Need to Know:

time, place, & manner rule

defamatory, offensive & obscene speech regulations

clear & present danger test

Brandenburg test

substantial disruption test

Espionage Act, 1917

Freedom of speech is one of the cherished liberties in the First Amendment.

Freedom of speech issues extend much further than just the words that come out of an individual’s mouth. This right can inspire passionate arguments to protect and to limit speech depending on its content. The Supreme Court has ruled on this right many times. The Court’s interpretations relate to topics like offensive or obscene speech, protest speech, symbolic speech, and the right not to “speak.”

Defining Protected Speech

The Supreme Court has taken two generations of cases to define “free speech” and “free press,” and free speech cases still occasionally appear on the Court’s docket. When does one person’s right to free expression violate others’ right to peace, safety, or decency? Free speech is not absolute, but both federal and state governments have to show substantial or compelling governmental interest-a purpose important enough to justify the infringement of personal liberties- to curb it.

The creators of the First Amendment meant to prevent government censorship. Many revolutionary leaders came to despise the accusation of seditious libel-a charge that resulted in fines and/or jail time for anyone who criticized public officials or government policies. Expressing dissent in assemblies and in print during the colonial era led to independence and increased freedoms, therefore, members of the first Congress preserved this right as the very first of the amendments.

Time, Place, and Manner Regulations

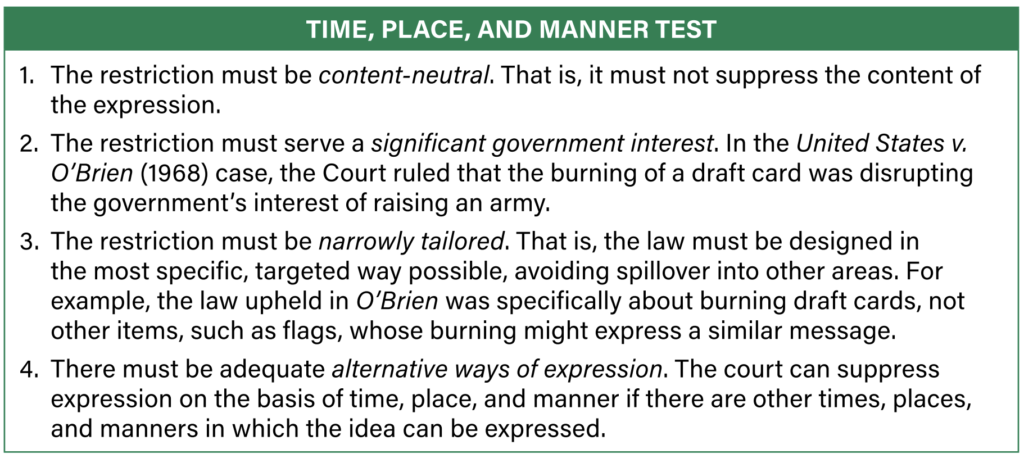

In evaluating regulations of symbolic expression, the Court looks primarily at whether the regulation suppresses the content of the message or simply regulates the accompanying conduct. Is the government ultimately suppressing what was being said, or the time, place, or manner in which it was expressed?

Era of Protest The 1960s witnessed a revolution in free expression. As support for the Vietnam War waned, young men burned their draft cards to protest the military draft. Congress quickly passed a law to prevent the destruction of these government-issued documents.

David O’Brien burned his Selective Service registration card in front of a Boston courthouse and was convicted for that action under the Selective Service Act, which prohibited willful destruction of draft cards.

He appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that his protest was a symbolic act of speech that government could not infringe. The Court, however, upheld his conviction and sided with the government’s right to prevent this behavior in order to protect Congress’s authority to raise and support an army. O’Brien was disrupting the draft effort and publicly encouraging others to do the same. Others continued to burn draft cards, but after United States v. O’Brien (1968), this symbolic act was not protected.

In April 1968, Paul Robert Cohen wore a jacket bearing the words “F–k the Draft” while walking into a Los Angeles courthouse. Local authorities arrested and convicted him for “disturbing the peace . .. by offensive conduct? The Supreme Court later overturned the conviction in Cohen v. California (1971). The phrase on the jacket in no real way incited an illegal action. “One man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric” the majority opinion stated.

Compare the Cohen and O’Brien rulings. In both cases, someone expressed opposition to the Vietnam-era draft. O’Brien burned a government-issued draft card. ‘The Court didn’t protect the defendant’s speech but rather upheld a law to assist Congress in its conscription powers. Cohen publicly expressed dislike for the draft with an ugly phrase printed on his jacket, but he did nothing to incite public protest and did not refuse to enlist, so the Court protected the speech.

Time, place, and manner regulations must be tested against a set of four criteria.

The question of “place” and “manner” became key aspects of a landmark case involving free speech in schools in Tinker v. Des Moines.

Symbolic Speech

People cannot invoke symbolic speech to defend an act that might otherwise be illegal. For example, a nude citizen cannot walk through the town square and claim a right to symbolically protest textile sweatshops after his arrest for indecent exposure. Symbolic speech per se is not an absolute defense in a free speech conflict. However, the Court has protected a number of symbolic acts or expressions.

The Court struck down both state and federal statutes meant to prevent desecrating or burning the U.S. flag in Texas v. Johnson (1989) and United States v. Eichman (1990), respectively. The Court found that these laws serve no purpose other than ensuring a government-imposed political idea – reverence for the flag.

Obscenity

Some language and images are so offensive to the average citizen that governments have banned them. Though obscenity is difficult to define, two trends prevail regarding obscene speech: The First Amendment does not protect it, and no national standard fully defines it.

In the 19th century, some states and later the national government outlawed obscenity. Reacting to published birth control literature, postal inspector and moral crusader Anthony Comstock pushed for the first national anti-obscenity law in 1873, which banned the circulation and importation of obscene materials through the U.S. mail. Yet the legal debate since has generally been over state and local ordinances brought before the Supreme Court on a case-by-case basis. The Court has tried to square an individual’s right to free speech or press and a community’s right to ban obscene and offensive material.

A Transformational Time

From the late 1950s until the early 1970s, the Supreme Court heard several appeals by those convicted for obscenity. In Roth v. United States (1957), Samuel Roth, a long-time publisher of questionable books, was prosecuted under the Comstock Act. He published and sent through the mail his Good Times magazine, which contained partially airbrushed nude photographs. On the same day, the Court heard a case examining a California obscenity law. The Court upheld the long-standing view that both state and federal obscenity laws were constitutionally permissible because obscenity is “utterly without redeeming social importance.” In Roth, the Court defined speech as obscene and unprotected when “the average person, applying contemporary community standards,” finds that it “appeals to the prurient interest” (lustful or lewd thoughts or wishes).

Defining Obscenity

The new rule created a swamp of ambiguity that the Court tried to clear during the next 15 years. Before Roth finished his prison term, the law turned in his favor. The pornography industry grew apace during the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. States reacted, creating a battle between those declaring a constitutional right to create or consume risqué materials and local governments seeking bans. The Court struggled to determine this balance. In his frequently quoted phrase from a 1964 case regarding how to distinguish acceptable versus unacceptable pornographic images or expression, Justice Potter Stewart said, “I know it when I see it.” Although the Court could not reach a solid definition of obscenity, from 1967 to 1971, it overturned 31 obscenity convictions.

The conflict continued with Miller v. California (1973). After a mass mailing from Marvin Miller promoting adult materials, a number of recipients complained to the police. California authorities prosecuted Miller under the state’s obscenity laws. On appeal, the justices reaffirmed that obscene material was not constitutionally protected, but they modified the Roth decision, stating that a local judge or jury should define obscenity by applying local community standards. Obscenity is not necessarily the same as pornography, and pornography may or may not be obscene. The Court has heard subsequent cases dealing with obscene speech, but the Miller Test—a set of three criteria that resulted from the Miller case—has served as the standard in obscenity cases.

Balancing National Security and Individual Freedoms

The Supreme Court continually interprets provisions of the Bill of Rights to balance the power of government and the civil liberties of individuals, sometimes recognizing that individual freedoms are of primary importance and at other times finding that limitations to free speech can be justified, especially when needed to maintain social order.

Clear and Present Danger

The first time the Court examined a federal conviction on a free speech claim was in Schenck v. United States, 1919. This case helped establish that limitations on free speech may be warranted during wartime.