two decades, the United States has battled over these two questions, as advocates sought legal equality and as public opinion on these questions shifted dramatically.

Vermont was an early state to legally recognize same-sex relationships and did so via the Vermont Supreme Court. The legislature then passed Vermont’s “civil unions” law, which declared that same-sex couples have “all the same benefits, protections and responsibilities under law . .. as are granted to spouses in a civil marriage” but stopped short of calling the new legal union a “marriage.” Massachusetts’ high court also declared its traditional marriage statute out of line, which encouraged the state to legalize same-sex marriage there. What followed was a decade-long battle between conservative opposition and LGBTQ advocates, first in the courts and then at the ballot box, creating a patchwork of marriage law across the United States. By 2011, more than half of the public consistently favored legalizing same-sex marriage, and support for it has generally grown since.

Two Supreme Court rulings secured same-sex marriage nationally. The first was filed by New York state resident Edith Windsor, legally married in Canada to a woman named Thea Spyer. Spyer died in 2009. Under New York state law, Windsor’s same-sex marriage was recognized, but it was not recognized under federal law, which governed federal inheritance taxes. Windsor thus owed taxes in excess of $350,000. A widow from a traditional marriage in the same situation would have saved that amount. The Court saw the injustice and ruled that DOMA created “a disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma” on same-sex marriage that was legally recognized by New York.

After separate rulings in similar cases at the sixth and ninth circuit courts of appeals, the Supreme Court decided to hear Obergefell v. Hodges (2015). In that case, the Court considered two questions: Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to issue a marriage license to two people of the same sex?” and “Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to recognize a marriage between two people of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out-of-state?” If the answer to the first question is “yes,” then the second question becomes moot. On June 26, 2015, the Court ruled 5:4 that states preventing same-sex marriage violated the Constitution.

Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote the opinion, his fourth pro-gay rights opinion in nearly 20 years.

Issues Since Obergefell

Within a year of the same-sex marriage ruling, the percent of cohabiting married same-sex couples rose from about 38 to 49, according to Congressional Quarterly. Now the Court has ruled that states cannot deny gays the right to marry, but not all Americans have accepted the ruling. Some public officials refused to carry out their duties to issue marriage licenses, claiming that doing so violated their personal or religious views of marriage. In 2016, about 200 state-level anti-LGBT bills were introduced (only four became law). Though the Obergefell decision was recent and was determined by a close vote of the Court, public opinion is moving in such a direction that the ruling is on its way to becoming settled law. Yet controversies around other public policies-such as hiring or firing people because they are transgender, refusing to rent housing to same-sex couples, or refusing business services, such as catering, for same-sex weddings-affect the LGBT community and have brought debates and changes in the law.

Workplace Discrimination

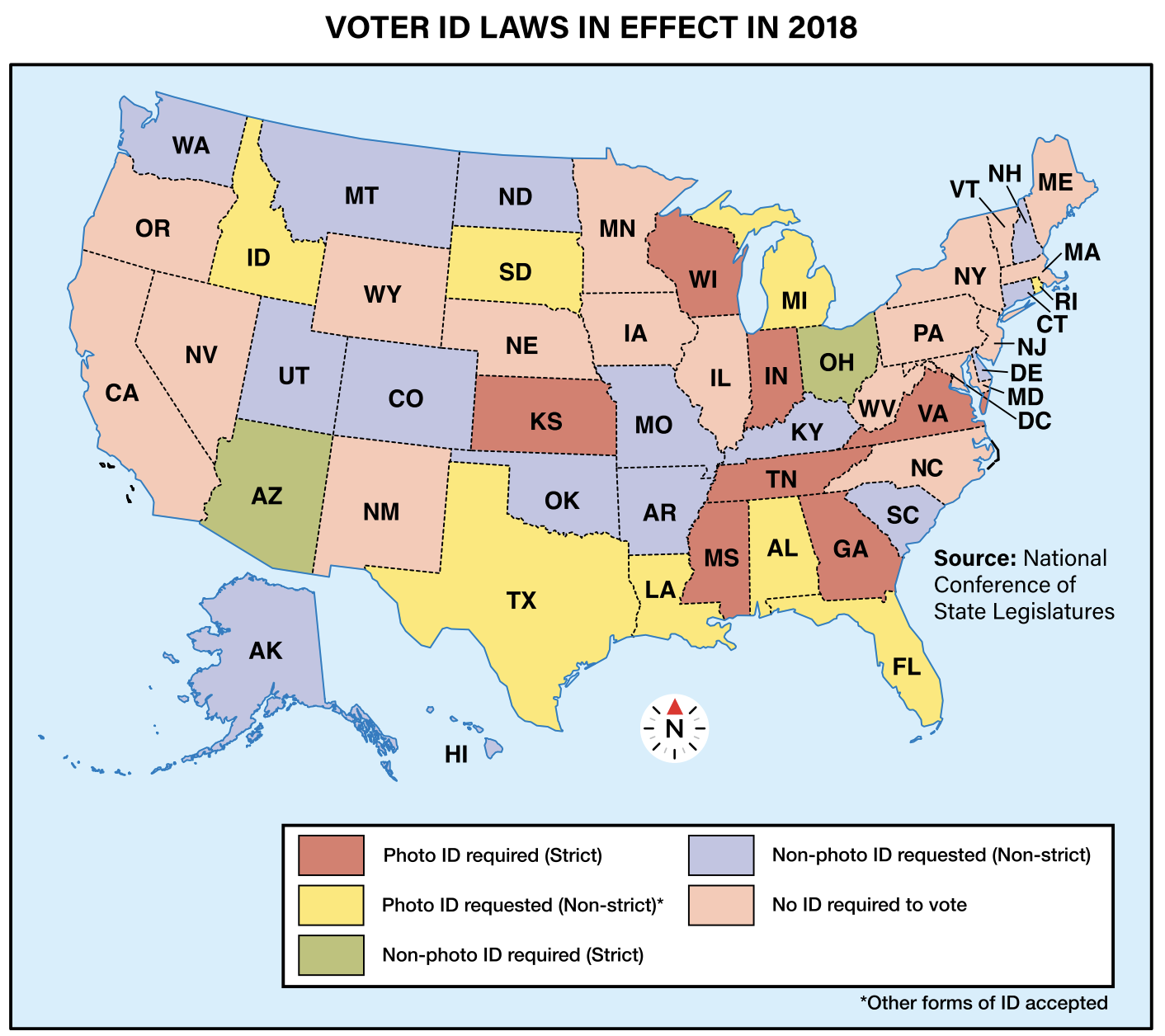

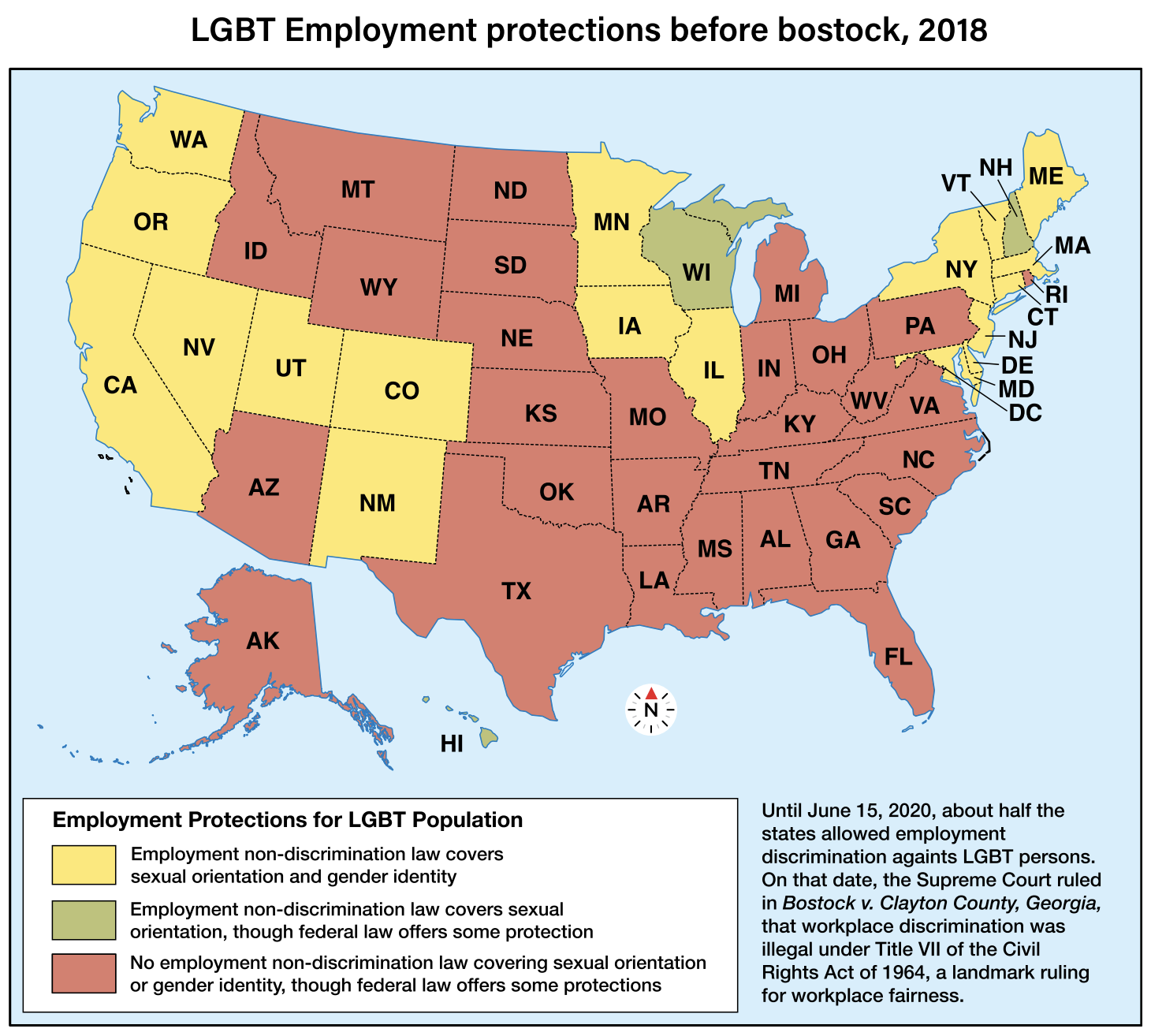

When the 1964 Civil Rights Act prevented employers from refusing employment or firing employees for reasons of race, color, sex, nationality, or religion, it did not include homosexuality or gender identity as reasons. No federal statute has come to pass that would protect LGBT groups. Twenty-two states and the District of Columbia barred such discriminatory practices and afforded a method for victims of such discrimination to take action against the employer. Conservatives argued that these policies created a special class for the LGBT community and were thus unequal and unconstitutional. (The map on the next page shows the states’ employment protections in 2018.) However, a 2020 landmark Supreme Court decision in Bostock v. Clayton County held that workplace discrimination was illegal throughout the nation under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

Sexual harassment is another expression of workplace discrimination. In the 1986 case Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson, the Supreme Court ruled that sexual harassment creates unlawful discrimination against women by fostering a hostile work environment and is a violation of Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Sexual harassment became a major issue in 2017 when a number of women came forward to accuse men in prominent positions in government, entertainment, and the media of sexual harassment. In a number of the high-profile cases, the accused men lost their jobs and the victims received financial compensation. In a show of solidarity and to demonstrate how widespread the problem of sexual harassment is, the #MeToo movement went viral. Anyone who had experienced sexual harassment or assault was asked to write #MeToo on a social media platform. Millions of women took part. A 2016 report by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found that between 25 and 85 percent of women experience sexual harassment at work but most are afraid to report it for fear of losing their jobs.

Refusal to Serve and Religious Freedom

The 1964 Civil Rights Act did not include LGBT persons when it defined the persons to whom merchants could not refuse service, the so-called public accommodations section of the law. So, depending on the state, businesses might have the legal right to refuse products and services to same-sex couples planning a wedding. In reaction to Obergefell, a movement sprang up to enshrine in state constitutions wording that would protect merchants or employees for this refusal, particularly if it is based on the merchant’s religious views. How can the First Amendment promise freedom of religion if the state can mandate participation in some event or ceremony that violates the individual’s religious beliefs? About 45 of these bills were introduced in 22 states in the first half of 2017. Debate and litigation continue in an effort to resolve the clash between religious liberty and equal protection.

Transgender Issues

How schools and other government institutions handle where transgender citizens go to the restroom or what locker room they use is another area of conflict. Several “bathroom bills” have surfaced at statehouses across the country. The issue has also been addressed at school board meetings and in federal courts. President Obama’s Department of Education issued a directive based on an interpretation of language from Title IX to guarantee transgender students the right to use whatever bathroom matched their gender identity. President Donald Trump’s administration rescinded that interpretation. The reversal won’t change policy everywhere, but it returns to the states and localities the prerogative to shape policy on student bathroom use, at least for now as courts are also examining and ruling on the issue.

By the mid-20th century, the Supreme Court had started to deliver decisions in favor of civil rights groups and their goal of integration. The NAACP (see Topic 3.10) had already filed several suits in U.S. district courts to overturn Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had provided the justification for K-12 segregation. The group filed suits across the South and found a greater number of willing plaintiffs and fewer white reprisals in the border South. With assistance from sociologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, two academics from New York, the NAACP improved its strategy. In addition to arguing that segregation was morally wrong, they argued that separate schools were psychologically damaging to black children. In experiments run by the Clarks, when black children were shown two dolls identical except for their skin color and asked to choose the “nice doll,” they chose the white doll. When asked to choose the doll that “looks bad,” they chose the dark-skinned doll. With these results, the Clarks argued that the segregation system caused feelings of inferiority in the black child. Armed with this scientific data, attorneys sought strong, reliable plaintiffs who could withstand the racist intimidation and reprisals that followed the filing of a lawsuit.

Legislating Toward Equality

As the events of the early 1960s unfolded, President John F. Kennedy (JFK) became a strong ally for civil rights leaders. His brother Robert Kennedy, the nation’s attorney general, dealt closely with violent, ugly confrontations between southern civil rights leaders and brutal state authorities. Robert persuaded President Kennedy to act on civil rights. President Kennedy began hosting black leaders at the White House and embraced victims of the violence.

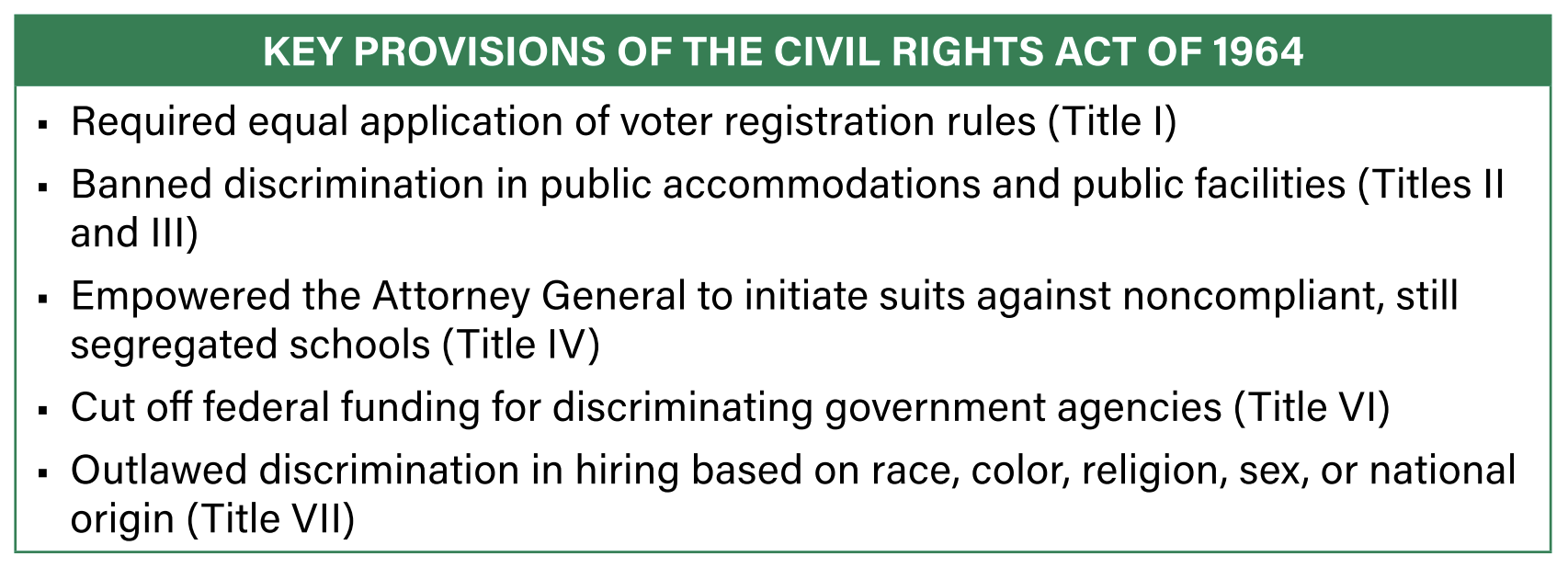

By mid-1963, Kennedy buckled down to battle for a comprehensive civil rights bill. President Kennedy addressed Congress on June 11, 1963, informing the nation of the legal remedies of his proposal. “They involve,” he stated, “every American’s right to vote, to go to school, to get a job, and to be served in a public place without arbitrary discrimination.” Kennedy’s bill became the center of controversy over the next year and became the most sweeping piece of civil rights legislation to date. The proposal barred unequal voter registration requirements and prevented discrimination in public accommodations. It empowered the attorney general to file suits against discriminating institutions, such as schools, and to withhold federal funds from noncompliant programs. Finally, it outlawed discriminatory employment practices.

President Johnson and the 1964 Civil Rights Act

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was slain by a gunman in Dallas. Within an hour, Vice President Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) of Texas was sworn in as the 36th president. Onlookers and black leaders wondered how the presidential agenda might change. Johnson had supported the 1957 Civil Rights Act but only after he moderated it. Civil rights leaders hadn’t forgotten Johnson’s southern roots or the fact that he and Kennedy had not seen eye to eye.

Fortunately, President Johnson took up the fight. “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory,” Johnson stated to the nation, “than the earliest passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long. Days later, on Thanksgiving, Johnson promoted the bill again: “For God made all of us, not some of us, in His image. All of us, not just some of us, are His children.”

Johnson was a much better shepherd for this bill than Kennedy. Johnson, having been a leader in Congress, was skilled at both negotiation and compromise. He had a better chance to gain support for legislation as the folksy, towering Texan than Kennedy had as the elite, overly polished Ivy League patriarch. Johnson was notorious for “the treatment,” an up close and personal technique of muscling lawmakers into seeing things his way. Johnson beckoned lawmakers to the White House for close face-to-face persuasion that some termed “nostril examinations.”

With LBJ’s support, the bill had a favorable outlook. On February 10, after the House had debated for less than two weeks and with a handful of amendments, the House passed the bill 290 to 130. The fight in the Senate was much more difficult. A total of 42 senators added their names as sponsors of the bill. Northern Democrats, Republicans, and the Senate leadership formed a coalition behind the bill that made passage of this law possible. After a 14-hour filibuster by West Virginia’s Robert C. Byrd, a cloture vote was finally taken. The final vote came on June 19 when the civil rights bill passed by 73 to 27, with 21 Democrats and six Republicans in dissent.

The ink from Johnson’s signature was hardly dry when a Georgia motel owner refused service to African Americans and challenged the law. He claimed it exceeded Congress’s authority and violated his constitutional right to operate his private property as he saw fit. In debating the bill, Congress had asserted that its power over interstate commerce granted it the right to legislate in this area. Most of this motel’s customers had come across state lines. By a vote of 9:0, the Court in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States (1964) agreed with Congress.

In April 2014, President Barack Obama gave a speech at a ceremony in Austin, Texas, in honor of the 50th anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Obama reminded listeners that LBJ himself had grown up in poverty, that he had seen the struggles of Latino students in the schools where he taught, and that he pulled those experiences and his prodigious skills as a politician together to pass this landmark law. “Because of the laws President Johnson signed,” Obama said, “new doors of opportunity and education swung open . . . Not just for blacks and whites, but also for women and Latinos and Asians and Native Americans and gay Americans and Americans with a disability. … And that’s why I’m standing here today.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which investigates allegations of discrimination in hiring and firing. The law helped set the stage for passage of an immigration reform bill in 1965, which did away with national origin quotas and increased the diversity of the U.S. population. Senator Hubert Humphrey said before the bill’s passage: “We have removed all elements of second-class citizenship from our laws by the Civil Rights Act. We must in 1965 remove all elements in our immigration law which suggest there are second-class people.”

Instruction in schools in students’ first language, even if it is not English, relates back to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of national origin. The Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, was modeled on the 1964 law and forbade discrimination in public accommodation on the basis of disability. Cases in the news today—from transgender use of bathrooms to wedding cakes for a same-sex couple—relate back to the bedrock provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Impact on Women’s Rights

Successes for African American rights in the 1960s led the way for women to make gains in the following decade. Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, which amended the 1964 Civil Rights Act, guaranteed that women have the same educational opportunities as men in programs receiving federal government funding. Two congresswomen, Patsy Mink (D-HI) and Edith Green (D-OR), introduced the bill, which passed with relative ease.

The law states, “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” This means colleges must offer comparable opportunities to women. Schools don’t have to allow females to join football and wrestling teams—though some have—nor must schools have precisely the same number of student athletes from each gender. However, any school receiving federal dollars must be cognizant of the pursuits of women in the classroom and on the field and maintain gender equity.

To be compliant with Title IX, colleges must make opportunities available for male and female college students in substantially proportionate numbers based on their respective full-time undergraduate enrollment. Additionally, schools must try to expand opportunities and accommodate the interests of the underrepresented sex.

The controversy over equality, especially in college sports, has created a conundrum for many who work in the field of athletics. Fair budgeting and maintaining programs for men and women that satisfy the law has at times been difficult. Some critics of Title IX claim female interest in sports simply does not equal that of young men and, therefore, a school should not be required to create a balance. In 2005, the Office of Civil Rights began allowing colleges to conduct surveys to assess student interest among the sexes. Title IX advocates, however, compare procedures like these to the burden of the freedom-of-choice option in the early days of racial integration. Federal lawsuits have resulted in courts forcing Louisiana State University to create women’s soccer and softball teams and requiring Brown University to maintain school-funded varsity programs for girls.

In 1972, about 30,000 women competed in college varsity-level athletics. Today, more than five times that many do. When the U.S. women’s soccer team won the World Cup championship in 1999, President Clinton referred to them as the “Daughters of Title IX.”

Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Franchise

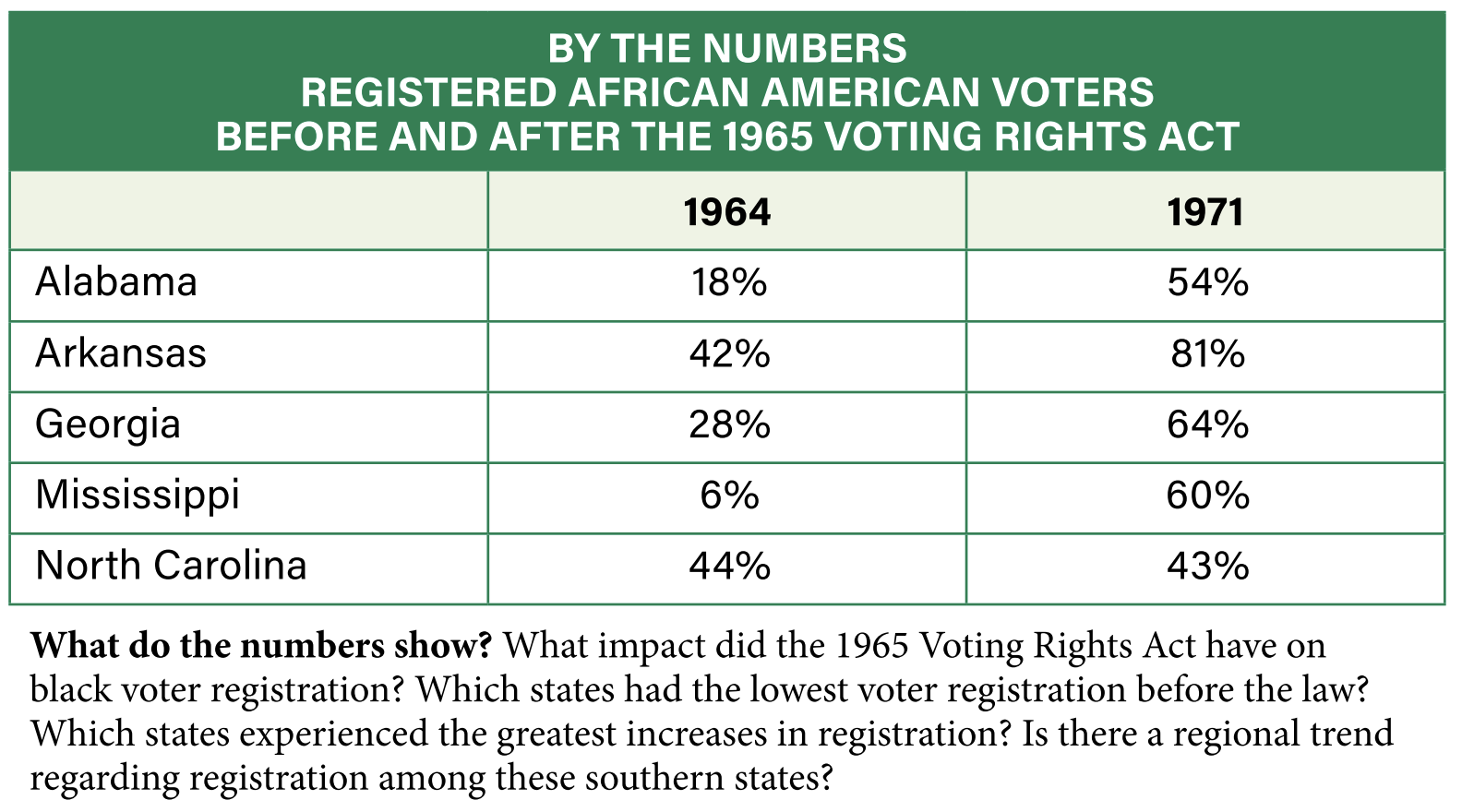

The 1964 Civil Rights Act addressed discrimination in voting registration but lacked the necessary provisions to fully guarantee African Americans the vote. Before World War II, about 150,000 black voters were registered throughout the South, about 3 percent of the region’s black voting-age population. In 1964, African American registration in the southern states varied from 6 to 66 percent but averaged 36 percent.

The Twenty-fourth Amendment, passed in 1962 and ratified by January 1964, outlawed the poll tax in federal elections, primaries, and general elections. At the time of its passage, only five states still imposed such a tax. While it did not abolish taxes for voting at the state or local levels, the Supreme Court’s decision in Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections in 1966 declared such taxes unconstitutional across all levels of elections.

Citizen Protest in Selma

Despite the dismantling of many loopholes to the Fifteenth Amendment, barriers like intimidation and literacy tests continued to suppress African American voter registration. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. focused national attention on Selma, Alabama, where African Americans constituted about half the population but only 1% were registered voters. In protest, King organized a march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital. Alabama state troopers violently blocked the marchers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, employing mounted police and tear gas against the peaceful demonstrators. The brutal incident, known as “Bloody Sunday,” resulted in the deaths of two northern activists.

The media’s coverage of the event galvanized public support for civil rights. President Lyndon B. Johnson, having won a resounding victory in the 1964 presidential election with a Democratic majority in Congress, seized the moment. In a televised address to Congress, Johnson introduced his Voting Rights Act, culminating with the iconic declaration, “We shall overcome.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965

Signed into law on August 6, 1965, exactly 100 years after the end of the Civil War, the Voting Rights Act passed more smoothly than the 1964 Civil Rights Act. This legislation empowered Congress and the federal government to oversee elections in southern states, particularly those using discriminatory “tests or devices” to restrict voter qualifications or with low voter registration rates. The Act effectively ended the use of literacy tests and other barriers that disenfranchised African American voters, marking a significant milestone in the struggle for civil rights in the United States.

The law also required these states to ask for preclearance from the U.S. Justice Department before they could enact new registration policies. If southern states attempted to invent new, creative loopholes to diminish black suffrage, the federal government could stop them.

A constitutional democracy, such as the United States, is founded on the concept of majority rule. Without protections of minority rights, tyranny and oppression can develop. The framers saw the need for upholding the will of the people while still preventing possible abuses of power. When tension between those with power and those without power arises, the court system is often left to determine whose rights will be protected.

Desegregation

During and after Reconstruction, policymakers continued to draw lines between the races. They separated white and black citizens on public carriers, in public restrooms, in theaters, and in public schools. Jim Crow laws (see Topic 3.11) had become the accepted practice in many southern states to guarantee segregation.

“Separate but Equal”

Institutionalized separation was tested in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

Challenging Louisiana’s separate coach law, Homer Adolph Plessy, a man with one-eighth African blood and thus subject to the statute, sat in the white section of a train. He was arrested and convicted and then appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court. His lawyers argued that separation of the races violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause.

The Supreme Court saw it differently, however, and sided with the state’s right to segregate the races in public places, claiming “separate but equal” facilities satisfied the amendment. One lone dissenter, Justice John Marshall Harlan, decried the decision (as he had in the Civil Rights Cases) as a basic violation of the rights of freed African Americans. Harlan’s dissent was only a minority opinion. Segregation and Jim Crow continued for two more generations.

Fulfilling the Spirit of Brown

The Brown v. Board of Education decision overturned the separate but equal doctrine and started desegregating schools in the 1950s and early 1960s. Soon, interest groups and civil rights activists questioned the effectiveness of the Brown decision on schools across the nation. The ruling met with varying degrees of compliance from state to state and from school district to school district. Activists and civil rights lawyers took additional cases to the Supreme Court to ensure both the letter and the spirit of the Brown ruling. From 1958 until the mid-1970s, a series of lawsuits – most filed by the NAACP and most resulting in unanimous pro-integration decisions – brought greater levels of integration in the South and in cities in the North.

The Brown ruling and the Brown II clarification spelled out the Court’s interpretation of practical integration, but a variety of reactions followed. The so-called “Little Rock Nine” – African American students who would be the first to integrate their local high school – faced violent confrontations as they entered school on their first day at Central High School in 1957. School officials and the state government asked for a delay until tempers could settle and until a safer atmosphere would allow for smoother integration. The NAACP countered in court and appealed this case to the high bench. In Cooper v. Aaron (1958), the Court ruled potential violence was not a legal justification to delay compliance with Brown.

In other southern localities, school administrators tried to weaken the impact of the desegregation order by creating measures such as freedom-of-choice plans that placed the transfer burden on black students seeking a move to more modern white schools. Intimidation too often prevented otherwise willing students to ask for a transfer. In short, “all deliberate speed” had resulted in deliberate delay. In 1964, only about one-fifth of the school districts in the previously segregated southern states taught whites and blacks in the same buildings. In the Deep South, only 2 percent of the black student population had entered white schools. And in many of those instances, there were only one or two token black students who had to stand up to an unwelcoming school board and face intimidation from bigoted whites. Rarely did a white student request a transfer to a historically black school. Clearly, the intention of the Brown ruling had been thwarted.

Balancing Enrollments

By the late 1960s, the Court ruled the freedom-of-choice plans, by themselves, an unsatisfactory remedy for integration. The Supreme Court addressed a federal district judge’s solution to integrate a North Carolina school district in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971). The judge had set a mathematical ratio as a goal to achieve higher levels of integration. The district’s overall white-to-black population ratio was roughly 71 to 29 percent. The district judge ordered the school district to assign students to schools across the district to roughly reflect the same proportion of black-to-white student enrollment in each building. The Supreme Court later approved his decision and thus sanctioned mathematical ratios to achieve school integration in another unanimous decision.

The Swann opinion ended a generation of litigation necessary to achieve integration, but it did not end the controversy. A popular movement against busing for racial balance sprang up as protesters questioned the placement of students at distant schools based on race. Though the constitutionality of busing grew out of a southern case, cases from Indianapolis, Dayton, Buffalo, Detroit, and Denver brought much protest. Those protests included efforts to sabotage buses as well as seek legal means to stop similar rulings. The antibusing movement grew strong enough to encourage the U.S. House of Representatives to propose a constitutional amendment to outlaw busing for racial balance, though the Senate never passed it. White parents in scores of cities transferred their children from public schools subject to similar rulings or relocated their families to adjacent suburban districts to avoid rulings. This situation, known as white flight, became commonplace as inner cities became blacker and the surrounding suburbs became whiter.

In an attempt to mandate racial integration across adjacent districts, the NAACP tried to convince the Supreme Court to approve a multidistrict integration order from the Detroit area that otherwise followed the Swann model. The Court stopped short of approving this plan (by a close vote of 5:4) in its 1974 ruling in the Detroit case of Milliken v. Bradley, noting that if the district boundaries were not drawn for the purpose of racial segregation, interdistrict busing is not justified by the Brown decision. In his dissent, former NAACP attorney and then current justice on the Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall wrote, “School district lines, however innocently drawn, will surely be perceived as fences to separate the races when . . . white parents withdraw their children from the Detroit city schools and move to the suburbs in order to continue them in all-white schools.”

Electoral Balance

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (see Topic 3.11) was the single greatest improvement for African Americans’ access to the ballot box. By 1967, black voter registration in six southern states had increased from about 30 to more than 50 percent. African Americans soon held office in greater numbers. Within five years of the law’s passage, several states saw marked increases in their numbers of registered voters. The original law expired in 1971, but Congress has renewed the Voting Rights Act several times, most recently in 2006.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 further requires that voting districts not be drawn in such a way as to “improperly dilute minorities voting power.” The Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles (1982) determined that recently drawn districts in North Carolina “discriminated against blacks by diluting the power of their collective vote, and the Court established criteria for determining whether vote dilution has occurred. The Court also ruled that majority-minority districts-voting districts in which a minority race or group of minorities make up the majority-can be created to redress situations in which African Americans were not allowed to participate fully in elections, a right secured by the Voting Rights Act.

Over time, as the makeup of the Court changed, the Court has revised its position. The Court ruled in 1993 in Shaw v. Reno that if redistricting is done on the basis of race, the actions must be held to strict scrutiny in order to meet the requirement of the equal protection clause, yet race must also be considered to satisfy the requirements of the Voting Rights Act, bringing into question the “colorblind” nature of the Constitution. Justice Blackmun, in his dissent to Shaw v. Reno, noted that “[it is particularly ironic that the case in which today’s majority chooses to abandon settled law … is a challenge by white voters to the plan under which North Carolina has sent black representatives to Congress for the first time since Reconstruction.”

The Court once again interpreted the law, upholding the rights of the majority, in its 2017 ruling in Cooper v. Harris, by determining that districts in North Carolina were unconstitutionally drawn because they relied on race as the dominant factor.