Understand The Following:

1. The views of the federalists and antifederalist in regards to a Bill of Rights, and their arguments and reasoning.

2. The application of the Bill of Rights/Constitution to the federal government vs state governments.

3. How the court has balanced the protection of individual freedom/liberty with the need for public safety and order.

Bill of Rights

1st Amendment – 10th Amendment

Balancing Freedom & Order

Examples:

8th Amenment

2nd Amendment

4th Amendment

Americans have held liberty in high regard, in part due to the violation of several fundamental liberties by British authorities. The original Constitution includes a few basic protections from government-Congress can pass no bill of attainder and no ex post facto law and cannot suspend habeas corpus rights in peacetime. Article III guarantees a defendant the right to trial by jury. However, the original Constitution lacked many fundamental protections, so critics and Anti-Federalists pushed for a bill of rights to protect civil liberties- those personal freedoms protected from arbitrary governmental interference or deprivations by constitutional guarantee.

Liberties and the Constitution

James Madison originally opposed adding a bill of rights to the proposed Constitution. Madison felt it was unnecessary, believing that the Constitution clearly diluted powers of the government into the three branches, greatly diminishing any chance government would run over citizen rights. The checks and limitations already in the Constitution, he argued, would remove the need for a specific listing of rights. Additionally, if such a new document listed all the rights that the government cannot take away, any rights not listed might be vulnerable to government overreach. An incomplete list would create danger to liberty in years to come.

James Madison’s Role

One of the main debates between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists was over a bill of rights. Several delegates at the state-ratifying conventions voted against ratification on this point. Others voted conditionally or expressed a general acceptance of the Constitution in spite of this deficiency. As the debate continued after the ninth and requisite state ratified the original document, Madison’s opinion began to change. When Congress opened in 1789, Madison served in the brand-new House of Representatives.

Considering the complaints and suggestions of Anti-Federalists, including essays in the newspapers at the time and formal petitions from the states, he narrowed down dozens of points of law into twelve formal rights. Congress agreed and sent these rights to the states for ratification. One of the first major pieces of legislation enacted by the new republic was the ratification process.

In the end, ten of Madison’s amendments were added to the Constitution in 1791. The Father of the Constitution and original critic of this rights plan had become the Father of the Bill of Rights.

Protections in the Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights was designed specifically to guarantee liberties and rights. These civil liberties include protections of citizens thoughts, beliefs, opinions, and their right to express them. It protects property. Government cannot take away property without a just cause. A list of criminal justice rights embedded in the Bill of Rights guarantees a criminal defendant protection against government searches unless with probable cause; a right to cross-examine witnesses, to refuse to testify, and to be judged by a jury of peers; and protection against cruel and unusual punishment.

Madison and his new congressional colleagues included two disclaimers at the end of the list. The Ninth Amendment states there are rights that are protected and cannot be denied by the government, even those not explicitly listed in the Bill of Rights. The Tenth Amendment codifies an understanding from Philadelphia in 1787 and throughout the ratification debate on the proposed Constitution: All powers delegated to the federal government are expressly listed, and those that are not listed remain with the states.

Fear of a Central Government

Specifically, individuals were protected from the federal government and “misconstruction or abuse of its powers, according to the Preamble of the Bill of Rights. That list of protections did not originally apply to state governments. It did not prevent states from entangling church and government nor from taking private property for public use. Some states had laws on the books that required major officeholders to be members of a church. However, for the most part, state constitutions and common values across the country upheld the protections in the Bill of Rights. But in a landmark case, Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the Supreme Court said those protections didn’t have to be guaranteed by the states. This precedent remained until the selective incorporation doctrine began to develop and was applied by the Supreme Court in the 20th century.

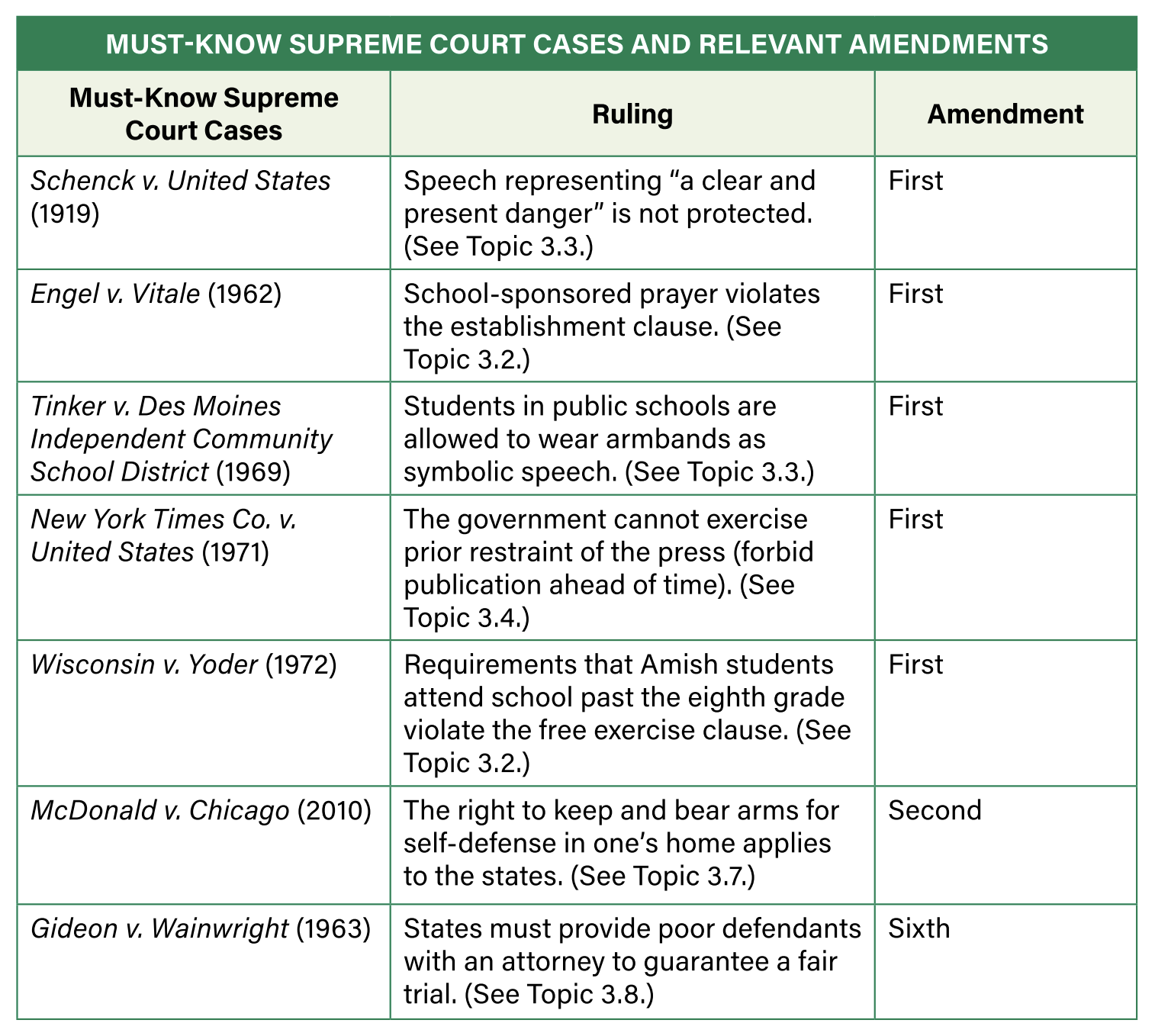

Over the years, the Supreme Court has interpreted the provisions in the Bill of Rights in an effort to balance individual rights with public safety and order. Eight of the fifteen Supreme Court cases to know for the AP exam are tied to the Bill of Rights.

A Culture of Civil Liberties

The freedoms Americans enjoy are about as comprehensive as those in any Western democracy. Anyone can practice or create nearly any kind of religion. Expressing opinions in public forums or in print is nearly always protected. Just outside the Capitol building, the White House, and the Supreme Court, protestors often gather to criticize law, presidential action, and alleged miscarriages of justice without fear of punishment or retribution. Nearly all people enjoy a great degree of privacy in their homes. Unless the police have “probable cause” to suspect criminal behavior, individuals can trust that government will not enter unannounced. When civil liberties violations have occurred, individuals and groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have challenged them in court.

At the same time, however, civil liberties are limited when they impinge on the public interest, another cherished democratic ideal. Public interest is the welfare or well-being of the general public. For example, for the sake of public interest, the liberties of minors are limited. Their right to drive is restricted until they are teenagers (between 14 and 17 years old, depending on their state), both for their safety and the safety of the general public. And although people generally have the right to free speech, what they say cannot seriously threaten public safety or ruin a person’s reputation with untruthful claims. In the culture of civil liberties in the United States, then, personal liberties have limits out of concern for the public interest.

Interpreting the Bill of Rights

The United States has experienced many changes in the more than two centuries it has existed. World wars, economic depressions, industrial revolutions, and social shifts have challenged the flexibility of the Constitution. Whether they are interpreting the Constitution, clarifying the meaning of the amendments, or determining the constitutionality of newly passed laws, the justices on the Supreme Court often dictate the direction of the nation. The Court has interpreted and reinterpreted liberties in an effort to protect them from encroachment by the federal government or local governments.

In addition to the Must-Know Cases in the table above, the Supreme Court has been involved in determining if the government-state or federal-crosses a line and violates a clause in the Bill of Rights. These Supreme Court decisions provide clarity on the law. Whether they permit the state to limit the Bill of Rights in the name of order or declare the government has gone too far and violated citizens rights, these decisions further define civil liberty. Decisions over what exactly constitutes a “fair and impartial jury,” a “speedy trial,” or “excessive bail” have changed over time. These broad phrases enabled the Bill of Rights’ ratification in 1791 but have kept the courts busy over the years. In the process of judicial review and defining these liberties, the courts will continue to clarify the balance between liberties and public order.

While the First and Second Amendments focus on guaranteeing individual liberties in relation to speech, religion, assembly, and bearing arms, other amendments in the Bill of Rights protect minorities and vulnerable populations-those suspected or accused of crimes, the poor, and the indigent-through the due process clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Constitutional provisions also help guide conflicts between individual liberties and national security concerns. Those conflicts can range from the Second Amendment argument of the right of one person to own a gun versus another person’s right to be safe from gun violence to the Fourth Amendment’s protections against illegal searches and seizures versus the government promoting public safety. Governmental laws and policies balancing order and liberty are based on the U.S. Constitution and have been interpreted differently over time.

Cruel and Unusual Punishments and Excessive Bail

The phrases decrying and preventing government from applying “cruel and unusual punishments” and requiring “excessive bail” had worked their way into the English Bill of Rights generations before the American Revolution. The colonists who formed the United States saw some of the punishments toward the early critics of the British monarchy during the pre-war period as cruel and unusual. Kings had imprisoned their foes on false charges and denied the possibility for bail. They had also mistreated or starved their foes to death. These actions were likely taken because a fair and public trial probably would not have rendered the guilty verdict the king wanted. In the new republic, the U.S. Bill of Rights would protect against these practices.

Eighth Amendment

‘The Eighth Amendment (1791) prevents cruel and unusual punishments and excessive bail. Capital punishment, or the death penalty, has been in use for most of U.S. history, and it was allowed at the time of ratification of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. (The Fifth Amendment refers to individuals being “deprived of life.) There is nevertheless debate about whether the death penalty fits the definition, according to the framers, of cruel and unusual. A handful of U.S. states, as well as most Western and developed countries, have banned the practice.

States can use a variety of methods of execution; lethal injection is the most common. From 1930 through the 1960s, 87 percent of death penalty sentences were for murder, and 12 percent were for rape. The remaining 1 percent included treasonous charges and other offenses. In the United States, large majorities have long favored the death penalty for premeditated murders.

The Court put the death penalty on hold nationally with the decision in Furman v. Georgia in 1972. In a complex 5:4 decision, only two justices called the death penalty itself a violation of the Constitution. Justice Brennan wrote that most of society rejects the unnecessary severity of the death penalty, and there are other less severe punishments available. Justice Marshall called the death penalty excessive and served “no legislative purpose.” Also, the Court’s decision addressed the randomness of the application of the death penalty.

Some justices pointed out the disproportionate application of the death penalty to the socially disadvantaged, the poor, and racial minorities.

With the decision of Gregg v. Georgia in 1976, the Court began reinstating the death penalty as states restructured their sentencing guidelines. No state can make the death penalty mandatory by law. Rather, a careful and deliberate look at the circumstances leading to the crime must be taken into account in the penalty phase–the second phase of trial following a guilty verdict. Character witnesses may testify in the defendant’s favor to affect the issuance of the death penalty. In recent years, in cases of murder, the Court has outlawed the death penalty for mentally handicapped defendants and those defendants who were under 18 years of age at the time of the murder.

Guantanamo Bay and Interrogations

After the September 11, 2001, attack on the United States, in 2002 the U.S. military established a detention camp at its naval base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, to hold terror suspects captured in the global war on terror. Placing the camp at this base provided stronger security, minimal media contact, and less prisoner access to legal aid than if it had been within U.S. borders. Administration officials believed that the location of the camp and interrogations outside the United States allowed a loosening of constitutional restrictions. If the suspect never entered the U.S., would he be entitled to constitutional and Bill of Rights provisions?

Soon after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, administration officials signaled that unconventional tactics would be necessary to prevent another devastating attack. In trying to determine the legal limits of an intense interrogation, President Bush’s lawyers issued the now infamous “torture memo.” In August of 2002, President George W. Bush’s Office of Legal Counsel offered the legal definition of torture, calling it “severe physical pain or suffering.” The memo claimed such pain “must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” One of the notorious techniques employed to gather information from reluctant detainees who fit this description was waterboarding-an ancient method that simulates drowning.

As these policies developed and became public, international peace organizations and civil libertarians in the United States questioned the disregard for both habeas corpus rights and the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. The international community, too, was aghast and left wondering, “Do the protections of the Bill of Rights extend to suspected terrorists?”

President Obama reversed many of the Bush administration’s positions regarding torture techniques on terrorism suspects. Many U.S. intelligence officials protested these changes, claiming a need for the flexibility of various techniques to acquire information vital to the nation’s security from detainees.

Individual Rights and the Second Amendment

Attempts to shape gun policy continue at the federal level with little success.

Most gun policy and efforts to balance order and freedom with respect to the Second Amendment are scattered among varying state laws and occasional lower court decisions.

Recent State Policy

About 33,000 American deaths result from handguns each year; roughly one-third are homicides, and two-thirds are suicides. In 2014, about 11,000 of the nearly 16,000 homicides in the United States involved a firearm. In addition to the thousands of single deaths, an uptick in mass shootings has brought attention to the issue of accessibility to weapons. With shootings at Virginia Tech (2007), Newtown (2012), Charleston (2015), Orlando (2016), San Bernardino (2017), Las Vegas (2017), and Parkland (2018), activists and experts on both sides of the gun debate push for new legislation at the state level in hopes of solving a crisis and preventing and protecting future would-be victims.

According to a count by the San Francisco-based Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, more than 160 laws restricting gun use or ownership were passed in 42 states and the District of Columbia after the Newtown massacre.

These included broadening the legal definition of assault weapons, banning sales of magazines that hold more than seven rounds of ammunition, and increasing the number of potentially dangerous people on the no-purchase list. By another expert’s estimate, as G. M. Filisko reports in the American Bar Association Journal, about nine states have approved more restrictive laws, and about 30 have passed more pro-Second Amendment legislation. Pro-Second Amendment laws include widening open-carry and increasing the number of states that have reciprocity in respecting out-of-state permits. In 2009, only two states had permit-less carry. In 2017, North Dakota became the twelfth state to pass an open-carry law, sometimes called “constitutional carry” by its advocates.

After a mass shooting, the number of state firearms bills introduced increases. The types of laws passed depend on the party in power. Republican pro-Second Amendment civil liberties bills increased more permissive laws by 75 percent in states where Republicans dominate. In Democrat-controlled states researchers found no significant increase in new restrictive laws enacted.

Since the Las Vegas shooting in 2017, which resulted in a record number of deaths for a modern-day shooting, many people have focused on banning bump stocks, a device that essentially turns a semiautomatic rifle into an automatic one. New policies on both sides of the gun argument will continue to come and go with public concern over the issue, as legislatures design and pass them, and as courts determine whether they infringe on citizens’ civil liberties.