Cases:

Need to Know:

time, place, & manner rule

defamatory, offensive & obscene speech regulations

clear & present danger test

Brandenburg test

substantial disruption test

Espionage Act, 1917

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 states that “governments should not substantially burden religious exercise without compelling justification.” This law was created out of anger at a Supreme Court ruling in the Employment Division v. Smith case in 1990. Both liberals and conservatives disapproved of the ruling because it weakened citizens’ rights to religious practices that conflicted with government statutes. The Supreme Court struck down parts of the RFRA in 1997, stating it infringed on states’ rights, and according to many, weakened Americans right to religious freedom.

Since the RFRA was passed, 31 states have passed similar legislation to protect religious liberty.

Today, the issue of free exercise of religion can collide with the state’s power to assure fairness toward LGBTQ people. For example, can a state through its power to regulate commerce mandate a merchant to serve gay people if doing so conflicts with the merchant’s religious beliefs about homosexuality?

The First Amendment: Church and State

The founders wanted to stamp out religious intolerance and outlaw a nationally sanctioned religion. The Supreme Court did not address congressional action on religion for most of the 1800s, and it did not examine state policies that affected religion for another generation after that. As the nation became more diverse and more secular over the years, the Supreme Court constructed what Thomas Jefferson had called a “wall of separation” between church and state. In this nation of varied religions and countless government institutions, however, church and state can sometimes encroach on each other. Like other interpretations of civil liberties, those addressing freedom of religion are intricate and sometimes confusing. Recently, the Court has addressed laws that regulate the teaching of evolution, the use of school vouchers, and the public display of religious symbols.

Freedom of Religion

Both James Madison and Thomas Jefferson led a fight to oppose a Virginia tax to fund an established state church in 1785. Madison argued that no law should support any true religion nor should any government tax anyone, believer or nonbeliever, to fund a church. During the ratification battle in 1787, Jefferson wrote Madison and expressed regret that the proposed Constitution lacked a Bill of Rights, especially an expressed freedom of religion. The First Amendment allayed these concerns because it reads in part, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” In 1802, President Jefferson popularized the phrase “separation of church and state” after assuring Baptists in Danbury, Connecticut, that the First Amendment builds a “wall of separation between church and state.” Today some citizens want a stronger separation; others want none.

Members of the First Congress included the establishment clause in the First Amendment to prevent the federal government from establishing a national religion. More recently, the clause has come to mean that governing institutions-federal, state, and local-cannot sanction, recognize, favor, or disregard any religion. The free exercise clause in the First Amendment prevents governments from stopping religious practices. This clause is generally upheld, unless a religious act is illegal or threatens the interests of the community. Today, these clauses collectively mean people can practice any religion they want, provided it doesn’t violate established law or harm others, and the state cannot endorse or advance one religion over another. The Supreme Court’s interpretation and application of the establishment clause and free exercise clause show a commitment to individual liberties and an effort to balance the religious practice of majorities with the right to the free exercise of minority religious practices or no religious practices.

The Court Erects a Wall

In the 1940s, New Jersey allowed public school boards to reimburse parents for transporting their children to school, even if the children attended parochial schools—those maintained by a church or religious organization. Some argued this constituted an establishment of religion, but in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Court upheld the law. State law is not meant to favor or handicap any religion. This law gave no money to parochial schools but instead provided funds evenly to parents who transported their children to the state’s accredited schools, whether religious or public. Preventing payments to parochial students’ parents would create an inequity for them. Much like fire stations, police, and utilities, school transportation is a nonreligious service available to all taxpayers.

Though nothing changed with Everson, the Court did signal that the religion clauses of the First Amendment applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment in the selective incorporation process. The Court also used Jefferson’s phrase in its opinion and began erecting the modern wall of separation.

Prayer in Public Schools

In their early development, public schools were largely Protestant institutions that began their day with a prayer. But the Court outlawed the practice in the early 1960s in its landmark case, Engel v. Vitale (1962). A year later, in School District of Abington Township, Pennsylvania v. Schempp, the Court outlawed a daily Bible reading in the Abington schools in Pennsylvania and thus in all public schools. In both cases, the school had projected or promoted religion, which constituted an establishment.

The Lemon Test

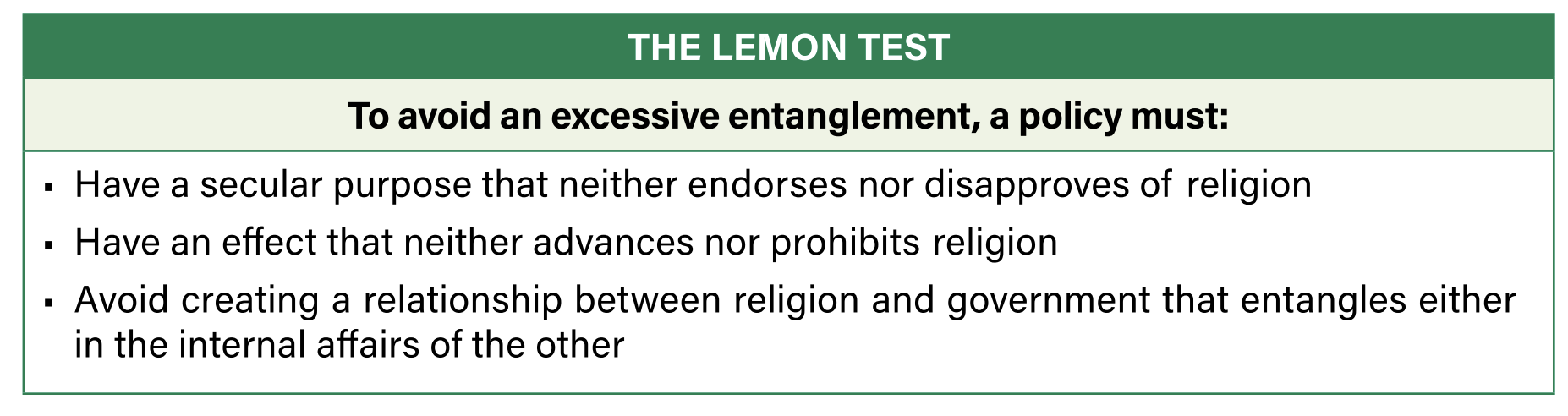

In 1971, the Court created a measure of whether or not the state violated the establishment clause in Lemon v. Kurtzman. Rhode Island and Pennsylvania passed laws to pay teachers of secular subjects in religious schools with state funds. The states mandated such subjects as English and math and reasoned that it should assist the parochial schools in carrying out a state requirement. In trying to determine the constitutionality of this statute, the Court decided these laws created an “excessive entanglement” between the state and the church because teachers in these parochial schools may improperly involve faith in their teaching.

In the unanimous opinion, Chief Justice Warren Burger further articulated Jefferson’s “wall of separation” concept, and “far from being a ‘wall,’ the policy made a blurred, indistinct, and variable barrier.” To guide lower court decisions and future controversies that might reach the High Court, the justices in the case of Lemon v. Kurtzman developed the Lemon test to determine excessive entanglement.

Education and the Free Exercise Clause

In 1972, the Court ruled that a Wisconsin high school attendance law violated Amish parents’ right to teach their own children under the free exercise clause. The Court found that the Amish’s alternative mode of informal vocational training paralleled the state’s objectives. Requiring these children to attend high school violated the basic tenets of the Amish faith because it forced their children into unwanted environments.

Contemporary First Amendment Issues

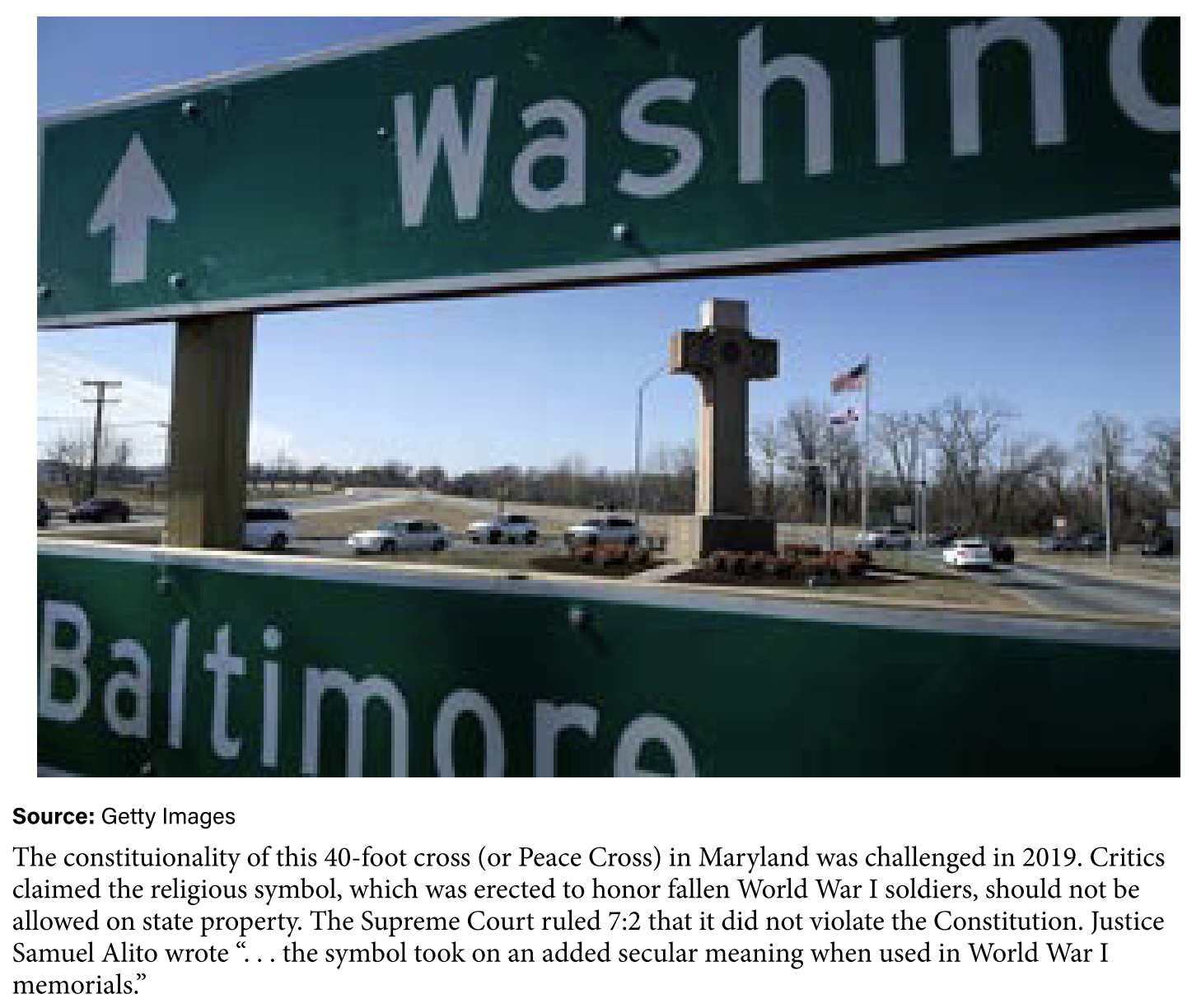

Real and perceived excessive entanglements between church and state continue to make the news today. Can government funding go to private schools or universities at all? Does a display of religious symbols on public grounds constitute an establishment of religion? As with so many cases, it depends.

Public Funding of Religious Institutions

Many establishment cases address whether or not state governments can contribute funds to religious institutions, especially Roman Catholic schools. Virtually every one has been struck down, except those secular endeavors that aid higher education in religious colleges, perhaps because state laws do not require education beyond the twelfth grade and older students are not as impressionable.

Vouchers

Supporters of private parochial schools and parents who pay tuition argue that the government should issue vouchers to ease their costs. Parents of parochial students pay the same taxes as public school parents while their children don’t receive the services of public schools. A Cleveland, Ohio, program offered as much as $2,250 in tuition reimbursements for low-income families and $1,875 for any families sending their children to private schools. The Court upheld the program largely because the policy did not make a distinction between religious or nonreligious private schools, even though 96 percent of private school students attended a religious-based school. This money did not go directly to the religious schools but rather to the parents for educating their children.

Religion in Public Schools

Since the Engel and Abington decisions, any formal prayer in public schools and even a daily, routine moment of silence are considered violations of the establishment clause. The Court has even ruled against student-led prayer at official public school events. However, popular opinion has never endorsed these stances. In 2014, Gallup found that 61 percent of Americans supported allowing daily prayer, down from 70 percent in 1999.

Students can still operate extracurricular activities of a religious nature provided these take place outside the school day and without tax dollars. The free exercise clause guarantees students’ rights to say private prayers, wear religious T-shirts, and discuss religion. Public teachers’ actions are more restricted because they are employed by the state.

Religious Symbols in the Public Square

Pawtucket, Rhode Island, annually adorned its shopping district with Christmas decor, including a Christmas tree, a Santa’s house, and a nativity scene. Plaintiffs sued, arguing that the nativity scene created government establishment of Christianity. In Lynch v. Donnelly (1984), the Court upheld the city’s right to include this emblem because it served a legitimate secular purpose of depicting the historical origins of the Christmas holiday. In another case in 1989, the Court found the display of a crèche (manger scene) on public property, when standing alone without other Christmas decor, a violation because it was seen as a Christian-centered display.

Ten Commandments

In 2005, the Court ruled two different ways on the issue of displaying the Ten Commandments on government property. One case involved a large outdoor display at the Texas state capitol. Among 17 other monuments sat a six-foot-tall rendering of the Ten Commandments. The other case involved the Ten Commandments hanging in two Kentucky courthouses, accompanied by several historical American documents. The Court said the Texas display was acceptable because of the monument’s religious and historical function. It was not in a location that anyone would be compelled to be in, such as a school or a courtroom. And it was a passive use of the religious text in that only occasional passersby would see it. The Kentucky courtroom case brought the opposite conclusion because an objective observer would perceive the displays as having a predominantly religious purpose in state courtrooms—places where some citizens must attend and places meant to be free from prejudice.