Economic Concepts

scarcity & choice

opportunity cost

cost/benefit analysis

Incentives & Behavior

monetary incentives

non-monetary incentives

Types of Economics

macro-economics

micro-economics

Imagine your teacher assigns you homework, but there’s a catch: it’s not worth any points. Would you complete it? For many students, the answer might be “probably not.” After all, if there’s no tangible reward, what’s the incentive? Now, consider this twist: the teacher explains that the homework is practice for a quiz the next day, and the quiz questions will closely mirror the assignment. Suddenly, completing the homework feels more important. The incentive has shifted—from earning points to being prepared for an assessment that could affect your grade.

But what if the story becomes more complex? That same night, you have a stack of assignments from other classes, all graded and due tomorrow with no extensions. Faced with limited time and competing priorities, the ungraded homework drops further down your to-do list. Here, scarcity—this time of time—forces you to make trade-offs, choosing to focus on the assignments that directly impact your grades. The ungraded homework, despite its potential value for the quiz, may not make the cut.

Now let’s change the scenario again. The assignment is to read a chapter from a novel for English class. It’s still not worth any points, but you happen to love the book. In this case, the incentive shifts once more. Points don’t matter because the activity itself—reading a story you enjoy—feels rewarding enough. This example shows that while incentives often drive behavior, they aren’t one-size-fits-all. Some actions are motivated by grades, others by practicality, and sometimes, simply by intrinsic enjoyment.

This small, everyday scenario illustrates a cornerstone of economics: the choices we make are influenced by the interplay of incentives, scarcity, and personal preferences. Understanding these dynamics helps explain not just individual decisions but also broader trends in society, from why people save money to how businesses set prices.

Economic Principles

Economics begins with a fundamental truth: resources are limited, but human wants are infinite. This reality, known as scarcity, forces us to make choices. Whether it’s time, money, or materials, we can’t have everything we want, so we must prioritize. Every choice we make—whether big or small—comes with trade-offs. For example, in the homework scenario, your time is a scarce resource. You might want to finish the ungraded homework, complete your other assignments, and still have time to relax, but you can’t do it all. You must choose how to allocate your time, which introduces the concept of opportunity cost.

Is it worth it? Opportunity Costs and the cost/benefit analysis

Opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative you give up when making a choice. If you decide to spend an hour on ungraded homework instead of studying for a graded quiz, the opportunity cost is the potential higher grade you could have earned by preparing more. On the other hand, if you prioritize studying for the quiz, the opportunity cost might be the clarity and confidence you would have gained from completing the homework. Opportunity cost highlights that every decision involves a sacrifice, even if it’s not immediately obvious.

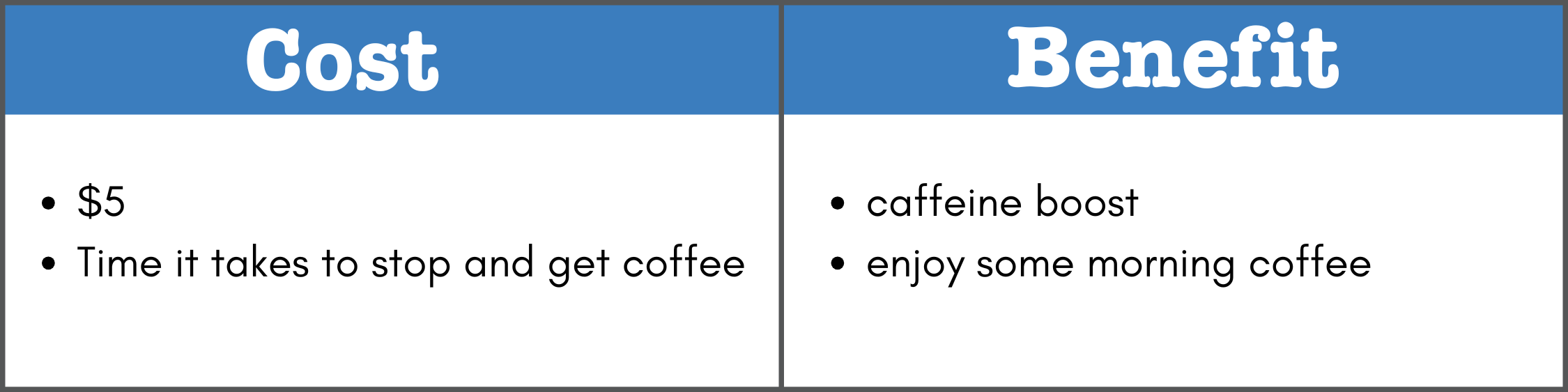

To navigate these decisions, people often rely on cost/benefit analysis—weighing the potential benefits of an action against its costs. In the homework example, you might ask: Is the benefit of doing the ungraded homework (being prepared for the quiz) worth the cost of time you could spend on other assignments or resting? If the teacher emphasized that the quiz questions would closely mirror the homework, the benefits might outweigh the costs. However, if the homework feels repetitive or the quiz is easy, you might decide the time would be better spent elsewhere.

Cost/benefit analysis also applies beyond academics. Imagine deciding whether to buy a $5 coffee on your way to school. The cost is $5, but the benefit might be the energy boost that helps you focus through the morning. If you only have $10 to last the week, that $5 coffee might not seem worth it, as the opportunity cost could be skipping lunch later. In both cases, you’re analyzing whether what you gain is worth what you give up.

These concepts—scarcity, opportunity cost, and cost/benefit analysis—help explain not only individual behavior but also larger economic decisions. A government might have to choose between funding education or healthcare, understanding that each choice comes with trade-offs. Businesses face similar dilemmas, deciding whether to invest in new technology or expand their workforce. In every case, the principles of economics provide a framework for understanding how to make choices in a world of limits.

Incentives Drive Behavior & Choices

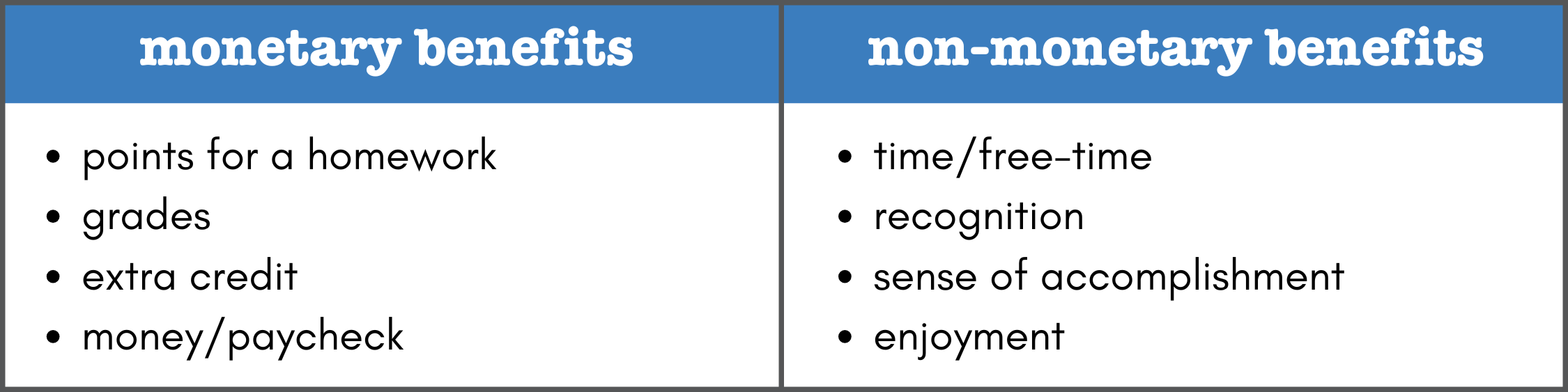

Incentives are the forces that motivate people to make certain choices, and they can broadly be divided into monetary incentives and non-monetary incentives. Both play a critical role in shaping behavior, and understanding their influence helps explain why people act the way they do, whether in personal decisions or large-scale economic trends.

Monetary incentives are rewards or penalties that involve money or other material benefits. For example, earning a paycheck motivates employees to show up for work, while a discount on a product encourages consumers to buy it. In the context of the homework anecdote, monetary incentives might not seem immediately relevant, but consider this: if the school implemented a policy that awarded small scholarships or gift cards for completing all assignments, students might be more inclined to do even the ungraded homework. The tangible reward of money or resources provides a clear reason to invest time and effort.

Monetary incentives often influence choices in the marketplace. For instance, a store offering “buy one, get one free” promotions motivates customers to purchase items they might not have otherwise considered. On a larger scale, governments use monetary incentives to shape behavior through policies like tax breaks for installing solar panels or fines for polluting. These incentives change the financial costs and benefits of certain actions, nudging individuals and businesses toward desired outcomes.

Non-monetary incentives, on the other hand, motivate behavior without directly involving money. These can include personal satisfaction, recognition, convenience, or social approval. Returning to the homework example, imagine you genuinely enjoy the subject or feel pride in being well-prepared for class. In this case, the motivation to complete the homework isn’t tied to grades (a more tangible “currency”) but to the intrinsic satisfaction of learning or the desire to impress your teacher or peers. Similarly, if the homework is reading a book you love, the joy of the activity itself becomes the incentive, making points or grades irrelevant.

Non-monetary incentives also play a significant role in broader economic and social contexts. Consider how people volunteer their time for charitable causes. Although there’s no monetary reward, they might be motivated by a sense of purpose, a desire to help others, or the recognition that comes with their contribution. Likewise, businesses often use non-monetary incentives to motivate employees, such as flexible work hours, awards, or opportunities for professional growth. These benefits, while not directly financial, can be just as powerful in influencing behavior.

Interestingly, monetary and non-monetary incentives often work together. For instance, a company might offer both a performance bonus (monetary) and public recognition (non-monetary) for outstanding work, appealing to both financial and emotional motivators. Non-monetary incentives, however, often include internal motivations as well. In the homework example, a student might complete the ungraded assignment not only to be better prepared for the quiz (a long-term benefit with academic consequences) but also because of the sense of accomplishment they feel after mastering the material, the intrinsic enjoyment they get from engaging with the subject matter, or the pride in knowing they are taking active steps to improve. For some, the feeling of making a difference—such as being the student who helps clarify difficult concepts for others during class—can also serve as a powerful motivator, showing how internal and external incentives can work hand in hand.

Understanding the balance between monetary and non-monetary incentives helps explain everything from individual choices to societal trends. Whether people are responding to a financial reward, a sense of accomplishment, or the joy of learning, incentives shape the decisions we make in profound and interconnected ways.

Types of Economics: Macroeconomics & Microeconomics

Economics is divided into two main branches: microeconomics and macroeconomics, each focusing on different levels of analysis. While both explore how scarcity and incentives shape decisions, their scope and perspective are distinct.

Microeconomics examines the behavior of individuals, households, and businesses in making decisions about limited resources. It focuses on small-scale interactions and specific markets, such as how consumers decide what to buy or how businesses determine what prices to charge. For example, microeconomics might analyze why a coffee shop raises prices during a busy morning rush or how a family chooses between spending money on groceries or dining out. It also delves into concepts like supply and demand, market structures, and the factors that influence individual decision-making.

Microeconomics often asks questions like:

- Why do gas prices fluctuate in different regions?

- How does a rise in wages affect a company’s hiring practices?

- What motivates a consumer to buy one product over another?

On the other hand, macroeconomics looks at the broader picture, studying the behavior and performance of entire economies. It focuses on large-scale economic factors such as national income, unemployment rates, inflation, and government policies. For instance, macroeconomics analyzes how a country’s central bank uses interest rates to control inflation or how global events, such as a pandemic, impact worldwide trade and economic growth.

Macroeconomics explores questions such as:

- What causes economic recessions and how can they be prevented?

- How do government spending and taxation policies affect national economies?

- Why do some countries experience rapid economic growth while others stagnate?

The distinction between microeconomics and macroeconomics lies not only in scale but also in focus. Microeconomics is concerned with the trees—individual agents and their decisions—while macroeconomics studies the forest, analyzing trends and forces that impact entire economies. However, the two fields are deeply interconnected. For example, the decisions of millions of individuals and businesses (studied in microeconomics) collectively shape the broader economic indicators and trends (studied in macroeconomics).

Understanding both microeconomics and macroeconomics provides a comprehensive view of how economic systems function, from the choices of a single shopper to the policies of a global government.