Cases:

Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925)

Griswold v. Connecticut (1925)

Roe v. Wade *overturned by: Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022)

Need to know:

implicit right

enumerated right

penumbra of explicit rights

The framers didn’t explicitly state that citizens have a “right to privacy” in the Constitution. This idea of a “right to be left alone” or a right to privacy can be pulled from the wording of several amendments. The First Amendment deals with the privacy of one’s thoughts or associations with others. The Third protects the privacy of one’s home by limiting when government can house soldiers there. The Fourth protects against illegal searches, keeping a home or other area (purses, lockers) private. The Fifth entitles an accused defendant to refrain from testifying and thus to keep information private. Also, the Ninth Amendment is a cautionary limit to the power of the federal government in general, stating that people have rights not specifically listed, perhaps privacy.

Substantive Due Process

Substantive due process protects fundamental liberties so basic that they may not be expressed in the Constitution. Unlike procedural due process, which assures procedures related to fairness and liberty like jury selection or reading arrested suspects their rights -substantive due process is invoked when the very substance, or purpose, of the law violates fundamental rights.

The Supreme Court and lower courts have referred to the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause to assure states are protecting substantive due process. State government policies that might violate substantive due process rights must meet some valid state or public interest to promote the police powers of regulating health, welfare, or morals. The right to substantive due process protects people from policies for which no such legitimate state interest exists or when state interest fails to override the citizens’ rights. The Supreme Court has ruled on laws limiting how much an employee can work, requiring public school attendance, and restricting abortion as violations of substantive due process.

Substantive Due Process Defined

The 1873 Slaughterhouse Cases forced a decision on the privileges or immunities clause of the recently ratified Fourteenth Amendment and dealt with a substantive due process issue. The state of Louisiana had consolidated slaughterhouses into one government-run operation outside of New Orleans, causing butchers in other locations across the state to close up shop and thereby infringing on their right to pursue lawful employment. The majority opinion ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment’s privileges or immunities clause protected only those rights related to national citizenship and did not apply to the states, even though the state law in this case limited the butchers’ basic right to pursue lawful employment.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Joseph Bradley asserted “the right of any citizen to follow whatever lawful employment he chooses to adopt … is one of his most valuable rights and one which the legislature of a State cannot invade,” so a law that violates a fundamental, inalienable right cannot be constitutional.

In 1905, the Court ruled on a New York maximum hours statute meant to protect workers. It found the regulation violated “liberty of contract.” In a later decision, Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), the Court ruled that an Oregon law requiring children to be taught in public schools a substantive due process violation.

“The fundamental theory of liberty, the majority opinion states, doesn’t give the state the right to determine who educates the child, but assures “those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right?”

Right to Privacy

Citizens have had expectations of privacy from government for many years. In 1890, progressive lawyer Louis Brandeis made this clear in a Harvard Law Review article. By 1928, Brandeis, now a Supreme Court justice, stamped his views on privacy into the pages of Court opinions. In Olmstead v. United States (1928), the Supreme Court upheld a conviction of a bootlegger discovered by wiretapped phone lines, but Brandeis dissented, and warned of a future where government could invade the most basic citizen privacies.

Into the 1960s, views on civil liberties protections changed. The modern birth control movement led to challenges of laws preventing the practice. In Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), the Supreme Court ruled against a law that barred people, even married couples, from receiving birth control literature. Justice William O. Douglas wrote that the right to privacy can be found in the “penumbras,” or shadows, of the Bill of Rights as explained in this topic’s opening paragraph.

Two years later, the Court reversed the Olmstead ruling. In that case, the FBI had recorded gambling conversations at a public pay phone frequented by a suspected bookmaker. Even though the listening device was placed outside the phone booth, the Court ruled the recorded conversations inadmissible at trial because “the Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person … seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected.” The police and FBI can still wiretap suspects’ phones, but only after a judge has issued a warrant.

Right to Abortion

Abortion law has ebbed and flowed in American jurisprudence. It is the perfect study in judicial restraint versus activism, in state versus federal authority, and in majority rule versus minority rights. For the first several decades of the Republic, no state had criminalized or regulated abortion. In the mid-to-late 1800s, the American Medical Association sought to regulate the practice, and then state and national legislators moved to outlaw abortion.

With the Griswold decision in place and the birth control pill on the market, abortion advocates found a test case when only four states allowed abortion by choice. Norma McCorvey, a pregnant 21-year-old circus worker, sought an abortion in Texas. Supported by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), McCorvey’s lawyer filed suit against local Dallas District Attorney Henry Wade.

To protect McCorvey’s identity, the Court dubbed the plaintiff “Jane Roe” and the case became known as Roe v. Wade. The plaintiff’s lawyers argued that Texas had violated Roe’s “right to privacy” and that it was not the government’s decision to determine a pregnant woman’s medical decision. Texas stood by its authority to regulate health, morals, and welfare under the police powers doctrine.

In 1973, the Supreme Court ruled for Roe 7:2 and stated in its majority opinion, State criminal abortion laws, like those involved here … violate the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects against state action the right to privacy, including a woman’s qualified right to terminate her pregnancy. The Court also expressed that states have a legitimate interest in protecting the potentiality of human life. Among other points, the lengthy opinion assured an unfettered right to abortion during roughly the first trimester of pregnancy.

With Roe, the restrictive abortion statutes of numerous states were essentially erased from law books, but many states acted to limit without outlawing the practice. In 1976, Congress passed the Hyde Amendment, which restricts federal funding for abortions, except for pregnancies caused by incest or rape or those endangering the life of the mother. Abortion advocates sought to dismantle these restrictions in the courts. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Court upheld mandatory waiting periods and parental consent for pregnant minors but struck down an “informed consent” provision requiring the pregnant woman to inform and secure consent from the father.

The Dobbs Decision

The pro-life movement and Republican Supreme Court appointments galvanized efforts to overturn the 1973 ruling. Roe v. Wade became a lightning rod in every election season and a litmus test at every Senate confirmation hearing. After President George W. Bush appointed two conservative, Catholic justices, pro-life advocates increased their efforts. States began drafting more restrictive abortion laws. In 2018, Mississippi’s legislature passed the Gestational Age Act which prohibits all abortions after 15 weeks of pregnancy “except in medical emergency and in cases of severe fetal abnormality.” The sole abortion clinic in Mississippi, Jackson Women’s Health Organization, filed suit against Thomas Dobbs, the state’s chief health officer. When the case arrived at the U.S. Supreme Court, a 6:3 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) overturned Roe. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Alito said “the Constitution does not confer a right to abortion, Roe and Casey must be overruled, and the authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their elected representatives.” Ultimately, this decision allowed states to determine abortion policy.

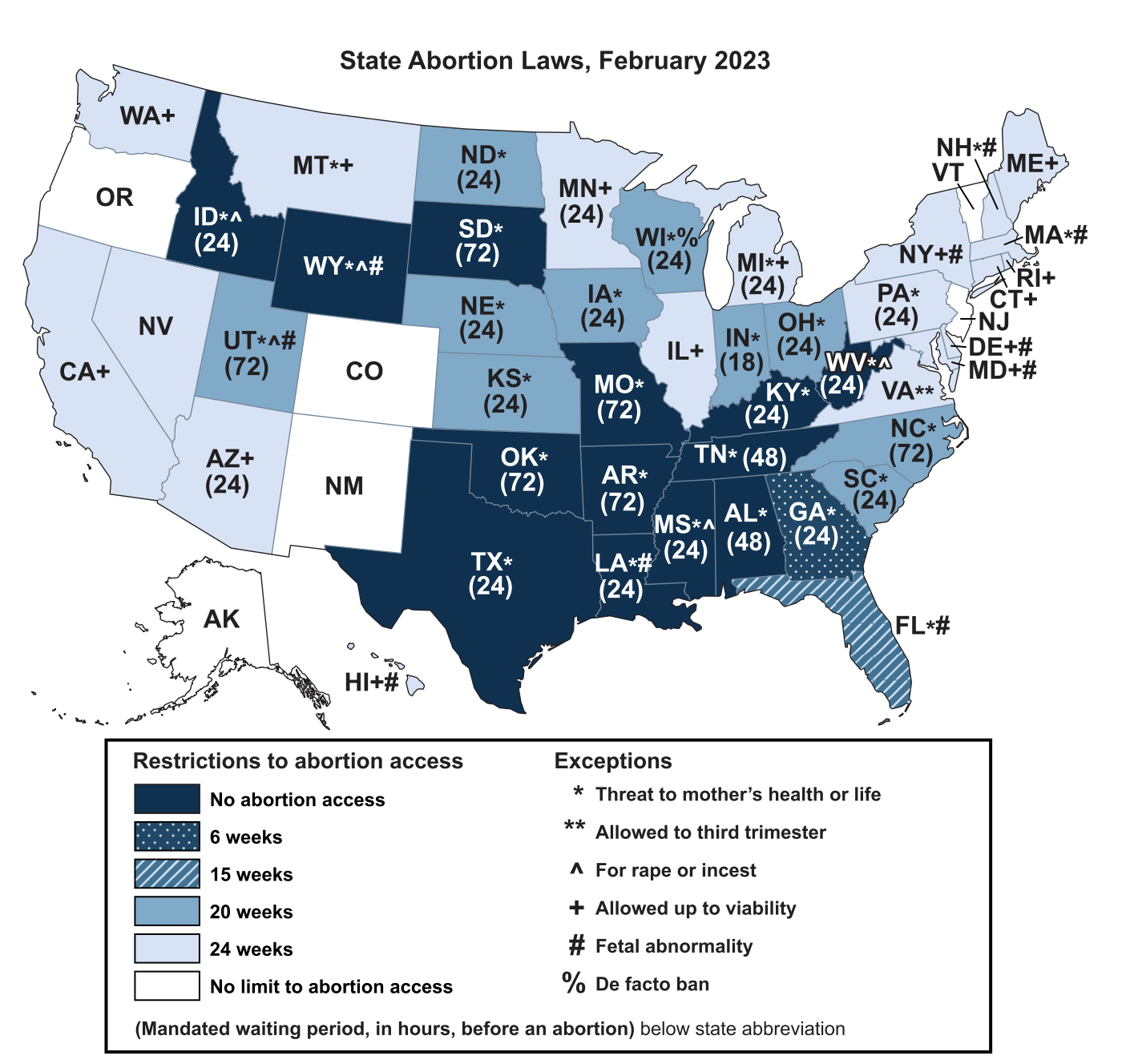

In the months that followed Dobbs, both pro-life and pro-choice activity rose. Thirteen states already had “trigger laws” – statutes on the books that would activate some version of a pre-Roe law if the Supreme Court ever overturned Roe. Several state legislatures have put forth statutes and proposed constitutional amendments to strengthen or restrict abortion rights.

Organizations on both sides have filed cases. The Dobbs decision has reset the national patchwork of abortion laws guided by federalism.